Inflammation activity

Degree of fibrosis

G

Portal and periportal areas

Intralobular

S

Degree of fibrosis

0

No inflammation

No inflammation

0

None

1

Portal inflammation

Degeneration as well as rare spots and focal necrosis

1

Extended portal fibrosis and confined periportal fibrosis and intralocular fibrosis

2

Mild PN

Degeneration, spots of focal necrosis, acidophilic bodies

2

Periportal fibrosis, formation of fibrous septum, and reserved lobular structure

3

Moderate PN

Degeneration, fusion necrosis, or appearance of BN

3

Fibrous septum and deranged lobular structure, no hepatocirrhosis

4

Serious PN

Wide range of BN involving multiple lobules (multiple lobular necrosis)

4

Early hepatocirrhosis

30.3.2.3 Liver Failure

Acute Liver Failure

A large quantity of hepatocytes is subject to nonrecurring necrosis, with the necrotic area being above two thirds of the hepatic parenchyma. Otherwise, a large quantity of hepatocytes is subject to submassive necrosis or bridging necrosis, with accompanying moderate degeneration of survival cells. Survival inability occurs in the cases with above two thirds area of necrosis. Otherwise, in the cases with survival of over 50 % hepatocytes, the hepatocytes can rapidly regenerate after the acute stage and recovery can be expected, although there are degeneration and dysfunction of hepatocytes. In the cases with diffuse microvesicular fatty degeneration, the prognosis is commonly poor.

Subacute Liver Failure

The hepatocytes are subject to both new and old submassive necrosis (diffuse necrosis of the area 3). The reticular fibers in the old necrotic area collapse, possibly with deposition of collagen fibers. The residual hepatocytes proliferate into masses, with bile duct hyperplasia in a large quantity and cholestasis.

Chronic and Acute Liver Failure

The pathologic changes are characterized by newly emerging hepatocytic necrosis in different degrees based on chronic liver disease.

Chronic Liver Failure

The pathological changes mainly include diffuse hepatic fibrosis and formation of abnormal nodules, accompanied with uneven distribution of hepatocytic necrosis.

30.3.2.4 Hepatocirrhosis

Active Hepatocirrhosis

Hepatocirrhosis occurs with accompanying obvious inflammation, including inflammation in fibrous septum, debris necrosis around the pseudolobules and inflammation in regenerative nodules.

Static Hepatocirrhosis

The boundaries of pseudolobules are well defined, with rare inflammatory cells in the septum and mild inflammation of the nodules.

30.3.2.5 Hepatocirrhotic Nodules

Cirrhotic nodule refers to hepatocytic nodule due to proliferation of hepatocytes and hyperplasia of the surrounding interstitium on the background of hepatocirrhosis. It is the damage reactions of normal liver tissues, including regenerative nodule (RN) and dysplastic nodule (DN).

RN is benign nodule formed by focal hepatocytic and interstitial hyperplasia, accompanied by fatty degeneration, cholestasis, bile pigment and hemosiderin depositions, and inflammatory cells in different quantities in fibrous septum. DN, a precancerous lesion, can be graded into low-grade dysplastic nodule (LGDN) and high-grade dysplastic nodule (HGDN) based on the degree of cell atypia. LGDN is a group of hepatocytes, in a diameter of about 1 cm and with abnormal cytoplasm and nuclei but no histological evidence of malignancy. The group of hepatocytes contains hyperplasic and atypic large cells, with no real envelopes, false glands, and obvious thick girder structures. The nodules sometimes are poorly defined, but are commonly well defined due to fibrous scar in surrounding cirrhotic tissues, with accompanying iron and copper deposits as well as fatty degeneration. HGDN refers to cytological and/or histological atypia of hepatocytes in the nodules, which are not sufficiently support hepatic carcinoma. HGDN contains small cell atypia and dysplasia and/or atypical structure with fiber boundaries, which was formerly known as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. Resembling to LGDN, well- or poorly defined nodules on the background of hepatocirrhosis have no real envelope, but with more clear nodular appearance than low DN. They are commonly larger than LGDN, with a diameter of 10–20 mm. Histologically, the nodules are more obviously atypic, with concurrent transparent cells or fatty degeneration, which can be hardly differentiated from early small hepatic carcinoma with poorly defined boundary. There are also increased density of cells, irregular liver trabecular structure, and unpaired arteries (Figs. 30.1, 30.2, 30.3, 30.4, 30.5, and 30.6).

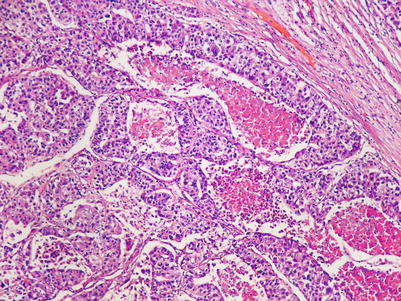

Fig. 30.1

Hepatocirrhotic nodules. (a) Formation of hepatocirrhotic nodules (H&E ×5). (b) Hepatocirrhotic nodules and their inferior envelope (H&E ×5)

Fig. 30.2

Atypic hyperplasia of hepatocytes. (a) Atypic hyperplasia of hepatocytes and hepatic cell hyperplasia (H&E ×20). (b) LGDN (H&E ×10)

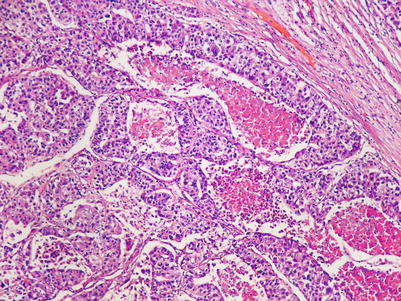

Fig. 30.3

Hepatocirrhotic nodules. (a, b) The liver gross specimen demonstrates multiple nodules on the liver surface in different sizes, surface congestion, or light yellowish color of some nodules and tough nodules in different sizes on liver section that are grayish white or light yellowish. (c) Microscopy demonstrates hepatocirrhotic nodules, HGDN with intact envelope (H&E ×5). (d) LGDN (H&E ×5). (e) Contrast of LGDN (left) and HGDN (right) (H&E ×5)

Fig. 30.4

HGDN, HCC. (a) Focal HCC in HGDN (H&E ×20). (b) CD34 are partially positive, and cancerous areas are positive (CD4 ×20). (c) GPC-3 is partially positive (GPC-3 ×20). (d) 5 % of Ki-67 is positive (Ki-67 ×20). (e) Focal breakage of the reticular fiber (reticular fiber ×20)

Fig. 30.5

HCC. (a) Low-grade differentiation level HCC (H&E ×10). (b) Obvious atypia of hepatic cancerous cells (H&E ×10)

Fig. 30.6

HCC. Cancerous tissues are adjacent to the normal tissues (H&E ×5) (Note: Figs. 30.1, 30.2, 30.3, 30.4, 30.5, and 30.6 are provided by Li HJ at Radiology Department, Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China)

RN is mainly nourished by the portal vein, with several hepatic arteries also providing nutrients to RN. From low-grade DN to HCC, the blood supplies from the portal vein gradually decrease, with firstly decreased arterial blood supply to following gradual increase of the blood supply due to tumor angiogenesis. The blood supply of the portal vein to the DN is basically normal or slightly decreased, with about 4 % of low-grade DN having increased arterial blood supply and about 17–32 % of high-grade DN having increased arterial blood supply. In small HCC with a diameter less than 2 cm, about 94 % of the cases have more arterial blood supply to the lesions than their surrounding hepatic tissues. The blood supply from the portal vein obviously decreases or disappears.

30.4 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

30.4.1 Incubation Period

The average incubation period of hepatitis A is 30 days, ranging from 5 to 45 days; while that of hepatitis B, 70 days ranging from 30 to 180 days; that of hepatitis C, 50 days ranging from 15 to 150 days; and hepatitis E, 40 days ranging from 10 to 70 days. And the incubation period of hepatitis D may be equivalent to that of HBV.

30.4.2 Clinical Manifestations of Various Types of Hepatitis

30.4.2.1 Acute Hepatitis

Acute Icterus Hepatitis

Acute jaundice hepatitis commonly occurs in the cases with HAV and HEV infections and can be occasionally found in the cases with HBV, HCV, and HDV infections. The whole course of the disease lasts for 1–4 months, with three distinct stages.

Pre-icterus Stage

The main symptoms include fever, fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, aversion to cooking oil, deep colored urine, and increased aminotransferase level by examination of the liver functions. This stage generally lasts for 5–7 days.

Icterus Stage

Jaundice of sclera and skin occurs, with hepatomegaly and tenderness; bilirubin, urobilinogen, and urobilin positive; and elevated levels of transaminase and serum bilirubin. This stage generally lasts for 2–6 weeks.

Convalescent Stage

The symptoms and jaundice disappear, with normal size of the liver and normal functions of the liver. This stage generally lasts for 1–2 months.

Acute Non-icterus Hepatitis

The onset is chronic, with no occurrence of jaundice during the course of disease. The other symptoms resemble to those in the pre-icterus stage of acute icterus hepatitis. As a mild hepatitis, it can occur in any type of hepatitis and tends to be misdiagnosed due to the absence of jaundice. However, its incidence rate is higher than acute icterus hepatitis, and, therefore, it is a more important source of infection than acute icterus hepatitis.

30.4.2.2 Chronic Hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis is commonly found in the cases with HBV, HCV, or HDV infection.

Mild Chronic Hepatitis

It was formerly known as chronic persistent hepatitis, with slight conditions and repeated occurrence of fatigue, poor appetite, aversion to cooking oil, upset of the hepatic region, hepatomegaly, tenderness, and possibly mild splenomegaly. In some cases, the symptoms and signs are absent. By the examination of the liver function, only 1–2 indicators show slight abnormality. The disease may persist for several years and may develop into moderate chronic hepatitis in only a minority of the cases.

Moderate Chronic Hepatitis

The symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests are between mild cases and severe cases.

Severe Chronic Hepatitis

There are obvious or persistent symptoms of hepatitis, such as fatigue, poor appetite, abdominal distension, and yellowish urine, with accompanying hepatic face, liver palms, spider angiomas, progressive splenomegaly, and persistent abnormality of the liver function. In addition to the abovementioned clinical manifestations, there are pathological changes of early cirrhosis by liver biopsy and clinical manifestations of cirrhosis in the clinical compensatory phase.

30.4.2.3 Severe Hepatitis (Liver Failure)

Severe hepatitis is the most serious type of viral hepatitis, accounting for 0.2–0.5 % of all viral hepatitis cases and with a high mortality rate. All the five types of viral hepatitis can develop into severe hepatitis. However, severe hepatitis caused by HAV and HEV infections is rare.

Acute Severe Hepatitis

It is also known as fulminant hepatitis and is commonly induced by fatigue, alcoholism, pregnancy, and medications that impair the liver or concurrent infection. Within 2 weeks after the onset, jaundice rapidly deepens in color, with rapidly decreased size of the liver, bleeding tendency, rapid increase of ascites, stinky liver, acute renal insufficiency (hepatonephric syndrome), and hepatic encephalopathy of different degrees.

Subacute Severe Hepatitis

It is also known as subacute hepatic necrosis. In 15 days to 24 weeks after the onset, the symptoms of extreme fatigue, poor appetite, frequent vomiting, and abdominal distention occur. There are also progressively deeper jaundice in color, daily increase of bilirubin level by at least 17.1 μmol/L or ten times as high as the normal level, above degree II of hepatic encephalopathy, obvious bleeding, significantly prolonged prothrombin time, and prothrombin activity being lower than 40 %. The cases with first occurrence of above degree II hepatic encephalopathy, including encephaledema and encephalopathy, are classified as the type of encephalopathy. The cases with first occurrence of ascites and its related symptoms, including pleural effusion, are classified as the type of ascites.

Chronic Severe Hepatitis

It is also known as subacute hepatic necrosis of chronic hepatitis, with the same clinical manifestations as those of subacute severe hepatitis.

30.4.2.4 Cholestatic Hepatitis

Cholestatic hepatitis, or cholangiolitic hepatitis, has an onset similar to that of acute icteric hepatitis, but the subjective symptoms are mild. The clinical manifestations include intrahepatic cholestasis, yellowish sclera and skin, itchy skin, lightly colored stools, hepatomegaly, and obviously elevated serum bilirubin by examination of the liver function that is mainly direct bilirubin. It can be hardly differentiated from extrahepatic obstructive jaundice. In rare cases, it may develop into biliary cirrhosis.

30.4.2.5 Hepatitis with Hepatic Cirrhosis

Typing Based on Inflammation

Based on the conditions of inflammation, hepatic cirrhosis is divided into two types: active type and static type.

Active Cirrhosis

It has manifestations of chronic hepatitis, such as fatigue, nausea, poor appetite, jaundice, accompanying abdominal wall varicosis, ascites, liver shrinkage and hardened liver, and splenomegaly. By examinations, aminotransferase is commonly found to be increased and albumin decreased.

Static Cirrhosis

No active manifestations of hepatitis can be found, with slight or nonspecific symptoms.

Typing Based on Liver Biopsy and Clinical Manifestations

According to pathology of the liver tissues and clinical manifestations, it can be divided into two types: compensatory type and decompensated type.

Compensatory Cirrhosis

It refers to early cirrhosis, with mild fatigue, poor appetite, and abdominal distention, but with no significant manifestations of liver failure. The patients may experience portal hypertension, such as mild esophageal venous varicosis but no ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Decompensated Cirrhosis

It refers to cirrhosis in the middle and advanced stages, with significant liver dysfunction and decompensated symptoms. The patients may experience ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, as well as portal hypertension-induced esophageal and gastric fundus veins varicosis or their rupture and hemorrhage.

30.4.2.6 Manifestations of Hepatitis in Special Populations

Children

Due to low-level immune response, children infected by hepatitis virus are commonly asymptomatic. Their infection of HBV tends to develop into asymptomatic carriers of HBsAg.

The Elderly

The incidence rate of hepatitis after hepatitis virus infection is lower than other age groups. However, the clinical manifestations are characterized by common occurrence of hepatitis E in the cases of acute hepatitis, high incidence rate of jaundice with deep coloration, persistence for a long period of time, more commonly found cholestasis type with common occurrence of complications, high percentage of severe hepatitis, and therefore a high mortality rate.

Pregnant Women

The symptoms are relatively serious after infection of hepatitis virus during pregnancy, especially in the late stage of pregnancy. The clinical manifestations are characterized by obvious gastrointestinal symptoms, common occurrence of postpartum massive hemorrhage, a high percentage of severe hepatitis, and therefore a high mortality rate. Hepatitis during pregnancy shows adverse effects on the fetus, with outcomes of preterm birth, stillbirth, and deformity.

30.5 Viral Hepatitis-Related Complications

30.5.1 Acute Hepatitis-Related Complications

Acute hepatitis-related complications are rare, which are commonly cholecystitis and cardiographic changes. Cholecystitis can be detected by ultrasound, commonly with no clinical manifestations. Cardiographic changes include transient changes of cardiac rhythm and T wave, which return to normal after hepatitis is cured. In addition, HBV- or HCV-related nephritis occasionally occurs. Acute hepatitis C commonly has autoimmune lesions.

30.5.2 Chronic Hepatitis-Related Complications

Chronic hepatitis may cause multiorgan lesions. The common complications of digestive system include biliary tract inflammation, pancreatitis, and gastroenteritis. The complications of endocrine system include diabetes mellitus. The common complications of hematological system include aplastic anemia and hemolytic anemia. The common complications of the circulatory system include myocarditis and polyarteritis nodosa. The common complications of the urinary system include glomerular nephritis and renal tubular acidosis. The common complications of skin include anaphylactic purpura. In addition, chronic viral hepatitis can develop into liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In China, hepatitis B is the most common cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, followed by hepatitis C.

30.5.3 Liver Failure-Related Complications

30.5.3.1 Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy can occur in the cases of any type of severe viral hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, especially in the patients with portosystemic shunt. The main manifestations include psychiatric and neurological symptoms in different degrees and the related signs. Based on the abnormalities of clinical symptoms, signs, and electroencephalogram, hepatic encephalopathy can be graded into 4°.

30.5.3.2 Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage is characterized by mucocutaneous hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding and even intracranial hemorrhage. Mucocutaneous hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding are more common and constitute important reasons for occurrence of death.

30.5.3.3 Hepatorenal Syndrome

The common manifestations include oliguria, anuria, azotemia, and electrolyte imbalance.

30.5.3.4 Secondary Infections

The common secondary infections include bacteremia, pneumonia, and peritonitis. The symptoms are usually atypical, with irregular fever and a mild increase of peripheral WBC count. Spontaneous peritonitis is more common, and only half of the patients experience abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness. Its positive rate is low by bacterial culture of ascitic fluid.

30.5.3.5 Other Complications

Other complications include electrolyte disorders and acid–base balance disorders, acute respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycemia, cardiovascular and hemodynamic abnormalities, encephaledema, encephalitis, and multiple organ failure.

30.6 Diagnostic Examinations

30.6.1 Laboratory Tests

30.6.1.1 Liver Function Test

Determination of Serum Enzymes

Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT)

ALT is the most commonly used indicator showing the hepatocytic functions in clinical practice. The enzyme is the most abundantly contained in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, which can be released out of the cells when the hepatocytes are damaged. In the cases with acute viral hepatitis, ALT significantly increases, which begins to decrease after occurrence of jaundice. In the cases of chronic viral hepatitis and cirrhosis, ALT can persistently or repeatedly increase. In patients with severe hepatitis, ALT may rapidly decrease with continuous increase of bilirubin, therefore showing up a phenomenon of biliary enzyme dissociation, indicating necrosis of hepatocytes in a large quantity.

Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST)

AST exists in the mitochondria with the same significance as AST but a lower specificity. In the cases of acute viral hepatitis, persistent high level of AST indicates its possible development into chronic.

Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP, AKP)

Its significant increase facilitates the diagnosis of extrahepatic obstructive jaundice. Serum ALP shows a significant increase in the patients with cholestatic hepatitis. The ALP level in children is significantly higher than that in adults, which is related to growth and development of the skeleton.

Glutamyl Transpeptidase (γ-GT)

Its diagnostic value is almost the same as ALP, but its level is not affected by diseases of the skeletal system. It can increase during the active stage of hepatitis, and it can significantly increase in the patients with liver cancer, bile duct obstruction, and drug-induced hepatitis.

Acetylcholine Esterase (CHE)

CHE is an indicator of liver reserve capacity, which decreases in the cases with obviously impaired liver functions. Its significant decrease commonly indicates poor prognosis.

Determination of Bilirubin

Serum bilirubin increases in patients with jaundice hepatitis, and it increases with slow regression to the normal level in patients with active liver cirrhosis. It also fades away slowly in active liver cirrhosis. The patients with severe hepatitis usually have a total serum bilirubin level of above 171 μmol/L. The increase of serum bilirubin is commonly related to the degree of hepatocyte necrosis.

Determination of Serum Protein

In the cases with acute hepatitis, the serum albumin can be within the normal range due to comparatively long half-life of albumin and the compensatory functions of the liver. In the cases of moderate or severe chronic hepatitis, hepatocirrhosis, and severe hepatitis, the concentration of serum albumin decreases due to dysfunctional synthesis of serum albumin by the liver.

Determination of Prothrombin Time

Prothrombin is primarily synthetized in the liver, and its level is positively related to the severity of liver damage. The prothrombin time activity (PTA) level being lower than 40 % or the prothrombin time being twice as long as that in the normal control indicates serious liver damage. PTA is also the most sensitive laboratory indicator predicting the prognosis of severe hepatitis.

Determination of Blood Ammonia Concentration

In the cases of liver failure, the ability for clearing ammonia decreases or is lost to cause an increase of blood ammonia, which is common in patients with severe hepatitis or hepatic encephalopathy.

Indicators of Hepatic Fibrosis

The major serological indicators of hepatic fibrosis include hyaluronic acid (HA), procollagen III (PC-III), collagen-IV (IV-C), and laminin (LN). HA is relatively sensitive in assessing hepatic fibrosis or liver cirrhosis. LN demonstrates the progress and severity of liver fibrosis and significantly increases in the cases of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and primary liver cancer. PC-III and IV-C are closely related to the activities of liver fibrosis but with no specificity. A continuous increase of PC-III in the patients with chronic hepatitis indicates possible deterioration of the conditions and development into liver cirrhosis. When the increased PC-III returns to the normal level, relieved conditions can be expected.

30.6.1.2 Detection of Hepatitis Virus Markers

Hepatitis A

Currently, the most reliable examination for the diagnosis of hepatitis A is to detect serum anti-HAV IgM. For the patients in the acute stage, it can be detected positive within 1 week after the onset. After its persistence for several weeks, its titer begins to decrease and turns negative after 3–6 months. It is a serological indicator for the early diagnosis of HAV infection. The serum anti-HAV IgG is positive in the convalescence of hepatitis, which peaks after 2–3 months and persists for several years or lifelong. It is a protective antibody. Therefore, anti-HAV IgM positive indicates current HAV infection, while anti-HAV IgM negative and anti-HAV IgG positive indicate a past history of HAV infection.

Hepatitis B

HBsAg and Anti-HBs

HBsAg can be positive in 2 weeks after HBV infection, indicating current HBV infection, but HBsAg negative cannot exclude HBV infection because of the existence of S-gene mutants. Anti-HBs is a protective antibody, whose positive indicates immunity to HBV and can be found in the convalescent stage of hepatitis B, in individuals with a past history of hepatitis B, and in vaccinated individuals. And anti-HBs negative indicates susceptibility to HBV infection, and vaccination is commonly recommended to these individuals. After HBV infection, concurrent HBsAg and anti-HBs negative may be found, indicating the window period. During this period, HBsAg is absent but anti-HBs has not been produced.

HBsAg and Anti-HBe

In the cases of acute HBV infection, the emergence of HBeAg lags behind that of HBsAg for a short period of time. Persistent HBeAg positive indicates active replication of HBV. Such patients have a strong infectivity and the conditions may develop into chronic. Persistent anti-HBe positive indicates a low level of HBV replication and a possibility of integrated HBV DNA into the host DNA for a long period of incubation. However, in some patients, HBeAg cannot be produced due to pre-C gene mutation.

HBcAg and Anti-HBc

HBcAg mainly exists in the core of Dane particles and cannot be detected by conventional examinations. HBcAg positive indicates the existence of Dane particles in serum and replication of HBV. Such patients have infectivity. Anti-HBc IgM can be detected in 1 week after the onset, and its high titer indicates active replication of HBV, while its low titer may indicate false positive. Anti-HBc IgG can persistently exist in serum. Only anti-HBc IgG positive indicates a past history of infection or a low level of current infection.

HBV DNA

HBV DNA is a direct indicator of virus replication and infectivity, which is commonly detected by dot blot hybridization or PCR. Quantitative HBV DNA has significance in assessing the virus replication, infectivity, and the therapeutic efficacy of antiviral therapies.

HBV Markers in Tissues

Immunohistochemistry can be applied to detect HBsAg or HBcAg in the liver tissues. And in situ hybridization or in situ PCR can be applied to detect HBV DNA in tissues. The findings facilitate to assess the curative effectiveness of antiviral medications.

Hepatitis C

Anti-HCV IgM and IgG are not protective antibodies but markers of HCV infection. Anti-HCV IgM can be detected immediately after the onset, which persists commonly for 1–3 months. The persistent anti-HCV IgM positive indicates continuous viral replication and likelihood of developing into chronic. Anti-HCV IgG can be detected in a long period of time. HCV RNA is in an extremely small quantity in serum, which can be detected by RT-PCR. HCV RNA can be detected in the blood in 1–2 weeks after HCV infection, which rapidly disappears after hepatitis C is cured.

Hepatitis D

HDVAg and Anti-HDV

In the early stages of HDV, HDVAg blood disease commonly occurs. The detection of serum HDVAg by ELISA or RIA facilitates the early diagnosis. Serum anti-HDV IgM appears early in the cases of acute HDV infection, which generally persists for 2–20 weeks and whose detection can also be applied for the early diagnosis. In the cases of chronic HDV infection, the serum anti-HDV IgM is in persistent high titer, and, therefore, persistently high titer of anti-HDV IgG is the main serological marker for identification of chronic HDV. In the cases with concurrent HBV and HDV infections, both anti-HBc IgM and anti-HDV are positive. In the cases of overlapping HBV and HDV infections, anti-HBc IgM is commonly negative and anti-HDV positive.

HDV RNA

Serum HDV RNA can be detected by cDNA probe spot hybridization. HDV RNA in the liver tissues can be detected by in situ hybridization or blot hybridization. The positive findings are the direct evidence supporting replication of HDV.

Hepatitis E

The anti-HEV IgG commonly persists for no more than 1 year. Therefore, both anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG can be the markers of recent HEV infection. PT-PCR has been applied to successfully detect HEV RNA in feces but has not been routinely applied in clinical practice.

30.6.1.3 Liver Biopsy

The specimens for liver biopsy should be subject to consecutive sections. In the cases of acute hepatitis, the findings are mainly inflammation, degeneration, and necrosis. In addition to inflammation and necrosis, the cases of chronic hepatitis have fibrosis of different degrees that may even develop into liver cirrhosis. The liver biopsy can accurately assess the conditions of chronic hepatitis and predict the prognosis of chronic hepatitis. Meanwhile, in situ hybridization and in situ PCR can be applied to define the status of pathogens and viral replications.

30.6.1.4 Alphafetoprotein (AFP)

The detection of AFP level is a routine examination for early diagnosis of HCC. During active hepatitis and hepatocytic repair, AFP increases in varying degrees, which should be dynamically observed. An increase of AFP level in the cases of acute severe hepatitis indicates hepatocytic regeneration, which facilitates to predict the prognosis.

30.6.1.5 Other Tests

Routine Blood Tests

In the early stage of acute hepatitis, the WBC count remains normal or slightly increases. During the icteric stage, WBC count decreases but lymphocytes relatively increases, with occasional findings of atypic lymphocytes. In the cases of cirrhosis with accompanying hypersplenism, decreases of erythrocytes, leukocytes, and thrombocytes can be found.

Routine Urine Tests

Determination of urine bilirubin and urobilinogen is a simple and effective way for early detection of hepatitis and facilitates its differential diagnosis from jaundice. In the cases of hepatocytic jaundice, both urine bilirubin and urobilinogen are positive. In the cases of hemolytic jaundice, urobilinogen level outweighs, while urine bilirubin outweighs in the cases of obstructive jaundice. In patients with deep jaundice or fever, the urine test witnesses the presence of protein, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and casts.

30.6.2 Diagnostic Imaging

30.6.2.1 Ultrasound

Ultrasound can be applied to dynamically observe the shape and size of the liver and spleen, their vascular distribution, the shape and size of the gallbladder, the thickness of the gallbladder wall, and the presence of ascites and liver cirrhosis. Ultrasound can also demonstrate hepatic portal and retroperitoneal lymphadenectasis and facilitate to exclude the occurrence of neoplasms.

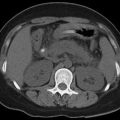

30.6.2.2 CT Scanning

The demonstrations of viral hepatitis by CT scanning are nonspecific, and, therefore, CT scanning is not applied for the diagnosis of viral hepatitis. However, studies have demonstrated halo sign around the intrahepatic vessels, bile duct system changes, and abdominal lymphadenectasis by CT scanning, which are related to severity of the conditions. Therefore, contrast CT scanning, somehow, demonstrates severity and prognosis of viral hepatitis.

In addition, CT scanning has important diagnostic value for viral hepatitis-related complications.

30.6.2.3 MR Imaging

MR imaging can be performed to detect liver cirrhosis and ascites as well as to exclude neoplasms.

30.6.2.4 PET/CT

PET/CT is generally not applied for the diagnosis of viral hepatitis.

30.7 Imaging Demonstrations

30.7.1 Imaging Demonstrations of Viral Hepatitis

30.7.1.1 Acute Viral Hepatitis

Ultrasound

The ultrasound demonstrations include slightly enlarged liver volume and generally increased liver echo, density, and roughness, with even distribution (Fig. 30.7). Based on the detailed ultrasound demonstrations, viral hepatitis can be divided into three types: mild, moderate, and severe hepatitis. (1) Mild hepatitis is demonstrated to have basically normal density of light spot from the liver parenchyma, slightly increased and more echoes in a shape of double small pipes or a small equality sign. (2) Moderate and severe hepatitis are demonstrated to have decreased density of light spots from the liver parenchyma as well as increased and more echoes from the wall of the portal vein, which occurs in proximal, middle, and distal portal vein.

Case Study 1

A male patient aged 60 years suffered from hepatitis C for 6 months.

Fig. 30.7

Acute viral hepatitis. (a–f) Ultrasound demonstrates more echoes from the liver and clearly defined course of the hepatic vein

Acute viral hepatitis can be accompanied by thickened gallbladder wall that is mostly bilateral, poor filling the gallbladder, shrinkage of the gallbladder, as well as abnormal stasis of echo spots in the gallbladder lumen that filled in the gallbladder lumen with consolidation manifestations. The specific demonstrations of the gallbladder can be found in the early stage of viral hepatitis. Along with the improved condition of hepatitis, the gallbladder wall commonly recovers, with decreased thickness of the gallbladder wall, absent lamination, normal volume, and absent echo within the bile.

The spleen is subject to slight enlargement, which returns to normal along with the improved conditions. Enlarged lymph nodes may be found in the portal area.

CT Scanning

Diffusive hepatomegaly and normal proportion of each hepatic lobes are demonstrated by CT scanning, which are resulted from inflammatory edema and congestion of the liver tissues.

Plain CT scanning demonstrates diffusive decrease of liver parenchyma density, which is lower than 42 Hu or the density of spleen, with even or uneven density. The changes contribute to density decrease including inflammatory edema and congestion of the liver tissue, hepatocytic swelling and necrosis, and fatty degeneration and abnormal blood perfusion. In the cases of acute severe hepatitis, the hepatic density is obviously uneven, with multiple flakes of low-density shadows with poorly defined boundaries and unfixed location. The shadows and normal hepatic parenchyma intersect to form map-like changes.

CT scanning also demonstrates enlarged and more abdominal lymph nodes, which mainly distribute in the portacaval space and liver hilum and around duodenal ligaments and around the abdominal aorta.

Pleural effusion is also demonstrated by CT scanning, in different quantities, and mainly distributes in the perihepatic and perisplenic areas as well as in the omental bursa and bilateral paracolic sulci.

The other CT scanning demonstrations include moderate enlargement of the spleen, slightly dilated intrahepatic bile duct, possible enlargement of the gallbladder with a long diameter of above 5 cm, and edema of the gallbladder wall. There are poorly defined boundaries between gallbladder wall and gallbladder fossa with surrounding liver tissue or presence of low-density ring.

By contrast CT scanning, no obviously abnormal enhancement of the liver parenchyma can be found in the arterial phase, obvious enhancement of liver periphery in the venous phase, and weak medial enhancement. Otherwise, uneven enhancement with lobar distribution can be found, with slow enhancement, even enhancement in the equilibrium phase, but weak enhancement of the whole liver (Fig. 30.8).

Case Study 2

A female patient aged 28 years

Fig. 30.8

Acute viral hepatitis and pleural effusion. (a–c) Plain CT scanning demonstrates enlarged liver and unevenly decreased density of the liver. Contrast CT scanning demonstrates uneven enhancement of the liver, perisplenic effusion in a small quantity, edema of the gallbladder wall, and pleural effusion in a small quantity

MR Imaging

MR imaging demonstrates enlarged liver volume, diffuse slightly long T1 slightly long T2 signals of the liver parenchyma due to inflammatory edema, with poorly defined boundaries and even signals. In the cases of acute severe hepatitis, MR imaging demonstrates obviously uneven signals and multiple scattering patches of long T1 long T2 signal shadows, indicating necrosis of liver parenchyma (Fig. 30.9).

Case Study 3

A male patient aged 57 years was diagnosed with severe jaundice.

Fig. 30.9

Acute viral hepatitis and ascites. (a, b) MRI T2WI demonstrates enlarged liver volume, uneven signal, flakes of slightly high signal, edema around intrahepatic portal system, and effusion around the liver and spleen

30.7.1.2 Chronic Viral Hepatitis

Ultrasound

Mild chronic viral hepatitis can be demonstrated with normal size of the liver and spleen or slightly enlarged liver, more intrahepatic echoes, and clearly defined running course of the hepatic vein.

Moderate chronic viral hepatitis can be demonstrated with slightly enlarged liver and spleen, more intrahepatic echoes that are unevenly distributed, clearly defined running course of the hepatic vein, and no widened lumen diameter of the hepatic and splenic veins (Fig. 30.10). CDFI demonstrates decreased velocity of portal blood flow.

Severe chronic viral hepatitis can be demonstrated with unsmooth liver surface with dull margins, obviously coarse intrahepatic echoes with uneven distribution, poorly defined running course of the hepatic vein, or slight stenosis and twists of the hepatic vein. There are also widened lumen diameter of the portal and splenic veins, with the lumen diameter of the portal vein being above 1.2 cm and the splenic vein being above 0.8 cm. In addition, enlarged spleen with a thickness of above 4.5 cm can be found, with bilateral sign of the gallbladder. CDFI demonstrates decreased velocity of the portal blood flow.

Case Study 4

A male patient aged 43 years experienced hepatitis B for 2 years.

Fig. 30.10

Chronic viral hepatitis and pelvic effusion. (a–c) Ultrasound demonstrates a plump liver with increased liver volume and smooth envelope, multiple low echoes of consolidation nodules from the liver parenchyma, lumen diameter of the hepatic portal vein trunk being 12 mm, accessory spleen, and pelvic effusion

CT Scanning

By CT scanning, the liver can be normal or slightly enlarged in size. Along with progress of the conditions, the volume of the right liver lobe can gradually shrink with appropriate proportion of all liver lobes or slightly increased proportion of the left liver lobe. The liver surface is not smooth, with slightly dull liver margin. The liver density unevenly decreases, being close to the spleen, which can be complicated by fatty liver. By contrast CT scanning, there are obviously uneven enhancement of the liver parenchyma and diffuse spots of low-density shadows. In the delayed phase, the enhancement and the spots are more obvious. The spleen is moderately enlarged, which is progressive. The portal vein is commonly poorly defined, with rare findings of dilated portal vein and its branches. Contrast CT scanning demonstrates low-density shadows around the portal vein, namely, halo sign around intrahepatic vessels (Fig. 30.11). There are commonly enlarged gallbladder, thickened gallbladder wall, and cholecystolithiasis. Enlarged and more abdominal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes can also be found. Sometimes, secondary changes occur including pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and pleural thickening. In the advanced stage, liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension occur.

Fig. 30.11

Chronic viral hepatitis and ascites. Contrast CT scanning demonstrates halo sign around intrahepatic vessels. The periphery of the liver and spleen is surrounded by liquid density shadows

Case Study 5

A male patient aged 43 years experienced chronic hepatitis B for over 30 years.

CT perfusion scanning of the liver demonstrates obviously increased blood flow in the hepatic artery along with progress of the conditions, significantly increased average passing time of the blood flow through the liver parenchyma, and decreased hepatic blood volume and hepatic blood flow. These findings may be related to obstructed blood flow in the portal vein due to swollen hepatocytes, compression of hepatic sinusoid, and increased interstitial fibers.

MR Imaging

Routine MR Imaging

The demonstrations include shrinkage of the liver volume, improper proportion of hepatic lobes, irregular liver margins, and a small amount of subcapsular effusion. The signal from the liver parenchyma is significantly uneven, especially in delayed phase by contrast imaging, with diffuse spots of low-signal shadows (Fig. 30.12). Circular edema in T1WI low signal and T2WI high signal can be found around the portal vein, which is more favorably demonstrated by MRCP. The gallbladder wall is thickened with edema that forms bilayer phenomenon. Edema of loose connective tissue in the outer membrane layer can be found, with a high T2WI signal. The thickening of mucosa and muscle layer is not obvious, with shrinkage or disappearance of gallbladder lumen.

Enlarged portal lymph nodes are sometimes the only MRI demonstration in the cases of acute or chronic viral hepatitis. By fat suppression FSE T2WI, the signal intensity of extrahepatic lymph nodes increases along with increased activity of chronic viral hepatitis. The enlarged lymph nodes are commonly distributed along with lymphatic drainage area in the liver and bile duct, namely, from the hilum to the first segment level of the duodenum. The causes of these findings remain unknown, which may be related to viral replication and immune-mediated inflammatory responses. The quantity of enlarged lymph nodes is related to the degree of hepatitis reactions and histological changes. The decreased quantity of enlarged peripheral lymph nodes demonstrates histological improvement of the patients after therapeutic intervention.

Dynamic contrast MR imaging demonstrates intrahepatic patches of enhancement in the early stage, indicating present or recent hepatocytic lesions. The intrahepatic linear enhancement in the late stage indicates hepatic fibrosis. In the delayed phase, the enhancement intensity of the liver parenchyma gradually increases along with the decreased hepatic functions, with delayed enhancement peak of the liver parenchyma. This is possibly related to decreased velocity of the blood flow in the portal vein.

Case Study 6

A female patient aged 41 years was diagnosed with hepatitis B.

Fig. 30.12

Chronic viral hepatitis. (a–d) Contrast MR imaging demonstrates slightly improper proportion of the liver lobes and no abnormally enhanced lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree