27 Image-Guided Colorectal Obstruction Management

Horacio R. V. D′Agostino, David H. Ballard, Paul A. Jordan, Kenneth Manas, Antonio Mainar, and Miguel A. De Gregorio

27.1 Introduction

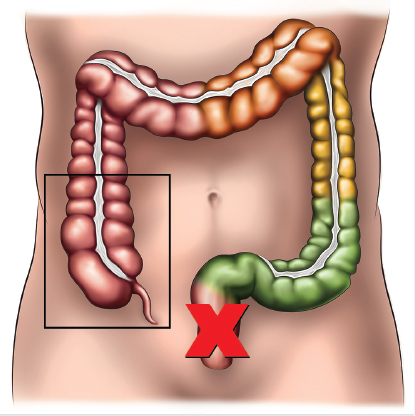

Benign or malignant acute colorectal obstruction is typically managed with emergency surgery. For patients who can tolerate the procedure, right colonic obstruction is managed with a right conventional or extended colectomy. Surgery for acute left colonic obstruction usually consists of an operation that may include resection and creation of an ostomy. Despite advances in ostomy care, avoidance of the colostomy is still desirable, as the presence of an ostomy affects patient well-being. A colostomy is also associated with increased morbidity at the time of the procedure and when the colostomy is reversed. The additional surgery required for colostomy closure leads to a prolonged hospital stay and an increase in the overall costs for colonic obstruction management.

Currently, transanal stent placement is a mainstream procedure used to manage colonic obstruction. The complexity of deploying a colonic stent is influenced by the location of the obstructive lesion, the length of intestine involved, and the presence of complications such as associated fistula or small bowel obstruction. Lesions located in the left colon from the rectosigmoid junction up to the splenic flexure are the most amenable for transanal stent placement. In cases of colonic obstruction that are not amenable for surgery and cannot be managed by retrograde placement of a stent, a decompressive percutaneous cecostomy is indicated (▶ Fig. 27.1, ▶ Fig. 27.2).

In this chapter, we focus on percutaneous cecostomy and transanal stent placement for image-guided management of colonic obstruction. Percutaneous cecostomy is generally performed by interventional radiologists. However, as with many other procedures initiated by interventional radiologists, colonic stent placement is currently performed by gastroenterologists and surgeons, as well. In an ideal situation, interventional radiologists, gastroenterologists, and surgeons can work together to manage cases of colonic obstruction, combining their expertise to provide optimal patient care.

27.2 Percutaneous Cecostomy

27.2.1 Background

Percutaneous cecostomy consists of percutaneous insertion of a catheter through the anterior abdominal wall within the lumen of the cecum to decompress distal colonic obstruction. This procedure is often used in cases that are not amenable for surgery or in which transanal stent placement has failed. Occasionally, another limb of the colon (e.g., right or transverse colon) will be more accessible, and these sites can be accessed in a manner similar to that used in percutaneous cecostomy; in such cases, the procedure is termed percutaneous colostomy. 1

Percutaneous cecostomy was first described in 1986 by Casola et al 2 in a case of massive cecal dilatation secondary to obstruction; in this case, lower endoscopy could not traverse the obstruction. A subsequent report in 1987 by Haaga et al 3 described the use of percutaneous cecostomy for decompression of Ogilvie′s syndrome (▶ Fig. 27.3). The indications and uses for this procedure subsequently expanded, and this technique is now considered an effective treatment for neurogenic motility disorders causing chronic constipation with overflow fecal incontinence, chronic nonobstructive colonic dilatation (e.g., Ogilvie′s syndrome), and refractory cases of large bowel obstruction. 1 , 4 , 5 When percutaneous cecostomy is used for chronic constipation with overflow fecal incontinence (typically in patients with a central neurologic disease such as spina bifida), the catheter is used for elective anterograde enema flushes. In this chapter, we focus on the use of percutaneous cecostomy for the treatment of colonic obstruction; other uses are described in detail elsewhere. 4 , 6

Cecal perforation is an absolute contraindication for percutaneous cecostomy. Relative contraindications are similar to those for percutaneous catheter insertion, including coagulopathy and prolonged dilatation of the cecum that may cause ischemia of the cecal wall. In such cases, careful evaluation of the acute abdomen is necessary, as emergent surgical exploration may be required.

27.2.2 Procedure

Patient Evaluation and Preparation

Patient evaluation includes an assessment of the patient′s general condition and comorbidities. Routine hematologic, metabolic, and coagulation panels should be obtained. Additional cardiovascular or respiratory evaluation may be necessary for frail patients with a history of acute or chronic cardiorespiratory insufficiency. Usually, these patients have undergone plain radiography or computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen for imaging evaluation of their disease and for treatment planning.

Patient preparation for percutaneous cecostomy is usually minimal. Patients with colonic obstruction should be fasting and should have a nasogastric tube in place. Oral or rectal bowel preparations are not necessary; however, when percutaneous cecostomy is used for chronic constipation or fecal incontinence, various bowel regimens are advocated.

Procedural sedation or monitored anesthesia care is sufficient for patients undergoing percutaneous cecostomy. Intravenous conscious sedation (midazolam and fentanyl) and local anesthesia (lidocaine 1%) are the authors’ preferences.

Image Guidance

C-arm fluoroscopy can clearly identify the location of the cecum and is reliably accurate for percutaneous cecostomy performance. Some colleagues have used CT for percutaneous cecostomy guidance. Ultrasound can be useful in preventing injury to the epigastric vessels and may be needed to identify a fluid-filled cecum and to guide bowel puncture.

Materials Needed

General tray.

Percutaneous sutures (Saf-T-Pexy T-fasteners [Kimberly-Clark] or Brown-Mueller T-fasteners).

Access needle: Seldinger thin-wall 19 gauge.

Guidewires: Amplatz 0.038-inch, 4- to 7-cm floppy tip.

Dilators: 7 to 14 French (Fr) or coaxial dilator (Kimberly-Clark).

Catheters: Multipurpose locking pigtail catheter 10.2- to 14-Fr suffices for gas and liquid stools decompression. Catheters with larger diameters may be needed for cecostomy colonic decompression if catheters with smaller diameters are unable to decompress the dilated cecum (▶ Fig. 27.4)

Drainage bag connected to the catheter for evacuation of gas and liquid stools. An ostomy bag leaving the catheter inside may be necessary for evacuation of enteric content with particles or liquid stools

Technique

Identification of the cecum: The previous imaging studies are reviewed to confirm that the dilated cecum is against the abdominal wall with the bowel not intervening. An abdominal fluoroscopic survey is used to identify the cecum and its most accessible portion for cecopexy and percutaneous cecostomy catheter insertion. Supplemental ultrasound is used to identify the location of the epigastric vessels and to guide puncture of a fluid-filled cecum. CT guidance may be necessary if the cecum′s position does not seem consistent with its position on the preprocedural CT scan.

Cecopexy and percutaneous cecostomy access: Under image guidance, the anterior wall of the cecum is fixed to the anterior abdominal wall with three percutaneous sutures. Once the cecum is anchored to the abdominal wall, the lumen of the cecum is accessed in the center of the cecopexy using the Seldinger needle. The guidewire is then inserted and directed distally in the ascending colon. The enterocutaneous tract is dilated by serial dilatation or by the use of a coaxial dilator to the diameter of the catheter to be inserted. The cecostomy catheter is placed approximately 10 to 15 cm into the cecum and ascending colon over the guidewire. Aspiration through the catheter is performed to determine whether evacuation of the cecum is effective. If evaluation is not effective, a larger diameter catheter may need to be inserted. Once evacuation is achieved, the catheter is secured in place to the skin with two sutures. Some authors advocate placing the catheter tip within the luminal gas rather than within fecal material. An ostomy appliance is placed over the catheter or a drainage bag is connected to the proximal catheter.

27.2.3 Postprocedural Care

After percutaneous cecostomy, the patient should be followed up to assess for effective decompression, catheter status, and the presence of complications. As soon as the patient is eliminating gas and liquid stools through the cecostomy, the nasogastric tube should be removed and oral intake of fluids should be resumed. Nutrition by mouth should be advanced to tolerance and according to the ultimate management of the colonic obstruction. Patients who are able to have their obstruction corrected with surgery will be prepared for the procedure. Those patients who cannot have their obstruction resolved may have the cecostomy for life.

On a long-term basis, fecal material may clog the catheter, requiring flushing with normal saline. Exchanges are needed when the catheter has hardened because of stool residue, dislodgement, migration, dysfunction, or occlusion.

27.2.4 Complications

Major complications of percutaneous cecostomy include peritonitis and abdominal wall infection. The latter occurred in 1 patient of 27 (3.7%) in one series 1 ; a pericecal abscess occurred in 1 patient of 23 (5%) in another series. 7 Minor complications include leakage around the tube, transient pain, and catheter dislodgement. 1 , 7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree