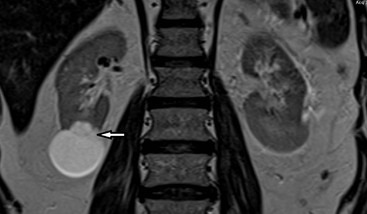

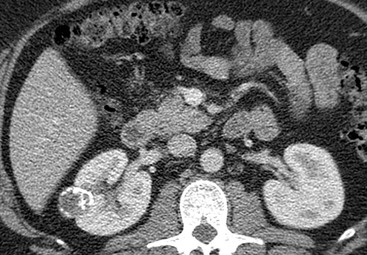

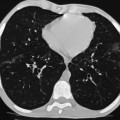

Giles Rottenberg, Zaid Viney The plain abdominal radiograph (KUB—kidneys, ureters, bladder) is rarely used to diagnose a renal mass. Loss of the psoas margin or displacement of retroperitoneal fat may suggest the presence of one, as may an opacity projected over the renal outline, or a loss of the renal outline. Central calcification within a renal mass is more suggestive of malignancy than peripheral calcification (87 vs 20–30%). Intravenous urography (IVU) is a relatively insensitive method for detecting renal masses, particularly if they occur centrally rather than peripherally; cross-sectional techniques are a more appropriate method for investigating a patient with a suspected renal mass. Differentiation between a definite mass and an anatomical variant that simulates a mass (pseudotumour) can be made using radionuclide imaging, although this is rarely useful in practice. Ultrasound (US) is usually the first method for evaluating a patient for a renal mass and is the most appropriate technique for evaluating an abnormal IVU. Ultrasound is ideally suited for children, pregnant women and patients with renal impairment. Ultrasound can reliably differentiate solid masses from simple cysts, which are the most common space-occupying lesions in the kidney. A lesion that appears solid on ultrasound, or demonstrates any suspicious features, merits further analysis with CT or MRI. Ultrasound is less accurate in staging renal cell carcinoma than computed tomography (CT) or MRI. It is poor at demonstrating lymph node disease, skeletal or lung metastases. Computed tomography (CT) is still the Investigation of choice for evaluating and characterising solid renal masses. It can accurately assess ‘pseudomasses’ (see Fig. 36-1) and other anatomical variants and can provide attenuation values that can confirm the presence of fluid in cysts or fat in angiomyolipomas. As CT can delineate accurately the perinephric space and the retroperitoneum, it is useful in the diagnosis of complicated renal sepsis and the assessment of the extent of haemorrhage; it can also identify tumour recurrence after radical nephrectomy. Accurate analysis of renal masses requires the use of intravenous contrast medium. The continued development of multislice CT has improved the detection, characterisation and staging of renal tumours and allows high-quality multiplanar imaging of the kidneys, which is useful for evaluating small areas of enhancement and for presurgical planning. With the increased use of laparoscopic, robotic and nephron-sparing surgery, it is vitally important to be able to review the coronal and sagittal images with surgical colleagues to decide upon appropriate management. Unenhanced CT images are essential for identifying calcification and allow true evaluation of enhancement following IV contrast. Corticomedullary phase (25–40 s post-IV contrast administration) imaging is helpful in demonstrating normal variants, pseudotumours, tumour vascularity and the renal vein. The nephrographic phase (90–100 s post-IV contrast administration) is best for the detection of central renal masses, as the medulla is optimally enhanced and small medullary lesions are better visualised.1,2 For optimal lesion detection and characterisation, images should be obtained in both phases; however, if only one phase is to be used, to reduce radiation dose, it should be the nephrographic phase. If surveillance imaging of a lesion is to be undertaken, the single optimal phase for detection of the mass can be used rather than repeating a three-phase examination. The ability of MRI to characterise renal masses has improved with the development of phased-array multicoils, fast breath-hold imaging and the use of Gd-DTPA contrast enhancement. Protocols vary widely but usually include pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted images with and without fat suppression. The coronal and sagittal planes are helpful for evaluating the extent of lesions. MR angiography can demonstrate the renal arteries and veins, and the inferior vena cava. MRI can be used as an alternative to CT for detection and surveillance of masses, although this depends upon local resources, and availability of equipment. Many radiologists prefer to use CT for the initial evaluation of renal masses as it is such a reliable technique, and easier to interpret than MRI. There has been recent interest in the use of diffusion-weighted imaging for the characterisation of renal masses. Malignant tumours are associated with a significantly reduced analog-to-digital converter (ADC) value3,4 compared to benign lesions, although the utility of this technique is not definitively confirmed at present and not widely practised outside the research setting. Simple renal cysts and angiomyolipomas have characteristic appearances, but the signal from most other masses is nonspecific. MRI is an alternative to CT in patients with renal insufficiency or severe previous reactions to contrast medium. MRI is superior to CT in differentiating benign thrombus from tumour thrombus and in identifying its extent. MRI is ideally suited for monitoring patients who have a genetically increased risk of renal malignancy, such as von Hippel–Lindau disease, who require repeated imaging for surveillance. MRI is no more specific than CT at differentiating malignant from reactive lymphadenopathy, although the development of tissue-specific agents might alter this in the future. MRI is a more lengthy and complex investigation than CT. The role of MRI has reduced with the development of multislice CT, which allows the production of reliable and high-quality multiplanar reconstructions. Renal arteriography is seldom used to diagnose or characterise a renal mass as the necessary information is usually provided by cross-sectional imaging. Angiography can play a role in preoperative embolisation of very vascular tumours immediately before partial nephrectomy. CT or MR angiography is usually sufficient to provide a road map for surgery, and to identify the size, number and position of renal vessels. Percutaneous aspiration of renal cysts is indicated in the investigation of an indeterminate cystic renal mass to diagnose an abscess or an infected cyst. Fluid obtained at aspiration should be sent for cytological examination, although negative cytology does not exclude malignancy; this applies particularly in some cystic renal cell carcinomas, in which malignant disease is confined to the wall of the lesion. If the fluid is found to be turbid, microbiological examination should also be performed. Needle biopsy of a cyst wall can be performed to improve the diagnostic yield although there are small but potential risks in this setting including seeding of tumour and false-negative diagnosis.5 Biopsy is used to confirm the histology of a renal mass in patients with underlying non-renal malignancy or radiological features suggestive of lymphoma. Biopsy is also used to confirm the presence of malignancy before radiofrequency or cryoablation of a renal mass. Histological techniques have improved over the past 10 years and are more reliable at classifying a renal mass and differentiating between oncocytoma and renal cell carcinoma. In patients with significant other comorbidity, this may significantly alter the management of an asymptomatic renal mass. Biopsy should also be considered in bilateral masses to characterise whether the lesions represent multifocal oncocytoma or papillary tumour. This information may make such lesions suitable for attempted nephron-sparing surgery even if potentially suboptimal for this approach. A number of non-neoplastic tumours must be differentiated from renal cell carcinoma. Fetal lobulation occurs as a result of incomplete fusion of the fetal lobules, which results in a lobulated contour to the lateral border of the kidney occurring between the underlying calices. Dromedary humps are bulges occurring on the lateral side of the left kidney. Many of these pseudomasses can be identified with ultrasound but occasionally further imaging is required. This is usually achieved with CT or MRI, although scintigraphic techniques can be used. This is the commonest form of cystic disease and is seen with increasing frequency with advancing age. Autopsy studies have demonstrated a prevalence of almost 50%.The cysts are frequently multiple and occur in various sizes. On ultrasound examination renal cysts appear as anechoic, well-defined masses, with thin walls and good through transmission of sound. On CT, a simple cyst usually appears as a well-defined rounded mass with an attenuation value of 0–20 HU, with an imperceptible wall and no enhancement after injection of contrast medium. The MRI appearance of a simple renal cyst is characterised by a sharply demarcated, homogeneous, hypointense mass on T1-weighted images, which becomes uniformly hyperintense on T2-weighted images and shows no enhancement following contrast medium administration on T1-weighted images. A classification of cystic lesions was suggested in 1986 by Bosniak, based upon CT characteristics, and is used to guide management.7 Class I is a simple benign cyst. Class II cysts have one or more thin septa running through them (<1 mm), thin areas of mural calcification or fluid contents of increased attenuation; they do not enhance following injection of contrast medium and are benign (see Figs. 36-2–36-4). These two categories of cysts are benign, and do not require surgery or radiological follow-up. Class III cysts are more complicated and contain thickened septa, nodular areas of calcification or solid non-enhancing areas. Mural enhancement can be seen in class III lesions, which are indeterminate for malignancy and should be biopsied or surgically explored. Less than 50% of these will turn out to be malignant, although there can be significant interobserver variation in how such cysts are classified. Class IV cystic masses are clearly malignant, with solid enhancing nodules and should be treated accordingly. A subcategory, IIF, has been suggested for lesions with multiple class II features, and these require follow-up for up to 5 years to exclude malignancy (see Fig. 36-5). Surveillance of these lesions may demonstrate growth or change in calcification, but it is the development of enhancing soft tissue that should upgrade the cystic lesion and result in surgical treatment. Category IIF lesions are large (>3 cm) hyperdense cysts or hyperdense cysts that are totally intrarenal. A simple benign cyst on ultrasound or CT requires no further investigation or follow-up. If there is wall thickening or the contents of the cyst are not of water density, the lesion is indeterminate. Haemorrhage or infection may result in cyst fluid of high attenuation but, unlike tumours, such lesions do not enhance following the administration of contrast medium. It is usually necessary to obtain a pre-contrast CT to adequately assess a rounded homogeneous lesion on a post-contrast CT that is not of water density to exclude low-grade enhancement signifying a renal mass, e.g. papillary tumour, rather than a benign cyst. Ultrasound is helpful if the hyperdense mass satisfies the sonographic criteria of a benign simple cyst. Thick and irregular mural calcification can be seen with both cystic renal cell carcinomas and complicated renal cysts.8 CT attenuation values in both lesions may be identical. Cystic renal cell carcinomas (especially papillary cystadenocarcinomas) may have fluid-range densities, while benign haemorrhagic cysts may have attenuation values much higher than those acceptable for benign cysts. These occur in the renal sinus and frequently cause distortion, but rarely obstruction, of the renal collecting system. Peripelvic cysts are of lymphatic origin, whereas parapelvic cysts are renal serous cysts arising from the renal parenchyma that is present in the sinus. Although parapelvic cysts may be evaluated satisfactorily using ultrasound, peripelvic cysts can occasionally lead to confusion with hydronephrosis, as they track along the renal infundibula. Careful examination should demonstrate that the apparently dilated infundibula do not connect to a dilated renal pelvis. If necessary, urography or CT in the pyelographic phase is usually confirmatory. This is an autosomal dominant hereditary condition which affects many organs in addition to the kidneys. Although it has 100% penetrance, it has variable expression and does not generally produce symptoms until adult life. Renal cysts are seen in addition to cysts within the liver, pancreas and spleen, although hepatic failure does not tend to occur despite extensive infiltration. Coexisting aneurysms of the circle of Willis are seen in 10–16% of patients in autopsy series and as many as 41% of patients undergoing cerebral angiography. The imaging appearances vary with the severity of the disease. Ultrasound demonstrates cysts in the adolescent or young adult, who is usually not yet clinically symptomatic. CT and MRI are more sensitive and frequently show more cysts than US. Adults presenting with ADPKD usually have enlarged kidneys with numerous cysts of varying sizes. Occasionally, an infected cyst, a hyperdense cyst and, less commonly, a renal neoplasm may coexist with adult polycystic renal disease and the diagnosis becomes somewhat difficult in these cases. MRI may prove to be a useful technique in differentiating between simple cysts, haemorrhagic cysts and neoplasms when the findings on CT and ultrasound are equivocal. Infected cysts can be difficult to diagnose, and aspiration of a dominant or hyperdense cyst may be required for definitive evaluation. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) can be helpful in evaluating for the presence of an infected cyst, and has logistical advantages over white cell scintigraphy in such cases. This is a non-hereditary, congenital, usually unilateral form of renal cystic disease and is one of the commonest causes of an abdominal mass in the newborn. Localised cystic disease is characterised by the presence of multiple cysts seen throughout part, or all, of one kidney (see Fig. 36-6). The aetiology of this disorder is not known. Normal cortex is seen between the individual cysts, which helps distinguish the disease from multicystic dysplastic kidney. The contralateral kidney is usually entirely normal or contains several small cysts, which can help distinguish it from ADPKD, in which multiple cysts of varying size are seen in enlarged kidneys bilaterally. It is equally important to distinguish localised cystic disease of the kidney from multilocular cystic nephroma, which is achieved by the demonstration of normal parenchyma between the cysts. These are rare in most parts of the world and uncommon even in endemic areas. They are thick-walled, mainly intrarenal, and sometimes calcified. Hydatid cysts may present as flank or perinephric masses, which rupture into the collecting system, giving rise to acute flank pain followed by the voiding of hydatid scolices, with or without haematuria. Ultrasound demonstrates a multicystic lesion of mixed reflectivity. Renal abscesses are increasingly uncommon, as urinary tract infection is usually treated early. Most abscesses are due to ascending infection, commonly by Escherichia coli (see Fig. 36-7

Renal Masses

Imaging and Biopsy

Methods of Analysis

Plain Abdominal Radiography

Intravenous Urography

Radionuclide Imaging

Ultrasound

Computed Tomography

MRI

Renal Arteriography

Needle Aspiration and Biopsy

Non-Neoplastic Renal Masses

Pathological Renal Masses

Renal Cysts

Serous Renal Cyst

‘Complicated Cysts’ 6,7

Parapelvic and Peripelvic Cysts

Adult Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

Multicystic Renal Dysplasia

Localised Cystic Disease of the Kidney

Hydatid (Echinococcal) Cysts of the Kidney

Inflammatory Masses

Renal Abscesses

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Renal Masses

Chapter 36