Diagnosis: Ischemic colitis secondary to low-flow state

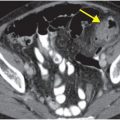

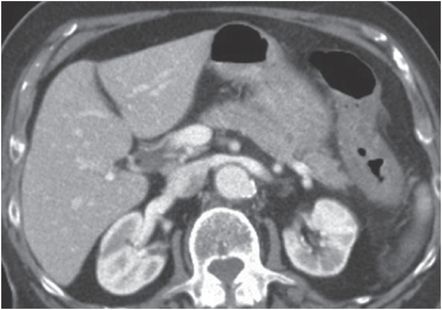

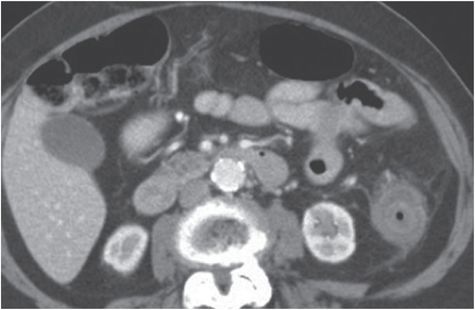

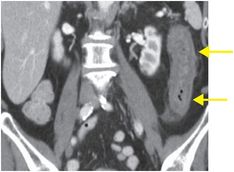

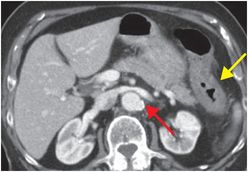

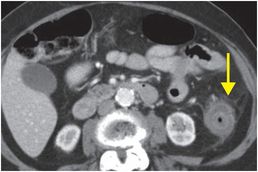

Coronal (left image) and axial (middle and right images) IV and oral contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates marked wall thickening (yellow arrows) of the descending colon from the splenic flexure (a watershed area) with adjacent fat stranding. There is atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta (red arrow) and its branches, without acute vascular cutoff.

Discussion

Overview of mesenteric ischemia

Mesenteric ischemia is caused by insufficient blood supply to the intestine and features a wide range of clinical and imaging manifestations, with a reported mortality of 50–90%.

Mesenteric ischemia may be due to numerous occlusive, nonocclusive, or mechanical etiologies.

Occlusive (thromboembolic) mesenteric ischemia is caused by arterial embolism in 85% of cases and venous occlusion in the remainder.

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia is seen in low-flow states, such as systemic hypotension or cardiogenic etiologies (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or valvular abnormalities).

Mechanical causes of mesenteric ischemia can be seen in the setting of bowel obstruction or trauma.

Less common causes of mesenteric ischemia include chemotherapeutic agents, radiation, or toxic ingestion.

Imaging of mesenteric ischemia

CT is the modality of choice to evaluate for suspected mesenteric ischemia, although the CT findings in bowel ischemia are nonspecific and can be varied, including hypoattenuating or hyperattenuating wall thickening, dilation, abnormal (or absent) mural enhancement, mesenteric stranding and ascites, pneumatosis, and portal venous gas.

The most common CT finding in acute bowel ischemia is bowel wall thickening, which is also the least specific finding.

The “double halo” sign represents enhancement of the mucosa and muscularis propria, with edema of the submucosa.

Thinning of the bowel wall or “paper-thin” wall can be seen with transmural necrosis due to loss of intestinal musculature tone.

Mesenteric fat stranding, mesenteric fluid, and ascites are other early findings of bowel ischemia, but can also be seen in infectious or inflammatory processes. Bowel dilatation with air-fluid levels may be seen as the bowel wall loses muscle tone.

Lack of enhancement of the bowel wall is a helpful, relatively specific sign of inadequate blood supply to the intestine. Pneumatosis and portomesenteric venous gas are less common but highly specific for bowel ischemia.

Mesenteric ischemia may cause hypo- or hyperattenuation of the bowel wall.

Filling defects in the mesenteric arteries and veins should be routinely sought on studies performed with IV contrast when bowel ischemia or infarction is identified. Absent or diminished flow in a mesenteric vessel is highly specific but not sensitive for mesenteric ischemia.

Clinical synopsis

The patient’s symptoms improved with bowel rest and supportive measures including IV fluids. The patient had persistent bradycardia, for which a permanent pacemaker was placed.

Self-assessment

|

|

|

|

Spectrum of mesenteric ischemia

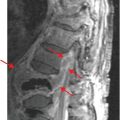

Mesenteric artery thromboembolism

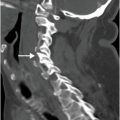

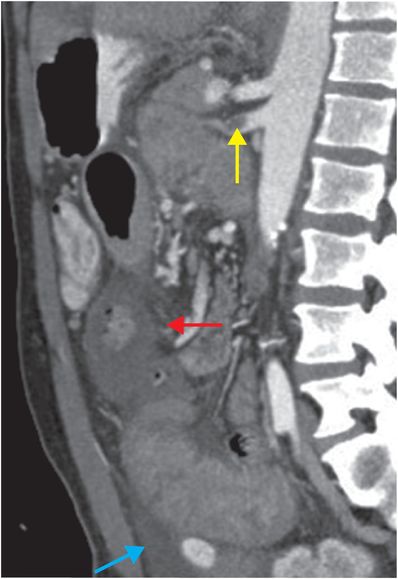

Acute occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) from thrombosis or embolization is the most common cause of acute mesenteric ischemia, accounting for approximately 60–70% of cases. The most common predisposing condition is cardiogenic thromboembolism from atrial fibrillation or ventricular aneurysm. Other etiologies include atherosclerosis, aortic thromboembolism, and aortic or mesenteric artery dissection. Sagittal CT with IV and oral contrast shows a filling defect (yellow arrow) within the proximal SMA, representing an acute thrombus. There is bowel wall thickening (red arrow) with a small amount of ascites (blue arrow).

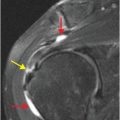

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

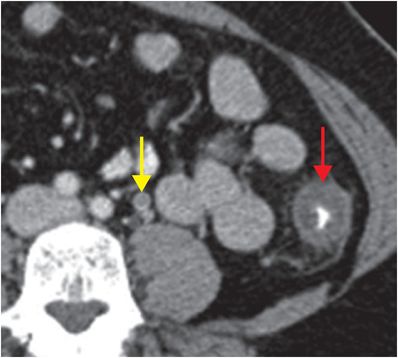

Mesenteric venous occlusion may be seen in the setting of recent surgery, neoplasm, infection, inflammation, or in other hypercoagulable states. Because of extensive collateral circulation, proximal venous thrombosis is less likely to cause severe bowel ischemia than distal venous thrombosis. Axial CT image with intravenous and oral contrast shows a hypodense thrombus in the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV; yellow arrow), with wall thickening of the descending colon (red arrow). There is adjacent mesenteric venous congestion and mild fat stranding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree