Asif Saifuddin

Bone Marrow Disorders

Haematological Neoplasms

Chapters 71 and 72 deal with a variety of blood-related disorders that have a major influence on imaging of the skeletal system. The 2008 World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of myeloproliferative neoplasms is complex and includes a variety of conditions of differing malignant potential.1 Only those that have significant radiological manifestations in the skeletal system will be discussed.

Primary Myelofibrosis2

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm characterised by stem cell-derived clonal myeloproliferation resulting in bone marrow fibrosis, anaemia, splenomegaly and extramedullary erythropoiesis. The diagnosis is based on bone marrow morphology, showing evidence of fibrosis, and is supported by a variety of genetic abnormalities.

Clinical Features

It affects men and women equally, with an age range of 20–80 years (median age 60 years). The disorder presents insidiously with weakness, dyspnoea and weight loss due to progressive obliteration of the marrow by fibrosis or bony sclerosis, which leads to a moderate normochromic normocytic anaemia. Extramedullary erythropoiesis takes place in the liver and spleen, which become enlarged in 72 and 94% of cases, respectively, but is also reported in lymph nodes, lung, choroid plexus, kidney, etc. The natural history is one of slow deterioration, with death typically occurring 2–3 years after diagnosis. Progression to leukaemia is also a feature.

Radiological Features3

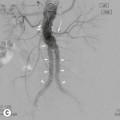

Bone sclerosis is the major radiological finding, being evident in approximately 30–70% of cases. Typically, this is diffuse (Fig. 71-1) but occasionally patchy, occurring most often in the axial skeleton and metaphyses of the femur, humerus and tibia. Sclerosis is due to trabecular and endosteal new bone formation, resulting in reduced marrow diameter. In established disease, lucent areas are due to fibrous tissue reaction. Periosteal reaction occurs in one-third of cases, most often in the medial aspects of the distal femur and proximal tibia. The skull may show a mixed sclerotic and lytic pattern.

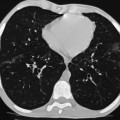

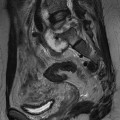

MRI appearances vary depending upon the tissue contained in the marrow. Typically, the hyperintensity of marrow fat is replaced on both T1- and T2-weighted (T1W, T2W) sequences by hypointensity, which may be diffuse or heterogeneous (Fig. 71-2). Additional features include arthropathy due to haemarthrosis and secondary gout, occurring in 5–20% of cases. Also, infiltration of the synovium by bone marrow elements may result in polyarthralgia and polyarthritis. Leukaemic conversion may manifest radiologically by the development of an extraosseous soft-tissue mass (Fig. 71-3).

Radiological differentiation between other causes of increased bone density may be difficult, but the presence of anaemia and splenomegaly should suggest the diagnosis in this age group. Radiological differential diagnosis includes osteopetrosis, fluorosis, mastocytosis, carcinomatosis and adult sickle cell disease (SCD).

Systemic Mastocytosis4

Systemic mastocytosis represents a clonal disorder of mast cells, which is classified according to the WHO 2008 system into indolent mastocytosis, systemic mastocytosis with an associated haematological non-mast cell disorder, aggressive systemic mastocytosis and mast cell leukaemia. The majority of cases are associated with a pathological increase in the number of mast cells in both skin and extracutaneous tissues, although bone marrow involvement can occur without skin disease.

Clinical Features

The condition presents in the fifth to eighth decades with equal frequency in men and women. Bone marrow involvement is present in approximately 90% of cases and is often asymptomatic, but may produce thoracic and lumbar spinal pain and arthralgia. The condition may be associated with myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative neoplasia, leukaemia and lymphoma. The prognosis is variable.

Radiological Features

Imaging, including radiography, scintigraphy, bone densitometry, CT and MRI, plays a role in the diagnosis, staging and monitoring of the disease. Skeletal changes are due to both the direct effect of mast cells and the indirect effect of secreted mediators such as histamine, heparin and prostaglandins. They include both osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions, which may be either diffuse or focal. Small (4–5 mm) lytic lesions may be surrounded by a rim of sclerosis and are most commonly seen in the spine, ribs, skull, pelvis and tubular bones. Diffuse osteopenia is a common pattern (Fig. 71-4), most commonly involving the axial skeleton, and may be complicated by pathological fracture in 16% of cases. Differential diagnosis includes cystic osteoporosis, Gaucher’s disease, myeloma, hyperparathyroidism or thalassaemia.

Osteosclerosis produces trabecular and cortical thickening with reduction of the marrow spaces (Fig. 71-5), and multifocal sclerotic lesions simulating osteoblastic metastases (Fig. 71-6). Both Multidetector CT (Fig. 71-7) and MRI are more sensitive than radiography in the identification of marrow involvement. In mild cases, MRI may be normal. Otherwise, there is a generalised reduction of T1W signal intensity (SI), with variable T2W and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) SI, depending upon the degree of associated marrow fibrosis. Sclerotic lesions appear hypointense on all pulse sequences. The role of FDG-PET is unclear.

Leukaemia5

Leukaemia accounts for approximately 25–33% of all childhood malignancy, the vast majority being the acute form. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL) accounts for 75%, acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) for 20% and other types for 5% of cases. Chronic leukaemias predominate in adults but sometimes terminate in an acute blastic form. While radiographic demonstration of bone lesions in children is relatively common, skeletal lesions in adults tend to be uncommon and focal, often simulating metastases.

Clinical Features

ALL usually presents in children at 2–3 years of age, while AML is most commonly seen in the first 2 years of life, and then also in adolescence. The acute disease is often insidious, with non-specific malaise, anorexia, fever, petechiae and weight loss. Limb pain and pathological fracture are common. Bone pain at presentation is five times more common in children than adults, being reported in over 33% of cases.

Adults are most commonly affected by ALL and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). Most skeletal lesions in adults affect sites of residual red marrow, the axial skeleton and proximal ends of the femora and humeri. Chronic lymphatic leukaemia (CLL) is a disease of the elderly, characterised by enlargement of the spleen and lymph nodes with skeletal involvement being rare, except as a terminal event.

Radiological Features

Radiological evidence of bone involvement in acute paediatric leukaemia is reported in approximately 40% at the time of presentation, the incidence of the various features being as follows: osteolysis (13.1%), metaphyseal bands (9.8%), osteopenia (9%), osteosclerosis (7.4%), permeative bone destruction (5.7%), pathological fracture (5.7%), periosteal reaction (4.1%) and mixed lytic–sclerotic lesions (2.5%).6 However, such changes will be seen in up to 75% of children during the course of their disease.

Diffuse osteopenia is reported in 16–41% of cases and either may be metabolic in aetiology due to protein and mineral deficiencies or may be related to diffuse marrow infiltration with leukaemic cells. The effects of corticosteroids and chemotherapy also contribute to osteoporosis. Compression fractures occur in association with osteopenia of the spine (Fig. 71-8), while approximately 1% of children treated for leukaemia develop osteonecrosis.

Metaphyseal lucent bands primarily affect sites of maximum growth, such as the distal femur, proximal tibia and distal radius, but other metaphyses and the vertebral bodies are affected later. They are typically 2–15 mm in width (Fig. 71-9). These changes are non-specific, with the differential diagnosis including generalised infection, although this is more common in infancy. In children over the age of 2 years, leukaemia is more likely.

More extensive involvement results in diffuse, permeative bone destruction (Fig. 71-10) similar to the spread of highly malignant tumours such as Ewing sarcoma. The cortex becomes eroded on its endosteal surface and may ultimately be destroyed. The permeative pattern is reported in 18% of leukaemic children and may indicate a poor prognosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree