Fig. 34.1

Sit-up test with pressure at the inferior rectus abdominus

In addition to this examination, a thorough bilateral hip examination is preformed, focusing on passive range of motion, asymmetry, and any pain production with hip motion. Impingement testing of the hip should be included in the physical examination to evaluate for femoroacetabular impingement.

The role of imaging modalities in the diagnosis of hip and groin pain, and specifically for athletic pubalgia, continues to evolve. We typically obtain an AP pelvis, AP and lateral hip, and 45° Dunn view, which has previously been shown to accurately diagnose cam FAI [8]. The Dunn view is particularly useful in detecting femoral neck lesions consistent with cam-type FAI. Several studies have demonstrated the improved accuracy of MRI over plain radiographs alone for establishing hip and groin diagnoses [9–14] and have even recommended that it be considered the “gold standard” for imaging of athletic pubalgia [10]. Other studies, however, have shown a high false-positive rate for this modality, with Silvis et al. reporting a rate of 77 % of pathologic hip or groin MRI findings in asymptomatic collegiate and professional ice hockey players [15].

For various reasons, including coexisting pathology, and the considerable anatomic overlap of anterior structures, diagnostic imaging is often required to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of athletic pubalgia. If other coexisting pathology is visualized on MRI, then information collected from the history and physical exam, as well as other diagnostic tools such as diagnostic injections, should be utilized to confirm the diagnosis of athletic pubalgia.

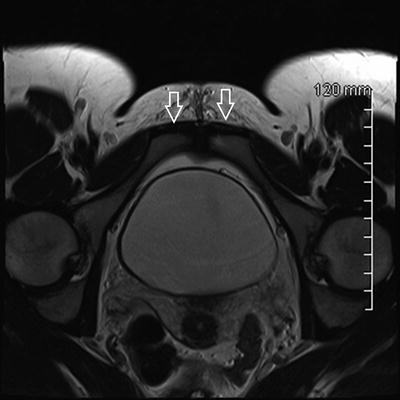

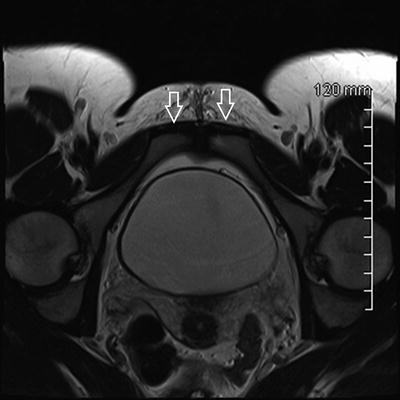

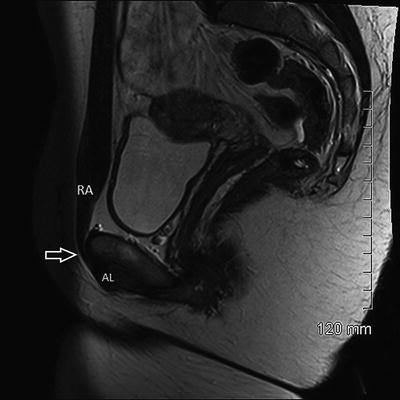

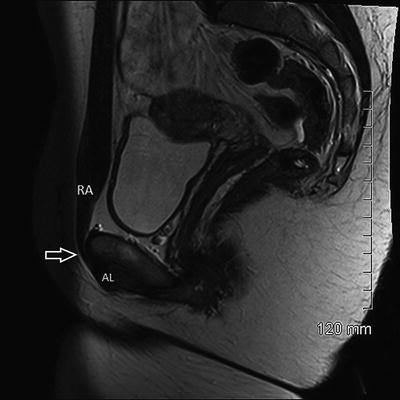

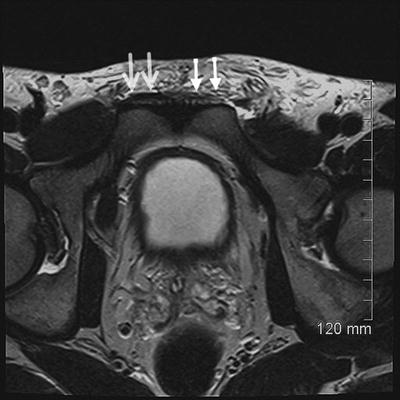

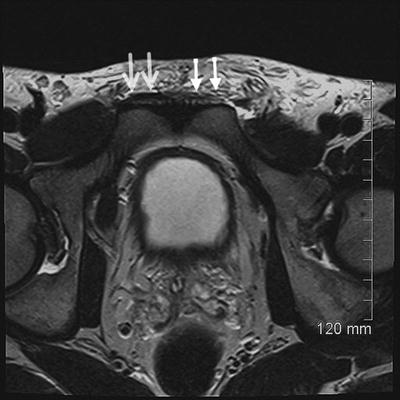

MRI is important for both the diagnosis of athletic pubalgia, as well as to evaluate for other conditions that may be causing the patient’s groin pain, including hip joint pathology, strains, labral tears, osteitis pubis, iliopsoas bursitis, and occult stress fractures. Fluid-sensitive sequences should be done in three orthogonal planes [16]. A key sequence is the axial oblique, which shows the aponeurosis of the adductor longus and rectus abdominis (Fig. 34.2). The plane of the axial oblique MRI should parallel the arcuate line of the pelvic inlet [17]. A secondary cleft sign is an indication of an aponeurotic tear. The secondary cleft sign is seen on the axial oblique MRI as a curvilinear region of high signal intensity adjoining the pubic symphysis, on the side of the groin pain. This is believed to represent a microtear at the origin of the adductor longus and gracilis tendons [18].

Fig. 34.2

MRI T2 sequence, axial oblique plane. Arrows represent normal appearing rectus abdominus–adductor longus aponeurosis

Fluid-sensitive sequences allow direct visualization of increased signal intensity, indicating a tear of the rectus abdominis–adductor longus aponeurosis, or a tear/avulsion of the adductor longus. Tears of rectus abdominis–adductor longus aponeurosis appear as fluid or increased signal intensity undermining the aponeurosis, indicative of a tenoperiosteal disruption [16]. MRI sagittal and axial fluid-sensitive images acquired approximately 1–2 cm lateral to the pubic symphysis display the tenoperiosteal disruption at the aponeurosis [16].

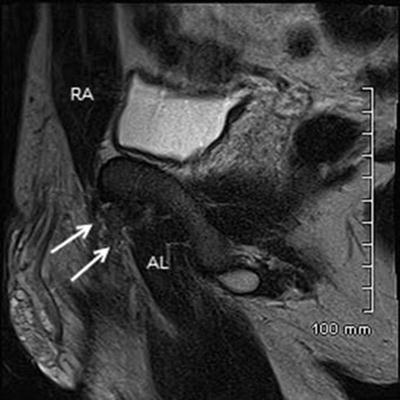

T2-weighted fat-suppressed sagittal images obtained 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphysis visualize the rectus abdominis muscle/tendon, the adductor longus muscle/tendon, and the aponeurosis (Fig. 34.3).

Fig. 34.3

MRI T2 sequence, sagittal plane. The rectus abdominus is marked, which continues to the aponeurosis (open arrow) anterior to the pubis, and transitions to the adductor longus tendon

Beyond the lack of consensus in diagnostic techniques and modalities, there also currently exists a multitude of both conservative [19, 20] and operative [21–25] indications and techniques, with a wide array of reported outcomes. Furthermore, much controversy exists in regard to the treatment of those patients who present with physical exam and/or radiographic findings consistent with both athletic pubalgia and femoroacetabular impingement.

The chief muscular injury involved in athletic pubalgia is the insertion of the rectus abdominus. It has been our experience that this region is most often attenuated, and that direct reinsertion of the tendon back to its pubic insertion site appears to achieve excellent and consistent results. One of the most critical steps in our open repair technique involves the diligent bony preparation of the pubic insertion site and widened reinsertion area of the rectus tendon. We believe that the success we have encountered with this repair is the result of spreading these muscular forces over a wider insertion point, thus creating a relative decrease in the concentrated forces applied through the tendon attachment.

Operative Technique

As previously described by Litwin et al. [3], operative treatment at our institution is based on the theory of either gross tears, or more commonly microtears, within the muscles of the lower abdominal region. This region of pathology involves the external oblique aponeurosis, rectus abdominus, interface of the rectus abdominus and conjoined tendon, internal oblique, or transversus abdominus. Muscular attenuation in the aforementioned regions may predispose the transversalis fascia of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal to further injury, creating a subsequent defect and resultant bulge when present [3]. The pain associated with athletic pubalgia is believed to arise from the muscle injury, and not the resultant posterior wall defect, which may or may not be present in any given case [3].

Our technique focuses primarily on the insertion of the rectus abdominus to the pubis, along with stabilization of the interface between the rectus and conjoined tendon, with reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal [3]. Figure 34.4 demonstrates the surface anatomy of the rectus abdominus insertion and site for skin incision.

Fig. 34.4

Surface anatomy of rectus abdominus insertion and planned skin incision

Appropriate preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is administered unless contraindicated. The patient is placed in a supine position and prepped and draped to allow access to the lower abdomen on the side of pathology. A small 5 cm skin incision is made just above the external inguinal ring (Fig. 34.5). Dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous fat and Scarpa’s fascia, exposing the underlying external oblique aponeurosis (Fig. 34.6).

Fig. 34.5

Incision along skin crease just proximal to external inguinal ring

Fig. 34.6

Exposed external oblique aponeurosis

Next, the external oblique is carefully incised in the direction of its fibers into the external inguinal ring, with care to avoid adjacent nerves (Fig. 34.7). The muscle is then elevated from the underlying structures, and the spermatic cord is identified and encircled with a penrose drain (Fig. 34.8). At this point in the operation, specific anatomic landmarks are evaluated, including the lateral edge of the rectus, the conjoined tendon, the pubic tubercle, the shelving portion of the ilioinguinal ligament, and the posterior wall of the inguinal canal [3]. The cord is elevated from the posterior wall and retracted inferiorly. The posterior wall is inspected for any defects (Fig. 34.9). In addition, the rectus abdominus insertion is carefully inspected for the presence of any tearing, laxity, or attenuation.

Fig. 34.7

Penrose around spermatic cord. Integrity of posterior wall and rectus insertion evaluated

Fig. 34.8

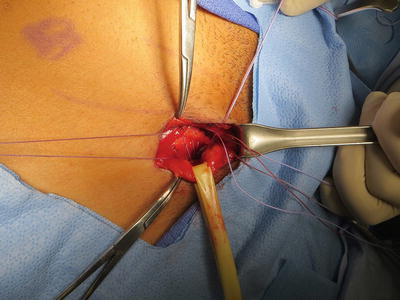

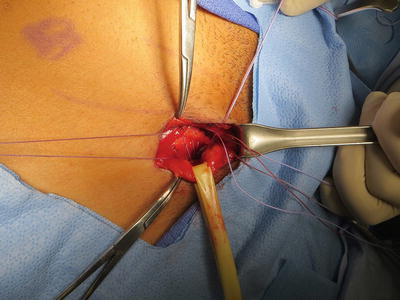

Suture approximating rectus abdominus to the pubic tubercle periosteum

Fig. 34.9

Rectus approximated to Cooper’s ligament, and interface of conjoined tendon/rectus brought to shelving portion of ilioinguinal ligament, with reinforcing sutures laterally from conjoined tendon to shelving portion

The insertion site of the rectus abdominus on the pubic tubercle is prepared to a bleeding bony bed. The inferolateral edge of the rectus is then brought down to the tubercle periosteum with 1–2 stitches of Orthocord (Depuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN, USA) (Fig. 34.9). The tendon edge is next approximated to Cooper’s ligament with another stitch, followed by a third stitch brining the interface of the conjoined tendon and rectus down to the shelving portion of the ilioinguinal ligament. Finally, one to two additional stitches are placed laterally and used to reinforce the conjoined tendon to the shelving portion (Fig. 34.10). Typically, a total of five stitches are used and once in place are sequentially tied down. Once the sutures are tied, appropriate re-tensioning of the rectus is appreciated through palpation.

Fig. 34.10

The axial oblique T2-weighted sequence shows the increased signal intensity at the left rectus abdominus–adductor longus aponeurosis consistent with a tear

The spermatic cord is allowed to resume its native position, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique is closed with running 2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ), followed by closure of the subcutaneous tissues with 2-0 Vicryl in an interrupted fashion. The skin is re-approximated with a 4-0 monofilament, using a running subcuticular technique. Local anesthetic is used on the incision site and also to perform an ilioinguinal nerve block to help decrease postoperative pain. Sterile dressings are then applied.

Our surgical procedure is performed as an outpatient procedure. Postoperatively, patients are immediately weight-bearing as tolerated. Patients return for their initial postoperative visit and wound check approximately 10 days postoperative. At this time, gentle hip range of motion and closed-chain exercises are encouraged, followed by gradual progression to core exercises by week 4. Return to sporting activity is anticipated by postoperative week 6.

Our institution’s multidisciplinary team treatment approach is based on the belief that the chief pathology involved in athletic pubalgia is the insertion of the rectus abdominus. It has been our experience that this region is most often attenuated, and that direct reinsertion of the tendon back to its pubic insertion site has provided excellent and consistent results. Another important aspect of our surgical technique is the widened reinsertion of the rectus tendon. We believe that the success of operative treatment is a result of spreading of the muscular forces of the rectus insertion over a wider insertion area on the pubic bone, thereby decreasing the concentrated forces applied through the tendon attachment.

Cases

Case 1: Athletic Pubalgia, Rectus Abdominus Tear

History/Exam

A 48-year-old male hockey centerman presented to the orthopedic clinic with a history of intermittent right groin and hip pain for 5 years, occurring during hockey season. It typically resolved with rest and physical therapy. Despite extensive conservative treatment, including rest and physical therapy, he underwent bilateral laparoscopic inguinal direct wall hernia repair, utilizing mesh. He continued to have right groin pain, despite postoperative physical therapy. Postoperatively, he underwent a diagnostic/therapeutic injection ultrasound-guided injection along the right side of the pubic symphysis, utilizing a peppering technique. He reported minimal improvement following this injection. He was referred to the orthopedic clinic.

On physical examination, the patient is noted to have a non-antalgic gait. The patient is noted to have tenderness to palpation at the pubic symphysis area and in the lower right rectus region. He has full range of motion of his right hip. He has no pain elicited with passive right hip flexion/adduction/internal rotation (FADIR test). The patient’s right lower abdominal pain is worsened with resisted right hip flexion as well as with performing a sit-up. He has no palpable direct or indirect hernias present.

Imaging

Plain radiography did not demonstrate any significant pathology. Specifically, there was no evidence of right hip degenerative changes or evidence of findings consistent with femoroacetabular impingement.

MRI of the pelvis was then obtained. The axial oblique T2-weighted sequence (Fig. 34.10) shows the increased signal intensity at the left rectus abdominus–adductor longus aponeurosis consistent with a tear. In addition, the tear at the aponeurosis was visualized on the sagittal T2-weighted fat-suppressed image (Fig. 34.11).