This article summarizes myelopathy and radiculopathy caused by different viruses. The cases described are divided into three categories: acute myelitis and radiculitis, postinfectious myelopathy and radiculopathy, and chronic myelopathy. Some diseases present with characteristic imaging findings. For example, varicella zoster virus tends to injure the dorsal column, whereas poliovirus tends to injure the frontal horns. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is an essential tool in diagnosis. However, because imaging findings are often nonspecific, consideration of a combination of diagnostic procedures, including the clinical course, symptoms, and laboratory data, is necessary for making a correct diagnosis.

Key points

- •

Patients with viral infections of the spinal cord and roots present with various clinical and radiologic manifestations that are induced by either direct injury from infection and/or indirect injury via the autoimmune processes.

- •

A combination of clinical information, including the clinical course, symptoms, laboratory data, and imaging, is essential for making a correct diagnosis.

- •

The time course and anatomic distribution are particularly important for differential diagnosis.

Myelitis and radiculitis are characterized by inflammatory processes of the spinal cord and nerve roots, respectively. Many different types of viruses can affect the spinal cord and roots, and infants to elderly patients are affected. Viral infection of the spinal cord is rare and is thus frequently misdiagnosed. Viral infection can directly destroy the cells of the spinal cord and roots or can cause demyelination and inflammation from abnormal immune responses of the host. The latter is usually called myelopathy, rather than myelitis.

Very few tools allow absolute diagnosis of myelopathy and radiculopathy. Almost all myelopathies and radiculopathies are therefore included in differential diagnosis for viral infections ( Box 1 ). To reach a correct diagnosis, a detailed clinical history, neurologic examination, laboratory tests, and imaging examination are necessary.

- 1.

Infectious myelitis

- i.

Viral myelitis

- a.

Varicella zoster virus

- b.

Herpes simplex virus

- c.

Cytomegalovirus

- d.

Epstein-Barr virus

- e.

Enterovirus (poliovirus, enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus, echovirus)

- f.

Rabies virus

- g.

Flavivirus (Japanese encephalitis), West Nile virus

- h.

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1

- i.

Human immunodeficiency virus

- a.

- ii.

Bacterial, fungal, and parasite myelitis

- a.

Mycoplasma

- b.

Lyme disease

- c.

Pyogenic myelitis

- d.

Tuberculosis

- e.

Syphilis

- f.

Fungi and parasites

- a.

- i.

- 2.

Noninfectious myelitis/myelopathy

- a.

Postinfection, postvaccination (related to measles, rubella, mumps, influenza, mycoplasma, streptococcus pneumonia, and so forth)

- b.

Multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- c.

Autoimmune disorders (systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–related vascultiis, atopic myelitis, and so forth)

- d.

Sarcoidosis

- e.

Behçet’s syndrome

- f.

Paraneoplastic syndrome

- a.

The complicated tract decussation of the spinal cord and roots can complicate the interpretation of neurologic examinations. Symptoms, such as paraplegia, quadriplegia, gait disturbance, sensory impairment, and bowel or bladder dysfunction, imply the presence of myelopathy. Myelitis is possible when these symptoms occur acutely and when one excludes the possibility of a compressive spinal cord lesion, neoplasm, or vascular lesion including infarction and hemorrhage.

Radiculopathy sometimes shares common neurologic symptoms with myelopathy. Important points to consider for differentiation are the tendon reflex and the type of paralysis. Radiculopathy can present with tendon hyporeflexia and flaccid paralysis, whereas myelopathy can show tendon hyperreflexia and spastic paralysis. Muscle atrophy is common in radiculopathy but less so in myelopathy. However, myelopathy and radiculopathy can occur simultaneously because viral infection can occur in the spinal cord and roots at the same time.

The speed of onset and clinical course are the most important types of information needed for diagnosing neurologic disorders. Most vascular lesions have a sudden onset, and the symptoms reach completion immediately. Demyelination, including that seen in multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica, is polyphasic. Neoplasms generally have a progressive course. Degenerative and congenital diseases are usually slowly progressive, although degeneration can fluctuate. Inflammation including viral infections shows a varied course, ranging from acute to chronic. Acute myelitis and radiculitis are frequently associated with fever, fatigue, and skin rash. Herpes viruses, such as varicella zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes simplex virus, and enteroviruses including poliovirus and enterovirus 71, can show acute onset and progression of symptoms.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), and acute transverse myelitis (ATM) often appear 7 to 10 days after the onset of infection. Chronic and progressive myelitis can be caused by retroviruses, such as human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), causing HTLV-1–associated myelopathy (HAM). Some patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may also present with myelopathy.

Examination of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) often leads to a final diagnosis, but the sensitivity is often low. Blood tests should look for autoimmune antibodies, which indicate autoimmune disorders; angiotensin-converting enzyme, which indicates sarcoidosis; and IgE, which indicates parasite infection and atopic myelitis. CSF examination can be performed to look for antibodies, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can detect the viral genome. CSF should be evaluated for oligoclonal bands to diagnose multiple sclerosis. PCR for viral DNA is sometimes negative even though antibodies are detectable. The ability to directly identify the virus strongly depends on the timing of CSF sampling. Electrophysiologic tests are often useful for evaluating peripheral nerves, and this technique can prove the presence of radiculopathy and distinguish axonal injury from demyelination of the nerves.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is an essential tool in diagnosis. However, because imaging findings are often nonspecific, consideration of a combination of the previously mentioned diagnostic procedures, including the clinical course, symptoms, and laboratory data, is necessary for making a correct diagnosis. One of the most important roles of MR imaging is to exclude other disorders, especially compressive cord lesions and vascular lesions.

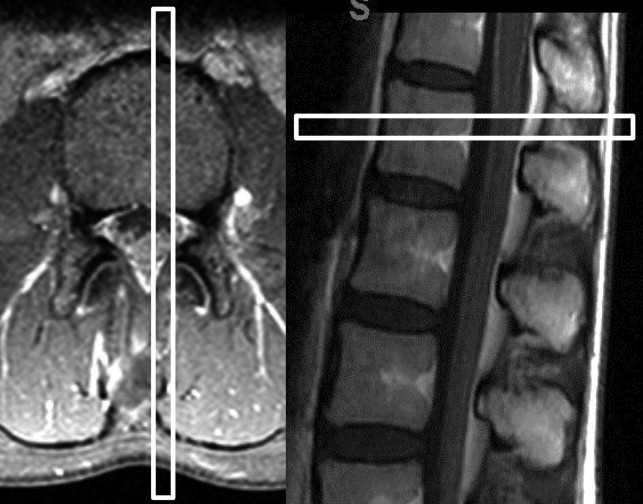

Sagittal and axial image acquisitions are fundamentally important. Sagittal images provide an overview of the spinal cord and the roots. Transaxial images better depict detailed structures. For instance, because of decreased partial volume averaging for axially oriented lesions, the presence of contrast enhancement of the cord and the cauda equina is often more apparent on transaxial slices ( Fig. 1 ). T2-weighted imaging is one of the most important sequences for detecting lesions and evaluating their distribution. Precontrast- and postcontrast-enhanced T1-weighted images are also essential for detecting abnormal vasculature and evaluating activity of the lesions. Detailed comparison between precontrast and postcontrast T1-weighted images is especially needed for the cauda equina because enhancement of this structure is sometimes vague. The number of lesions, length of the involved cord, presence or absence of atrophy or swelling, and anatomic distribution of signal abnormalities are important features to interpret. Some diseases present with characteristic imaging findings. For example, VZV tends to injure the dorsal column, whereas poliovirus tends to injure the frontal horns.

In the following sections are summarized the myelopathy and radiculopathy caused by different viruses. The cases described are divided into three categories: (1) acute myelitis and radiculitis, (2) postinfectious myelopathy and radiculopathy, and (3) chronic myelopathy.

Acute myelitis and radiculitis

Varicella Zoster Virus

VZV is a relatively well-documented cause of viral myelitis ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). VZV usually causes encephalomyelitis, and exclusive involvement of the spinal cord has rarely been documented. Damage to the spinal cord is induced by VZV infection, excessive immune response, and vasculitis. Clinical diagnosis of VZV myelitis is usually established by the typical time course between occurrence of a skin rash and subsequent spinal cord symptoms. Myelitis occurs after a few days to weeks from the onset of the skin rash. Additional tests may be necessary, especially in immunocompromised patients who may lack the preceding skin rash, although the sensitivity of such tests may not be sufficiently high. Quick tests of choice include PCR and/or direct detection with fluorescent antibodies, the results of which can be obtained within a few hours. Viral culture, however, requires prolonged incubation and sensitivity that is lower than that of PCR. Antibodies to VZV in the CSF may be useful for diagnosing VZV myelitis. Serum antibodies, however, are often detected in patients with a history of prior infection of VZV and are thus nonspecific. Laterality between skin rash and neurologic symptoms usually matches because VZV reaches the spinal cord via the dorsal nerve root. Unilateral or asymmetric motor/sensory disturbances and bowel/bladder dysfunctions can occur.

Pathologic evaluation often shows that the entry portion of the dorsal root and the posterior column are strongly damaged. Vertical extension along the cord is also often observed. The level of the skin rash and the level of the spinal cord lesions usually match on pathologic examinations, although some discrepancy can occur.

MR imaging can show pathologic changes with preferential involvement of the ipsilateral dorsal column and posterior horn. Lesions may show enhancement in the acute phase. These imaging findings are characteristic and useful for making the diagnosis. VZV myelitis sometimes presents in long segments. Radiculitis has also been reported.

Poliovirus

Acute poliovirus infection is typically characterized by flaccid paralysis, and is a typical pathogen causing anterior horn myelitis ( Fig. 4 ). Vaccination can dramatically reduce the incidence of poliomyelitis. New cases of poliomyelitis that we encounter are often related to live vaccination, although its incidence is now extremely low, because the inactivated vaccine is becoming more popular.

Patients with a previous history of poliomyelitis sometimes have new or progressive disability including muscle weakness, numbness, and pain that occurs 10 to 50 years after the initial onset of myelitis. This condition is called postpolio syndrome (PPS) and is not a recurrence of poliomyelitis but a secondary disorder. Even light exercise can overload muscles already damaged by poliomyelitis and cause secondary nerve and muscle degeneration. In addition, aging changes and muscle disuse can accelerate the weakness. The incidence of PPS is 40% to 60% in patients with previous poliomyelitis. PPS has no pathognomonic clinical findings. Laboratory tests, electromyography, and muscle biopsy are mainly used to exclude other diseases.

On MR imaging, acute-phase poliomyelitis is characterized by localized unilateral or bilateral signal abnormalities in the anterior horn. These signal changes often remain until the chronic phase. No specific imaging sign for PPS exists, and MR imaging cannot distinguish patients with previous poliomyelitis with PPS from those without symptoms of PPS. MR imaging for PPS is therefore used to exclude other causes of progressive disability.

Enterovirus 71

Acute flaccid paralysis is not specific for poliovirus infection but can be caused by various other viruses, including coxsackievirus, Japanese encephalitis virus, echovirus, or enterovirus. This condition is known as polio-like syndrome and generally has better prognosis than poliomyelitis.

Enterovirus 71 is a cause of hand-foot-and-mouth disease ( Fig. 5 ). Acute flaccid paralysis caused by enterovirus 71 radiculomyelitis has been recently documented in young children. Clinical symptoms are similar to poliomyelitis, but enterovirus 71 tends to present with myoclonus, tremor, or ataxia. The diagnosis can be made by virus isolation, PCR of CSF, or a throat swab. The sensitivity of PCR is generally superior to virus isolation using cell culture. The serology test is limited for routine diagnosis of enterovirus infections because the method is not feasible to test multiple live viral antigens and is relatively insensitive. On MR imaging, the anterior horns and ventral nerve roots are predominantly involved, and dorsal roots are usually spared. These imaging findings closely reflect the clinical symptoms. Enterovirus can also cause rhombencephalitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree