14 Interventional Ultrasound It was shown in the Intermediate Course that the most common breast lesions display typical features that, in the majority of cases, allow them to be diagnosed from imaging findings. Cysts are a frequent cause of pain or palpable nodules that prompt women to seek medical attention, and can be reliably diagnosed with ultra-sound. If the mammographic findings are not suspicious, there is no need for further evaluation. Nor is it necessary to further evaluate areas of breast firmness that show cyclic variations in patients who have normal sonographic and mammographic findings. Solid circumscribed lesions present a more difficult challenge. Although many benign and malignant lesions can be distinguished by their sonographic and mammographic features, some lesions cannot be reliably differentiated. These problems were addressed in the sections on differential diagnosis in the Intermediate Course. It is important to understand that many solid masses cannot be characterized confidently on the basis of imaging findings alone. It would be inappropriate to evaluate all these lesions by surgical biopsy, as the large number of operations for benign lesions would result in an excessive financial burden as well as physical and emotional distress. The advantage of nonsurgical interventional procedures is that they can establish the identity of an indeterminate lesion accurately with minimal effort and expense. This can be accomplished by means of various percutaneous techniques. In the past, only breast masses that were palpable were evaluated by percutaneous needle biopsy. These procedures, guided by palpation, were done as part of a “triple test” consisting of physical examination, mammography, and aspiration cytology (Hernan et al., 2003). However, manually guided aspiration was a blind technique that had a relatively high failure rate of 15–20%, because it was uncertain whether the sample came from the lesion itself or from tissue outside it. Accuracy was improved by the introduction of stereotactic biopsy. However, this procedure can be time-consuming, requires ionizing radiation and extra mammographic views, and also requires the patient to be immobilized in a prone or seated position. Ultrasound guidance provides a rapidly performed, more comfortable, real-time alternative. As a result, ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsies are now the procedure of choice for tissue sampling of sonographically detectable breast lesions. Imaging-directed needle procedures are valuable not only for the histologic or cytologic sampling of indeterminate lesions but also for the aspiration of cysts and fluid collections, such as abscesses, that are painful or present as indeterminate nodules. Ultrasound can also be used for preoperative localization and to determine whether or not a nonpalpable mass has been included in the surgical specimen (Table 14.1). In cases where ultrasound findings are equivocal and mammograms show a suspicious lesion, usually associated with suspicious microcalcifications, the lesion should be localized preoperatively under stereotactic mammographic guidance or using an alphanumeric grid. The specimen should also be radiographed. Research is currently being conducted into use of ultrasound to guide therapeutic procedures for breast cancer. Various means of tumor destruction—including radiofrequency, cryoablation, and high-frequency ultrasound (HIFU)—are under study, and ultra-sound guidance for placement of balloon catheters for accelerated partial breast irradiation has been employed for several years (Table 14.2). The usage of ultrasound-guided needles for fine-needle aspiration, core biopsy, or preoperative localization should be optimized to ensure accurate needle placement and avoid complications. The reflective and refractive properties of ultrasound are an important consideration. As explained in the Basic Course, structures that are perpendicular to the ultrasound beam are optimally visualized. If the beam encounters the structure at an oblique angle, the image is poorly rendered, and a structure may not be visualized at all if it is parallel to the beam. The same geometric principle holds true for depiction of the needle: its type and gauge are less important than its angle in relation to the image plane.

Clinical Significance

Needle Insertion Technique

|

|

In some ultrasound-guided needle procedures, the target lesion is displayed at the edge of the image to minimize the distance between skin and lesion that the needle must traverse. The needle is then inserted adjacent to the transducer and advanced toward the lesion in an anteroposterior direction (Fig. 14.1). Most needle guides that attach to transducers are designed for anteroposterior insertion. Although this approach may be of benefit for presurgical needle localizations and cyst aspiration, the problem with this technique for breast procedures is that the needle is visualized poorly, if at all, because of its obliquity to the image plane (Fig. 14.2 a, b). It should also be considered that when breast ultra-sound is carried out in the supine patient, the pressure from the transducer usually results in a tissue thickness of only 2–3cm between the transducer and chest wall. When the needle is inserted anteroposteriorly at a steep angle, there is a risk of passing through the intercostal space and entering the pleural cavity or pericardial sac. To avoid a possible life-threatening complication, automated core-biopsy devices should never be directed perpendicular to the chest wall; the angle of insertion should be shallow or parallel to the face of the transducer and to the chest wall, always under direct ultrasound visualization.

An anteroposterior approach perpendicular to the chest wall makes it difficult to monitor the needle position and increases the risk of complications.

It is better to position the transducer so that the lesion, in view in its entirety, is 1–2 cm from the edge of the image. The convexity and compliance of the breast, along with careful positioning of the patient, usually make it possible to position the transducer roughly parallel to the chest wall while inserting the needle from the periphery in a nearly horizontal direction, directing it approximately parallel to the transducer face and chest wall (Figs. 14.3, 14.4 a, b). In this chest-wall parallel approach, the needle returns high specular echoes and can be monitored throughout the procedure (Figs. 14.2a, b; 14.5a, b). Even if the needle misses the lesion, there is no risk of serious injury because the needle cannot enter the pleural cavity.

If the needle is inserted at the center of the transducer and advanced at a steep angle toward the tumor, passing through the image plane, the operator sees only a punctate cross section of the needle shaft and has no idea where the needle tip is located (Fig. 14.6). The needle itself is not even visible until it enters the image plane. If the target is missed, it is often necessary to withdraw and reintroduce the needle. Also, the anteroposterior approach poses a risk of injury to deeper structures. As a result, beginners in particular should avoid using this technique. It should never be used with automated core-biopsy guns because of the risk of complications.

The best technique, illustrated in Figures 14.2–14.4, istoinsert the needle horizontally along the image plane of the transducer. It is important to keep the needle’s path straight below the center of the transducer while directing it along the image plane (Figs. 14.4, 14.7). Some linear transducers have a vertical seam, visible from the short end of the transducer, that joins the two halves of the probe housing. This vertical seam can be used to imagine the path of the ultrasound beam as it emerges in a thin sheet from the transducer. The goal would be to keep the needle within the expected path of this beam, without angling to the left or right. If the examiner inserts the needle off-center from the transducer and tries to advance it obliquely toward the lesion, the needle will pass through, rather than along, the image plane. Part of the needle will be visible on the monitor but usually not the tip, which can easily miss the target.

Fig. 14.1 Cave: Faulty technique of needle insertion. The needle is inserted anteroposteriorly toward the chest wall. The needle is difficult to visualize and may penetrate the intercostal space. This technique is hazardous and unreliable, and should never be used for core biopsy.

Fig. 14.2 a, b Ultrasound guidance of needle placement in a breast phantom.

a With an approach parallel to the chest wall along the scan plane, the tip of the needle is clearly visible.

b Anteroposterior insertion creates an unfavorable reflection angle, and the needle is poorly visualized.

Once the appropriate path is selected and the lesion is in view, rapid completion of the biopsy will prevent the need for continual minor readjustment necessitated when the hand moves a few millimeters out of the plane of the lesion. An additional tip for successful performance of these biopsy procedures is the use of just enough gel to enable the target to be seen; the lesion has already been characterized with ultrasound, and the probe will slide away from the area to be sampled if gel is applied liberally. The probe can be stabilized further by holding it near its base, and even more so if the hand rests on sterile gauze placed around one end of the transducer. If the operator unconsciously applies excessive pressure against the breast to prevent slippage of the transducer, visualization of the needle will be diminished even if the appropriate geometry is maintained. One last suggestion is an important one: the operator’s hand and body should make one smooth line as the operator moves his eyes up from the short end of the transducer on the breast to the ultrasound monitor and back again to confirm accuracy of needle passage. The success of the procedure may be compromised if the operator must twist and turn his body to look at the monitor and then again turn away from the monitor to look back at his hands and the needle.

Fig. 14.3 Correct needle insertion technique. The needle is inserted from the periphery and directed approximately parallel to the transducer face and chest wall. This improves ultrasound visualization of the needle and avoids the risk of deep injury.

Fig. 14.4 a–c Practicing fine-needle aspiration in a breast phantom.

a The needle should be inserted from the periphery at a shallow angle.

b The needle is placed below the center of the transducer and advanced straight along the image plane.

c If inserted off-center, the needle passes through the image plane, and the position of the needle tip cannot be monitored.

Fig. 14.5 a, b Fine-needle aspiration in a breast phantom.

a The target lesion is positioned about 1–2 cm from the edge of the image. Its depth (1 cm) can be read from a scale at the edge of the image.

b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

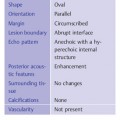

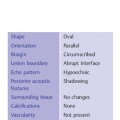

Cyst aspiration (for pain or a firm nodule)

Cyst aspiration (for pain or a firm nodule) Investigation of indeterminate solid masses

Investigation of indeterminate solid masses Preoperative histologic confirmation

Preoperative histologic confirmation Establishing a diagnosis prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Establishing a diagnosis prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy Preoperative localization of nonpalpable masses

Preoperative localization of nonpalpable masses Localization of small lesions in the surgical specimen

Localization of small lesions in the surgical specimen Fine-needle aspiration cytology or cyst aspiration

Fine-needle aspiration cytology or cyst aspiration Spring-activated core biopsy

Spring-activated core biopsy Vacuum-assisted large core biopsy

Vacuum-assisted large core biopsy Preoperative wire localization or dye injection

Preoperative wire localization or dye injection