Bronchogenic Carcinoma

Hamartoma

Lymphoma

Metastatic Lung Disease

Pleural Mesothelioma

Teratomas

Thymic Masses

Bronchial Carcinoid Tumors

BACKGROUND

Bronchial carcinoid tumors are uncommon pulmonary tumors, formerly termed bronchial adenomas. The term adenoma to describe these lesions is a misnomer resulting from their locally invasive nature, tendency for recurrence, and occasional metastasis to extrapulmonary tissues. They typically occur in patients at least 40 years of age but represent the most common primary lung tumors in patients under the age of 16 years. These tumors arise from neuroectodermal cells49,68 and are hormonally active, known to produce symptoms similar to Cushing’s disease. 22,25 Overall, 75% arise in the lobar bronchi, 10% in the mainstem bronchi, and 15% in the periphery of the lung. 18 Ninety percent of bronchial carcinoids are well-differentiated lesions. Atypical carcinoids are less common but exhibit a higher malignancy rate than well-differentiated lesions.

IMAGING FINDINGS

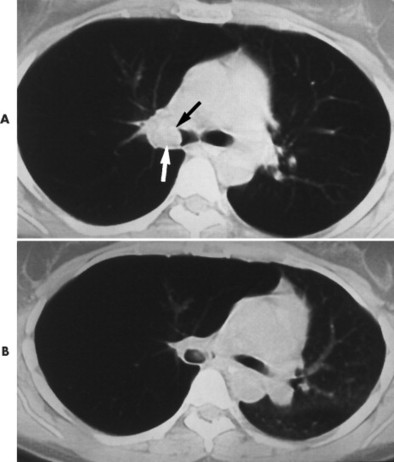

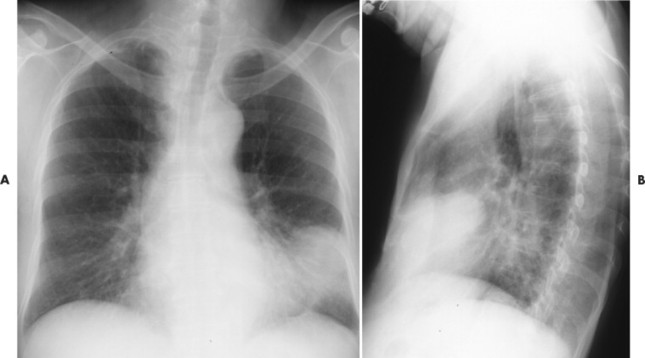

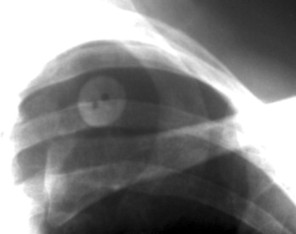

Often a solitary nodule can be seen on plain films. This is more likely if the lesion is peripherally located. Bronchial carcinoids commonly are discovered by recognizing associated findings of bronchial obstruction. If the airway obstruction is partial, a checkvalve obstruction may result in overexpansion of the distal air-space. Atelectasis results if obstruction is complete. Recurrent pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and calcification of the lesion also may occur. 6 Computed tomography (CT) is helpful in confirming suspected lesions (Fig. 25-1).

|

| FIG. 25-1 A, Computed tomography (CT) shows an endobronchial tumor in the right mainstem bronchus (arrows). B, CT performed after exhalation shows a significant mediastinal shift to the patient’s left as a result of air trapping on the right. (From Swenson SJ: Radiology of thoracic diseases: a teaching file, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Because bronchial carcinoid tumors commonly are centrally located in the lobar divisions of bronchi, they often present with findings related to bronchial obstruction (recurrent atelectasis and pneumonia). Clinical findings of hemoptysis, wheezing, cough, and atypical asthma may be noted. A small percentage of patients remain asymptomatic. Resection is typical, with a 5-year survival rate of 95%. The prognosis is usually excellent and is more specifically determined when the pathologic grade and stage of the tumor are known.

• Bronchial carcinoid tumors are low-grade malignancies most commonly arising in the lobar bronchi.

• Well-differentiated carcinoid tumors represent almost 90% of all bronchial carcinoids.

• Lesions may be seen directly on radiographs or often are found by recognizing concurrent findings of airway obstruction. Resection usually is associated with an excellent prognosis.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

BACKGROUND

Risk factors.

Bronchogenic carcinoma (lung cancer) was a relatively uncommon tumor at the beginning of the century. It has grown to become the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men and women. Lung cancer accounts for approximately 20% of cancer deaths among men and 10% among women, replacing breast cancer as the most common cause of cancer death among women. 44 Cancer rates correlate positively with population density, chronic lung disease, urbanization, industrialization, cigarette smoking, and carcinogenic inhalants (e.g., asbestos, nickel, uranium, chromates). 21,69 Genetic factors seem to play a role in the development of lung cancer, but the influence is confounded by environmental factors such as cigarette smoking.

Cigarette smoking is the most common important risk factor for developing lung cancer, with approximately 90% of lung cancer worldwide attributed to cigarette smoking. Its development is related to both the duration and dose of cigarette smoking, with risk of lung cancer death reported in the realm of 12 to 20 times that of nonsmokers. Although rates of smoking among men appear to have leveled off, smoking among women has increased7 and is likely to be responsible for the contemporary increase in lung cancer rates among women. The risks of smoking may be compounded when other risks are present. For instance, asbestos exposure alone relates approximately five times the baseline risk for developing lung cancer; however, the combination of work-related asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking is associated with a 50 to 100 times baseline risk, a synergistic risk that far exceeds the risk derived by simply adding the risks of the individual factors.

Bronchogenic carcinomas develop from the airways, not the lung parenchyma. Parenchymal neoplasms are represented by leiomyomas, fibromas, chondromas, and other mesenchymal derivatives. 60 Bronchogenic tumors are divided into four groups, based on histology: squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and small (oat) cell carcinoma (Table 25-1). 33,51 Bronchoalveolar carcinoma is a subtype of the adenocarcinoma cell type. 14

| *Considerable crossover exists in radiographic appearance, making distinction among types difficult. | |

| Type | Radiographic appearance* |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma | Most often a central lesion with locally invasive hilar and mediastinal involvement, often presenting as lobar collapse; peripheral presentation appears as nodule, mass, or cavity |

| Adenocarcinoma | Most common cell type, nearly always presents as peripheral mass; smaller in size than large cell type |

| Alveolar cell carcinoma (bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma) | Subtype of adenocarcinoma, most commonly presents as a nodule, but is more noted for its presentation of diffuse or localized air-space disease pattern |

| Small (oat) cell carcinoma | Classically presents as a hilar or mediastinal metastasis, whereas the primary tumor remains occult; it is the most aggressive cell type, having the worst prognosis; central involvement may lead to atelectasis or superior vena cava syndrome |

| Large cell carcinoma | Like adenocarcinoma, presents in a peripheral location, but is most often larger in size than adenocarcinoma cell type |

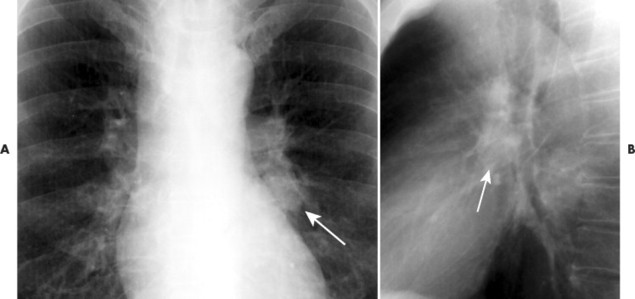

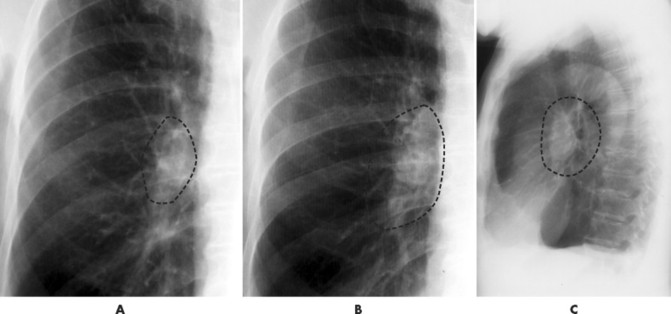

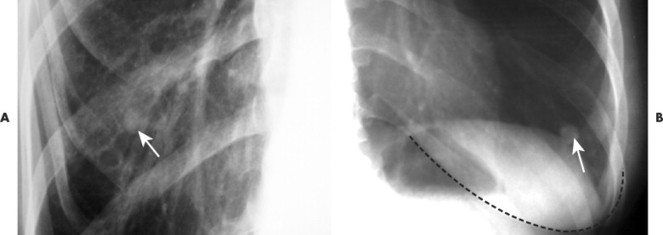

Often lesions are divided by location into central (near the hilum) or peripheral (lateral to the hilum) location (FIG. 25-2FIG. 25-3FIG. 25-4FIG. 25-5FIG. 25-6FIG. 25-7FIG. 25-8FIG. 25-9FIG. 25-10 and FIG. 25-11). Peripheral lesions appear as masses (>3 cm diameter) or nodules (≤3 cm diameter) 26 in the lateral lung field arising from the third or fourth order bronchi and beyond. Central lesions arise from the mainstem, lobar, or segmental bronchi and appear as hilar enlargements or present with secondary findings related to airway obstruction. Approximately 60% of lesions are central and 40% are peripheral. 4 Sixty percent of lesions (peripheral and central) are right sided. Similarly, 60% of peripheral lesions are in the upper lung (Fig. 25-12), 30% in the lower, and the remaining 10% in the middle and lingual segments. The average age of patients with recently recognized lung cancer is 53 years, with 80% of lesions developing between 40 and 70 years. 66

|

| FIG. 25-2 A and B, Central bronchogenic carcinoma of the patient’s left hilum (arrows) in a 59-year-old male patient. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 25-3 Bronchogenic carcinoma presenting as an enlarged hilum. Normally the hila are well defined and exhibit a branching pattern that is absent in this example. |

|

| FIG. 25-4 Bronchogenic carcinoma enlarging the hilum. A, First film exhibiting an abnormal bulky appearance of the hilum. B, Second film taken 4 months later revealing that the lesion has grown. C, Lesion in the right hilum, as noted by its appearance anterior to the bronchi in the aortic pulmonary window of the lateral projection. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 25-5 At times a large hilar vessel may be confused with a pulmonary nodule. One clue to differentiation is provided by the observation that pulmonary vessels and bronchi follow a similar branching pattern. Therefore if a radiodense ring shadow accompanies the suspicious homogeneous radiodense shadow, the apparent nodule is likely a vessel, not a true pulmonary nodule. This finding of a radiodense circle (arrow) next to a radiodense ring (with radiolucent center) (crossed arrow) is known as a monocle sign. |

|

| FIG. 25-6 Large malignant mass presenting behind the heart shadow (arrows). A, Pulmonary lesions presenting behind and in front of the heart are missed easily. B, Care should be taken to look closely through the heart shadow and augment this difficult-to-interpret area with the addition of a lateral view. (Courtesy Gary Longmuir, Phoenix, AZ.) |

|

| FIG. 25-7 Bronchogenic carcinoma presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule without evidence of calcification (arrow) in a 56-year-old man. The lack of calcification necessitates further evaluation to exclude malignancy in middle-aged and older patients. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 25-8 Large malignant mass in the patient’s lower right lung (arrow). |

|

| FIG. 25-9 A and B, Bronchogenic carcinoma in a 70-year-old male patient. The lesion presented as a large noncalcified mass. The larger a lesion, the more likely it is malignant. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

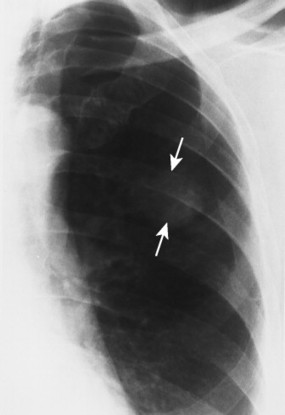

| FIG. 25-10 Squamous cell bronchogenic carcinoma presenting as a noncalcified solitary pulmonary nodule at the level of the posterior angle of the sixth left rib (arrows). (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

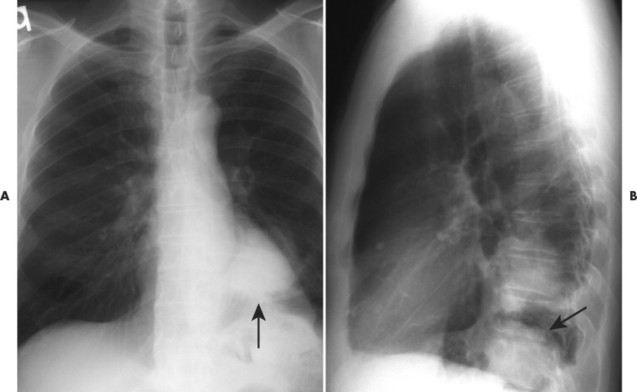

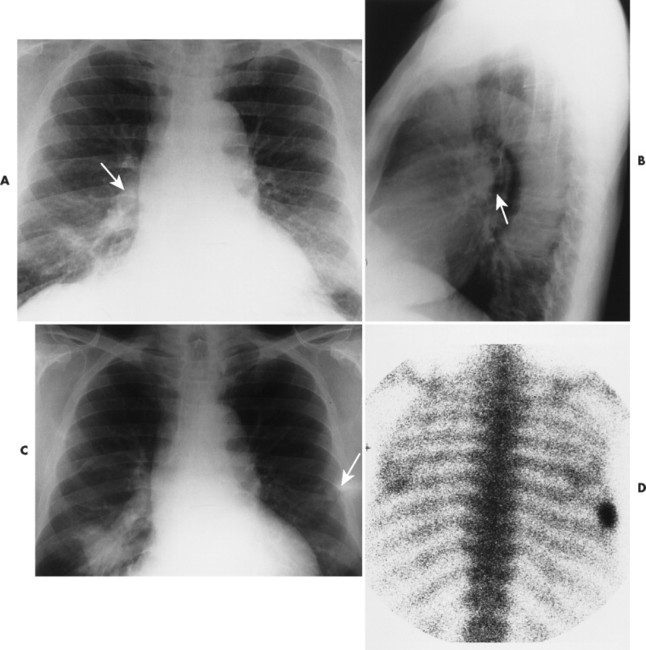

| FIG. 25-11 A, Bronchogenic carcinoma presenting on the initial film with pulmonary infiltrate of the right lung field with enlargement of the right hilum (arrow). B, Lateral projection revealing radiodense region in the aortic pulmonary window corresponding to the right hilum (arrow). C, Thirteen months later the pulmonary infiltrate has consolidated into a mass. Also of interest is an unrelated fracture of the lateral margin of the seventh left rib (arrow). D, Radionuclide bone scan demonstrating radionuclide uptake at the fracture site. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 25-12 Apical lordotic projection demonstrating noncalcific mass in the right lung apex, consistent with bronchogenic carcinoma. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

IMAGING FINDINGS

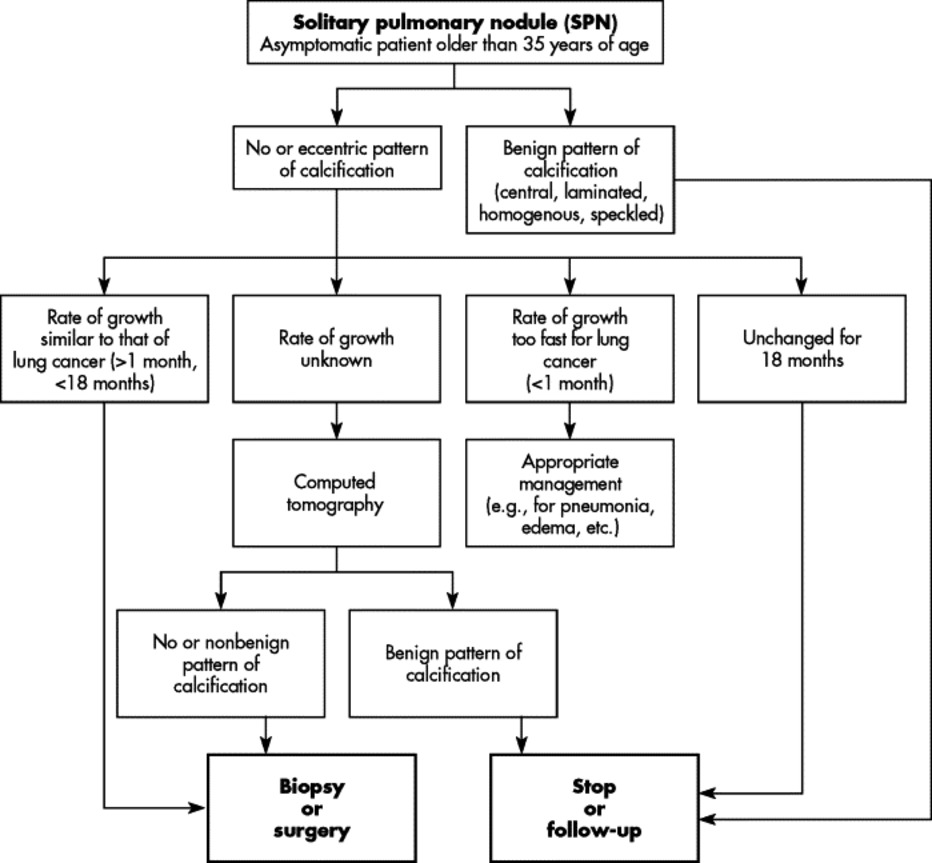

The radiographic features of a nodule or mass are important to the clinical management of the patient. When considered with the patient age, the growth rate, calcification, size, and location of the lesion are significant indicators of a benign versus malignant lesion (Fig. 25-13). Associated bone destruction is a strong indicator of malignancy (Figs. 25-14 and 25-15).

|

| FIG. 25-13 Management algorithm of solitary pulmonary nodules of patients in cancer age group, based on imaging findings. |

|

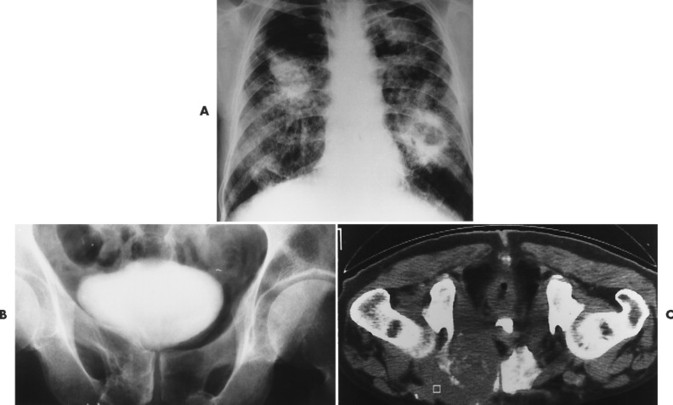

| FIG. 25-14 A, Cavitating squamous cell carcinoma of the left lower lung field in a patient with progressive massive fibrosis noted by the bilateral, asymmetric radiodensities in the lung fields. B, Plain film radiograph and, C, computed tomography scan reveal lytic bone destruction of the right pubis resulting from metastasis of the lung carcinoma. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

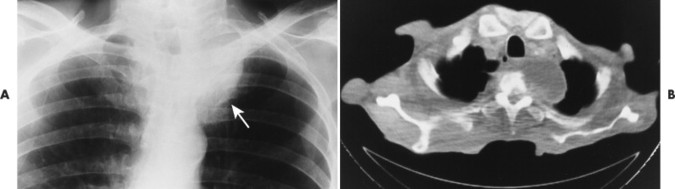

| FIG. 25-15 A, Bronchogenic carcinoma within the medial portion of the patient’s left lung apex (Pancoast tumor) (arrow). B, Computed tomography reveals the tumor mass with associated vertebral body destruction. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

Location.

Central tumors demonstrate radiographic changes related to airway obstruction. Airway obstruction leads to volume changes presenting as atelectasis or overinflation (if a check-valve mechanism develops), both of which may displace the mediastinum, heart shadow, diaphragm, or other anatomic borders. A consolidated radiographic pattern may result from postobstructive pneumonitis, which refers to marked retention of lung secretions in the alveolar spaces secondary to airway obstruction. 9.

An enlarged hilum is a common finding of central tumors. 56 The enlarged hilum represents the tumor mass itself or associated lymph node involvement. A classic radiographic appearance, known as the S-sign of Golden, develops when the hilar mass is found with concurrent radiopacity of the right upper lobe secondary to either atelectasis or postobstructive pneumonitis resulting from airway obstruction. The inferior border of the parenchymal radiopacity appears as a smooth, reversed S-shape. The radiographic appearance appears S-shaped when present on the patient’s left side.

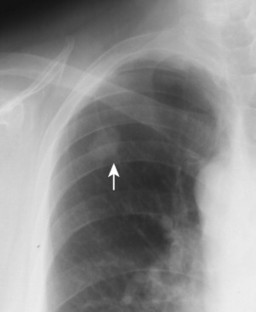

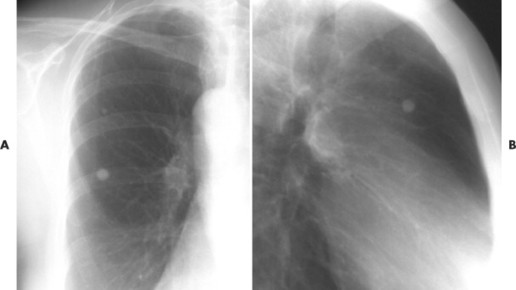

Pancoast (superior sulcus) tumors are defined as dense, homogenous masses with smooth borders located in the lung apex (FIG. 25-16FIG. 25-17 and FIG. 25-18). Lesions often demonstrate adjacent rib or vertebral destruction (see Fig. 25-15). Most Pancoast tumors are caused by squamous cell carcinomas, although other types of bronchogenic tumors may be responsible. Alternatively, Pancoast tumors may appear with little more than subtle pleural thickening.

|

| FIG. 25-16 Bronchogenic carcinoma presenting as a right apical mass. |

|

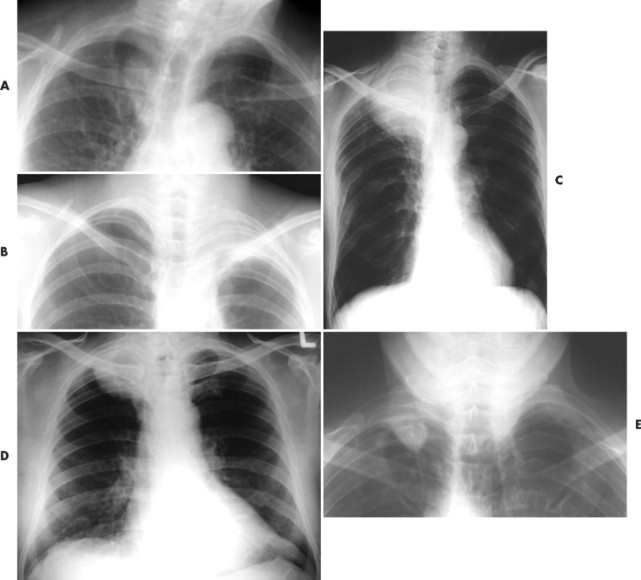

| FIG. 25-17 A through E, Different patients with Pancoast tumors. Pancoast tumor is a nickname for lung cancer presenting in the lung apex. Pancoast lesion may present clinically with Horner syndrome, upper extremity neurovascular compromise, and rib destruction. (A and B, Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY; C and D, Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

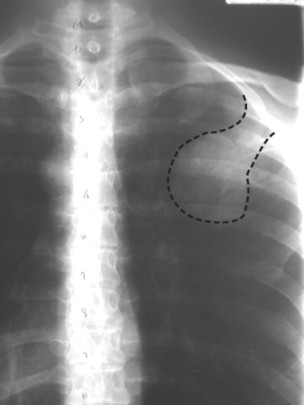

| FIG. 25-18 Care should be taken not to underinterpret the apices of the lungs on an anteroposterior lower cervical radiograph. As seen here in the patient’s left lung apex, Pancoast tumors are common serious pathologies that may present in this radiographic view. (Courtesy Gary Longmuir, Phoenix, AZ.) |

Size.

Peripheral lesions often present as only a spherical radiopacity. 10 Lesions present in variable sizes, but they are difficult to detect on plain films if less than 1 cm in diameter. 28,42 The average diameter at the time of discovery is 5 cm. 66 Lesions greater than 3 cm in diameter are malignant 85% of the time. 53 Most solitary pulmonary nodules (lesions ≤3 cm in diameter) are indeterminate at the time of discovery. Further procedures (CT, biopsy, and thoracotomy) are necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis. 30

Nipple shadows, moles, and other body wall lesions may mimic pulmonary nodules, particularly in the periphery of the lung (FIG. 25-19FIG. 25-20FIG. 25-21 and FIG. 25-22). Repeating the radiograph with metallic markers over the area in question is a simple method to exclude such body wall lesions (Fig. 25-23).

|

| FIG. 25-19 Apparent pulmonary mass that latter studies confirmed was a benign lesion of the rib, likely an osteochondroma. (Courtesy C. Robert Tatum, Davenport, IA.) |

|

| FIG. 25-20 A, The small radiodense shadow appears to be in a pulmonary location. B, However, the lateral view and patient examination confirm it as large a mole (arrows). (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 25-21 A button mimics a solitary pulmonary nodule. In this case the two holes in the center of the shadow readily confirm it as a clothing artifact. |

|

| FIG. 25-22 At times, A, a male or, B, female patient’s nipple (arrows) may be confused as a solitary pulmonary nodule. The nipple often appears more well defined laterally from better air contrast when the medial side of the nipple is pushed against its adjacent soft tissue as a result of placing the anterior chest wall against the grid cabinet during the posteroanterior chest patient setup. Also, the nipple shadow often is bilateral and generally is found in an expected anatomic location relative to the breast shadow that also may be seen on the film. If differentiation between the nipple shadow and pulmonary nodule cannot be made, a metallic marker is placed over the nipple and the chest x-ray is repeated (see Fig. 25-23). |

|

| FIG. 25-23 Paper clips confirming that nipple shadows represent bilateral symmetric pulmonary nodules. In addition, a bronchogenic carcinoma is in the apex of the patient’s right lung (Pancoast tumor) causing the radiodense shadow above the patient’s right clavicle. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

Borders.

The appearance of the outer border of the lesion has been emphasized in the past. Circumferential strandlike radiopacities radiating from the outer border of the tumor (corona radiata) have been described71 as characteristic but not specific to bronchogenic tumor. 35 The irregular outer border is believed to represent tissue fibrosis or radial spread of the tumor. A lobulated appearance of the outer border, representing areas of rapid growth, is found in 50% of peripheral tumors. Cavitation has been described in 16% of peripheral lesions, 66 most often seen in the squamous cell type.

Calcification.

Calcification of bronchogenic tumors rarely is demonstrated on plain film studies. CT demonstrates calcification in 6% to 7% of lesions. 45,73 As depicted in Figure 25-24, certain patterns of calcification strongly suggest a benign etiology. Central, laminated, or total homogeneous calcification is typical of granulomas. A “comma-shaped” or “popcorn” calcification pattern suggests a hamartoma. Eccentric calcification is associated with bronchogenic carcinoma, representing calcium produced by the tumor, dystrophic calcification of ischemic tissue, or a granuloma that has been engulfed by the growing tumor mass. Patients who demonstrate masses and nodules with no calcification or calcification only in the periphery of the lesions should be studied vigorously for the possibility of malignancy (FIG. 25-25FIG. 25-26FIG. 25-27FIG. 25-28FIG. 25-29FIG. 25-30 and FIG. 25-31).

|

| FIG. 25-24 Benign patterns of nodule calcification. A, Central; B, homogenous (total); C, laminated; D, amorphous; and E, speckled. |

|

| FIG. 25-25 A and B, Isolated small densely calcified nodule consistent with a benign etiology. (Courtesy Julie-Marthe Grenier, Davenport, IA.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree