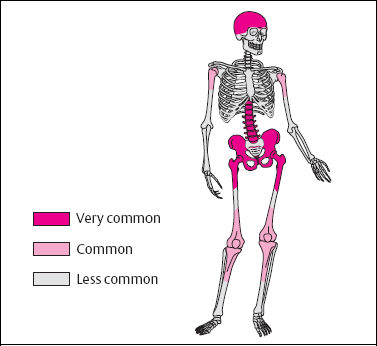

8 Various Bone and Soft-Tissue Disorders Synonym: Osteitis deformans. Paget disease has a prevalence for the axial skeleton (skull, spine, pelvis) and the femur and tibia (Fig. 8.1), but any bone can be involved. The involvement can be polyostotic, oligostotic or, less frequently, monostotic. Osteoporosis circumscripta corresponds to the lytic phase of Paget disease and is an early manifestation. The radiographic interpretation should address: In patients complaining of progressive pain, signs of – degeneration (especially to sarcoma or giant cell tumor) have to be looked for diligently. Therapy: Calcitonin, diphosphonate.

Paget Disease

The most widely accepted theory is that Paget disease is caused by a virus. According to this theory, the osteoclasts infected with the virus become activated after many years of ‘infection’ and thus cause rapid bone resorption. Compensatory activation of osteoblasts and fibroblasts induces reactive new bone production with the formation of a more primitive woven bone. Eventually, the bone production predominates, resulting in bone of increased volume and density. Lytic, mixed, and sclerotic stages of the condition are identified.

The most widely accepted theory is that Paget disease is caused by a virus. According to this theory, the osteoclasts infected with the virus become activated after many years of ‘infection’ and thus cause rapid bone resorption. Compensatory activation of osteoblasts and fibroblasts induces reactive new bone production with the formation of a more primitive woven bone. Eventually, the bone production predominates, resulting in bone of increased volume and density. Lytic, mixed, and sclerotic stages of the condition are identified.

With a prevalence of about 3% in patients older than 40 years of age, Paget disease is a common bone condition. However, in about 90% of cases it is asymptomatic and is discovered as an incidental finding. The condition becomes clinically apparent when bone pain develops, or if complications develop (Table 8.1). In the active stage, urine excretion of hydroxyproline (corresponding to osteoclast activity) and serum alkaline phosphatase (corresponding to osteoblast activity) are increased, and these values fall in the osteosclerotic stage.

With a prevalence of about 3% in patients older than 40 years of age, Paget disease is a common bone condition. However, in about 90% of cases it is asymptomatic and is discovered as an incidental finding. The condition becomes clinically apparent when bone pain develops, or if complications develop (Table 8.1). In the active stage, urine excretion of hydroxyproline (corresponding to osteoclast activity) and serum alkaline phosphatase (corresponding to osteoblast activity) are increased, and these values fall in the osteosclerotic stage.

| Lesion | Cause |

|---|---|

| Pathologic fractures | Statically inadequate bone Frequently involving the proximal tibia |

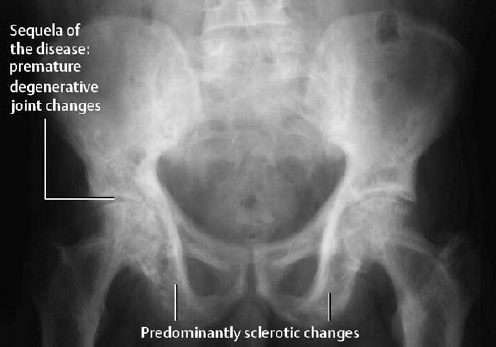

| Paget arthropathy | Premature degenerative changes most frequently in the hip and knee (Fig. 8.6) |

| Neurologic findings | Bony expansion with compression of cranial nerves, spinal canal or root compression |

| Neoplastic transformation | In less than 1% of cases. Usually osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma or giant cell tumor |

Strictly lytic or sclerotic stages of Paget disease are rarely observed. It is this coexistence of lytic and sclerotic changes seen in the mixed stage that enables the diagnosis of Paget disease.

Strictly lytic or sclerotic stages of Paget disease are rarely observed. It is this coexistence of lytic and sclerotic changes seen in the mixed stage that enables the diagnosis of Paget disease.

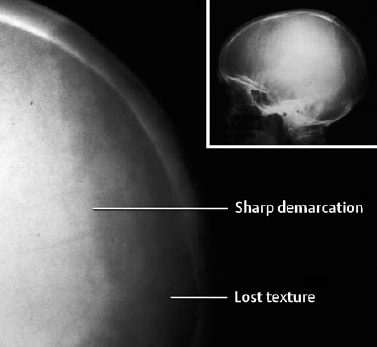

Lytic stage (Figs. 8.2, Figs. 8.7):

- loss of the trabecular texture,

- sharply demarcated, V-shaped or flame-shaped radiolucency (also referred to as ‘candle flame’ or ‘blade of grass’),

- subarticular onset with diaphyseal extension.

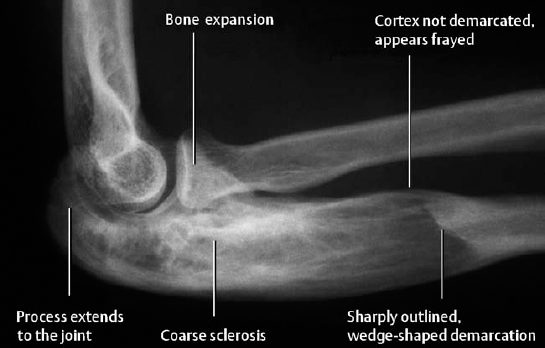

Mixed stage (Fig. 8.3, Fig. 8.5):

- coarse trabecular pattern,

- osseous expansion and deformity,

- thickened cortex with striations; ‘bubbly’ pattern in small bones

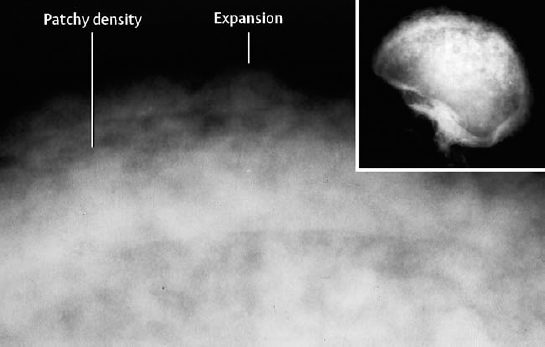

Sclerotic stage (Fig. 8.4):

- patchy or homogeneous thickening.

Assessment: Radiographs are generally adequate to diagnose and follow Paget disease.

Extensive osseous turnover with increased vascularity corresponds to massive uptake in areas involved with Paget disease. Bone scanning is suitable to determine the extent of pagetic involvement and also, in some cases, to differentiate Paget disease from metastases on the basis of its typical distribution pattern.

Extensive osseous turnover with increased vascularity corresponds to massive uptake in areas involved with Paget disease. Bone scanning is suitable to determine the extent of pagetic involvement and also, in some cases, to differentiate Paget disease from metastases on the basis of its typical distribution pattern.

Fig. 8.1 Preferred sites of Paget disease.

Fig. 8.2 Lytic state of Paget disease in the skull (osteoporosis circumscripta).

Fig. 8.3 Characteristic radiographic findings of the mixed stage of Paget disease.

Fig. 8.4 Sclerotic stage of Paget disease in the skull (‘cotton-wool’ appearance).

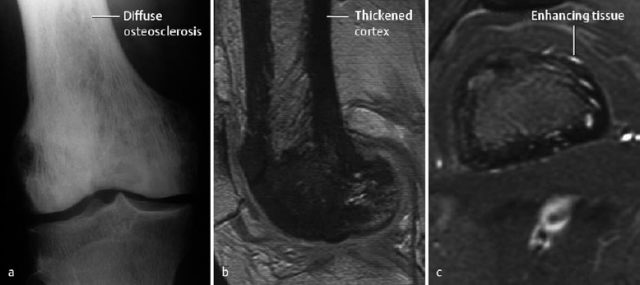

The cortex is thickened but also shows a permeative striated or granular pattern (Fig. 8.9b). The striated or granular areas show high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and enhance (Fig. 8.9c). The enhancing zones correspond to fibrovascular tissue. Furthermore, the fibrovascular tissue encroaches on the marrow, which is permeated with striated or granular fat marrow remnants.

The cortex is thickened but also shows a permeative striated or granular pattern (Fig. 8.9b). The striated or granular areas show high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and enhance (Fig. 8.9c). The enhancing zones correspond to fibrovascular tissue. Furthermore, the fibrovascular tissue encroaches on the marrow, which is permeated with striated or granular fat marrow remnants.

The typical presentation of Paget disease does not pose a diagnostic problem. Atypical presentation or the clinical context can raise differential diagnostic questions.

The typical presentation of Paget disease does not pose a diagnostic problem. Atypical presentation or the clinical context can raise differential diagnostic questions.

The criteria helpful in differentiating Paget disease from metastases are listed in Table 8.2

Sarcomatous transformation must be suspected if new lytic areas develop in areas of sclerotic bone and if parosseous soft-tissue extension develops. Soft-tissue widening or newly formed bone within the surrounding soft tissues is highly suspicious for tumor and must be further evaluated by biopsy. Suspicious clinical findings are pain and soft-tissue swelling. Aside from providing a more exact evaluation of tumorous soft-tissue infiltrations, CT and MRI enable differentiation of the tissues within osteolytic areas; Paget disease contains preserved fatty marrow, and tumorous destruction has to be suspected in cases of its complete absence.

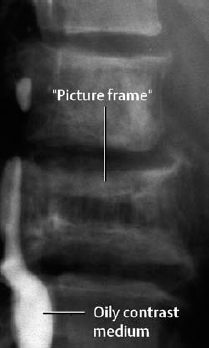

In the spine, increased AP diameter and framing of the affected vertebrae suggest Paget disease (Fig. 8.8). Inconclusive cases should be further evaluated by cross-sectional imaging.

Post-traumatic changes generally induce less pronounced enlargement of the bone, but the differentiation can be difficult in individual cases. The bone scan might support the diagnosis by showing additional areas with characteristic pagetic uptake.

| Paget disease | Metastases |

|---|---|

| Few lesions covering a large area (scintigraphy) | Multiple small lesions (scintigraphy) |

| Sharp demarcation | Indistinct demarcation |

| Coarse sclerosis | Often homogeneous, faint sclerosis |

| Epiphysis invariably involved (most frequent exception: tibia) | |

| Pelvis: often unilateral involvement | Pelvis: usually diffuse involvement |

| Enlarged bone |

Fig. 8.5 Mixed stage of Paget disease, targe lytic areas, primarily in the humeral head.

Fig. 8.6 Sclerotic manifestation of Paget disease in the pelvis with severe Paget arthropathy.

Fig. 8.7 Rare location of Paget disease in the distal tibia with coarse linear sclerosis (transition from lytic to mixed stage).

Fig. 8.8 Characteristic appearance of a pagetic vertebra with picture framing and osseous expansion (oily contrast medium is incidentally noted in the spinal canal).

Fig. 8.9 Paget disease of the distal femur (a). The T1-weighted GE sequence (b) clearly delineates the thickened and striated cortex. c Enhancement of the fibrovascular tissue after administration of contrast medium (Tl-weighted SE sequence with fat suppression).

Sarcoidosis

Synonym: Boeck disease.

Sarcoidosis can occur at any age, but has a definite predilection for the ages of 15 to 40 years. Osseous involvement is seen in about 5% and joint involvement in up to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis can occur at any age, but has a definite predilection for the ages of 15 to 40 years. Osseous involvement is seen in about 5% and joint involvement in up to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis.

Osseous sarcoidosis most commonly involves the hands (metacarpals and phalanges). Its clinical manifestation usually is confined to soft-tissue swelling of the affected areas. Articular sarcoidosis usually involves the wrist, ankle, knee, and elbow, as well as the minor joints of the hand. It causes transient, possibly recurrent bouts of arthralgia. Chronic involvement rarely causes persistent restriction of movements or deformities of the joints.

Radiographically detectable changes can be asymptomatic, and clinical findings might not correspond to radiographic changes. The radiographically detectable changes of osseous sarcoidosis can be placed into three groups:

Radiographically detectable changes can be asymptomatic, and clinical findings might not correspond to radiographic changes. The radiographically detectable changes of osseous sarcoidosis can be placed into three groups:

- Diffuse changes of the spongiosa and cortex.

These changes begin with osteopenia and progress to a lacelike trabecular pattern, as well as to Assuring and thinning of the cortex. The changes may resemble permeative destruction (Fig. 8.10).

- Cystic lesions.

These can be centrally located, characteristically in the epimetaphyseal region of the phalanges, and are surrounded by thin marginal sclerosis. Eccentrically located lesions cause marginal scalloping with bulging of the overlying cortex (Fig. 8.11). Rarely, acro-osteolysis can also occur in sarcoidosis (Fig. 8.12).

- Osteosclerosis.

In contrast to the aforementioned changes, which are primarily found in the metacarpals and phalanges of the hands, osteosclerosis tends to occur in the central skeleton (spine, pelvis, skull, ribs, and proximal ends of the long tubular bones). This pattern is rare, often occurs long after resolution of the pulmonary sarcoidosis, and is usually in a local or generalized patchy distribution. Acro-osteosclerosis can occur.

For articular sarcoidosis, the same criteria as those for acute and chronic synovial arthritis apply.

This is rarely indicated, except for cases requiring differentiation from osteoblastic metastasis (old sarcoidosis lesions show no increased uptake on the bone scan).

This is rarely indicated, except for cases requiring differentiation from osteoblastic metastasis (old sarcoidosis lesions show no increased uptake on the bone scan).

Sarcoidosis tends to be bilateral but asymmetrical. The important differential diagnoses of sarcoidosis are listed in Table 8.3. Especially for differentiating from malignancies (sarcoma, plasmocytoma, metastases, and others), it is important to remember that sarcoidosis almost never induces a periosteal reaction.

Sarcoidosis tends to be bilateral but asymmetrical. The important differential diagnoses of sarcoidosis are listed in Table 8.3. Especially for differentiating from malignancies (sarcoma, plasmocytoma, metastases, and others), it is important to remember that sarcoidosis almost never induces a periosteal reaction.

The best method for diagnosis of sarcoidosis is bronchoalveolar lavage with determination of the ratio of T4/T8 suppressor cells. The serum concentration of the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is simpler but is less specific.

|

|

| Morphology | Differential diagnoses | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Permeative bone destruction | Malignancy Osteomyelitis | Frequent periosteal reaction, history, age Frequent periosteal reaction, clinical findings, laboratory |

| Cystic changes | Bone cyst | Solitary, in contrast to sarcoidosis |

| Brown tumor | Laboratory | |

| Enchondroma | Periosteal reaction, cortical destruction (rare in sarcoidosis) | |

| Metastasis | Distribution pattern (scintigraphy), age | |

| Osteosclerosis, | Malignancy | Distribution pattern (scintigraphy), age |

| acro-osteosclerosis | Hematologic disease | Laboratory |

| Renal osteodystrophy | Laboratory | |

| Myelofibrosis | Involvement of other organs | |

| Paget disease |

Paget disease is a chronic condition, commonest in the elderly and characterized by enlarged, often deformed, coarsely trabeculated bone. The etiology of the condition has not been proven conclusively.

Paget disease is a chronic condition, commonest in the elderly and characterized by enlarged, often deformed, coarsely trabeculated bone. The etiology of the condition has not been proven conclusively.

CT rarely contributes to the diagnosis of Paget disease. However, it can be used to evaluate complications (nerve compression, malignant transformation) and to segregate it from other conditions.

CT rarely contributes to the diagnosis of Paget disease. However, it can be used to evaluate complications (nerve compression, malignant transformation) and to segregate it from other conditions.

Osteitis cystitis multiplex jüngling: polycystic type of bone sarcoidosis.

Osteitis cystitis multiplex jüngling: polycystic type of bone sarcoidosis.