CHAPTER 7 Videofluoroscopy

Introduction

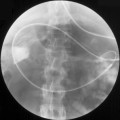

Videofluoroscopy of swallow (VFS) is defined by the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) (2006) as a modification of the standard barium swallow examination used in the assessment and management of oropharyngeal swallowing disorders. This instrumental swallowing evaluation is often described as the ‘gold standard’ for the assessment of dysphagia (Daniels et al., 1997; Robbins et al., 1999). Dysphagia is defined as a disorder of swallowing food (solid and/or liquid) from the mouth to the stomach (Logemann, 1998). Swallowing disorders can occur at every age and have various etiologies. Swallowing dysfunction can be caused by head and neck pathologies (e.g. inflammations and tumors of the oral cavity, oropharynx and larynx), neurological diseases and injuries (e.g. strokes, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease (MND), Parkinson’s disease, tumors and head injury) or other illnesses (e.g. psychological/functional, or as a side effect of medication). As stated by the RCSLT in their Policy Statement (2006), VFS can be used for assessment, treatment and management of swallowing where the suspected condition or disease process impacts upon swallow function and may result in a risk of death, pneumonia, dehydration, malnutrition and psychosocial issues related to discomfort and difficulty in eating and drinking.

Videofluoroscopy has the additional benefit of providing an objective baseline to which future examinations can be compared as a measure of improvement and enabling management strategies to be formulated. Martino et al. (2000) reinforced the importance of videofluoroscopy by stating that the validity of most other assessments and screening tools is often measured against videofluoroscopy and none comes close to VFS in terms of sensitivity and specificity. This chapter will provide the basis to enable a greater understanding of the videofluoroscopic procedure and the predisposing factors necessary to create a successful fluoroscopy team.

Purpose and benefits

Being both a time consuming and costly examination, it is vital that the actual VFS procedure runs as smoothly as possible. Communicating the plans of the procedure to all staff involved and prior explanation to the patient/carer will ensure minimal time delay. This should in turn prevent the patient and staff feeling rushed and anxious, both of which may result in a suboptimal examination. Patients must be fully informed about the VFS procedure prior to the examination. Consideration should be given to providing information in accessible spoken, written and/or visual formats, including the nature, purpose and likely effects of the examination (RSCLT 2006). Logemann (1998) categorically states that:

Also known as a modified barium swallow, a VFS is simply that – an adjustment to the traditional barium swallow. One modification is that low density contrast is utilized which highlights flow through the oropharynx much better than high density used in traditional barium swallows (where increased coating of the mucosal wall is desired). Further modifications are associated with the volumes and consistencies of the contrast agents provided, together with the speed at which they are given, attempting to replicate the consistencies of everyday food and fluid. This then demonstrates any dysfunction of oropharyngeal deglutition, enabling treatment and therapy aims to be devised. The primary aims of the VFS as described by the RCSLT (2006) are seen in Box 7.1.

BOX 7.1 Purpose of videofluoroscopy as defined by RCSLT (2006)

Evaluation of swallowing physiology, including lip and tongue function, velopharyngeal closure, base of tongue retraction, hyolaryngeal elevation, pharyngeal contraction, upper esophageal sphincter function and airway protection mechanisms

Evaluation of swallowing physiology, including lip and tongue function, velopharyngeal closure, base of tongue retraction, hyolaryngeal elevation, pharyngeal contraction, upper esophageal sphincter function and airway protection mechanisms Biofeedback. This involves the correlation of videofluoroscopy and intraluminal manometry, in addition to taught techniques of safer swallowing for volitional augmentation in order to modify impaired swallowing

Biofeedback. This involves the correlation of videofluoroscopy and intraluminal manometry, in addition to taught techniques of safer swallowing for volitional augmentation in order to modify impaired swallowingAs is stated by RCSLT (2006): ‘Patients must undergo an appropriate clinical assessment of swallowing by a Speech and Language Therapist (SLT) prior to VFS being undertaken’. The widely accepted standard procedure is for all patients to undergo a clinical swallowing evaluation (CSE) prior to completion of VFS. This will serve to fulfil many purposes, inclusive of enabling the aims of VFS to be established; assessment of candidate suitability for VFS; full explanation of the procedure (inclusive of aims of outcome); and obtaining of consent.

In addition, RCSLT (2006) state that an SLT-led CSE prior to VFS will also ‘assist in determining the nature and severity of the swallowing disorder and other factors contributing to the conduct of the VFS, such as cognition, presence of the carer, feeding arrangements, positioning and anxiety etc.’ It will also aid communication within the VFS to alert the radiographer and other multidisciplinary team (MDT) members what the plans for the procedure are and how they are to be completed. Communication with the patient during the VFS is imperative so that they are aware of every step of the procedure. The pre-VFS CSE should have prepared them with instructions, but anxiety and confusion can compound any complications and, if not treated accordingly, can waste the examination completely by altering the results from those aimed to be achieved, e.g. positional modification. The patient should be instructed clearly and concisely, by demonstration if necessary. If they do not complete the desired instruction they may aspirate contrast to such an extent that the examination has to be abandoned. Potential dangers of aspiration such as choking and pneumonia are also factors which correct communication should avoid.

It must be noted that patients rarely present with an isolated dysphagia. As previously mentioned, dysphagia usually arises as a result of a wide range of pathologies, which often have other associated motor, sensory and emotional/psychological problems. These must all be taken into account when planning and arranging a VFS. A patient who is bedbound and unable to support themselves in an upright position may not be a suitable candidate for a VFS due to poor strength and/or restricted movement, but accommodating alterations to the procedure are possible. This includes specialist seating equipment, physical supports or simple altered position of the x-ray table. It must be noted that within a VFS the ideal initial position for examination is a lateral view but, for a bedbound patient who is only able to manage supine positioning, anterior-posterior (AP) viewing may be the only possibility. Within a fluoroscopy suite equipped with a C-arm, manipulation of the x-ray tube to the side of the patient will enable lateral viewing but, in the traditional screening room, this is not possible and viewing is limited to AP positioning. While this has benefits for assessment of laterality of deficit, full assessment of laryngeal penetration and aspiration is not as clear as in the lateral position.

While the VFS is, as previously mentioned, the ‘gold standard’ within swallowing assessment, these motor, sensory and emotional/psychological constraints often limit the procedure and, in some cases, inhibit the examination. Langmore et al. (1991) summarize those groups of patients where VFS cannot be utilized:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree