Empyema

BACKGROUND

Empyema is an intrapleural infection that is distinguished from simple parapneumonic effusions on the basis of positive cultures. The most likely infectious agents are tuberculosis or Staphylococcus, although many others have been identified. Often other radiographic evidence accompanies empyema, including pneumonia, surgery, trauma, and abdominal infections. 2,20

IMAGING FINDINGS

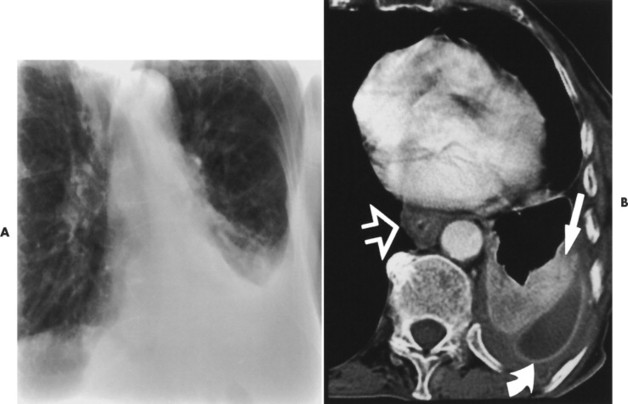

The radiographic appearance varies from a slight chest wall mass producing an inward deformity and pleural effusion to the presence of a massive radiopacity obscuring most of the hemithorax. The infective process may become extensive, encasing the lung. Computed tomography (CT) is instrumental in determining if the infection is largely pleural or pulmonary (Fig. 24-1).

|

| FIG. 24-1 A, Chest radiograph shows consolidation and volume loss of the left lower lobe. An associated left pleural effusion is evident. B, Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows consolidation of a portion of the left lower lobe (straight arrow). This is aspiration pneumonia. This patient had an esophageal hiatal hernia that resulted in a Barrett’s esophagus. Note the thickened esophageal wall (open arrow). Gastroesophageal reflux results in aspiration pneumonia. The aspiration pneumonia is complicated by a parapneumonic effusion that became infected; therefore an empyema (curved arrow). (From Swenson SJ: Radiology of thoracic diseases: a teaching file, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Fever, chills, chest pain, and other clinical findings consistent with infection typically are present. Thoracentesis may be necessary to establish the causative agent. 4 Most lung abscesses respond to appropriate antimicrobial therapy, with only about 10% requiring external drainage or surgical therapy. 39

• Empyema most often develops from pulmonary infection.

• Empyema is distinguished from pleural effusion by the presence of a positive culture.

Lung Abscess

BACKGROUND

A lung abscess is a localized suppurative process marked by tissue necrosis. It most commonly results from aspiration and bronchogenic spread of foreign material or infectious debris secondary to oropharyngeal surgery, sinobronchial infections, dental sepsis, and so on. Aspiration is common among patients who have a suppression of the cough reflex from any of a variety of reasons, including alcoholism, coma, general anesthesia, and narcotic use. Antecedent bacterial pneumonias (commonly Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae) may result in abscess formation.

IMAGING FINDINGS

When secondary to aspiration, the most gravity-dependent portions of the lung are typically involved; namely, the posterior segment of the upper lobes during an upright posture and the superior segments of the lower lobes during a supine posture. Lesions typically begin as areas of spherical consolidation. If the cavity forms a communication with the adjacent airways, the cavity’s fluid is replaced by air (Fig. 24-2), creating an air-fluid level within the once radiopaque cavity.

|

| FIG. 24-2 Pneumonia and pulmonary abscess within the right upper lobe. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The clinical presentation is characterized by cough, fever, and abundant amounts of foul-smelling, purulent, or sanguineous sputum. Chest pain and weight loss are common. Complications result if the infection extends into the pleural space. The radiographic appearance of a lung abscess should alert the interpreter of the radiograph to the possibility of bronchogenic carcinoma, which may arise in long-standing abscesses and empyemas.

• Lung abscesses are aggressive infections of the lung often secondary to aspiration of infectious debris.

• Cavitation follows a communication with the adjacent airway.

Pneumonia

BACKGROUND

Pneumonia represents inflammation of the alveolar parenchyma of the lung from a variety of causes (e.g., infections, inhalation of chemicals, and trauma to the chest wall). Unless otherwise stated, the common usage of the term pneumonia implies an infectious etiology. Pneumonias are classified by their causative organism (e.g., virus, bacteria, mycoplasma, yeasts, or fungi), radiographic appearance (lobar, lobular or bronchostitial, interstitial, and spherical or round), or etiology (community-acquired, nosocomial, immunosuppressed, or aspiration).

Infections are transmitted to the lung parenchyma by one or more of the following pathways: direct extension, hematogenous spread, inhalation of airborne agents, and aspiration of gastric or nasopharyngeal organisms. The characteristics of selected pneumonias are presented in Table 24-1.

| Causative agent | Comments |

|---|---|

| Bacterial (gram-positive) | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae, pneumococci) | Most common bacterial community-acquired agent35 and common hospital-acquired pneumonia; it occurs at any age; prototype lobar pneumonia appears as homogenous consolidation; 16 children often demonstrate spherical pattern |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) | Seen rarely today, although common in early 1900s; appears as homogenous consolidation, typically of lower lobes; often it is accompanied by large pleural effusion and empyema5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) | Commonly results from aspiration of gastric contents; patchy segmental consolidation; cavitation, pneumatoceles, pleural effusion, and empyema are common |

| Anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) | Uncommon in the United States, typically acquired in the Middle East from contact with infected goats; it produces patchy consolidation of the lower lungs with occasional mediastinal widening because of lymphadenopathy38 |

| Bacterial (gram-negative) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae, Friedländer’s disease) | Typically affects individuals with chronic debilitating disease or alcoholism; it appears as homogenous nonsegmental consolidation, often rapidly progressing to involve the entire lobe; 17 regions of lung involvement may appear expanded14,21 |

| Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila) | Found in aquatic environments (humidifiers, water towers, reservoirs, etc.); radiographic appearance begins as patchy peripheral densities, rapidly progressing to involve the entire lobe; 12 pleural effusion often is noted |

| Pertussis (Bordetella [Haemophilus] pertussis) | Marked by streaking peribronchial consolidation in one or more lobes; 3,4 a tendency exists to involve the right lung to a greater extent |

| Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) | Common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 6 alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus, as well as children; 37 it exhibits a lower lobe bronchopneumonia pattern; H. influenzae is often concomitant with empyema, meningitis, or epiglottitis |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) | Common in hospitalized ventilated patients with lowered immunity; it appears as extensive, bilateral, ill-defined opacities in the lower lobes, often with small pleural effusion22 and abscess formation |

| Mycobacterial | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) | Distribution largely impacted by social and economic factors; few patients demonstrate signs or symptoms with primary infection; secondary infections are marked by clinical symptoms and radiographic changes in the lung parenchyma, tracheobronchial tree, and hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes |

| Mycoplasmal | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) | Exhibits bacterial and viral characteristics; this type generally is recognized as the most common nonbacterial cause of pneumonia; 15 it appears similar to viral pneumonias with primarily an interstitial pattern in the early stages of the disease, 9 possibly progressing to an air-space pattern |

| Viral | |

| Influenza (Groups A, B, and C) | Usually confined to the upper respiratory tract, rarely produces pneumonia; when present appears as patchy, bilateral lower lobe consolidation; localized consolidation occurs less commonly |

| Varicella-zoster | Affects immunosuppressed patients or may complicate lymphoma; the radiographic appearance of acute disease appears as patchy diffuse air-space consolidation; 34 a less common presentation consists of multiple 5- to 10-mm diffusely scattered bilateral radiopacities that have a tendency to calcify8 |

| Fungal | |

| Actinomyces israelii (A. israelii) | Represents normal inhabitant of oropharynx; infection results when organism reaches devitalized tissue and proliferates; mandibular infection may complicate dental extractions; pulmonary infection develops from direct extension or aspiration of infectious debris; it appears as peripheral lower lobe air-space consolidation |

| Histoplasma capsulatum (H. capsulatum) | Endemic to the Mississippi, Ohio, and St. Lawrence River valleys and Puerto Rico; the majority of infections are asymptomatic with a past presence suggested by multiple scattered discrete calcific densities with (or without) accompanying calcified hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes; chronic involvement of the mediastinum may lead to fibrosing mediastinitis |

| Coccidioides immitis (C. immitis) | Endemic to the southwest United States (San Joaquin Valley); infected individuals may describe arthralgias and erythema nodosum (valley fever); imaging findings include well-defined segmental radiopacities that typically resolve over time; mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy may be present; the chronic progressive form of the disease is similar to postprimary tuberculosis or histoplasmosis |

| Aspergillus fumigatus (A. fumigatus) | Presents as aspergilloma (“fungal ball” or “mycetoma”), representing a mass in a preexisting pulmonary cavity; more invasive varieties of parenchymal infection are seen in the immunocompromised patient41 |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis (B. dermatitidis) | Chronic systemic infection that appears as nonsegmental homogenous consolidation with a tendency to involve the upper lobes of the lung; less commonly it presents as single or multiple mass lesions19 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans; formerly Torula histolytica) | Worldwide distribution; infection results from inhalation of contaminated dust; a wide variety of radiographic presentations exists; it is associated with lymphomas, steroid therapy, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); meningitis and encephalitis represent the most serious complications; the most common radiographic appearance is a single well-defined nodule or mass, 18 less commonly a region of consolidation13 |

| Parasitic | |

| Pneumocystis carinii (P. carinii) | Significant pneumonia among immunocompromised patients (e.g., AIDS and organ transplant patients), demonstrates bilateral perihilar fine, “ground-glass” radiographic appearance; 30 it may progress to air-space consolidation pattern; pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy are uncommon |

| Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosis—infection called hydatid disease) | Tapeworm whose definitive host is dogs and intermediate host is sheep; when humans become the accidental intermediate host, disease results; pulmonary involvement is marked by a well-defined, three-layered pulmonary mass7 or cyst, most often in the lower lobes; rupture of the cyst may produce a radiodense air shadow (“crescent” sign) or noticeable floating debris on the internal fluid of the cyst (“water lily” sign) |

IMAGING FINDINGS

Chest radiography remains the primary tool to establish the presence and extent of pneumonia. Although it should be emphasized that the lack of radiographic evidence does not exclude pneumonia, neither does the presence of consolidation exclusively indicate the presence of pneumonia. It is imperative that clinical findings be correlated to the radiographic appearance.

Although large areas of crossover exist, several radiographic patterns of lung infection have been identified (Table 24-2). However, except for a few classic presentations (Table 24-3), the radiographic appearance of most lung infections is so general that radiographs offer little help in isolating a particular causative agent. 36

| Radiographic type | Radiographic appearance |

|---|---|

| Broncho (lobular) pneumonia | Represents the most common pneumonic pattern, in which inflammatory exudate involves some and spares some of the parenchymal tissue along a large airway; it appears as fluffy, patchy, multifocal densities tracking along a large airway; because the airways are affected, there may be volume loss, and air-bronchograms are uncommon; common agents include S. aureus, H. influenza, gram-negative bacteria |

| Lobar pneumonia | Inflammatory exudate beginning in the periphery of the lung and spreading circumferentially through pores of Kohn and canals of Lambert to involve adjacent lung tissue, involving the entire bronchopulmonary segment and eventually lobe; the region of pneumonia appears homogenously radiodense; because the airways are not involved, volume loss is rare and air bronchograms are common; common agents include S. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus |

| Interstitial pneumonia | Localized or generalized thickening of the interstitium producing peribronchial or reticulonodular radiographic patterns; typically it is caused by viral or mycoplasma infections |

| Aspiration pneumonia | Bilateral, poorly defined consolidation in gravity-dependent portions of the lung |

| Radiographic appearance | Organisms |

|---|---|

| Consolidation of all or nearly all of a lobe | Bacteria |

| Consolidation with cavitation or pneumatoceles | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Consolidation with expansion of the lobe | Klebsiella pneumoniae (see Fig. 24-15) |

| Spherical (nodular) pneumonia | Pneumococcal, 33Legionella micdadei,31 and Q fever28 |

| Localized or widespread reticulonodular pattern | Viruses10 or mycoplasma |

| Miliary nodules | Tuberculosis, fungi, or varicella-zoster |

| Patchy upper lobe consolidations | Tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, etc. |

| Large pleural effusions | S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes |

The essential radiographic finding of pneumonia is partial or complete lung consolidation, often with associated pleural effusion, a silhouette sign, air-bronchogram, lung cavitation, and empyema (FIG. 24-3FIG. 24-4FIG. 24-5FIG. 24-6FIG. 24-7FIG. 24-8FIG. 24-9FIG. 24-10FIG. 24-11FIG. 24-12FIG. 24-13FIG. 24-14FIG. 24-15FIG. 24-16 and FIG. 24-17). Selected causative agents and their radiographic appearances are presented in Table 24-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree