Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Malfunction

Bryan M. Hoag

Daniel B. Nissman

CLINICAL HISTORY

80-year-old female presenting with gradual onset of mental status changes.

FINDINGS

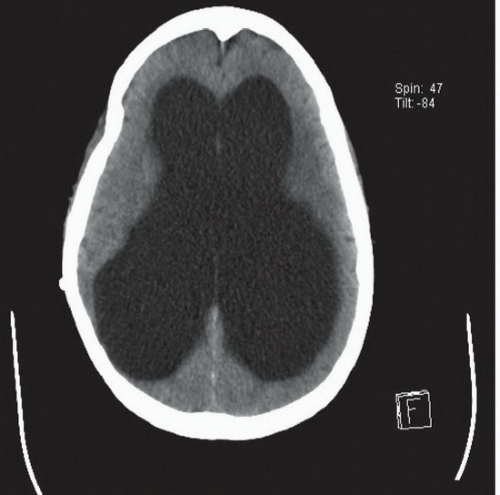

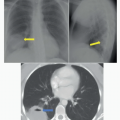

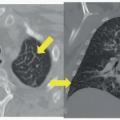

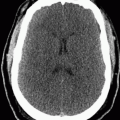

AP radiograph of the neck (Fig. 98A) demonstrates extensive calcification about the ventriculoperitoneal shunt tubing that overlies the right neck. A focal discontinuity is present where the tubing overlies the right lung apex (arrow). Axial CT image in brain window (Fig. 98B) reveals severe dilatation of the lateral ventricles.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hydrocephalus ex vacuo, ventriculoperitoneal shunt discontinuity, intact ventriculoperitoneal shunt with concretions.

DIAGNOSIS

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt discontinuity with hydrocephalus.

DISCUSSION

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are a highly effective treatment for hydrocephalus. Unfortunately, shunt malfunction is common, occurring in up to 40% of cases at 1 year and 70% of cases at 10 years.1 Clinical presentation in the setting of shunt failure is highly variable; headache, nausea, and vomiting are frequently reported, all of which can be attributed to elevated intracranial pressure. Delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to cranial nerve palsies, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, and coma.

Modern day ventriculoperitoneal shunts are composed of a proximal catheter, reservoir, valve regulator, and distal catheter. The reservoir is located in the subcutaneous tissues over the skull and feeds a one-way valve. The proximal catheter extends from the reservoir intracranially and typically terminates in the frontal horn of either lateral ventricle, while the distal catheter extends caudally through the subcutaneous tissues of the neck, anterior chest, and anterior abdomen, ultimately terminating in the peritoneal cavity. Mechanical complications, including shunt obstruction, disconnection, fracture, and migration, are the most common causes of shunt malfunction. Obstruction of the proximal shunt catheter is the most common cause of shunt malfunction in the first 2 years, often shortly after placement from postoperative debris and blood products. Other common causes of obstruction include shunt kinking, choroid plexus ingrowth at the proximal tip, and pseudocyst formation at the distal tip. Pseudocysts are loculated collections of CSF caused by peritoneal adhesions or covering of the catheter tip by the greater omentum. Shunt disconnection typically occurs soon after placement because of improper surgical technique or defective shunt components. Repeated mechanical stress can lead to shunt weakening and fracture, most often in the neck. Over time, dystrophic calcifications (sometimes called concretions) may develop around the shunt tubing, predisposing them to fracture. Additional complications include infection, ventricular loculations, overdrainage, and ascites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree