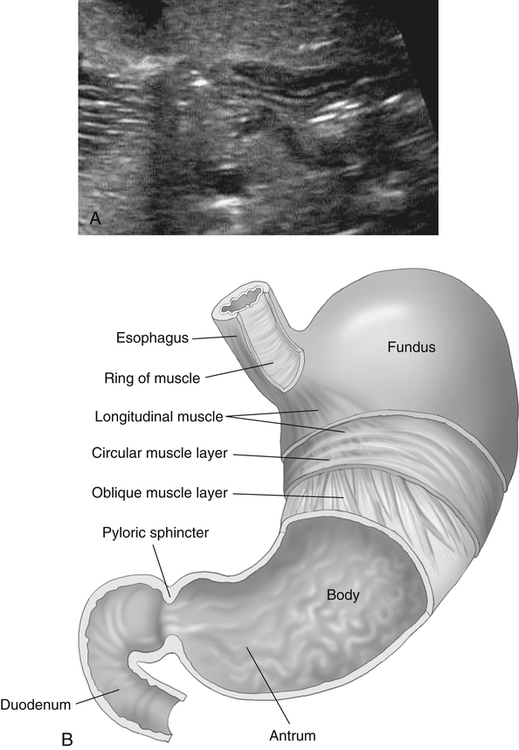

• Describe the epidemiology, anatomy, and pathophysiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. • Explain the clinical presentation, sonographic findings, and treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. • Describe the epidemiology, anatomy, and pathophysiology of intussusception. • Describe the clinical presentation, sonographic findings, and treatment of intussusception. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) has a rate of occurrence of 3 per 1000 infants1,2 and is four to five times more likely to occur in male infants than in female infants.3 IHPS has been reported to have a familial predisposition, resulting in a higher incidence of occurrence in first-born white boys.1,3,4 The symptoms usually begin within 3 to 6 weeks after birth; however, IHPS may infrequently occur in infants 1 week of age up to 5 months of age.1 IHPS is thought to be an acquired condition with unknown cause, although various etiologic theories exist. The most notable of these theories is a possible association with oral administration of the medication erythromycin at an early age.1,2,4 Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the result of hypertrophy of the circular musculature that surrounds the pylorus, which causes constriction and obstruction of the gastric outlet. The pylorus is a tubular structure located on the right side of the stomach. It is the sphincter that connects the stomach with the duodenum of the small intestine. The most common position of the pylorus is about 3 cm to the right of the midsagittal axis at the level of the first lumbar vertebra (Fig. 12-4). Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis can be viewed with real-time imaging of the pylorus muscle preferably 2 to 3 hours after the last meal. A high-frequency linear array probe ranging from 7 to 12 MHz is most commonly used; in older patients, a 3 to 7 MHz curvilinear probe may be necessary. Patients should undergo scanning in the right posterior oblique position (RPO) if possible. The RPO position helps with visualization of the pylorus with use of the fluid-filled stomach as a scanning window. The location of the pylorus can be identified with scanning in a transverse plane along the lesser curvature of the stomach through the left lobe of the liver just to the right of midline. The pylorus lies inferior and to the right of the antrum of the stomach. If the pylorus is not well visualized, the patient may drink some water for display of the gastric lumen. Gastric peristalsis can be seen in real time after the ingestion of approximately 60 to 120 mL of an electrolyte replacement fluid or water. The sonographer should remember to keep a towel handy because an infant is prone to vomiting after ingestion of the fluids. Absent peristalsis and lack of movement of fluid through the pylorus with a thickened AP muscle wall and increased pylorus channel length indicate stenosis. Measurements should be taken to document the size of the muscle. Although measurements may vary slightly between institutions, the most commonly accepted measurements for diagnosing pyloric stenosis include an AP muscle wall thickness of 3.0 mm or more (Figs. 12-5 and 12-6) with a pylorus length of 17 mm or more. A stenotic pyloric channel resembles the sonographic appearance of the cervix in pregnancy and is nicknamed the “cervix sign” (Figs. 12-7 and 12-8). Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis can be dangerous if not diagnosed within several days of the onset of symptoms. Severe dehydration and biochemical disturbances, such as hypokalemic or hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis (Table 12-1), can occur when the condition is untreated.2,3 Patients in whom the hypertrophied pylorus can be reliably palpated by an experienced clinician may not need sonographic evaluation. The use of sonography is best reserved for cases in which the clinical examination results are negative. TABLE 12-1 Laboratory Findings of Gastrointestinal System

Suspect Pyloric Stenosis or Other Gastrointestinal Findings

Pyloric Stenosis

Epidemiology

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

Sonographic Findings

Pathology

Laboratory Findings

Pyloric stenosis

Hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis

Intussusception

Anemia, leukocytosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine