Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

DEFINITION

Focal dilation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta of at least 150% of the normal diameter (range 1.4 to 3.0 cm, average 2.0 cm) is the usual definition of an aneurysm. 18 Therefore aortic dilation above 3 cm indicates a possible aneurysm. Some sources state that 4.0 cm is clearly diagnostic. 18,10 Consultation with an experienced surgeon is indicated when it reaches a diameter of 5.0 cm (some say 5.5 cm).

INCIDENCE

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) affects approximately 2% to 8% of the population over 60 years of age. 18 Incidence increases rapidly in men after age 55 and in women after age 70. Overall incidence and deaths resulting from AAA are more common in men. 6,14 In one screening study of nearly 30,000 65-year-old men, the prevalence of AAA (confirmed by at least two ultrasound studies) was 5% and 80% of AAAs detected were smaller than 4.0 cm. 11

RUPTURE (RATES AND MORTALITY)

Each year in the United States more than 15,000 deaths, many of which are preventable, are attributed to abdominal aortic aneurysm. 4 Natural history of most aneurysms is one of gradual enlargement; growth rates have been estimated to average 0.2 cm/year for aneurysms under 4 cm and 0.5 cm/year for those over 6 cm. 18 Although impossible to predict for a given individual, the risk of AAA rupture increases with larger initial aneurysm diameter, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Expansion rates of AAAs for men 65 years of age are listed in Table 31-1. 11 Rupture of AAA is considered essentially inevitable if the patient lives long enough. 14 Once rupture occurs, massive intraabdominal bleeding usually occurs and usually is fatal, with a mortality rate of 80% to 90%, unless prompt surgery can be performed. 4,18 A relatively low risk of rupture is seen for asymptomatic, slow-growing AAA under 6 cm. Table 31-2 lists the estimated annual rates of rupture related to AAA. 9,18

| Initial size measured on ultrasound | Expansion rate per year |

|---|---|

| 2.6–2.9 cm | 0.09 cm |

| 3.0–3.4 cm | 0.16 cm |

| 3.5–3.9 cm | 0.32 cm |

| Size of abdominal aortic aneurysm | Annual rate of rupture |

|---|---|

| 4.0–4.9 cm | 1% |

| 5.0–5.9 cm | 3% |

| 6.0–6.9 cm | 9% |

| ≥7.0 cm | 25% |

RISK FACTORS

The underlying cause of AAA is multifactorial, including such factors as smoking, hypertension, and processes that result in an inflammation that may lead to dilatation and subsequent plaque deposition. 7 Other uncommon possible causes include infection, inflammatory disease, increased protease activity within the arterial wall, genetically regulated defects in collagen and fibrillin, and mechanical factors. 7 An individual’s risk is increased twelve-fold if a first-degree relative has an AAA. 6 In addition to family history of aneurysms, increasing age and male gender are established risk factors. Understanding the established as well as possible risk factors assists the clinician in determining an index of suspicion for the presence of AAA (Table 31-3). AAA is best repaired as an elective, not emergency, procedure.

| Established risk factors | Comments |

|---|---|

| Increasing age | Most studies focus on ages 65–80 |

| Male gender | More frequent and at an earlier age than in females. The male to female ratio for death from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is 11:1 between ages 60 and 64 and narrows to 3:1 between 85 and 90 |

| Family history of aneurysm | Increases individual’s risk twice, especially first-degree male relative |

| Possible risk factors | Comments |

| Tobacco use | Long-term smoking increases individual’s risk five times over the baseline |

| Systemic atherosclerosis disease | Including peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, history of coronary artery bypass, history of myocardial infarct have modest correlation; less association with smaller AAA than with larger AAAs |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Difficult to establish as an independent risk factor |

| Hypertension | Weak correlation |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Weak correlation, specifically related to hypertriglyceridemia |

| Caucasian race | AAAs are uncommon in African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics |

IMAGING FINDINGS

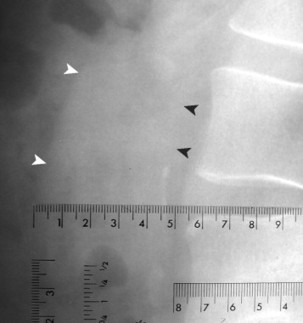

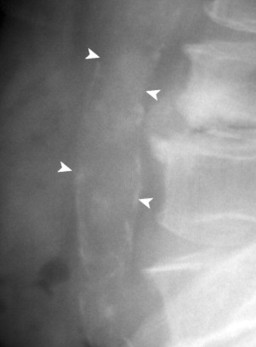

Ultrasonography (US) reaches almost 100% accuracy18 in detecting AAA, making it ideal for screening, diagnosis, and follow-up studies in suspected cases. 3 Obesity and excessive bowel gas may interfere with US imaging. 14 Approximately 50% of AAAs may be seen as cystlike calcifications on plain film radiography resulting from the calcium content of atherosclerotic plaques (FIG. 31-1FIG. 31-2FIG. 31-3FIG. 31-4FIG. 31-5FIG. 31-6FIG. 31-7FIG. 31-8 and FIG. 31-9). 14

|

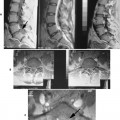

| FIG. 31-1 Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lateral view demonstrates a calcified wall of a fusiform abdominal aorta (arrows). Plain film visualization is possible because of the calcium content of atherosclerotic plaques. Most abdominal aortic aneurysms occur between the renal artery and iliac bifurcation. |

|

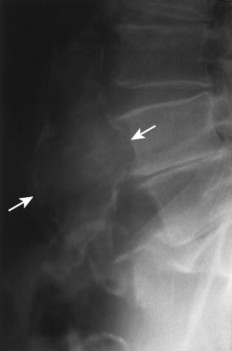

| FIG. 31-2 Abdominal aortic aneurysm presenting in an anteroposterior lumbar projection. Note the characteristic thin rim of curvilinear calcification (arrows). The location to the right of the spine indicates an extremely large aneurysm. (Courtesy Cynthia Peterson, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.) |

|

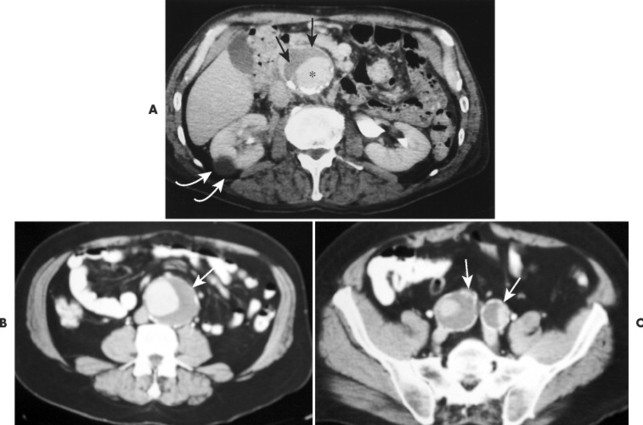

| FIG. 31-3 A, Abdominal aortic aneurysm: computed tomography with intravenous contrast. This scan shows a large, partially calcified abdominal aortic aneurysm anterior to the spine. Within the aneurysm is a region of increased density (asterisk) that corresponds to the functional lumen of the aneurysm; the remaining low-attenuated region represents a large thrombus (arrows). Note the renal cyst (curved arrows). B and C, Same imaging methods applied to a different patient reveal abdominal aortic and iliac aneurysms (arrows). (B and C, Courtesy Julie-Marthe Grenier, Davenport, IA.) |

|

| FIG. 31-4 Abdominal aortic aneurysm measuring 4.7 cm on the lateral 40-inch focal film distance lateral lumbar projection. Any measure larger than 3.0 cm is suspicious of aneurysm, and values over 4.0 cm warrant further investigation with ultrasound. In this case, the ultrasound examination validated the presence of aneurysm. Note the faint linear radiodensity of the anteroposterior margin of the vessel (arrowheads). Interpreters are cautioned not to assume that wall calcification is requisite to aneurysm formation. Any suggestive linear shadows, as seen in this case, warrant consideration for an ultrasound examination. |

|

| FIG. 31-5 Aorta is calcified, but not enlarged (arrowheads). No evidence of aneurysm is present in this case. The sole finding of vascular wall calcification of the abdominal aorta does not warrant further investigation. |

|

| FIG. 31-6 A and B, Two cases of an expanded aorta (arrowheads) consistent with aneurysm. |

|

| FIG. 31-7 A 12.5-cm aneurysm seen in prominently in, A, the anteroposterior projection and, B, only faintly in the lateral projection (arrowheads). (Courtesy Robert C. Tatum, Davenport, IA.) |

|

| FIG. 31-8 A 74-year-old man exhibiting prominent calcification of the anterior and posterior walls of the abdominal aorta. A focal dilation of 4.7 cm is noted (arrowheads), consistent with aneurysm. In addition to the overall size of the vessel, aneurysms often exhibit a focal bulge, disrupting the parallel continuity of the walls of the vessel. For instance, the focal nature of the budge seen in this case would represent a concern for aneurysm, regardless of its size. |

|

| FIG. 31-9 A and B, Aneurysm of the abdominal aorta presenting in an 87-year-old man. Largest visible diameter of the vessel measures 5.8 cm (arrowheads). |

Computed tomography (CT) provides better anatomic detail, especially regarding the aneurysm’s relationship to the renal arteries, which is very important information for surgical planning (see Fig. 31-3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates excellent anatomic detail and sizing of aneurysms but provides no distinct advantage and is more expensive than CT. Aortography often is ordered for surgical planning, although it is not appropriate for diagnosis. 14 It may significantly underestimate the width of the aneurysm because large areas of thrombus can fill an aneurysm and aortography shows only the residual central canal (which can resemble a normal-sized aorta).

Diagnosis is made by US for the majority of patients, and preoperative planning is based on aortography. US (which is faster and less expensive than other methods) and CT are ways to follow up nonsurgical cases in which the diameter is less than 5 cm, although some surgeons feel this is too large a dividing point. 14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree