Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts (TIPS)

Concept and Definition

Concept and Definition

The management of hemorrhagic portal hypertension has undergone interesting changes in the past two decades.1 Current therapeutic options to treat patients with hemorrhagic portal hypertension include medical management, endoscopic sclerotherapy and banding, surgical shunts, liver transplantation, and the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). The TIPS is a nonselective portosystemic shunt that is created by using percutaneous endovascular techniques. Ideally, the procedure should be performed in state-of-the art angiography suites where digital subtraction capabilities exist. Most of these procedures can be completed with the patient in conscious sedation, thereby avoiding the risks of general anesthesia. In essence, the procedure consists of creating a transhepatic communication between one of the hepatic veins and a portal vein branch by using a needle system. The transhepatic track is kept open by metallic stents. The TIPS is an effective method to decompress the hypertensive portal system.1 Its widespread application in the last decade has had a major impact in the management of patients with variceal bleeding by virtually eliminating the need for emergency surgery.1,2 This chapter summarizes the most important clinical and technical aspects of this fascinating procedure.

Historical Perspective

Historical Perspective

In 1969 Rosch and associates described the creation of a transhepatic communication between the hepatic veins and the portal system in a swine model. Colapinto et al4 reported the first clinical attempt to create a transhepatic portacaval communication in a human. In their original description, Colapinto et al reported successful creation of a track between the hepatic and portal veins. Metallic stents were unavailable at the time; so, in an effort to maintain the transhepatic track patent, they placed an angioplasty balloon through the track and kept it inflated in this position for 12 hours.4 Immediately after balloon deflation, the transhepatic track was open; however, 36 hours later, the patient died of sepsis and liver failure.4 Subsequent experience with this technique was discouraging mainly because of the inability to maintain patency of the transhepatic track.5 Metallic stents to keep the transhepatic track open were first used by Palmaz et al5 in 1985 in a dog model. Further basic research was performed between 1985 and 1987 in dog models using both balloon expandable and selfexpandable metal stents.6 The information obtained through this research provided the basis for the first clinical application of the TIPS procedure.6

The first TIPS in humans using metallic stents was performed in 1988 in Heidelberg, Germany. The original description included three patients with severe hemorrhagic portal hypertension refractory to sclerotherapy. The procedure was technically successful in all three patients; one of the patients died of multiorgan failure 11 days after TIPS. The two remaining patients survived, and their quality of life and clinical status were greatly improved.6 Much experience has been gained using the TIPS procedure since its introduction to clinical practice in 1988, and it is now considered an accepted therapeutic option in the management of patients with hemorrhagic portal hypertension.1,2,6,7

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

Clinical Perspective

An accurate clinical assessment of the patient with hemorrhagic portal hypertension is imperative. The interventional radiologist must be familiar with the pathophysiology and differential diagnosis of portal hypertensive states to understand the indications and contraindications for TIPS. The clinical evaluation of these patients must include a problem-oriented history, history of previous surgeries, physical examination, and a detailed assessment of the patient’s clinical condition (e.g., mental status, hemodynamic and respiratory status, laboratory parameters, and quality of life). Ideally, this clinical evaluation should be complemented with a liver ultrasound to rule out the presence of cysts or large masses that could interfere with the creation of the shunt and color Doppler evaluation to assess the patency of the portal vein, splenic vein, hepatic artery, inferior vena cava, and hepatic veins.8 If the information obtained with ultrasound is nondiagnostic, a computed tomography (CT) scan may be performed to delineate more fully certain anatomic details.9 Careful clinical evaluation of the patient, complemented with a liver ultrasound with color Doppler assessment, is strongly recommended for all patients being considered for a TIPS procedure (Fig. 4–1). This detailed assessment of the patient’s condition will help the interventional radiologist to determine whether the patient is a suitable candidate to undergo the procedure.

FIGURE 4–1. (a) Pre-TIPS ultrasound of a 38-year-old man who was sent to our institution for a TIPS to treat refractory ascites. The patient had undergone several paracenteses with persistent fluid reaccumulation in this outside hospital. Sonogram of the right lower quadrant shows a predominantly hypoechoic image with irregular septae and mixed echogenicity. (b) A computed tomographic scan was ordered by the interventional radiologist evaluating the case, which showed a large, ovoid mass, with thick fluid (23 HU) exerting posterior compression of the loops of bowel. TIPS was not performed in this patient, and surgical exploration was recommended. A large, infected mesenteric cyst was found.

Etiology of Portal Hypertension

The underlying cause of the patient’s portal hypertension must be identified before performing a TIPS. Portal hypertension is classified according to the anatomic site of abnormality in three broad categories: prehepatic, intrahepatic, and posthepatic. In prehepatic portal hypertensive conditions, the underlying problem is in the splenoportal or mesoportal system or in the main portal vein. Portal vein thrombosis, splenic vein thrombosis, and splenic arteriovenous fistula are classic examples of prehepatic portal hypertension. Intrahepatic portal hypertension is a broad category that can be divided roughly into presinusoidal, sinusoidal, and postsinusoidal subtypes. Alcoholic cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic active hepatitis are clinical conditions in which the underlying problem is at the sinusoidal level with mixed presinusoidal and sinusoidal components.10 Conditions such as hepatic vein thrombosis and venoocclusive disease are classified as postsinusoidal types of intrahepatic portal hypertension. Finally, portal hypertension secondary to inferior vena cava webs, constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid insufficiency, and right heart failure is classified as posthepatic.10 Decompression of the portal system through the creation of a portosystemic shunt will be beneficial in most patients with intrahepatic portal hypertension. On the other hand, variceal bleeding related to other causes, such as splenic vein thrombosis or the presence of an arterioportal fistula, represent clinical conditions in which a TIPS will not be helpful. The most important reason to determine the etiology of portal hypertension before a TIPS procedure is to identify patients who will benefit as opposed to those who will not benefit from undergoing the procedure.

Child-Pugh Score

The modified Child-Pugh score (Table 4–1) is a simple system used to classify patients according to the severity of their liver disease and has been applied as a predictor of surgical outcome.1,11 Patients who have a score of 5 or 6 are considered good operative risks (class A), those with a score of 7 to 9 are moderate operative risks (class B), and those with a score of 10 or higher are poor operative risks (class C).11,12 Application of the modified Child-Pugh score provides a good description of the severity of the patient’s liver disease and can be used as a predictor of outcome after a TIPS procedure.12–14

APACHE II Score

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score is a scoring system used to predict the risk of death in acutely ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit.12 The APACHE II score has three components: an acute physiology score, age points, and chronic health points.12 The acute physiology score is calculated using the worst value of each of 12 physiological variables: rectal temperature, mean arterial pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, partial pressure of oxygen, arterial pH, serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, hematocrit, white blood count, and Glasgow coma score. Age points are assigned according to the patient’s chronological age, and the chronic health points are assigned according to the patient’s underlying disease (Table 4–2).15 Most patients undergoing a TIPS procedure are assigned five chronic health points on the basis of documented portal hypertension and hepatic failure.12

The application of the APACHE II score for patients undergoing a TIPS procedure was described by Rubin and co-workers in 1995.12 Using logistic regression models, the authors found a high APACHE II score to be the single determinant most closely associated with decreased survival in the month following the TIPS procedure.12 These authors reported that patients with a preprocedural APACHE II score exceeding 18 had a poor prognosis.12 The 30-day mortality rate after a TIPS procedure in Child-Pugh class C cirrhotic patients with an APACHE II score greater than 18 reached 92% in this series.12

The APACHE II score can be calculated easily in acutely ill patients. Interventional radiologists performing TIPS should be familiar with this scoring system because its application provides a realistic appraisal of the patient’s acute clinical situation and it may be used as a predictor of outcome. This information is useful for discussing the therapeutic options and potential outcomes with referring physicians and the patient’s family members. In addition, application of the APACHE II scoring system is encouraged to promote the standardization of reported data.14

Indications

Indications

Soon after its first description, the TIPS procedure enjoyed widespread application mainly because of its apparent low morbidity and mortality.16 A large number of scientific papers and presentations were published between 1991 and 1994 describing the initial results, including technical success and failure rates, bleeding control, procedural complications, and morbidity and mortality rates.16,17 As a response, the National Digestive Diseases Advisory Board convened a scientific conference, which was held in 1994, to review critically the available data on TIPS. As a result of these meetings, formal recommendations on indications for the procedure and issues on the safety and efficacy of the procedure were published.2,16,17

Accepted Indications

Acute Variceal Bleeding Refractory to Endoscopic and Medical Therapy

Variceal bleeding is the leading cause of death in patients with portal hypertension. About 50% of patients with liver cirrhosis who develop esophageal varices eventually develop variceal bleeding.10 The mortality rate for an initial episode of variceal bleeding ranges between 40 to 70%. Spontaneous cessation of variceal bleeding occurs in about 60 to 70% of cases; however, the rebleeding rate is extremely high, about 60% within the first week after the initial episode.10 The TIPS procedure has been proposed as the treatment of choice in patients with acute variceal bleeding for whom treatment with drugs or endoscopic techniques has been unsuccessful.2,16,17 It also may be useful in patients who bleed from portal hypertensive gastropathy or from inaccessible sites such as gastric and intestinal varices.16

Recurrent Variceal Bleeding Refractory to Endoscopic or Medical Therapy

The TIPS procedure is useful in the treatment of patients who develop rebleeding despite adequate medical or endoscopic therapy.16 The alternative therapeutic option in this situation is the creation of a surgical shunt. The decision of the best therapeutic option for each patient needs to be individualized, taking into consideration the patient’s condition and prognosis. In general, it is currently accepted that a patient with good hepatic reserve (Child-Pugh class A) should be treated with a surgical shunt.1,16 The use of TIPS is particularly appealing for patients awaiting a liver transplantation.16,17

Unproven but Promising Uses for TIPS

The TIPS also has been used in the treatment of various complications of portal hypertensive states other than variceal bleeding. Preliminary clinical results have been encouraging, and these indications have been cautiously accepted as “unproven but promising uses for TIPS.”16

Refractory Ascites

Refractory ascites is an uncommon condition in which tense fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity cannot be mobilized by dietary sodium restriction and intensive diuretic therapy. In some patients with tense ascites, superimposed complications such as encephalopathy, renal failure, or electrolyte imbalance may preclude an effective diuretic dosage. This condition causes deterioration of patient’s quality of life and increases the morbidity and mortality rates.18 Treatment options for these patients include repeated large-volume paracentesis, peritoneovenous shunts, portosystemic shunts, and liver transplantation.2,18 The TIPS appears useful in treating patients with refractory ascites, and the initial and midterm results have been encouraging.2,16 The most difficult challenge in this population is to identify those patients who truly suffer from the condition. The use of TIPS is not advocated as the initial therapy for every patient with massive ascites; rather, it is recommended for patients who do not respond to the conventional approaches, including large-volume paracentesis.16

Cirrhotic Hydrothorax

Cirrhotic hydrothorax is the accumulation of ascitic fluid in the chest cavity.19 The TIPS has also been reported to be helpful in the treatment of this infrequent complication.16,19,20

Budd-Chiari Syndrome

Budd-Chiari syndrome results from obstruction to the hepatic venous outflow tract because of occlusion of the hepatic veins or the inferior vena cava.21 This syndrome has a wide variety of causes and manifestations, and therefore a variety of treatment options, including medical, endovascular, and surgical methods, are available.21,22 Endovascular techniques, including angioplasty, stent placement, thrombolysis, and TIPS, have been useful in the treatment of the various forms of Budd-Chiari syndrome.22 For the most part, TIPS has been recommended in patients with acute and chronic Budd-Chiari syndrome and deteriorated liver function with symptomatic portal hypertension.22 Because the long-term patency of these shunts is poor, this application for TIPS has been proposed mainly for patients awaiting a liver transplant.2,21 The Budd-Chiari syndrome is discussed in depth in Chapter 7.

Venoocclusive Disease

Patients with veno-occlusive disease may present with clinical features identical to those of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. This condition is most commonly seen after bone marrow transplantation21,23 but also has been described in patients with acute and chronic leukemias and after whole abdominopelvic irradiation.24 The TIPS has been used in a limited number of patients with this condition,21,25 and overall patient survival has been poor despite successful portal decompression.23,26

Newly Described Indications

This group includes, for the most part, preliminary clinical results on small series of patients and case reports. The application of a TIPS in these conditions has not been proven useful; because of the lack of better therapeutic alternatives, however, its application appears to be justified.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is a complication that occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis and ascites. This syndrome includes the development of renal failure and marked alterations in systemic hemodynamics and vasoactive systems. The prognosis of patients with this disorder is poor.27 The TIPS has been used in a small number of patients with hepatorenal syndrome.28 In a prospective trial, the procedure was used in seven patients with type I hepatorenal syndrome.28 Shunts were successfully created in all cases.28 This study demonstrated an improvement in the renal function with a decrease in the activity of the renin-angiotensin system. Two patients died early (i.e., within 30 days of the procedure), and only three patients survived longer than 3 months.28 The results of this study suggest that a TIPS has a beneficial impact in the renal function of patients with hepatorenal syndrome type I; however, long-term survival is unlikely to improve.28 More experience needs to be gained before TIPS can be proposed as an accepted treatment for this condition.

Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

The hepatopulmonary syndrome is a condition that includes liver disease, increased alveolar-arterial gradient on room air, and evidence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatation.29 This syndrome is caused by functional right-to-left shunts secondary to intrapulmonary vascular dilation. As a result, gas exchange is impaired, along with clinical manifestations of hypoxemia, cyanosis, and clubbing.29 TIPS has been used in a few patients with intractable hepatopulmonary syndrome with excellent clinical results.29,30 Improvement in oxygenation and a mild decrease in clubbing have been described up to 4 months after a TIPS procedure.29

Other Bleeding Problems

The TIPS also has been used successfully in patients with bleeding problems caused by portal hypertension in sites other than esophageal and gastric varices. These conditions are relatively uncommon but may include bleeding from intestinal varices,31,32 portal hypertensive colopathy,33 stomal varices,34,35 rectal varices,36 portal hypertensive stomapathy,37 and caput medusae.38

Uses Where a TIPS Is Not Indicated

It is generally accepted that a TIPS should not be used to treat patients who have not had an episode of variceal bleeding. Likewise, the procedure is not indicated to facilitate liver transplantation in patients who have not had bleeding. These “prophylactic” applications of a TIPS are not warranted in current medical practice.16,39

Contraindications

Contraindications

Absolute Contraindications

Right-sided Heart Failure with Elevated Central Venous Pressure

An increase in the venous return to the right system can occur after a successful TIPS procedure40,41 and may have fatal consequences by exacerbating an underlying right-sided heart failure.16,42,43

Polycystic Liver Disease

Polycystic liver disease has been considered an absolute contraindication to TIPS, mainly because of the potential of causing a massive bleeding during the procedure.16 This long-standing concept was challenged by a case report describing successful creation of a TIPS in a patient with polycystic liver disease.9 Although the procedure can be more labor intensive than a standard TIPS, careful preprocedural planning may allow the creation of a TIPS in patients with such a condition.9 Certain concerns remain valid before the creation of a TIPS in a patient with polycystic liver disease: The effect of contact between the metallic stent and the cystic fluid on shunt patency is unknown9; in addition, the creation of a communication between the transhepatic track and an infected cyst cavity may cause a septic complication and worsen the patient’s clinical condition. Further experience with similar cases must be obtained before TIPS can be recommended in patients with this condition.

Severe Hepatic Failure

A successful TIPS may cause total portal flow diversion; that is, the liver loses its portal venous inflow. In this circumstance, blood flow to the liver must be supplied entirely by the hepatic artery. If the hepatic arterial response is insufficient after total portal flow diversion, the liver may undergo severe ichemia with consequent liver failure. The risk appears to be greater in patients who present with signs of liver failure before TIPS. For this reason, placement of a TIPS in a patient with severe hepatic failure should be avoided.40,43

Relative Contraindications

Active Intrahepatic or Systemic Infection

Patients with a known active intrahepatic or systemic infection must be treated before creation of a TIPS. In emergent situations, the procedure still can be performed; antibiotic coverage is started before the procedure and continued thereafter until a full course is completed. Patients with previous biliary surgery with bilioenteric anastomoses may have chronic colonization of the biliary system. These patients should be treated with systemic antibiotics because, if untreated, this condition may lead to sepsis after a successful TIPS.

Severe Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy may develop in up to 45% of patients after a TIPS procedure.44 The condition of a patient with severe encephalopathy before TIPS may worsen after the procedure. On the other hand, some patients develop encephalopathy in relation to a bleeding episode and may show improvement of mental status after a successful TIPS. The potential risks and benefits must be evaluated before creating a TIPS in the patient with severe encephalopathy.

Portal Vein Thrombosis

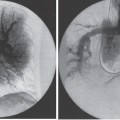

A successful TIPS can be performed in the face of portal vein thrombosis (Fig. 4–2).45 The results may be better in patients with acute portal vein thrombosis compared with patients with long-standing portal vein thrombosis and cavernous transformation.45,46 All these aspects must be evaluated carefully before embarking on a difficult, technically challenging TIPS procedure.

Patient Preparation

Patient Preparation

The indication for a TIPS must be discussed with referring physicians. Ideally, a transplant surgeon should be involved to determine whether the patient is a potential candidate for liver transplantation. The risks and benefits expected from the procedure must be outlined clearly to the patient and the patient’s family, and written consent must be obtained. The preprocedural patient preparation is extremely important. Certain aspects of patient care immediately before a TIPS need to be addressed in preparation for the procedure.

FIGURE 4–2. (a) Portal vein thrombosis. Direct portogram shows multiple large filling defects within the main portal vein and intrahepatic branches, consistent with acute portal vein thrombosis. Large varices are demonstrated (arrow), (b) Direct splenoportogram after TIPS creation demonstrates a patent shunt. The esophageal varices are no longer opacified.

Transfusions

No specific written guidelines exist regarding the transfusion of blood products on patients undergoing a TIPS; however, most decisions are straightforward and should be supported by good clinical judgment. In patients with active variceal bleeding, red blood cells and plasma products should be administered to maintain stable vital signs.47 Frequently, transfusion of fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) or cryoprecipitate is required to correct the prothrombin time (PT). Two units of FFP are usually sufficient to correct an elevated PT.48 The corrective effect of a unit of FFP lasts about 6 hours because of the half-life of the coagulation factor VII.48 Transfusion of plasma products should be coordinated so that the maximal effect is obtained during the critical steps of the procedure.48 In some cases, it is impossible to correct the coagulation profile completely, and the decision of whether to proceed with the TIPS must be discussed with all the physicians involved in the case.

One unit of platelets usually will raise the platelet count by 5–10 × 109/L. Platelets are obtained from platelet-pheresis donations. One unit provides a greater total number of platelets in the same volume, approximately equal to 6 U of whole-blood-derived platelets.48 In some cases, the half-life of platelets after transfusion can be limited; once again, transfusion of these cells must be coordinated so that maximal counts are achieved at the expected critical steps of the procedure. In general, it is agreed that a patient with platelet counts lower than 30–40 × 109/L will require transfusion of these cells.48,49

Prophylactic Antibiotics

Death related to sepsis is one of the most common complications reported after a TIPS procedure.50–54 Liver cirrhosis is known to be associated with a derangement of the immune system. For this reason, cirrhotic patients have an increased risk of developing spontaneous and procedure-related infectious problems.52 Certain standard precautions may help to reduce the infectious rate: (1) careful attention to sterile technique, (2) glove change if the procedure extends longer than 2 hours, and (3) double gloving to prevent contamination from small perforations in the gloves.52 Despite application of these basic precautions, certain factors increase the risk of infection on patients undergoing a TIPS, including (1) multiple transhepatic punctures, (2) long procedural time, (3) multiple stenting, and (4) periprocedural placement of central lines.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics on patients undergoing a TIPS procedure is a controversial issue. In current practice, three different approaches have been reported: (1) intravenous antibiotics are used before the procedure as a standard practice,50,54,55 (2) antibiotics are used on a per case basis,56 or (3) no prophylactic antibiotics are used.51,53 Deibert and colleagues52 conducted a prospective randomized study to evaluate the effect of a single dose of cefotiam, a second-generation cephalosporin, as a prophylactic antibiotic in patients undergoing a TIPS procedure.52

In this series, 105 interventions in 87 patients were performed. Eighty-three interventions were de novo TIPS implantations, and 19 were TIPS revisions. Patients treated with antibiotics during the 2 weeks before randomization or patients with clinical or laboratory signs of infection were excluded.52 The primary endpoint of the study was infection within 5 days after the intervention. Postinterventional infection was defined as elevated white cell count of greater or equal to 15,000/μl, temperature of 38.5°C or higher, or positive blood cultures after the intervention.52 The authors concluded that a single dose of cefotiam was not useful as a pre-TIPS prophylactic regimen.52 Despite these conclusions, the study reported some interesting findings: (1) overall, a single antibiotic dose decreased the rate of infection from 20% to 14% in all TIPS interventions (not statistically significant); (2) patients undergoing a de novo TIPS procedure had an infection rate of 25% without antibiotics and 17% after a single antibiotic dose (p< 0.32); (3) none of the patients who underwent a TIPS revision procedure had an infectious complication, regardless of antibiotic treatment; and (4) patients with an elevated body temperature before the intervention (37–38°C), transjugular embolization of varices, multiple stenting, and central venous line had a significantly higher infection rate than patients without these characteristics.52 Although the results obtained by Deibert et al52 did not reach statistical significance, they suggested a trend toward a decreased risk of infection with the use of prophylactic antibiotics. We believe the use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients undergoing TIPS is not unreasonable. In current practice, about 70% of interventional radiologists performing TIPS use prophylactic antibiotics on a routine basis.51,55 The recommended antibiotics are second-generation cephalosporins.51 On the other hand, we do not believe that prophylactic antibiotics are necessary for TIPS revision procedures.52

Anesthesia Considerations

Patients undergoing a TIPS procedure require constant monitoring of vital signs. Most interventional radiologists currently perform TIPS with the support of an anesthesia team. Most procedures can be performed with the patient under conscious sedation; however, in some centers, general anesthesia is preferred.57,58 An interesting approach is the use of a laryngeal mask to obtain adequate patient sedation without the risks of the traditional general anesthesia.59

Technique

Technique

Vascular Access

Vascular access using the right internal jugular vein is the preferred approach to perform a TIPS. Sonographic guidance for vein puncture is highly recommended. The use of ultrasound allows precise, rapid placement of the needle within the lumen of the jugular vein with a minimal risk for complications.60 In addition, anatomic variants and vessel occlusions can be readily identified, thus avoiding unnecessary punctures. If the right internal jugular vein is occluded or cannot be used for any other reason, the best alternative is the left internal jugular vein.50,61 At our Institution, we have performed more than 40 TIPS procedures using a left internal jugular vein approach with a 100% technical success and no associated procedural complications. A TIPS also can be performed using the right external jugular vein50; however, it is technically more difficult to manipulate the needle and the catheters through this approach. A femoral vein access for TIPS creation has been used only in a patient with aberrant portal venous anatomy,50,62 and its use as a standard access to attempt a TIPS is currently not recommended.50

Once that vascular access has been secured, a 10F, 40-cm-long, vascular introducer sheath is advanced into the inferior vena cava. The sideport of the sheath is connected to the pressure transducer, and pressure measurement in the inferior vena cava is obtained. Subsequently, the sheath is withdrawn to the right atrium, and pressure is measured at this location. After initial pressure measurements, a curved angiographic catheter is introduced, and catheterization of the hepatic veins is performed. The preferred vein is the right hepatic vein since this vessel has an almost constant anatomic position and lies posterior to the right portal vein in most patients (Fig. 4–3).45,63 One of the most important technical steps during a TIPS procedure is selection of the optimal hepatic vein. Ideally, a TIPS should be performed by creating a track between the right hepatic vein and the right portal vein. If the right hepatic vein is too small or too difficult to catheterize, the middle hepatic vein can be used.45 Creation of a shunt using the left hepatic vein is technically more demanding, but, if necessary, this vein also can be used. Once the best available vein has been catheterized, a wedge hepatic pressure is obtained. With this information, a rough calculation of the portosystemic gradient can be obtained.

FIGURE 4–3. Hepatic venogram showing a patent, normal-caliber hepatic vein. This vessel is suitable for TIPS creation.

Portal Vein Localization

Gaining access to the portal vein is probably the most difficult step during a TIPS procedure. Several methods to localize the portal vein have been described. The original description of the TIPS procedure included placement of a transhepatic catheter into the portal vein.6,64 This practice was abandoned because excessive bleeding through the transhepatic tract increased the procedure mortality.64 Other localizing methods that have been used include the direct catheterization of the portal vein through a patent paraumbilical vein,50 percutaneous puncture of the portal vein with a skinny needle followed by placement of a small 0.018-inch guidewire,45 placement of a radiopaque marker into the hepatic artery by a femoral approach,65 indirect localization using either splenic or superior mesenteric arteriogram,66 real-time sonographic guidance,2 and wedged hepatic venogram using either contrast or CO2.45 The wedged hepatic venogram may be obtained by advancing the angiographic catheter to the most peripheral portion of the hepatic vein or by using an occlusion balloon.45 For practical purposes, the fastest, most effective method for portal vein localization is the wedged hepatic venogram using CO2.45,57,67 With this method, the portal vein can be opacified in more than 90% of the cases, and the image is superior compared with the wedged hepatic venogram using iodinated contrast (Fig. 4–4).45,67 Once the portal vein has been clearly identified, the next step is to advance the needle system in preparation for the transhepatic puncture.

FIGURE 4–4. (a) Wedged hepatic venogram with iodinated contrast media. The angiographic catheter has been advanced to the most peripheral portion of the hepatic vein (white arrowhead). The intrahepatic right portal vein is demonstrated (arrowhead). In addition, a portion of the liver parenchyma is also opacified (curved arrow). (b) Wedged hepatic venogram using CO2 demonstrates excellent opacification of the portal venous system, including right and left intrahepatic branches and main portal vein.

Portal Vein Access

Needle Systems

Different types of needle systems are available to perform the transhepatic puncture. Probably the most widely used access system is the RUPS-100 Rosch-Uchida transjugular access set45,66 (Cook, Bloomington, IN) (Fig. 4–5). An alternative system is the RTPS-100 Ring transjugular liver access set (Cook, Bloomington, IN) (Fig. 4–6). Fine-needle systems are also available, such as the Cope-Ring portal vein access set (Cook, Bloomington, IN) and the Angiodynamics set (AngioDynamics, Glens Falls, NY) (Fig. 4–7). Although in theory the fine-needle systems are less traumatic, a decreased morbidity rate has not been demonstrated with their use when compared with larger-gauge systems.45 Thus, the use of either needle system depends entirely on operator preference.

FIGURE 4–5. (a) Photograph shows Rösch portocaval shunt set, RUPS-100 (Cook, Bloomington, IN). A, 10F introducing sheath and 10F vessel dilator; B, 10F Teflon catheter; C, 14-gauge transjugular needle; D, 5F Teflon catheter; E, 62.5-cm flexible-tip needle, (b)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree