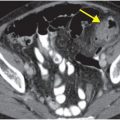

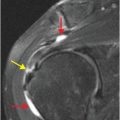

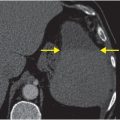

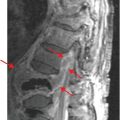

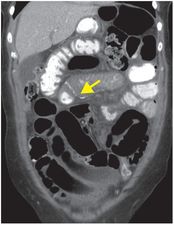

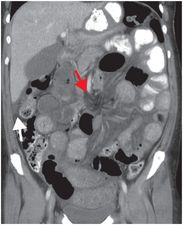

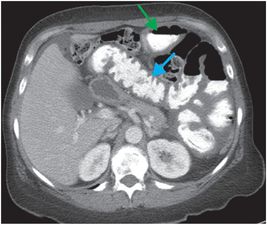

Diagnosis: Strangulated internal hernia through a Petersen defect in a patient with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

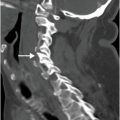

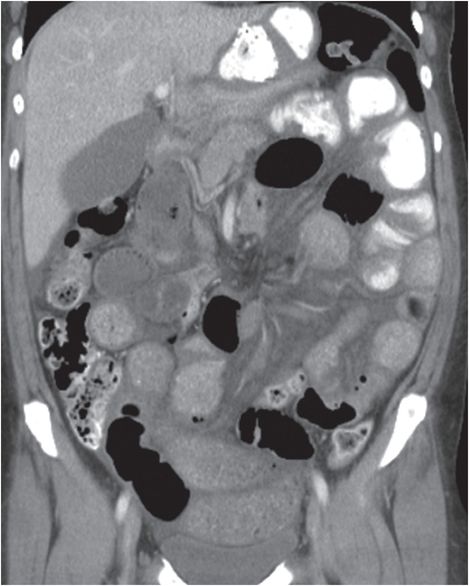

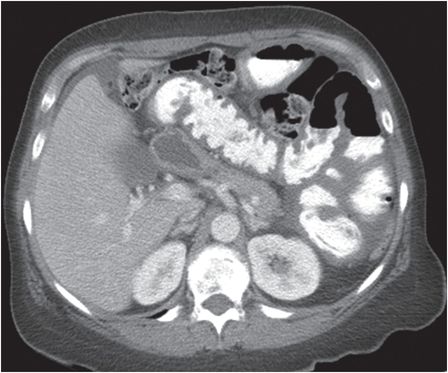

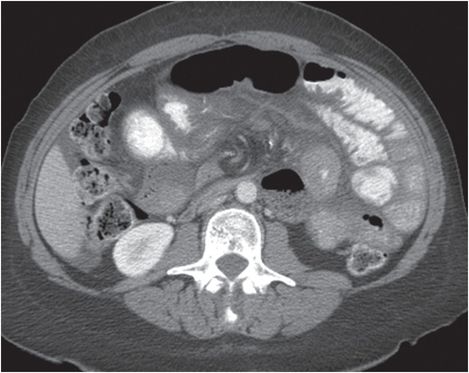

Coronal (left images) and axial (right images) CT images with oral and IV contrast show multiple dilated loops of small bowel with wall-thickening, gas–fluid levels, and free fluid, worrisome for strangulated small bowel obstruction (SBO). Internal hernia is suggested by the location of the jejunojejunal anastomosis to the right of midline (yellow arrow) and “swirling” of vessels at the root of the mesentery (red arrows). A loop of jejunum with mural thickening (blue arrow) passes posterior to the Roux limb (green arrow). Along with clustered dilated loops in the left upper quadrant, this finding suggests that internally herniated bowel has passed from right to left via a surgically created retro-Roux or “Petersen” defect posterior to the Roux limb and inferior to the transverse colon. There is trace free fluid in the subhepatic space (white arrow).

Discussion

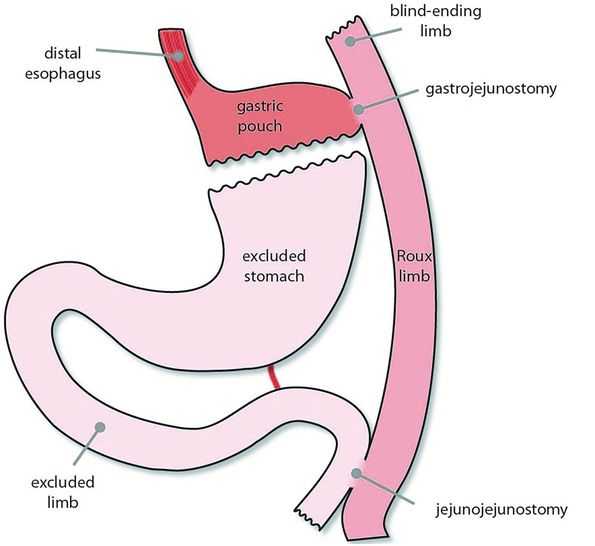

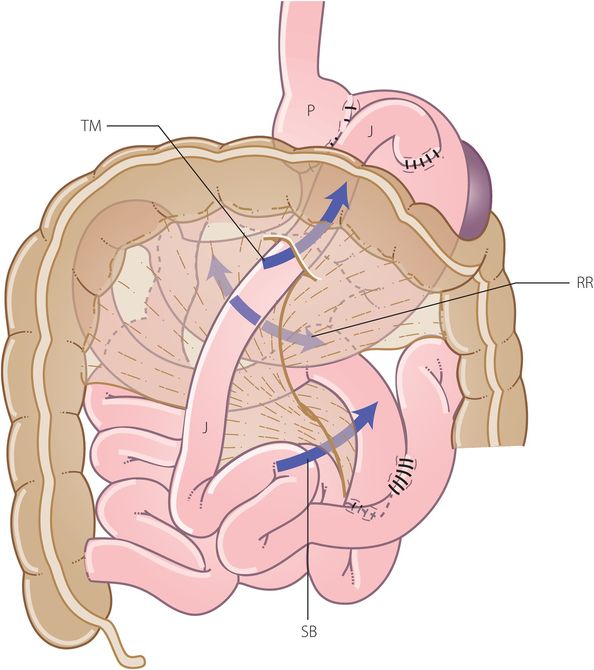

Normal post-Roux-en-Y anatomy (illustration on preceding page): in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the stomach is bisected, with a small portion of proximal stomach (gastric pouch) anastomosed to a proximally blind ending jejunal loop (Roux limb). This anastomosis is termed the gastrojejunostomy. So that biliary secretions retain a route of egress into the small bowel, the distal “excluded” stomach and duodenum (excluded or pancreatico-biliary limb) are anastomosed to the Roux limb more distally at the jejunojejunostomy. The jejunojejunostomy is typically located in the left hemiabdomen. Distal to the jejunojejunostomy, the Roux limb is in contiguity with the remainder of the bowel (common limb).

Internal hernias are increasing in incidence as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) become more common.

In both surgeries, the “Roux limb” may be placed either anteriorly (antecolic) or posteriorly (retrocolic) to the transverse colon. In the retrocolic approach, the Roux limb is passed through a surgically created defect in the transverse mesocolon. The retrocolic approach allows for a much shorter Roux limb.

Rapid weight loss from gastric bypass is thought to increase the size of the surgical defect in the fatty transverse mesocolon, predisposing gastric bypass patients with retrocolic Roux limbs to transmesocolic internal hernia.

Post-surgical internal hernias may be transmesocolic, through a mesenteric “Petersen” defect posterior to the Roux limb, or through a mesenteric defect created for the jejunojejunal anastomosis.

When incarcerated or strangulated, internal hernias are a surgical emergency.

Patients typically present with symptoms of SBO – nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain that may be postprandial. In patients with RYGB, vomiting is less common, as the volume of secretions in the gastric pouch is low relative to the volume in a normal stomach.

Internal hernias can be difficult to diagnose on imaging.

Diagnosing the type of internal hernia can be difficult, and is less important than alerting the surgeon that one is present.

The most sensitive and specific CT finding for internal hernia is the “swirled mesentery” sign, which describes rotation of vessels at the mesenteric root. One study showed that swirling of >90 degrees from anatomic position was highly associated with internal hernia, and that in all patients with swirling of >270 degrees, internal hernia was confirmed intraoperatively.

Other CT signs of internal hernia include:

The “hurricane eye” sign: similar in principle to the “swirled mesentery” sign, but more distal, with loops of bowel swirling around mesenteric fat rather than vessels in the mesenteric root.

Internal hernias after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. TM: transmesocolic; SB: defect for small bowel anastomosis; RR: retro-Roux or Petersen defect; P: gastric pouch; J: Roux jejunal limb.

Small bowel obstruction in all patients with a history of RYGB or OLT should raise high suspicion for internal hernia.

Internal hernias may occur in the absence of surgery.

The most common type of non-surgical internal hernia is paraduodenal (53%), which is congenital and more commonly to the left.

35% of transmesenteric and transmesocolic internal hernias occur in children. The likely etiology in children is a developmental insult, while surgery, trauma, and inflammation are common predisposing factors in adults.

Clinical synopsis

Given suspicion for ischemia, the patient underwent emergent exploratory laparotomy with reduction of the internal hernia. The bowel was initially felt to be ischemic but viable, so no bowel was resected. The post-operative course was complicated by abdominal compartment syndrome. Upon re-exploration 2 days after the initial hernia reduction, 150 cm of infarcted, necrotic common limb distal to the jejunojejunostomy was resected.

Self-assessment

|

|

|

|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree