Parkinsonism is a syndrome that features bradykinesia (slowness of the initiation of voluntary movement) and at least 1 of the following conditions: rest tremor, muscular rigidity, or postural instability. Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of vascular parkinsonism (VP) have been proposed, which are derived from a postmortem examination study. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can support this clinical diagnosis with positive imaging findings. Dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography may also be of help to distinguish VP from Parkinson disease and other parkinsonisms.

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a syndrome that features bradykinesia (slowness of the initiation of voluntary movement) and at least 1 of the following conditions: rest tremor, muscular rigidity, or postural instability. In 1929, Critchley identified a type of parkinsonism caused by cerebrovascular disease in his report on “arteriosclerotic parkinsonism.” It required the development of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 50 years later to find evidence for Critchley’s ideas and what is now commonly known as vascular parkinsonism (VP). Ischemic vascular lesions that may lead to VP are lacunar infarctions, white matter hyperintensities, and less common large vessel infarctions. A comparison of 5 different European studies showed a prevalence rate of 3% of VP. In case the onset of parkinsonism was associated with a cerebrovascular event, VP was diagnosed. Probably the real prevalence is higher because only few patients with VP have an acute onset.

Clinical features

In the classical type of VP, as reported by Thompson and Marsden and FitzGerald and Jankovic, difficulty in walking is the most important initial symptom. Therefore, the classical type is also called lower-half or lower-body parkinsonism. In patients suffering from the classical type, the gait is disordered by shuffling, short steps, variable base (narrow to wide), start and turn hesitation, and moderate disequilibrium. In addition, the arm swing in patients with VP is usually more preserved than in patients with Parkinson disease (PD).

Depending on their onset, 2 types of VP can be distinguished : one with an insidious onset and its vascular lesions diffusely located in the watershed areas (VPi) and the other with an acute onset and lesions located in the subcortical gray nuclei (striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus) (VPa). Winikates and Jankovic later confirmed the 2 different types of onset. In about one-quarter of the patients with VP, the symptoms start acutely.

Clinical features

In the classical type of VP, as reported by Thompson and Marsden and FitzGerald and Jankovic, difficulty in walking is the most important initial symptom. Therefore, the classical type is also called lower-half or lower-body parkinsonism. In patients suffering from the classical type, the gait is disordered by shuffling, short steps, variable base (narrow to wide), start and turn hesitation, and moderate disequilibrium. In addition, the arm swing in patients with VP is usually more preserved than in patients with Parkinson disease (PD).

Depending on their onset, 2 types of VP can be distinguished : one with an insidious onset and its vascular lesions diffusely located in the watershed areas (VPi) and the other with an acute onset and lesions located in the subcortical gray nuclei (striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus) (VPa). Winikates and Jankovic later confirmed the 2 different types of onset. In about one-quarter of the patients with VP, the symptoms start acutely.

Clinical diagnosis

Winikates and Jankovic categorized patients with parkinsonism and a vascular score of 2 or more on a rating scale as having VP. In this way, many patients with PD and vascular risk factors can be misdiagnosed as having VP. Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of VP have been proposed, which are derived from a postmortem examination study. See Box 1 for the criteria for clinical diagnosis of VP.

- a.

Parkinsonism

bradykinesia (slowness of initiation of voluntary movement with progressive reduction in speed and amplitude of repetitive actions in either upper limb or lower limb, including the presence of reduced step length) and at least 1 of the following:

rest tremor, muscular rigidity, or postural instability not caused by primary visual, vestibular, cerebellar or proprioceptive dysfunction

- b.

Cerebrovascular disease

- •

evidence of relevant cerebrovascular disease by brain imaging (CT or MRI) or

- •

the presence of focal signs or symptoms that are consistent with stroke.

- •

- c.

A relationship between these 2 disorders. In practice

- •

an acute or delayed progressive onset with infarcts in or near areas that can increase the basal ganglia motor output (GPe [globus pallidus pars externa] or SNc [substantia nigra pars compacta]) or decrease the thalamocortical drive directly (VL[ventral lateral] nuclei of the thalamus, large frontal lobe infarct). At onset, parkinsonism consists of a contralateral bradykinetic rigid syndrome or shuffling gait within 1 year after a stroke (VPa).

- •

an insidious onset of parkinsonism with extensive subcortical white matter lesions, bilateral symptoms at onset, and the presence of early shuffling gait or early cognitive dysfunction (VPi); the “classical clinical type.”

- •

Exclusion criteria

- •

a history of repeated head injury

- •

encephalitis

- •

neuroleptic treatment at onset of symptoms

- •

the presence of cerebral tumor or communicating hydrocephalus

- •

other alternative explanation for Parkinson syndrome

Etiology

In the “classical clinical type” of VP, parkinsonism is attributed to diffuse periventricular and frontal white matter damage because similar clinical features occur in normal pressure hydrocephalus and in some cases of frontal parasagittal meningioma, in which the same structures are compromised. According to Thompson and Marsden, disconnection of thalamocortical fibers to the supplementary motor area and cerebellar fibers to the leg area is the underlying mechanism that causes the gait disorder in VP.

In accordance with current concepts of putamenal efferents directed toward the basal ganglia output nuclei, one might expect that vascular lesions in the SNc (substantia nigra pars compacta), GPe (globus pallidus pars externa), or the VA (ventral anterior)/VL (ventral lateral) nuclei of the thalamus induce decreased thalamocortical drive to premotor areas and also subsequent development of parkinsonism. According to many previous publications, parkinsonism is also attributed to strategic infarcts in the basal ganglia or thalamus. A causal relationship between strategic infarcts and parkinsonism is reported only in a few publications that described the cases in which the onset is (sub) acute or accompanied by other symptoms of a stroke related to the same lesion. Lesions in specific areas that theoretically can cause parkinsonism (GPe, VL/VA of thalamus, and SNc) have been described by a few investigators. The infarct is located in the hemisphere or brainstem contralateral to parkinsonism in most cases in which a vascular cause is acceptable and a single lesion is seen in the basal ganglia or thalamus.

Pathophysiology

The most supported hypothesis about the pathogenesis of subcortical lesions was originally proposed by Binswanger and Alzheimer. They suggested that the white matter softening can be attributed to subcortical ischemia as a result of arteriolosclerosis of the long penetrating arteries. According to this view, arteriolosclerosis of long penetrating arteries that are poorly provided with collateral anastomoses can result in ischemia of the distal fields of these vessels, that is, periventricularly and in the watershed zones. Transient episodes of hypotension caused by excessive antihypertensive medication or heart failure and hyperviscosity may provoke or aggravate white matter disease in an already compromised cerebral blood flow. The typically hypertensive changes of small vessel disease can occasionally be found in a patient who is not hypertensive or diabetic. Conversely, not every elderly patient with hypertension develops small vessel disease. These points suggest that factors other than hypertension and diabetes, such as a cerebrovascular accident, cardiac disease, or carotid pathology, are probably also involved in the development of hypertensive arteriolopathy. Many investigators stated that the clinical significance of subcortical lesions depends on the severity and location of lesions. A threshold extent of subcortical lesions may be necessary before symptoms appear.

Differential diagnosis

Features that are usually considered to favor a diagnosis of idiopathic PD are also frequently present in VP and include micrographia, cogwheeling, stooped posture, facial masking, hypophonia, and a positive response to levodopa. However, application of the more stringent UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria for the diagnosis of idiopathic PD excludes this diagnosis in most patients with VP. In case a slowly progressive gait disorder presents itself with a shuffling gait, then a normal pressure hydrocephalus or a frontal lobe tumor must be considered. A clinical diagnosis together with a radiologic diagnosis of probable multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), or dementia with Lewy bodies probably excludes a diagnosis of VP in most cases. Dubinsky and Jankovic and Winikates and Jankovic suggested the presence of a particular subtype of VP that they called vascular PSP. In one report, the brains of 2 patients with vascular PSP showed (besides the common diffuse white matter lesions) additional lesions in the dorsal pons and in the thalamus.

Brain Imaging

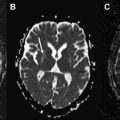

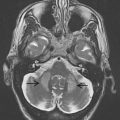

In the last century, CT and MRI were mainly used to exclude hydrocephalus, mass lesions, or subdural hematomas in atypical parkinsonism. They now can support the clinical diagnosis of VP with positive imaging findings. One has to consider the 2 different locations of lesions with their related types of onset: an insidious onset type presenting itself with white matter lesions that are diffusely located in the watershed areas and an acute onset type with lesions located in contralateral strategic areas (globus pallidus, thalamus, substantia nigra, and frontal lobe). MRI is preferred to demonstrate the presence of strategic vascular lesions because of its greater capabilities to show small lesions in regions that are difficult to image with CT, such as the globus pallidus, thalamus, and substantia nigra, and also because of the possibility to scan in different directions (eg, coronal and sagittal). The different T1- and T2-weighted sequences have their own qualities, and when combined, they give complimentary information on the characteristics and probable cause of ischemic pathology. This may be important to fulfill the diagnostic criteria mentioned earlier. T1-weighted images reveal lacunes and frontal cortical infarcts. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) is best suited for the assessment of white matter lesions. It has the advantage of suppressing cerebrospinal fluid signal, allowing a simple distinction of lacunes and perivascular spaces from ischemic white matter lesions, both of which are bright on standard T2-(T)SE weighted images. For the assessment of ischemic lesions in the thalamus and infratentorial regions, conventional T2-weighted images are preferred. In addition, T2 ∗ -weighted gradient echo sequences are more sensitive for the detection of hemorrhagic lacunae than spin echo and FLAIR sequences. An imaging protocol using T1, T2, T2 ∗ , and FLAIR images may therefore optimize diagnostic capabilities of MRI for VP ( Table 1 ). Fig. 1 and 2 show MRI scans in patients with VP with an insidious and an acute onset.

| Coronal 3D T1 gradient echo | TR | 15 ms |

| TE | 7 ms | |

| T1 | 500 ms | |

| Slice thickness | 1 mm | |

| Flip angle | 15°–30° | |

| Axial T2 spin echo | TR | 4000 ms |

| TE | 100 ms | |

| Slice thickness | 3–5 mm | |

| Axial or coronal FLAIR | TR | 8000 ms |

| TE | 102 ms | |

| T1 | 2000 ms | |

| Slice thickness | 3–5 mm | |

| Axial T2 ∗ gradient echo | TR | 650 ms |

| TE | 15 ms | |

| Slice thickness | 3–5 mm | |

| Flip angle | ≥20° |