1 Conventional Morphological Imaging: MRI Remains the Workhorse

1.1 Introduction

The term brain tumor refers to a collection of neoplasms, each with its own biology, imaging appearance, treatment, and prognosis. 1 This chapter provides an overview of the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of common intracranial neoplasms, primarily focusing on intra-axial neoplasms.

For the purpose of discussion and based on the cell of origin, the intracranial tumors discussed herein have been classified as follows:

Tumors of the Neuroepithelial Tissue

Astrocytic Tumors

Oligodendroglial/oligoastrocytic tumors

Neuronal and mixed neuronal–glial tumors

Embryonal tumors

Lymphoma

Metastasis

1.2 Tumors of the neuroepithelial tissue

1.2.1 Astrocytic tumors

These can be categorized into eight types based on their histopathological appearance:

Pilocytic astrocytoma

Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA)

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA)

Diffuse astrocytoma

Anaplastic astrocytoma

Glioblastoma

Gliosarcoma

Gliomatosis cerebri

Pilocytic Astrocytoma

Pilocytic astrocytoma is the most common pediatric central nervous system (CNS) glial neoplasm. 2 The tumor has a benign biological behavior, categorized as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, with an extremely high survival rate of 94% at 10 years, the best of any glial tumor. The cerebellum, optic nerve and chiasm, and hypothalamic region are the most common locations, but the tumor can be found anywhere in the brain and spinal cord. Leptomeningeal metastases are rare. Most patients present in the first 2 decades, and clinical symptoms and signs are usually of several months’ duration and are directly related to the specific location of the tumor.

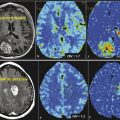

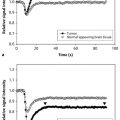

MRI typically demonstrates a slow-growing, relatively well circumscribed tumor, with a predominant cystic component (Fig. 1.1). A variable degree of enhancement is seen following contrast administration. The most common pattern of enhancement is that of an avidly enhancing mural nodule with a nonenhancing cyst (50% of cases). The wall of the cyst occasionally enhances. Other tumor patterns include a heterogeneously enhancing lesion and a solid homogeneous enhancement. 3 Surrounding vasogenic edema is rarely present. Foci of susceptibility likely related to calcifications can be seen in 20% of cases. Hemorrhage is very rare. These masses often cause obstructive hydrocephalus.

Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma

SEGA is an intraventricular glioneuronal tumor arising from the ventricular wall near the foramen of Monro. It is the most common cerebral neoplasm in tuberous sclerosis. The tumor is characterized by slow growth and a benign biological behavior (WHO grade I).

MRI demonstrates a well-circumscribed, lobulated, heterogeneous mass, with avid enhancement (Fig. 1.2). Associated foci of susceptibility related to calcification can sometimes be seen. There is typically no leptomeningeal spread. 4

Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma

PXA is a rare, usually benign brain tumor. It is seen almost exclusively as a neoplasm of children and young adults. It is characterized as a WHO grade II tumor. It is supratentorial in approximately 98% of cases. Most often, it involves the superficial cortex of the temporal lobes. The overlying leptomeninges are commonly involved.

MRI demonstrates a round to oval, predominantly cystic, cortical mass with an enhancing mural nodule (Fig. 1.3). The enhancing nodule tends to abut the pial surface. 5 Adjacent leptomeningeal enhancement and an enhancing dural “tail” are commonly seen. Minimal surrounding edema is rarely present. Calcifications, hemorrhage, and skull erosion are rarely seen.

Diffuse Astrocytoma

Diffuse astrocytoma is a well differentiated but diffusely infiltrating primary brain neoplasm of astrocytic origin (WHO grade II). It represents approximately 10 to 15% of all astrocytomas, and it typically affects young adults in the third to fourth decade of life. It has an intrinsic tendency for malignant progression to anaplastic astrocytoma, and glioblastoma. 6

Diffuse astrocytoma is a white matter neoplasm that may extend into the cortex. Frontal and temporal lobes are the sites most commonly involved. About 20% involve the deep gray matter structures, thalamus, and basal ganglia. Involvement of the spinal cord is less common. In children and adolescents, the brainstem (mostly pons and medulla) is the most common site of involvement.

MRI demonstrates an ill-defined mass iso- to hypointense to the gray matter on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), and hyperintense on T2WI (Fig. 1.4). Minimal surrounding edema is occasionally seen. Cysts, calcification, and hemorrhage are rarely seen. Restricted diffusion is typically absent. There is usually no associated enhancement seen. In fact, the presence of enhancement can suggest progression to a higher-grade neoplasm. 7

Anaplastic Astrocytoma

Anaplastic astrocytoma is a diffusely infiltrating astrocytoma with focal or diffuse anaplasia and marked proliferative potential. It is a WHO grade III neoplasm and represents approximately 25% of all astrocytomas. Anaplastic astrocytoma predominantly involves the hemispheric white matter and is commonly found in the frontal and temporal lobes. Less commonly, it involves the brainstem and spinal cord. In children, it may involve the pons and the thalamus.

MRI demonstrates an ill-defined mass iso- to hypointense to the gray matter on T1WI, and hyperintense on T2WI. Minimal surrounding edema can sometimes be seen. Enhancement, when seen, is often focal, patchy, and heterogeneous. Cysts, calcification, and hemorrhage are rarely seen. Restricted diffusion is typically absent. Presence of prominent flow voids and ringlike enhancement are features suggestive of progression to glioblastoma. 7

Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma is the most common primary brain malignancy, accounting for 12 to 15% of all intracranial neoplasms. It is a WHO grade IV tumor and accounts for 60 to 75% of all astrocytic tumors. It occurs most frequently in the cerebral hemispheres of adults between 45 and 70 years of age. Most glioblastomas arise de novo. The mean age of such patients who present with primary glioblastoma is 55 years. Glioblastomas may also arise from an existing astrocytoma that has undergone progression to a higher grade. Such secondary glioblastomas are found in a younger patient population (mean age, 40 years) and are characterized by a longer clinical course. 8 , 9

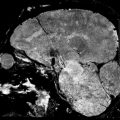

Glioblastoma is a rapidly enlarging malignant astrocytic tumor characterized by necrosis and neovascularity. Glioblastomas are more frequently found in the supratentorial white matter, most commonly in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes. The occipital lobes are relatively spared. Glioblastomas typically appear as poorly marginated, diffusely infiltrating, necrotic, hemispheric masses. These tumors cross the white matter tracts to involve the contralateral hemisphere. They frequently extend across the corpus callosum (“butterfly glioma”) and can also involve the anterior and posterior commissures (Fig. 1.5). These tumors may be multifocal or multicentric.

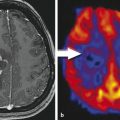

Most often, imaging shows heterogeneously enhancing, partially necrotic mass lesion with surrounding edema and mass effect. 9 Based on the underlying genetic profile, this appearance can vary. Diffusion restriction from some of the solid components suggestive of hypercellularity is commonly seen. Foci of susceptibility suggestive of hemorrhage are commonly seen. Calcifications are rare because these tend to be related to low-grade tumor degeneration. Surrounding fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal abnormality suggests edema and tumor infiltration, which in fact extends far beyond the signal abnormality changes. 9

Gliosarcoma

Gliosarcoma is a rare primary brain tumor that is composed of neoplastic glial cells mixed with a spindle cell sarcomatous element (WHO grade IV). The sarcomatous element is thought to arise from neoplastic transformation of vascular elements within the glioblastoma. Gliosarcomas present in the sixth to seventh decade of life. The temporal lobes are commonly involved. Imaging findings and clinical presentation can be indistinguishable from glioblastoma. The presence of dural involvement can suggest the presence of gliosarcoma. 10

Gliomatosis Cerebri

According to the current WHO classification system for brain tumors, gliomatosis cerebri is a distinct malignant neuroepithelial neoplasm of uncertain origin. 11 The overall biological behavior corresponds to WHO grade III in a majority of cases. Gliomatosis cerebri typically involves the hemispheric white matter. Associated involvement of the cortex is often seen. There is diffuse white matter infiltration of three or more lobes and also involvement of the basal ganglia, thalami (in 75% of cases), corpus callosum (in 50% of cases), and brainstem and spinal cord (in 10–15% of cases). In 10% of cases there is also cerebellar involvement. This tumor infiltrates and enlarges the involved structures. However, it preserves the underlying brain architecture. 12 Patients usually present between the third and fifth decades of life, but cases have been described in patients of all ages, from neonates to the elderly. There is no gender predilection.

Imaging shows a poorly defined, nonenhancing, infiltrative lesion involving three or more lobes, with blurring of the gray–white differentiation and expansion of the involved parenchyma (Fig. 1.6). Associated mass effect is common but is less when compared with the size of the tumor. Enhancement may indicate malignant progression or a focus of malignant glioma. There is usually no abnormal diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). 13

1.2.2 Oligodendroglial/Oligoastrocytic Tumors

Oligodendroglioma

Oligodendroglioma is the third most common glial neoplasm. It accounts for 2 to 5% of primary brain tumors and 5 to 18% of all glial neoplasms. 14 Males are affected more frequently, and the peak manifestation is during the fifth and sixth decades.

Currently two main types of tumors are recognized histopathologically: well-differentiated oligodendroglioma (WHO grade II) and its anaplastic variant (WHO grade III). Less commonly, neoplastic mixtures of both oligodendroglial and astrocytic components occur. These have both well-differentiated and anaplastic forms and are referred to as oligoastrocytomas. 15

Although it is most common in the frontal lobes, additional sites of involvement include temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Posterior fossa involvement is rare. There is an uncommon intraventricular variant of oligodendroglioma seen in approximately 1 to 10% of cases. 14 , 15

Imaging shows a heterogeneous mass lesion within the subcortical white matter with extension to the cortex (Fig. 1.7). Heterogeneity is related to calcifications (70–90%), cystic change (20%), and, uncommonly, blood products. Mild surrounding edema may be seen. The tumor may expand, remodel, or erode the adjacent calvarium. On occasion, frontal lobe tumors may extend through the corpus callosum to produce a “butterfly glioma” pattern. No diffusion restriction is seen. The presence of enhancement is usually associated with a higher-grade tumor. However, such enhancement is uncommonly seen with low-grade oligodendrogliomas as well. In fact, the absence of enhancement does not definitely indicate a low-grade tumor. Histological confirmation is always desired. 15

Tumors with 1p and 19q deletions have interesting imaging features. They are more likely to demonstrate calcification and demonstrate ill-defined margins on T1WI. 16 They are also more likely to be found in the frontal lobe and extend across the midline than tumors that lack these deletions, which are more common in the temporal lobe, insula, and midbrain. 17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree