CHAPTER 76 Venous Anatomy of the Abdomen and Pelvis

ABDOMEN: PORTAL VENOUS CIRCULATION

General Anatomic Description

Detailed Description of Specific Areas

Portal Vein

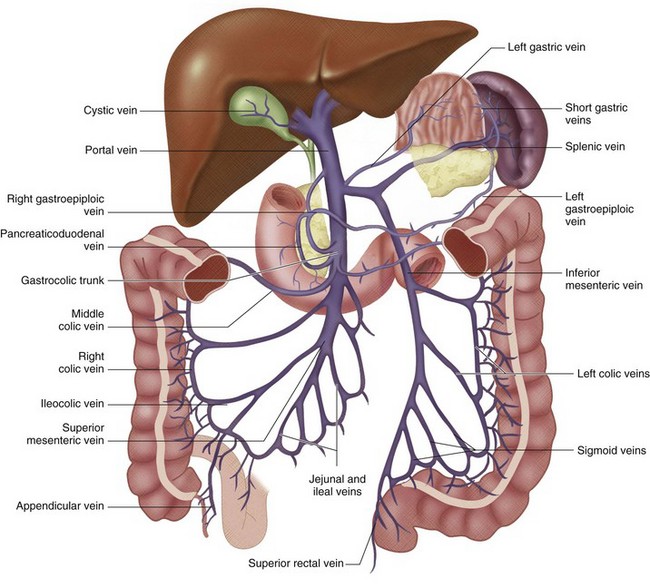

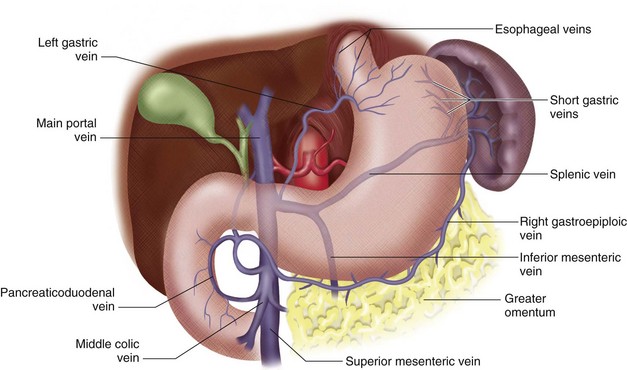

The portal vein (PV) is approximately 7 to 8 cm long in adults and is formed by the union of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein at the level of the second lumbar vertebra.1 It lies posterior to the pancreatic head and anterior to the IVC (Figs. 76-1 to 76-3). The PV enters the liver at the porta hepatis, where it runs posterior and medial to the bile duct and posterior and lateral to the hepatic artery. At the porta hepatis, the PV divides into the right and left PVs. Of note, the adult PV and its tributaries are devoid of valves. However, in the fetus and for a brief postpartum period, valves can be found in portal tributaries.

Superior Mesenteric Vein

The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) drains the small intestine, cecum, appendix, and the ascending and transverse portions of the colon (see Fig. 76-1). It courses posterior to the head of the pancreas and horizontal segment of the duodenum, and lies anterior to the IVC. The SMV unites with the splenic vein to form the main PV.

Splenic Vein

The splenic vein (lienal vein) is the second largest tributary of the PV and measures about 1 cm in diameter. The main splenic vein is formed by the union of two (76%), three (20%), or four (4%) inflow veins.2

Normal Variants

In a study by Koc and colleagues, a total of 318 branching variants and anomalies of the portal venous system were observed in 307 (27.4%) of 1120 patients3; 72.6% of patients demonstrated conventional anatomy. The most frequent variation was trifurcation of the PV, detected in 12.4% of patients. In these individuals, the PV divided into a left portal branch, right anterior portal branch, and right posterior portal branch. The next most common variant was a right posterior portal branch as the first branch of the main portal vein, detected in 9.2% of cases. In 3.6% of patients, there were variants of PV origin in segments IV and VIII of the liver.

Another variant of the PV seen in very rare cases is infracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR), in which the pulmonary veins drain into the PV. The incidence of TAPVR is approximately 2% of all congenital heart defects and, in 15% of cases, the pulmonary veins drain into the portal venous system (type III).3,4

In most cases, the SMV is formed by its chief tributaries. However, in almost 13% of cases, the main trunk of the SMV is absent and large right and large left mesenteric branches join the splenic vein to form the portal vein.3,4

The inferior mesenteric vein demonstrates considerable anatomic variability. In a study by Graf, the inferior mesenteric vein drained into the splenic vein in 56% of patients, but in 18% it drained into the splenoportal angle, and in the remaining 26% drainage was observed into the superior mesenteric vein.5

Differential Considerations

Portal Hypertension

A number of different factors can result in increased pressure in the portal system. These can be divided into prehepatic, intrahepatic and posthepatic causes (Table 76-1).

TABLE 76-1 Causes of Portal Hypertension

| Prehepatic | Intrahepatic | Posthepatic |

|---|---|---|

| Portal vein thrombosis |

Patients with portal hypertension may be asymptomatic, but most manifest with variceal bleeding, ascites, splenomegaly, or encephalopathy. In variceal bleeding, 85% of cases result from variceal hemorrhage at the gastroesophageal junction. Bleeding from gastric and esophageal varices account for 17% of cases of acute massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.6

Treatment options for portal hypertension include medical management, surgical devascularization with portosystemic shunt formation, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and liver transplantation.7

ABDOMEN: SYSTEMIC VENOUS CIRCULATION

Detailed Description of Specific Areas

The IVC is formed by the union of the common iliac veins at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra (Fig. 76-5).1 It ascends to the right of the abdominal midline, anterior to the vertebral column, in the retroperitoneal space and traverses the tendinous portion of the diaphragm at the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra, draining into the right atrium. A semilunar valve is present at its atrial orifice (valve of the inferior vena cava), which in fetal life serves to direct blood through the foramen ovale into the left atrium, which becomes rudimentary in the adult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

FIGURE 76-1

FIGURE 76-1

FIGURE 76-2

FIGURE 76-2

FIGURE 76-3

FIGURE 76-3

FIGURE 76-4

FIGURE 76-4

FIGURE 76-5

FIGURE 76-5