SK2 Button Sequestration

SK3 Cystic Lesions of the Mandible of the Skull

SK4 Diffuse Demineralization

SK5 Enlargement or Destruction of the Sella Turcica

SK6 Increased Radiodensity of the Calvarium

SK7 Intracranial Calcifications

SK8 Mass in the Paranasal Sinuses

SK9 Multiple Wormian Bones

SK10 Osteolytic Defects of the Skull

SK11 Radiodense Mandible Lesions

SK1. Basilar Invagination

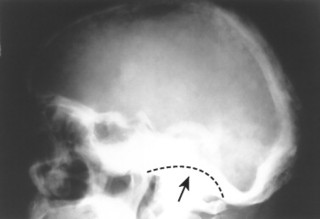

Basilar invagination (or basilar impression) is an upward migration deformity of the base of the skull. Platybasia is an anthropologic term describing flattening of the skull base and should not be used synonymously with basilar invagination. The major causes of basilar invagination are summarized by the mnemonic COOP (congenital, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomalacia, and Paget’s disease).

McGregor’s line is a widely used roentgenometric method to detect the presence of basilar invagination. It involves drawing a line segment from the posterior aspect of the hard palate to the inferior margin of the skull on the lateral radiograph. Basilar invagination is probable if the tip of the odontoid process is more than 8 mm above the line segment in men or 10 mm in women.

The diagnosis of basilar invagination is made with conventional radiography and is supplemented by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is particularly helpful to assess possible concurrent neurologic involvement.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Bone-softening disorders(FIG. 16-1) | Alterations of the skull base secondary to bone-softening diseases: osteogenesis imperfecta, rickets, osteomalacia, and Paget’s disease. |

| Less common | |

| Congenital anomalies | Alterations of the skull base associated with atlantooccipital fusion (occipitalization or assimilation), Klippel-Feil syndrome, and stenosis of the foramen magnum. |

| Achondroplasia [p. 421] | Rhizomelic dysplasia resulting from a congenital defect of enchondral bone formation; characteristics include rounded lumbar “bullet-nosed” vertebrae, lumbar spine kyphosis, posterior vertebral body scalloping, increased intervertebral disc height, flattened vertebral bodies, narrowed spinal canal, and alterations of the skull base; the pelvis may appear hypoplastic; milder expressions of the disease may occur. |

| Arnold-Chiari malformation [p. 1395] | Malformation of the skull base with caudal displacement of the cerebellomedullary region; several levels of inferior displacement are recognized. |

| Cleidocranial dysplasia [p. 425] | Defect of intramembranous bone formation manifesting as osseous defects of the calvarium, clavicles, and pelvis; associated with persistence of metopic suture. |

| Trauma | Posttraumatic deformity from a skull fracture. |

A button sequestration is a small, solitary osteolytic bone lesion that contains a central focus of calcification. Often this change represents a normal variant, particularly if it is surrounded by an osteosclerotic margin (“donut lesion”); however, aggressive pathologies should be considered.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

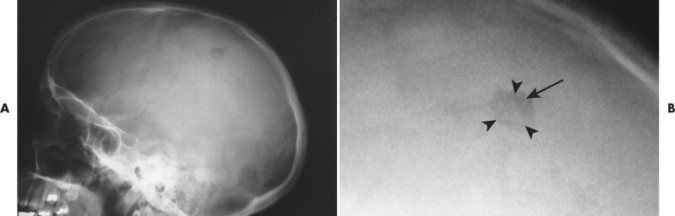

| Eosinophilic granulomas(FIG. 16-2) [p. 935] | Common cause of osteolytic skull defects; the inner and outer skull tables are affected; however, the defects in the skull tables do not completely superimpose, leaving an appearance of a beveled margin. |

| Infection | Osteolytic defects may occur secondary to Staphylococcus, syphilis, or tuberculosis infections; often result from contiguous spread of scalp infection. |

| Bone metastasis [p. 889] | Primary carcinomas from the lung, breast, prostate, and colon commonly metastasize to the skull. |

| Normal variant | Radiolucent defects with central calcification and surrounding sclerosis, possibly representing normal variants; these defects are differentiated from true button sequestrations by the absence of reported pain and disability; these variants usually are discovered incidentally and are not clinically significant. |

| Less common | |

| Necrosis | Osteonecrosis resulting from irradiation, electric shock therapy, or electric burns; often a latent period of several years elapses before osteolytic lesion becomes apparent. |

| Postsurgical | Burr hole or shunt placement. |

| Primary neoplasm | Epidermoid, dermoid cyst, meningioma, and hemangiomas may cause radiolucent skull lesions. |

Cystic lesions of the mandible are often caused by pathologies that produce cystic lesions elsewhere in the skeleton and a variety of causes that are seen only in the mandible. Most pathologies comprising the latter group are related to pathological conditions of the teeth.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Dentigerous (follicular) cyst(FIG. 16-3) | Well-circumscribed mandibular cyst that characteristically contains the crown of an unerupted tooth; this cyst is usually found in children. |

| Periodontal cyst | Common cyst of the jaw that develops from chronic infection; it appears as a well-defined radiolucent cyst in the periapical location and is contained within osteosclerotic margins. |

| Periapical granulomas | Well-circumscribed cyst in a periapical location, which may develop into periodontal cyst. |

| Less common | |

| Ameloblastoma (adamantinoma)(FIG. 16-4) [p. 883] | Multilocular radiolucent lesion with coarse inner trabeculation; it may grow very large, distorting the symmetry of the face. The condition usually is noted in patients older than 30 years of age. |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst/osteoblastomas/hemangiomas(FIG. 16-5) | Benign nonodontogenic tumors, including aneurysmal bone cysts, osteoblastomas, and hemangiomas, all producing osteolytic, expansile lesion of the mandible; each is much more common in other skeletal locations. |

| Cherubism | Bilateral, symmetric enlargement of the mandible, histologically similar to fibrous dysplasia, although the former has a familial incidence and is limited to the jaw. |

| Fibrous dysplasia [p. 846] | Unilateral, expansile, usually osteolytic, well-circumscribed lesions appearing locally or in association with other skeletal lesions. The osteosclerotic form of the disease is more typical of the maxilla. The craniofacial form (leontiasis ossea) of the disease is limited to the calvarium and face. |

| Giant cell reparative granuloma [p. 878] | Expansile osteolytic lesion of the mandible and maxilla with thin overlying cortex; this lesion is believed to represent a nontumorous reparative process. |

| Histiocytosis X (eosinophilic granuloma)(FIG. 16-6) [p. 935] | Common in the mandible; the destruction may be so advanced that the teeth appear to “float” without surrounding osseous support; Ewing’s tumor, metastatic neuroblastoma, and non–Hodgkin lymphoma may produce similar appearances of “floating teeth.” |

| Hyperparathyroidism [p. 910] | Single or multiple osteolytic lesions representing brown tumors; the lamina dura thins, as is also noted in fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease, and osteomalacia. |

| Infection | Infections of the mandible and maxilla may develop from hematogenous seeding or via direct extension from dental or sinus infection; they appear as irregular osteolytic lesions, often with accompanying sequestration; trauma and local carcinoma also have been implicated. |

| Metastasis | Osteolytic lesions similar to those of other skeletal sites; metastasis may appear secondary to hematogenous seeding or direct extension from general nasal, oral, cutaneous, or salivary gland primary lesions. |

| Multiple myeloma [p. 819] | Multiple osteolytic lesions that appear well defined and of uniform size; concomitant skull changes are present nearly always. |

| Paget’s disease [p. 946] | Diffuse osteolytic, osteosclerotic, or mixed pattern of bone disease with bilateral enlargement; concomitant skull changes nearly always occur. |

| Solitary bone cyst (hemorrhagic bone cyst) [p. 879] | Poorly defined irregular cyst of the mandible; this condition is seen in children; usually accompanied by a history of trauma. |

|

| FIG. 16-3 Three patients (A-B, C-D, and E) all with a dentigerous cyst of the right ramus of the mandible. Each appears as a radiolucency with a central radiodense unerupted tooth (arrows). |

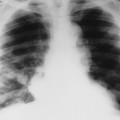

Diffuse demineralization of the skull typically is related to senile osteoporosis; however, many other conditions have classic presentations in the skull. Hyperparathyroidism mimics the radiographic appearance of osteoporosis; both appear with pure patterns of diffuse demineralization. Most of the other conditions listed in the following table produce patterns of diffuse demineralization that occur in combination with larger osteolytic lesions. For example, hemolytic anemias, leukemia, and metastatic neuroblastoma may produce a classic “hair-on-end” appearance in addition to diffuse demineralization.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Osteoporosis [p. 451] | Appears with diffuse demineralization and is typically related to aging; less commonly, osteoporosis develops from steroid supplementation or endocrinopathy. |

| Less common | |

| Anemias | Possible diffuse osteoporosis related to marrow hyperplasia caused by sickle-cell anemia and thalassemia; other findings include a “hair-on-end” appearance involving the outer table of the calvarium. |

| Hyperparathyroidism(FIG. 16-7) [p. 910] | Granular, or “salt-and-pepper,” appearance of the skull as a result of diffuse demineralization; rarely larger focal osteolytic lesions develop. |

| Infection [p. 785] | Diffuse presentation of infection is uncommon; in general, infections of the skull are less common in the United States than in underdeveloped countries. |

| Metastatic bone disease [p. 889] | Typically noted with multiple, ill-defined osteolytic lesions; this disease infrequently results in a diffuse demineralization pattern; breast, lung, and prostate origins are common in the adult; in the child, neuroblastoma and leukemia are more likely. |

| Multiple myeloma [p. 819] | Characterized by diffuse demineralization with focal “punched-out” lesions. |

| Paget’s disease [p. 946] | Diffuse demineralization that may accompany the more classic presentation of large osteolytic areas of bone destruction (osteoporosis circumscripta); demineralization occurs most often in the outer table of the skull during the lytic phase of the disease. |

Although variations exist, the sella turcica generally should not exceed an anteroposterior dimension of 16 mm or a vertical depth of 12 mm on the lateral skull radiograph. Also, normally the floor of the sella turcica is well defined by a single cortical line. The appearance of two cortical lines represents a “double-floor” sign, suggesting osseous erosion of the floor by an expansile mass. Hurler’s disease is associated with elongation of the posterior aspect of the sella, creating a J-shaped configuration.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Aneurysm of internal carotid vessel | Enlarged sella resulting from expanded cavernous segment of the carotid artery; linear vascular calcification often is present, projecting over the enlarged sella on a lateral radiograph. |

| Craniopharyngioma | Seen in children and young adults, tumor that may produce bone destruction of the sella; most lesions calcify; gliomas of the optic chiasm may cause similar changes. |

| Empty sella syndrome(FIG. 16-8) [p. 1396] | Appears as an enlarged sella without bone destruction or considerable deformity; the syndrome is believed to result from a congenital or acquired defect of the diaphragm sellae, which allows an intrasellar extension of the suprasellar arachnoid space; pulsations of the cerebrospinal fluid are thought to cause the sellar enlargement; the pituitary function typically is normal. |

| Pituitary tumors(FIG. 16-9) | Enlarged sella, uneven erosion of the floor, producing a “double-floor” appearance; pituitary tumors may be classified by size (a microadenoma is <1 cm and a macroadenoma is >1 cm in diameter) or by their appearance after staining; eosinophilic adenoma (causing acromegaly), chromophobe adenomas (causing hypopituitarism), and basophilic adenoma (causing Cushing’s disease) occur. |

| Less common | |

| Chordoma [p. 875] | Blumenbach’s clivus, representing the sloping surface of bone between the dorsum sellae and the foramen magnum (composed of the body of the sphenoid and pars basilaris of the occiput); the clivus is a target location for chordomas, which may secondarily involve the sella turcica from its posterior aspect; their appearance is marked by bone destruction and likely tumor matrix calcification; chordoma occurs most often in 30- to 60-year-old individuals. |

| Increased intracranial pressure |