Chest Radiography

Radiographic examination of the chest plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary disease. Chest radiographs account for the majority of radiographs taken each year by the medical profession. Chest radiography plays a less dominant but no less important clinical role in chiropractic practice. Although limitations exist, when combined with a thorough history and physical examination, chest radiography offers a sensitive method for detecting serious pathology of the thorax.

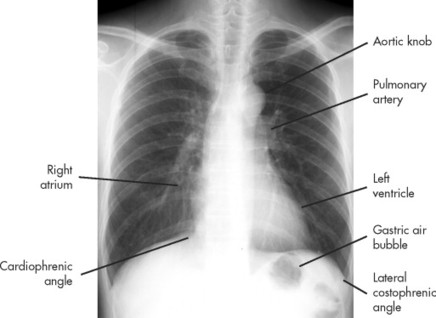

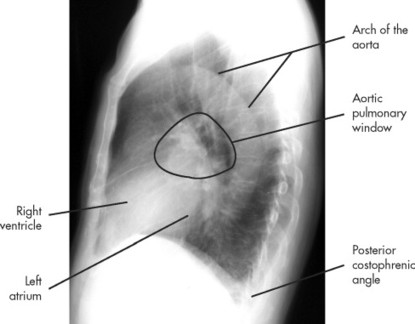

The standard radiographic examination of the chest consists of a posteroanterior (PA) and right or left lateral projection (Figs. 21-1 and 21-2). Oblique, lateral decubitus, and apical lordotic views are some of the more helpful accessory projections that may augment the standard views (Figs. 21-3 and 21-4). The lateral projection adds little as a screening procedure in the younger patient. 14 Consequently, the PA projection alone generally is accepted as adequate screening of the thorax in young individuals who are without symptoms directly referable to the chest. All patients older than 40 years of age or patients of any age who exhibit clinical findings directly referable to the chest should have both a PA and lateral projection radiograph taken during routine evaluation.

|

| FIG. 21-1 Normal posteroanterior chest. |

|

| FIG. 21-2 Normal lateral chest. |

|

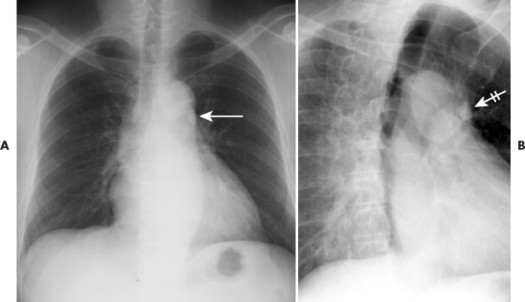

| FIG. 21-3 By providing another angle to the anatomy, oblique views may present a clearer view of pulmonary, rib, or mediastinal lesions. A, There is a small radiodense lesion overlying the shadow of the descending aorta (arrow) on the posteroanterior chest film. B, Oblique projection casts the radiodense shadow of interest laterally (crossed arrow), allowing it to be more easily seen and, in this case, confirmed as a granuloma given the homogenous calcification. |

|

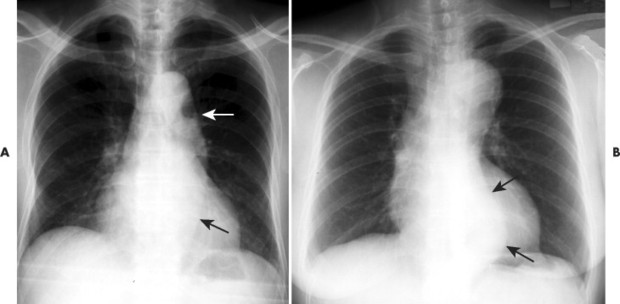

| FIG. 21-4 Apical lordotic view reduces the interpretation distraction caused by the overlying ribs and clavicle on the anatomy of the lung apices. In this case, the small tuberculosis granulomas seen on, A, the posteroanterior projection are more clearly demonstrated on, B, the apical lordotic view. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

Because the side of the body closest to the film is demonstrated with better detail and much of the left lung is obscured by the heart in the frontal projection, the left side of the body is customarily positioned next to the film in the lateral projection. 5 However, if pathology is known or suspected on the right, then the right side of the patient is placed next to the film to exhibit the area of concern with better detail.

Chest radiography employs high peak kilovoltage (110 to 150 kVp) exposures during full patient inspiratory effort, with a film-focal distance of 72 inches. In the frontal projection, rotation is present if the clavicles are not equidistant from the patient’s midline. Although individual preferences exist, generally a properly exposed chest radiograph should barely outline the thoracic spine through the heart shadow. The radiograph should display the entire thorax and particularly the costophrenic angles on the film. Good patient inspiratory result is noted by observing the posterior portions of the first 10 ribs (or anterior portions of the first 7 ribs) above the right hemidiaphragm. The right hemidiaphragm is used as a reference for the reason that the position of the left hemidiaphragm is more variable because of the subjacent gastric air bubble. Diagnostic purposes sometimes warrant taking films during patient expiration. For instance, if a “check-valve” bronchial obstruction is present, the involved lung demonstrates a pathologic state in which it remains well inflated on an expiration film.

The criteria for ordering chest films vary and often are individualized at the personal, departmental, or institutional level. Some of the more common indications include chronic cough; hemoptysis; expectoration; shortness of breath; cyanosis; clubbing of the fingers; and pain in the chest, thoracic spine, or upper extremities. Routine chest radiographs in an otherwise healthy patient population are discouraged. However, when these baseline films are available, they offer valuable comparative studies for equivocal radiographic findings on subsequent studies. Often patients exhibit residue of an old or inactive disease, such as healed granulomas, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pulmonary scarring. Frequently the availability of old films for comparison may eliminate the need for continued evaluation, limiting further cost and patient exposure. Likewise, practitioners should apply serial radiographs cautiously to follow a disease process, and then only at large enough intervals that overirradiation does not become an issue.

Many times it is necessary to augment the information gathered from the chest radiographs with other imaging modalities to more completely evaluate the patient. Fluoroscopy is an often overlooked but valuable procedure for localizing pulmonary nodules and evaluating diaphragmatic movement. Computed tomography (CT) probably is the most useful additional procedure and has all but replaced conventional tomography. CT is particularly advantageous when shadows of the chest wall, pleura, lung, hilum, or mediastinum should be better visualized when partially obstructed by overlying densities. CT is most widely used to delineate and assess neoplastic disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used most often to distinguish pathology of the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes from adjacent vascular anatomy. It has a particular advantage over CT for distinguishing mediastinal lymph node involvement from vascular masses, because flowing blood has no signal on MRI and therefore appears black, readily distinguishing vessels from the high signal intensity of the lymph nodes. The ventilation and perfusion scans of lung scintigraphy are valuable in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, although the more invasive pulmonary angiography remains the imaging standard for questionable scan results.

Although imaging examinations are valuable in the study of intrathoracic disease, they do not supplant the importance of a thorough physical examination and history. In addition, blood tests, diagnostic skin tests, sputum cultures, biopsy, and especially bronchoscopy each has the ability to add a unique information perspective to the diagnostic case. The clinician is cautioned to be cognizant of the limitations of imaging and the unique benefits provided by other diagnostic studies.

Anatomy

Selected normal structures on PA and lateral chest radiographs are identified in the normal anatomy chapter of this book (see Chapter 6). Some common variants and misinterpretations are presented in FIG. 21-5FIG. 21-6FIG. 21-7FIG. 21-8FIG. 21-9 and FIG. 21-10. The bony thorax consists of 12 thoracic vertebrae, 12 pairs of ribs with costal cartilages, and the sternum. The scapulae and clavicles are superimposed over the thorax on the PA chest radiograph. Individual muscles of the thorax generally are not discernible on radiographs. However, absence of large muscles, such as the pectorals, appears as a region of decreased density. The intercostal arteries, veins, and nerves pass along the inferior border of the ribs; enlargements of these structures may cause a characteristic erosion deformity of the inferior rib margin.

|

| FIG. 21-5 Skin overlying the clavicle (companion shadow) causes a parallel density that should not be confused with a periosteal reaction (arrows). |

|

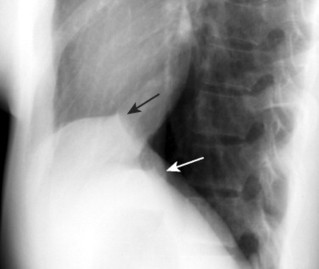

| FIG. 21-6 A and B, With advancing age, supportive tissue laxity and increased thoracic kyphosis lead to an unwinding (alternatively described as unfolding or uncoiling) of the arch of the aorta. As a result, the thoracic aorta appears lengthened and more lateral than usual (arrows). The appearance must be differentiated from an aneurysm or other mediastinal lesion. A tortuous aorta maintains the size of the vessel; therefore both the medial and lateral walls of the vessel deviate laterally together. By contrast, an aneurysm exhibits less deviation of the medial wall, defining the expanded vessel. Computed tomography may be needed to better define the appearance to exclude aneurysm. |

|

| FIG. 21-7 Sickle-shaped, concave inferior soft-tissue shadows along the upper margins of the thoracic cavity usually represent normal brachiocephalic vessels. They may be unilateral or bilateral, and often are asymmetric (arrows). For any apical shadow, prime consideration should be given to excluding a Pancoast lesion or mesothelioma. At times a similar but more focused appearance is caused by the subcostal muscles. |

|

| FIG. 21-8 Dextrocardia describes an anomalous presentation of a left-sided heart. It is usually found with reversal of other organ systems, a condition called situs inversus. Situs inversus may present as an isolated finding or as part of a larger syndrome, such as Kartagener syndrome. Kartagener syndrome describes the clinical triad of chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, and situs inversus. Deafness, infertility, and other clinical outcomes also are associated with the ciliary defects that mark this autosomal recessive syndrome. |

|

| FIG. 21-9 A tent or nipple configuration of the diaphragm correlates to the attachment of the inferior pulmonary ligaments (arrows). |

|

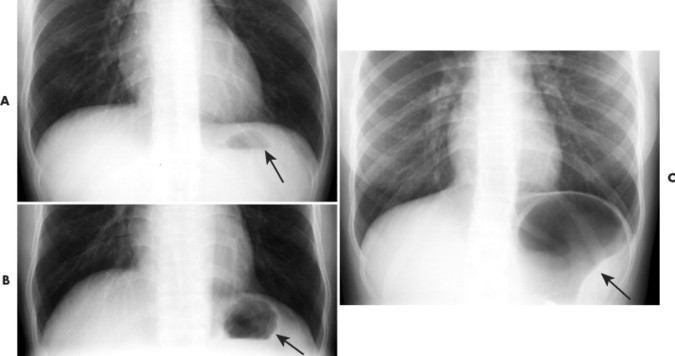

| FIG. 21-10 Gastric air bubble. The gastric air bubble (or magenblase) is located subadjacent to the left hemidiaphragm. It normally exhibits, A, a flattened hemispheric shape but can enlarge, B, slightly or, C, extensively in relation to ingestion, especially of carbonated beverages (arrows). The location of the gastric air bubble is more critical than its size. For instance, the air bubble is displaced superiorly with a hiatal hernia or may displace medially with splenic enlargement. |

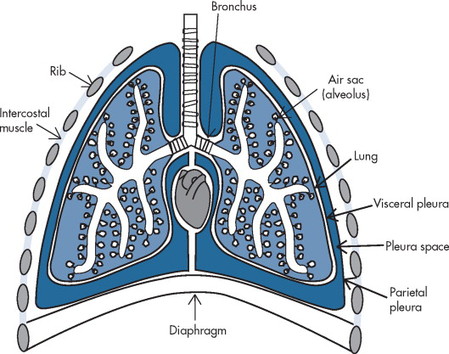

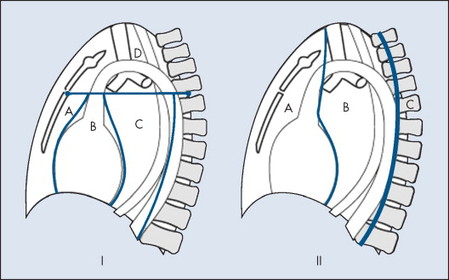

The thoracic cavity is divided into two pleural cavities surrounding a centrally located mediastinum (Fig. 21-11). The mediastinum is divided into four anatomic (superior, anterior, middle, and posterior) or three radiographic (anterior, middle, and posterior) areas, as depicted in Figure 21-12. The heart, great vessels, esophagus, thymus, and lymph tissues are all important structures contained within the mediastinum.

|

| FIG. 21-11 The thoracic cavity consists of two pleural cavities and an interposed mediastinum. |

|

| FIG. 21-12 Mediastinal divisions. I, Anatomic divisions of the mediastinum include: A, Anterior; B, middle; C, posterior; and, D, superior. II, Roentgenometric divisions of the mediastinum include: A, Anterior; B, middle; and, C, posterior. |

Visceral pleurae cover the lungs and line the pulmonary fissures; parietal pleurae line the inside of the pleural cavities. The largely potential pleural space created by these membranes may become enlarged by fluid accumulating in response to disease, known as pleural effusion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree