Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 68-year-old man who presented with back and leg pain. Patient has a history of two L1-L2 lumbar diskectomies. He did not have much improvement of his preoperative back and leg pain. The leg pain involved the right lower extremity. He has had progressive symptoms since. The pain originates in the right paraspinal area, in the mid to upper lumbar spine, and radiates to the buttock and anterolateral thigh. It does not go past the knee. The back pain is much worse than the buttock and leg pain and can reach 7 out of 10 on the pain scale. There is no left lower extremity pain. There is no numbness or weakness in the left upper and lower extremity.

Imaging Presentation

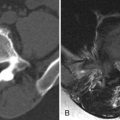

Axial T1-weighted image and fat-saturated, post-contrast, T1-weighted image reveal a rind of soft tissue along the ventral and right lateral aspect of the vertebral body that extends posteriorly to the lateral aspect of the pedicle in the region of the right lumbar trunk. Similar signal intensity is seen within the right ventral vertebral body. There is an osteophyte projecting from the right ventral vertebral body. The findings are thought to represent inflammation related to the osteophyte formation ( Fig. 79-1 ) .

Discussion

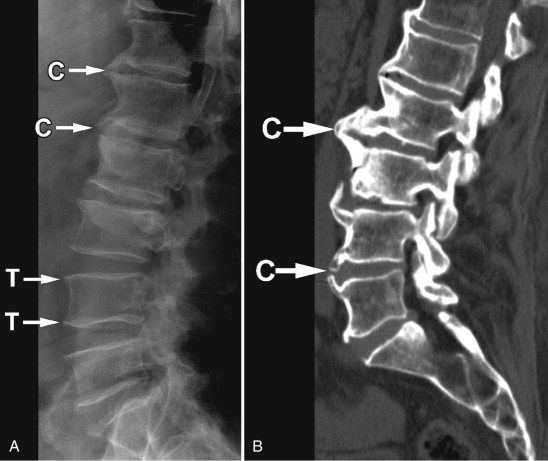

Vertebral osteophytes are a characteristic of disc degeneration. By definition, an osteophyte is an overgrowth of bone tissue. It is commonly referred to as a bone spur . Osteophytes can occur anywhere in the body, but they are most commonly found along the spine. As we age, the intervertebral discs become more desiccated and less compliant. The intervertebral disc acts as a cushion between a motion segment, preventing trauma to the adjacent vertebral bodies while allowing smooth movement in multiple directions. Degeneration of the annulus fibrosis of the disc renders it unable to withstand the stresses of axial loading, causing it to bulge outward. Over time, this bulging of the annulus on the vertebral edge leads to formation of an osteophyte at the osseous site of attachment to the annulus (Sharpey’s fibers). The osteophytes can be small and parallel to the endplate ( traction osteophyte ) or be larger, curved, and even bridging two adjacent vertebra ( claw osteophyte ) ( Fig. 79-2 ) . Some believe that claw osteophytes are a natural progression from traction osteophytes. They believe that traction osteophytes are the initial stage of an ossification process at an unstable level, and that their conversion to claw osteophytes indicates an attempt to increase stability by ossification of annular fibers.

Osteophytes are often found in the aging spine; however, there is an increased frequency of vertebral osteophytes in athletes and those involved with chronic heavy physical activity. Osteophytes are found in approximately 80% of men and 60% of women by age 50 and 95% in both genders by age 70. The study of lumbar osteophytes conducted by Shao and colleagues demonstrated that men had a greater prevalence of osteophytes when compared with women throughout all ages, although the gap narrows after the age of 70. The study also demonstrated that the most prevalent site for a lumbar osteophyte in men was at the L4 level and for women at the L3 level. A study of a population of South-African black and white people by Taitz demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of cervical osteophytosis in the black population of both genders as compared with the white population. Furthermore, in the white population, there was a combination of same level vertebral osteophyte and facet osteophyte as opposed to the black population that demonstrated osteophyte formation at either the vertebral level or facet level. The white population also demonstrated a greater degree of facet osteophytosis compared to the black population. The distribution of osteophytes within the spine is greatest at T9-10 and L3-4, which is intuitive because these levels are at or near the sites of maximum sagittal thoracic and lumbar curvature. Many studies show positive correlation between intervertebral disc degeneration and osteophyte formation with heavy activity. Other studies show obesity as a risk factor for osteophyte formation because of the mechanical factors involved in the additional stress on the skeletal system.

It is traditionally thought that osteophytes are not painful themselves, but can cause low back pain because of compression of the spinal canal, neural foramen, and/or lateral recess. Osteophytes, along with associated disc height loss, disc bulging, and facet joint degeneration, are frequently a contributing factor in neural foraminal narrowing, which may lead to radicular symptoms. Cervical vertebral osteophytes and disc degeneration as well as apophyseal joint osteoarthrosis can progress to involve the nerve root and cause neck and/or radicular pain, as can posterolateral osteophytes in the lumbar spine. A study by Matsumoto and colleagues reported several cases of patients with L5 radicular pain related to entrapment of the extraforaminal L5 nerve root between an L5 osteophyte and the sacral ala.

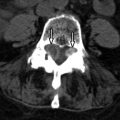

Recently, a hypothesis that painful stimuli could arise directly from an osteophyte has been proposed. Five patients were described with degenerative spine arthritis and large vertebral osteophytes. Each had undergone a traditional therapeutic regimen of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral narcotics, epidural and facet injections, and physical therapy that did not result in any significant pain relief. All five patients received percutaneous injections of anesthetic and steroid around the margin of the osteophyte ( Fig. 79-3 ) , and all patients had postinjection pain scores that decreased by 50% or more. All patients had return of their pain, with some patients having relief for 3 to 4 months. There is likely an inflammatory component with some vertebral osteophytes. It may be that an inflammatory reaction occurs around a vertebral osteophyte as it grows/enlarges and that the inflammatory reaction quiesces when the osteophyte is dormant. It is well known that patients may have no pain in a region of severe foraminal narrowing, and yet others may have pain with very mild narrowing. Neural compression alone is not the only factor in the cause of pain. There is often an inflammatory reaction that envelops or is adjacent to the spinal nerve root or its branches that is the immediate cause of the pain and is what is being treated with steroid injections (see Fig. 79-1 ). This type of pain generation may be similar to what one sees with inflammatory facet joint arthopathy (facet synovitis).