Antenatal factors

Previous PPH

Previous caesarean delivery

Age > 40 years

Obesity BMI > 30

Multiple pregnancy

Fibroid uterus

Anaemia (Hb < 9 g/dl)

Antepartum haemorrhage

Polyhydramnios

Preeclampsia/eclampsia

Pregnancy induced hypertension

Abnormal placental localisation (praevia and accreta)

Baby > 4 kg in current pregnancy

Intrapartum factors

Induction of labour

Pyrexia in labour

Preeclampsia/eclampsia

Prolonged first stage of labour >12 h

Uterine hyperstimulation

Prolonged second stage of labour (>2 h in a primpara and >1 h in a multipara)

Episiotomy

Instrumental delivery

Caesarean delivery

4 Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage

Once excessive bleeding is recognised, management of the woman involves several parallel components: stopping the bleeding (depending on cause), fluid resuscitation and communication with relevant senior obstetric, anaesthetic and haematological teams as well as the patient and her family. Resuscitation of the patient with fluids, blood and blood products is indicated primarily on clinical signs and symptoms as well as on coagulation results. This takes place simultaneously with trying to identify and arrest the cause of the bleeding (Table 2). The most common cause of primary PPH is uterine atony, but other causes such as retained placental tissue, uterine rupture, uterine inversion, vaginal or cervical lacerations, abnormal placentation or haematomas or extra-genital bleeding must also be considered and excluded. So traditionally, the causes for postpartum haemorrhage usually relate to one of the ‘four Ts’: Tone, Tissue, Trauma and Thrombin.

Table 2

Management of primary PPH (Adapted from Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2009)

Mechanical measures | Rub up a contraction |

Empty the bladder by insertion of urinary catheter | |

Examine the vagina to exclude vaginal and cervical lacerations | |

Bimanual uterine compression | |

Evacuation of the uterus (manual removal of placenta, examination under anaesthetic or evacuation of retained products) | |

Pharmacological measures | Oxytocinon 5 units by slow i.v. injection |

Ergometrine 0.5 mg by slow i.v. or i.m. injection (contra indicated in women with hypertension unless exsanguinating) | |

Oxytocinon infusion | |

Carboprost 0.25 mg by i.m. injection repeated at 15 min intervals up to eight doses (contraindicated in women with asthma unless exsanguinating) | |

Misoprostol 1000 mcg rectally | |

Tranexamic acid | |

Recombinant factor VIIa | |

Surgical measures | Repair of perineal or vaginal trauma |

Control of surgical bleeding at caesarean | |

Intrauterine balloon tamponade | |

Haemostatic brace sutures | |

Bilateral ligation of uterine arteries | |

Bilateral ligation of internal (hypogastric) arteries | |

Selective arterial embolisation | |

Hysterectomy—must be considered early once surgical measures started |

When haemorrhage continues then second-line therapies must be initiated as simultaneous resuscitation of the patient continues. Second-line therapies encompass a number of surgical measures as outlined in Table 2.

At laparotomy, surgical interventions include compression sutures, ligation of the internal iliac vessels and hysterectomy. The recourse to emergency hysterectomy is not a decision that is made lightly as it removes future childbearing possibility. However, it must not be delayed; this is a common criticism in mortalities. The decision is usually made as a life-saving measure and in conjunction with another senior obstetric or gynecological colleague and the procedure is often performed jointly.

4.1 Tamponade Techniques

One of the first, and technically easiest, second-line measures to control bleeding from an atonic uterus is insertion of a hydrostatic uterine balloon catheter into the uterine cavity followed by inflation of the balloon with 300–500 mL of saline to exert a tamponade effect on the uteroplacental vessels. In modern obstetric practice, this has superseded the previous method of packing the uterus with large gauze swabs. Various catheter devices exist e.g. Sengstaken–Blakemore oesophageal catheter, Rusch and Bakri balloon catheters. Various authors have reported success in stopping PPH and thus averting a hysterectomy. The general success rate is around 78 % (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2009).

4.2 Uterine Compression Sutures

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show various compression sutures. The brace compression suture was first described by B-Lynch et al. (1997). The technique requires laparotomy and a bimanual compression test performed prior to its insertion. If the compression test is ineffective in reducing bleeding then the B-Lynch suture is unlikely to be successful. The principle of action is that the suture exerts a direct compression effect on the myometrium to promote uterine tone without interfering with the uterine blood supply. Since 2007, several other variations of uterine compression suture techniques have been described such as the Cho square sutures, the Hayman suture and the Pereira suture (Cho et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2002; Bhal et al. 2005; Pereira et al. 2005; Nelson and Birch 2006; Ouahba et al. 2007). A 91.7 % cumulative success rate in controlling PPH has been reported for a combination of the various techniques (Doumouchtsis et al. 2007).

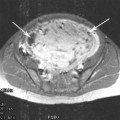

Fig. 1

The B-Lynch Suture. Figure reproduced from A Textbook of Postpartum Haemorrhage, a comprehensive guide to evaluation, management and surgical intervention. Edited by Christopher B-Lynch FRCS, FRCOG, D. Univ., Louis Keith MD, PhD Andre Lalonde MD, FRCSC, FRCOG and Mahantesh Karoshi MBBS, MD. www.glowm.com/pdf/PPH_2nd_edn_Chap-51.pdf

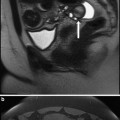

Fig. 2

The Cho multiple square sutures—compressing anterior to posterior uterine walls. Figure reproduced from A Textbook of Postpartum Haemorrhage, a comprehensive guide to evaluation, management and surgical intervention. Edited by Christopher B-Lynch FRCS, FRCOG, D. Univ., Louis Keith MD, PhD Andre Lalonde MD, FRCSC, FRCOG and Mahantesh Karoshi MBBS, MD. www.glowm.com/pdf/PPH_2nd_edn_Chap-51.pdf

Fig. 3

The Hayman uterine compression suture. Figure reproduced from A Textbook of Postpartum Haemorrhage, a comprehensive guide to evaluation, management and surgical intervention. Edited by Christopher B-Lynch FRCS, FRCOG, D. Univ., Louis Keith MD, PhD Andre Lalonde MD, FRCSC, FRCOG and Mahantesh Karoshi MBBS, MD. www.glowm.com/pdf/PPH_2nd_edn_Chap-51.pdf

Advantages of uterine compression sutures include simplicity in application, short operating time (5–15 min), but importantly preserving the uterus and the possibility of a future pregnancy. Complications are few, but may arise immediately postoperatively or up to 2 years. There have been no reported deaths arising from complications, but case reports included pyometra, ischaemic uterine necrosis, uterine suture erosion and uterine synechiae, with acute or chronic inflammation and uterine necrosis being the most widely reported complications. Cases of successful pregnancies without any significant complications for mother and baby have been reported in the literature. The time of subsequent conception varies from 3 months to 3 years. No cases of subfertility requiring assisted conception have been reported (Fotopoulou and Dudenhausen 2010; Mallappa Saaroja et al. 2010).

4.3 Internal Iliac Artery Ligation

The traditional surgical means of uterine conservation is step-wise devascularisation of the blood supply to the uterus. The uterine vessels and/or the ovarian vessels may be ligated if the operator is confident that ligating that branch alone will stop the haemorrhage, but this is unlikely given the substantial collateral pelvic circulation. Thus, bilateral ligation of the internal iliac arteries is performed, as it has been shown to significantly reduce the pelvic pulse pressure and facilitate haemostasis. Substantial collateral pelvic circulation means that blood supply to the pelvic viscera is not compromised.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree