FIGO category

Description

Stage I

Tumor confined to the vulva

IA

Lesions ≤2 cm in size, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤1.0 mm, no nodal metastasis

IB

Lesions >2 cm in size or with stromal invasion >1.0 mm, confined to the vulva or perineum, with negative nodes

Stage II

Tumor of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, and anus) with negative nodes

Stage III

Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, and anus) with positive inguinofemoral lymph nodes

IIIA

With 1 lymph node metastasis (≥5 mm) or 1–2 lymph node metastases (<5 mm)

IIIB

With 2 or more lymph node metastases (≥5 mm) or 3 or more lymph node metastases (<5 mm)

IIIC

With positive nodes with extracapsular spread

Stage IV

Tumor invades other regions (2/3 upper urethra, 2/3 upper vagina) or distant structures

IVA

Tumor invades any of the following: Upper urethra and /or vaginal mucosa, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or fixed to pelvic bone, or fixed or ulcerated inguinofemoral lymph nodes

IVB

Any distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes

Table 5.2

Survival rates for squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, by stage

Stage | Relative survival rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

5 Years | 10 Years | |

I | 93 | 87 |

II | 79 | 69 |

III | 53 | 46 |

IV | 29 | 16 |

5.1 Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis of vulvar cancer and the assessment of superficial lymph node involvement are usually done clinically. Vulvar cancer is surgically staged. The early-stage vulvar cancers are treated surgically by radical wide excision of the primary lesion and inguinal lymphadenectomy [21–24]. Appropriate groin node dissection is the single most important factor in reducing mortality from vulvar cancer. Surgery is the treatment of choice even for locally advanced cancer, although neoadjuvant radiation and chemotherapy may be used either to enable surgery in a case initially deemed “inoperable” or to avoid exenteration in elderly patients.

5.2 Imaging

Imaging has a limited role in the evaluation of the primary site of disease in vulvar cancer, as this is readily assessed clinically. MRI may be helpful in evaluating the extent of disease in patients with advanced tumor involving the perineum, vagina, and anal canal. MRI is the best imaging modality to accurately assess the local extent of vulvar cancers for surgical planning, and to detect lymph node metastasis [25–32]. The size of the tumor and the involvement of the urethra, anus, and levator ani muscle can be defined with MRI. Clinically relevant information is whether the mass is less than or larger than 2 cm in size, as well as the depth of invasion. Nodes are evaluated by location, size, and morphology, with necrosis and large size having a high degree of specificity for metastatic disease. MRI can be highly specific in identifying abnormal lymph nodes by using size criteria and morphology, but sensitivity is low, ranging from 40 to 50 % [26]. Other criteria, including the ratio of the short axis to the long axis (S/L ratio), contour, presence of cystic changes/necrosis, loss of fatty hilum, and signal intensity, have been examined to improve sensitivity and accuracy [26]. The S/L ratio is a good quantitative maker for diagnosing lymph node metastasis, with 87 % sensitivity and 81 % specificity [26]. Protocols for MRI imaging of the pelvis use a torso coil with the patient in a supine position. Images include axial T1-weighted images, axial T2-weighted images with fat saturation, and axial, sagittal, and coronal T2-weighted precontrast and multiphase postcontrast images.

CT scans are useful to detect lymph nodes or other distant metastases. The use of positron emission tomography (PET) for patients with vulvar cancer is undefined [27, 28]. One prospective surgical study was performed, evaluating fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET before groin surgery for patients with vulvar cancer. PET/CT had a sensitivity of 67 %, a specificity of 95 %, a positive predictive value of 86 %, and a negative predictive value of 86 % [27, 28]. For detection of extranodal disease, FDG-PET demonstrated high specificity and accuracy [27, 28].

Ultrasound is used mainly to detect abnormal inguinal lymph nodes or for ultrasound-guided biopsy of suspicious lymph nodes. Focused ultrasound imaging is performed using a high-frequency transducer (linear 8–18 MHz).

5.3 Recurrence

Recurrence of vulvar cancer is most common in the vulvar region (43–50 %) [33–35]. The groin is the site of 6–30 % of recurrences. Groin recurrences develop earlier than vulvar recurrences, and the prognosis of these patients is much worse. Pelvic recurrences are rare, constituting about 5 % of all recurrences. Distant recurrences make up 8–23 % of all recurrences and are associated with a dismal prognosis.

5.4 Normal Anatomy

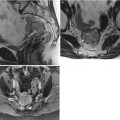

Fig. 5.1

The vulva refers to external female genitalia. It is comprised of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibular bulb, vestibular glands, and the vestibule of the vagina. It appears as a triangular soft-tissue structure within the perineum, bounded by the symphysis pubis anteriorly, the anal sphincter posteriorly, and the ischial tuberosities laterally. (a) An axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows the vulva (arrows) situated anterior to the anus (A). (b) Axial T1-weighted MR imaging demonstrates the vulva as intermediate in signal intensity (arrows). (c) Axial T2-weighted MR imaging shows the vulva as having intermediate to high signal intensity (arrows)

5.5 Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma

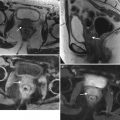

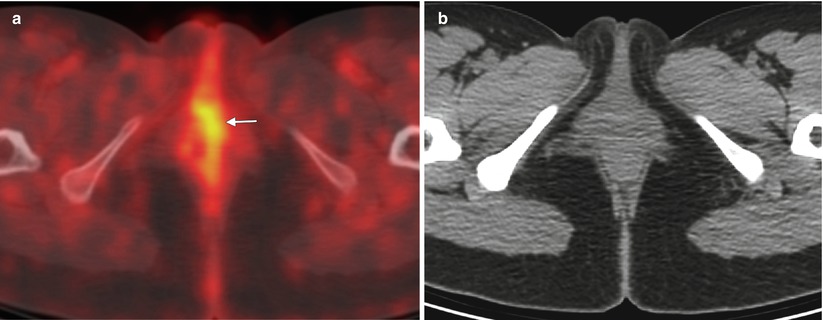

Fig. 5.2

Stage I vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Currently, the standard treatment for vulvar cancers includes radical wide excision of the primary lesion with at least 1 cm of clear surgical margin [21–24], with unilateral or bilateral lymphadenectomy. Appropriate groin node dissection is the single most important factor in reducing mortality from vulvar cancer. However, the morbidity associated with lymphadenectomy is considerable. Sentinel lymph node excision is now being recommended in selected patients with early-stage SCC as a means to avoid the operative morbidity associated with inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy [15–17]. The optimal candidates for sentinel lymph node mapping are patients who have a lesion less than 4 cm in diameter with nonpalpable groin lymph nodes. The combination of radiotracer and blue dye is the most accurate technique for sentinel node detection. Patients with a positive sentinel node should undergo a full inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy followed by postoperative radiation therapy to the involved groin and pelvis. However, if sentinel lymph nodes are negative, no further treatment is indicated. The false negative rate of sentinel node biopsy is extremely low, 2–5 %. This 28-year-old woman presented with approximately 1 year of clitoral irritation. A right vulvar biopsy showed invasive SCC. The lesion was 0.8 cm in size, with depth of invasion of 1 mm or less (stage I disease). (a) An axial fused fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)/CT scan showed mild focal tracer uptake in the vulvar region (arrow), without evidence of nodal involvement or distant metastatic disease. (b) The CT component of the PET/CT scan without contrast enhancement did not show any obvious vulvar lesion. CT has poor contrast resolution, however, so it does not delineate this mass. The patient underwent radical vulvectomy, including clitorectomy with bilateral sentinel lymph node dissection

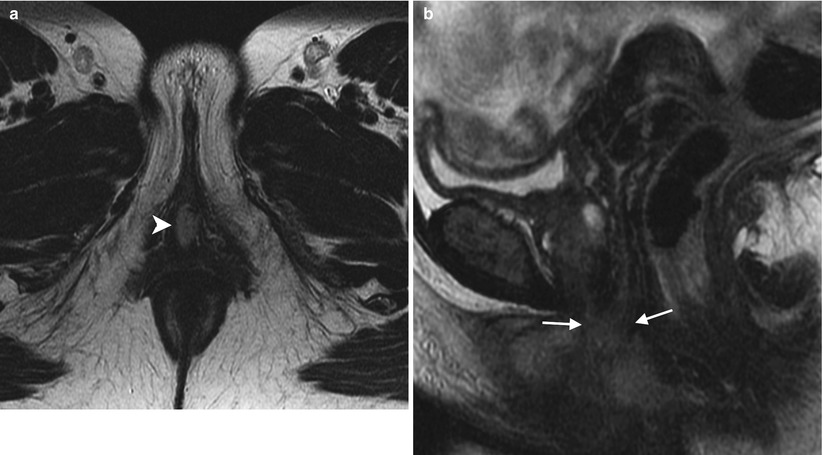

Fig. 5.3

Stage II vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), positive for human papillomavirus (HPV). In the vulva, about 40 % of malignancies can be linked to HPV [5]. Most cases of HPV-associated vulvar SCC occur in association with the HPV types known to be oncogenic: HPV 16, 18, or 33. HPV-positive vulvar SCC occurs in younger women and has strong association with smoking and with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm (VIN). These cancers tend to be early-stage disease with multifocal lesions and can be combined with cervical cancer, vaginal cancer, or perianal cancer. A vulvar lesion was recently diagnosed in this 47-year-old woman, a long-time smoker. The lesion showed moderately differentiated SCC and was suggested to be HPV-positive on biopsy. Axial T2-weighted MR image (a) and a sagittal T2-weighted image (b) showed a midline vulvar mass with high signal intensity (arrowhead), extending to and abutting the posterior aspect of the urethral meatus and the most distal part of the vagina (arrows). Another axial T2-weighted image (c) showed a borderline-enlarged left external iliac lymph node (curved arrow). An axial T1-weighted image with gadolinium (d) demonstrated avid enhancement of the vulvar mass (arrowhead). Axial fused FDG-PET/CT scans (e, f) showed tracer uptake of the vulvar mass (arrowhead) and only low-grade uptake in the left external iliac lymph node (curved arrow), which was likely a reactive lymph node (stage II disease). Sentinel lymph node mapping using Tc-99m sulfur colloid and blue dye showed two hot and blue left superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Both left superficial inguinal lymph nodes were removed during the surgery and were proven to be benign lymph nodes by pathology. Lymph flow passes from the primary tumor to the sentinel lymph node and afterwards to other nonsentinel lymph nodes. Thus, the sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node that received lymphatic drainage from a lesion on the vulva [15–17]. If the sentinel lymph node is free of metastatic disease, the rest of the nodes in the lymphatic chain theoretically should also be free of tumor

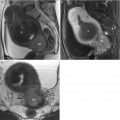

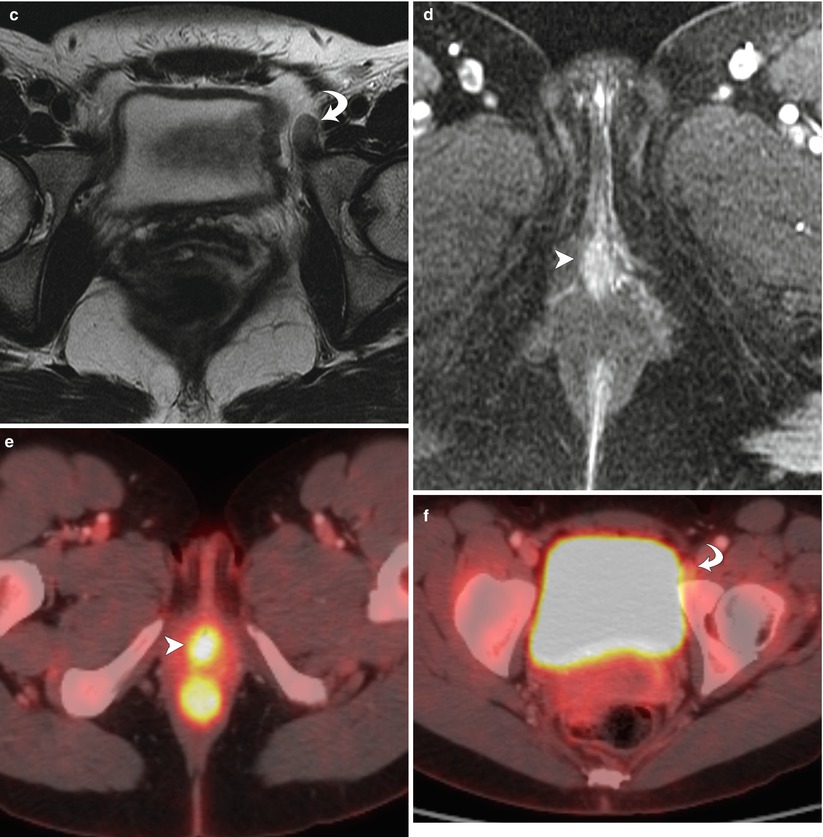

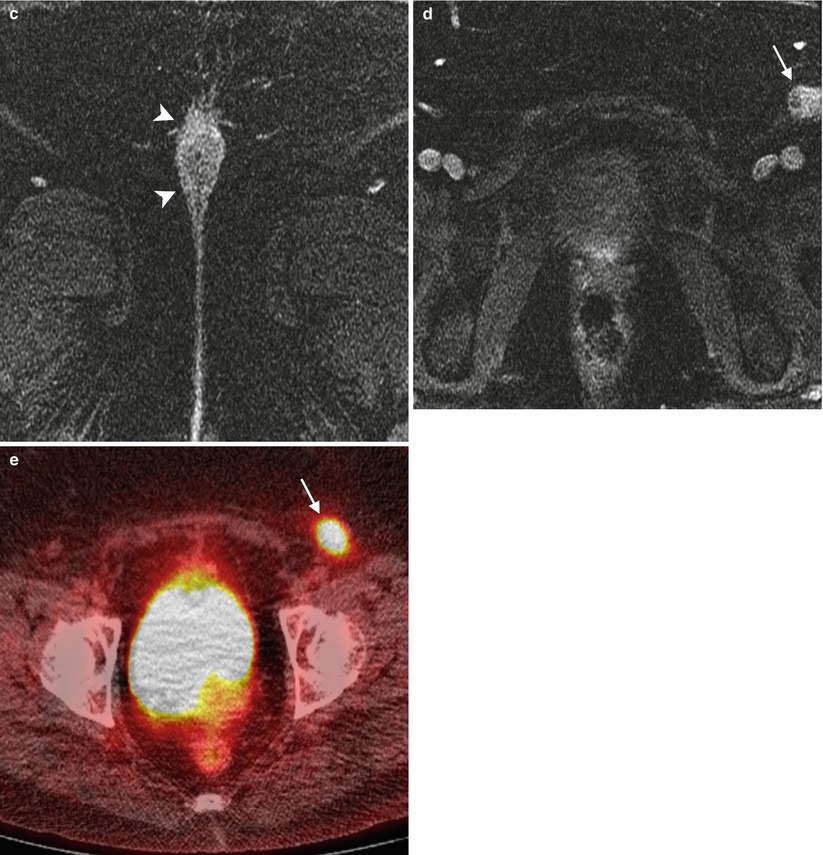

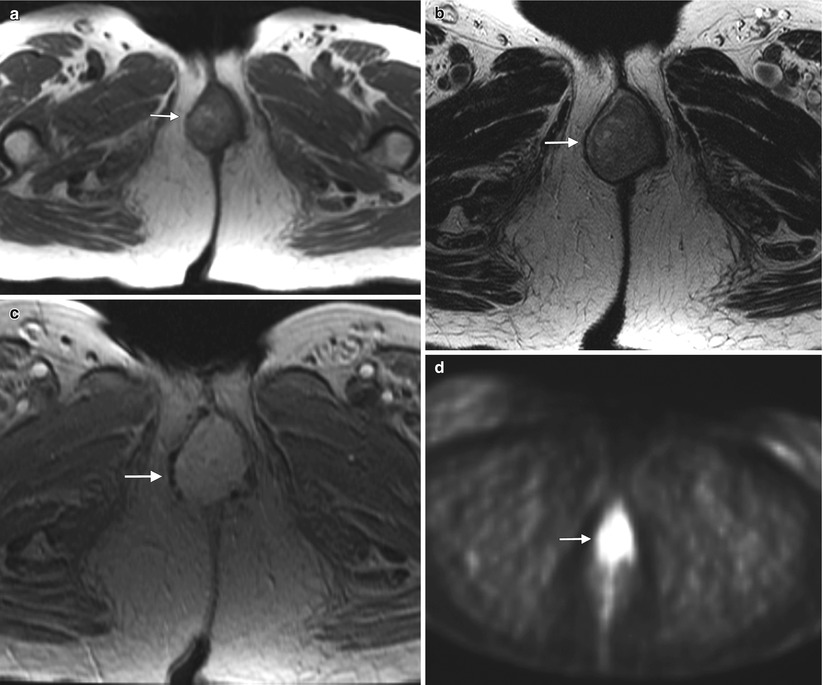

Fig. 5.4

Stage III vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The lymphatic drainage of the vulva has been studied extensively. Typically, vulvar carcinoma metastasis is through nodal spread, which occurs first in superficial inguinal lymph nodes, followed by deep inguinal lymph nodes (below the cribriform fascia). Metastasis to deep pelvic lymph nodes, such as the internal or external iliac lymph nodes, is considered to be a distant metastasis [2, 12]. Generally, lateralizing lesions (1 cm beyond the midline) drain to the ipsilateral superficial inguinal lymph nodes, whereas midline lesions can drain to either side. It is extremely rare for lateralizing vulvar cancers to spread to the contralateral inguinal lymph nodes if there is no evidence of ipsilateral lymph node metastases. Likewise, it is unusual for the deep inguinal lymph nodes to be involved in the absence of superficial inguinal lymph node spread [15]. This 56-year-old woman complained of pruritus and tenderness in the vulvar region for more than 1 year. Recently, right vulvar biopsy showed invasive SCC. (a, b) Coronal and axial T2-weighted MR imaging showed a midline vulvar mass with high signal intensity (arrowheads) and an enlarged left superficial inguinal lymph node with cystic change (arrow). (c, d) Axial T1-weighted imaging with gadolinium demonstrated avid enhancement in the vulvar mass (arrowheads) and a left superficial inguinal lymph node containing cystic change (arrow). (e) Axial fused FDG-PET/CT imaging demonstrated tracer uptake in the left superficial inguinal lymph node (arrow) (stage III disease). The patient underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by partial vulvectomy and left inguinal lymph node dissection

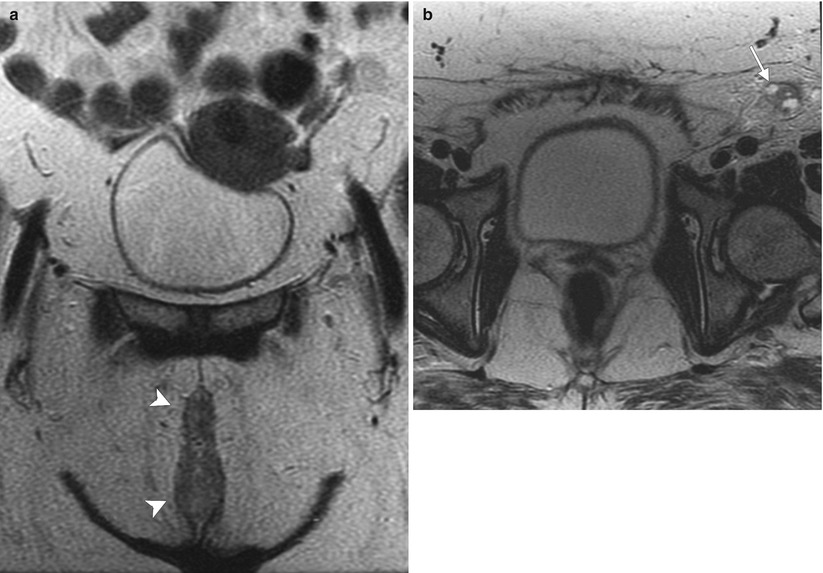

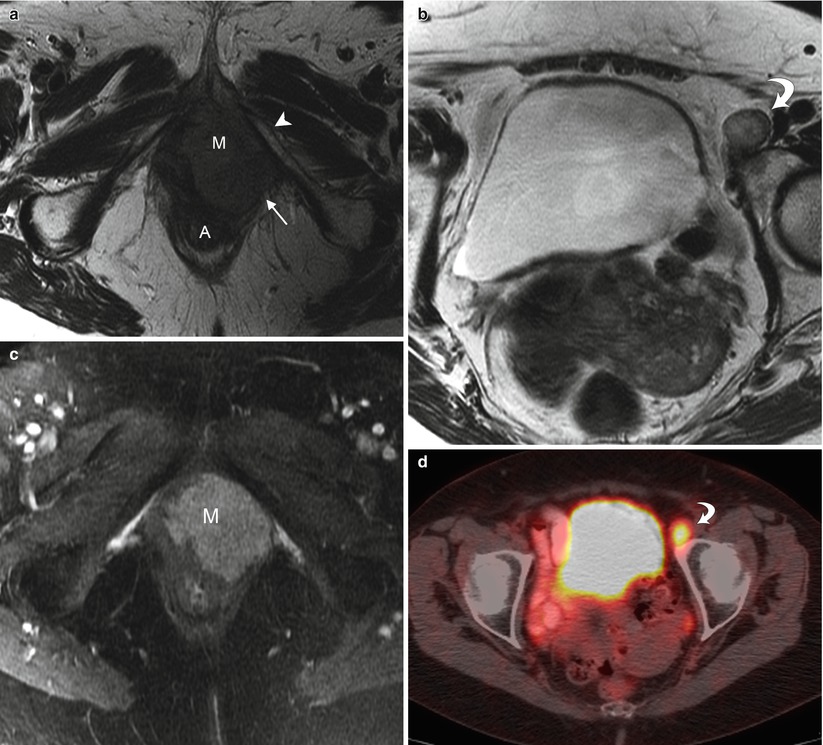

Fig. 5.5

Stage IV vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). This 80-year-old woman complained of irritation and enlargement of the left labia for several months. Left labial biopsy showed invasive SCC. (a, b) Axial T2-weighted MR imaging showed a high signal intensity mass in the left labia (M) and an enlarged left external iliac lymph node (curved arrow). The left labial mass invades through the pelvic floor, with involvement of the posterolateral urethra, lower vagina, and anal wall (A). The mass invaded the left levator ani muscle (arrow), and fixed to the left inferior pubic ramus (arrowhead). (c) Axial T1-weighted imaging with gadolinium showed avid enhancement of the left labial mass (M). (d, e) Axial and coronal fused FDG-PET/CT scans demonstrated tracer uptake of left labial mass (arrow) and left external iliac lymph node (curved arrow). Left external iliac lymph node metastasis is considered to be distant metastasis. Therefore, this is stage IVB disease

5.6 Local Recurrence of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma

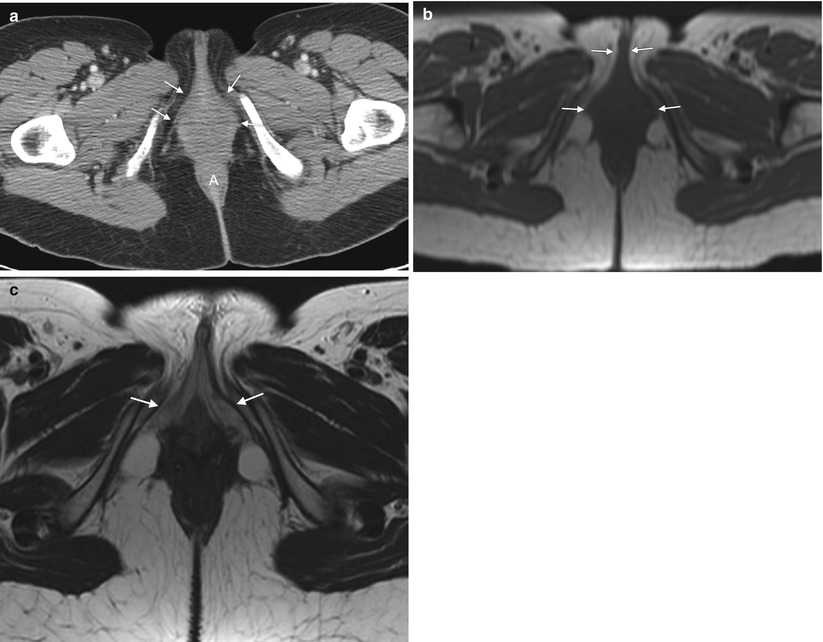

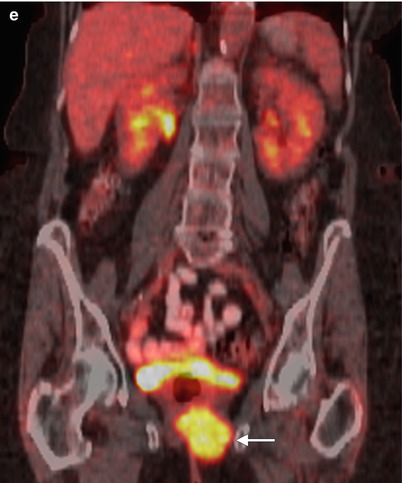

Fig. 5.6

Local recurrence of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The most common site of recurrence for vulvar cancer is the vulvar region (43–54 %) [34]. The groin is the site of 6–30 % of recurrences. Groin recurrences usually develop earlier than vulvar recurrences, and prognosis is much worse compared with patients with a recurrence on the vulva. Though local recurrences may be controlled with a new, wide local excision, radiotherapy, or both, groin recurrences are usually fatal [34, 35]. Pelvic recurrences are rare, accounting for about 5 % of all recurrences. Distant recurrences comprise 8–23 % of all recurrences and are associated with a dismal prognosis. This 75-year-old woman had a long history of squamous urothelial cancer, which was being treated by urologists. She developed vulvar SCC years ago and was treated with radiation at another institution. Now she presents with a right vulvar recurrent mass. Axial contrast-enhanced CT images (a–c) and a sagittal reformatted CT scan (d) showed a right vulvar mass (arrow), which involved the urethra (curved arrow), rectum (R), and lower vagina (arrowheads). There was no evidence of lymph node or distant metastases

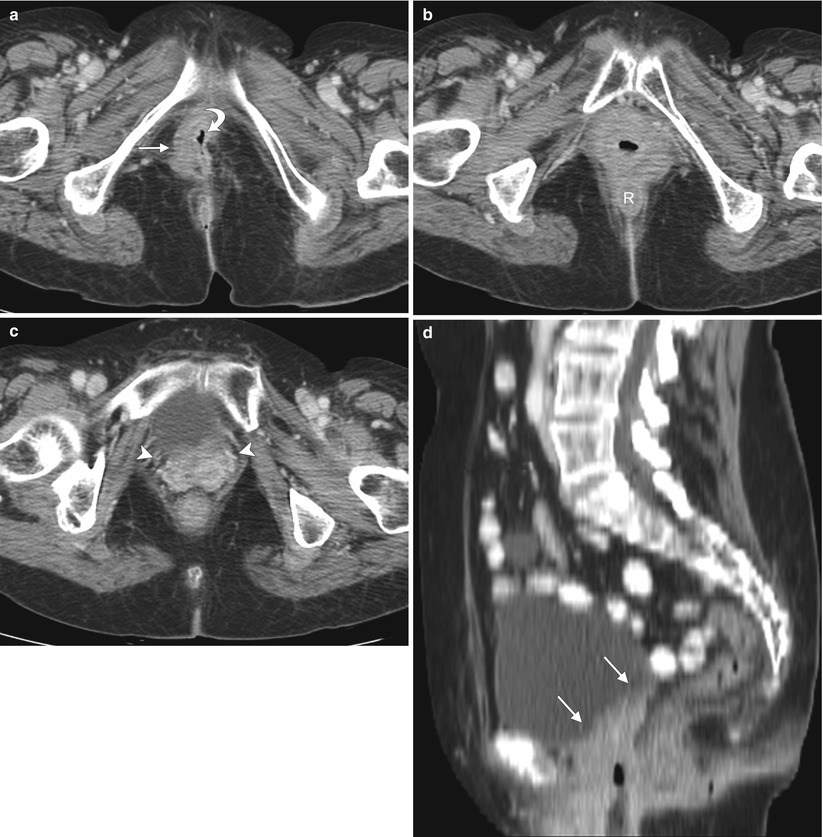

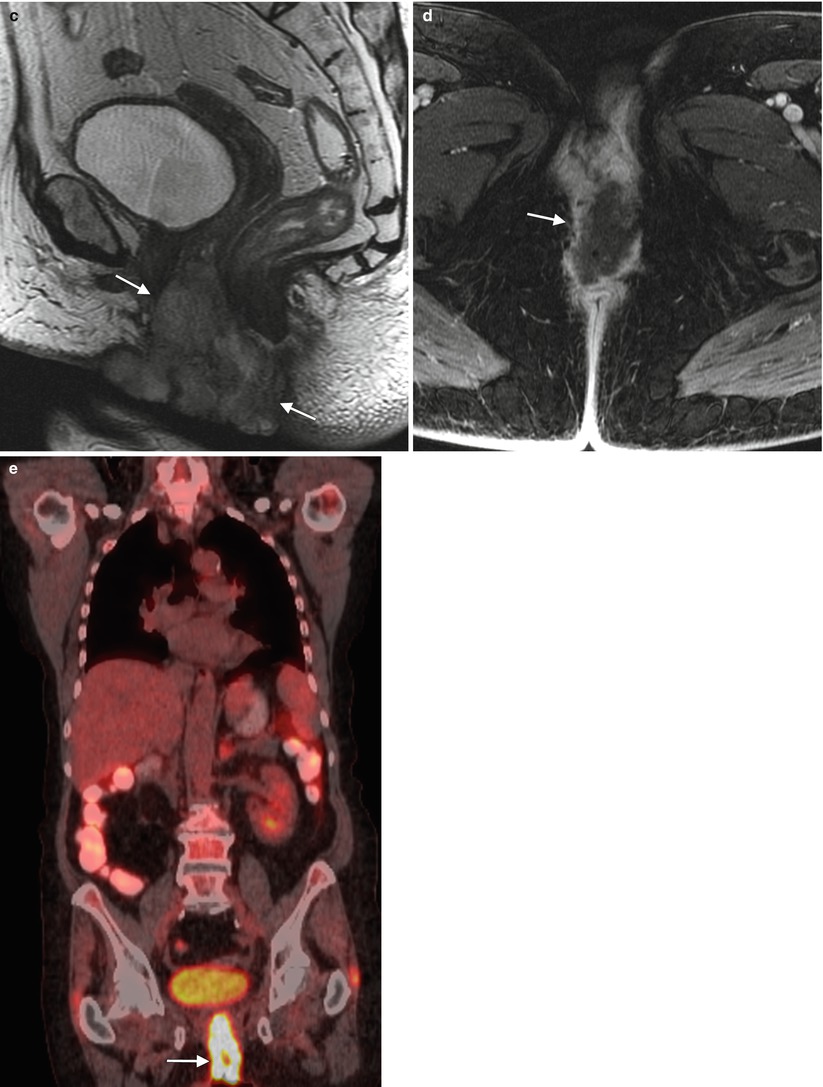

Fig. 5.7

Local recurrence of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Pelvic exenteration has progressively evolved into a potentially curative salvage therapy for locally advanced disease, and for central pelvic recurrence after prior radiation [36–38]. However, it comes with significant risks, associated morbidity, and impact on quality of life. The procedure-related mortality is approximately 3–5 %, and morbidity is also high, with complication rates approaching 60 % [37]. Imaging studies such as PET/CT and ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration, as well as laparoscopic evaluation, have enabled physicians to more accurately assess the extent of disease preoperatively, refining the choice for candidates for exenteration [36–38]. This 78-year-old woman underwent radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection for vulvar SCC 7 years ago. There was no evidence of inguinal or distant metastases at that time, but 3 years later she developed local recurrent disease, which was treated with wide excision and chemoradiation therapy. Recently, she presented with locally advanced current disease. (a–c) Axial, coronal, and sagittal T2-weighted MR imaging showed a vulvar mass with high signal intensity (arrows), which invades the urethra and anus. (d) Axial T1-weighted imaging with gadolinium showed avid enhancement of the vulvar mass (arrow). (e) Coronal fused FDG-PET/CT imaging showed tracer uptake of the mass (arrow), determined to be locally advanced disease without evidence of distant metastases on PET/CT. The patient underwent total pelvic exenteration with reconstruction. Unfortunately, she had postoperative complication (abdominal sepsis) and was admitted to the intensive care unit. Three months later, she developed extensive distant metastases, including pleural, lung, and liver metastases

5.7 Other Vulvar Malignancies

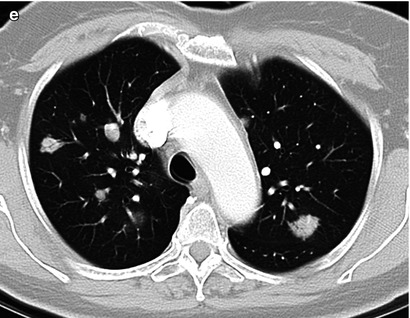

Fig. 5.8

Vulvar melanoma. Melanoma is the second-most-common vulvar cancer histology, accounting for about 5–10 % of primary vulvar cancers. It represents a subtype of cutaneous melanoma, with similar prognostic and staging factors. The most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 2009 staging system for cutaneous melanoma (Tables 5.3, 5.4, 5.5, and 5.6) is applicable to vulvar melanoma [7, 8]. Vulvar melanoma is an aggressive disease, carries a poor prognosis (Table 5.7), and tends to recur locally as well as to develop distant metastases through hematogenous dissemination [6–9]. Surgical excision represents the single best definitive therapy for this neoplasm, which has a limited response to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy [8]. This 68-year-old woman had a history of vulvar melanoma and underwent vulvectomy 9 years ago. She developed local recurrence 7 years ago, which was treated with surgical excision. Recently, she noted some bright red blood in the perineal area. On physical examination, a periurethral mass in the vulvar region was noted and biopsy revealed recurrent melanoma. An axial T1-weighted MR image (a) and an axial T2-weighted image (b) showed a periurethral mass (arrow) in the vulvar region, which had high signal intensity on both the T1- and T2-weighted images. A vulvar melanoma typically shows high signal intensity on T1-weighted images because of the paramagnetic effect of the melanin content. Occasionally, the signal on a T1-weighted image may be low or intermediate in cases with low melanin content within the lesion (amelanotic melanoma). An axial T1-weighted image with gadolinium (c) showed avid enhancement of the mass (arrow). An axial FDG-PET scan (d) demonstrated tracer uptake of the mass (arrow), and an axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (e) showed multiple pulmonary metastases

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree