Diagnosis: Dural venous sinus thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarctions

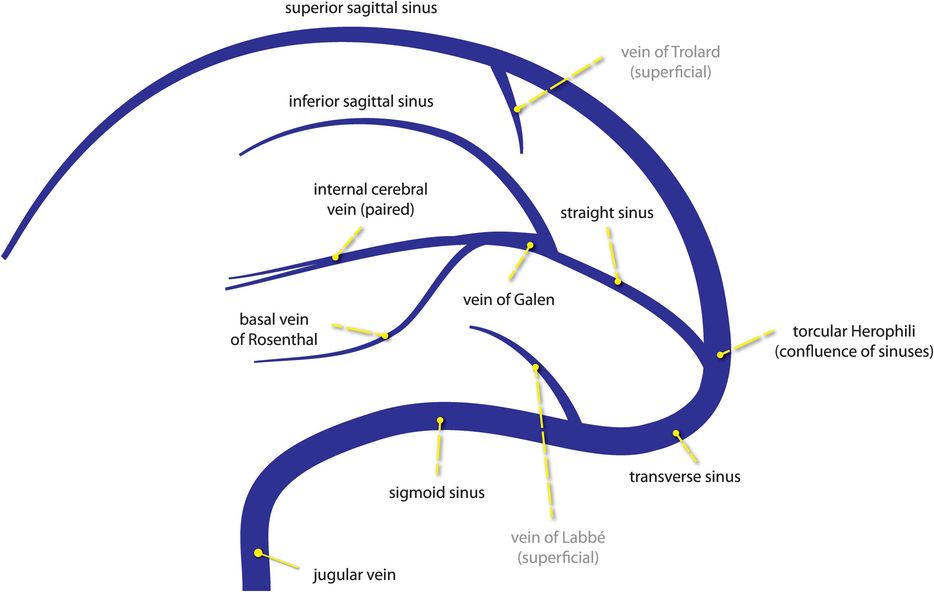

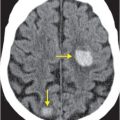

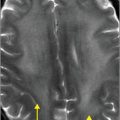

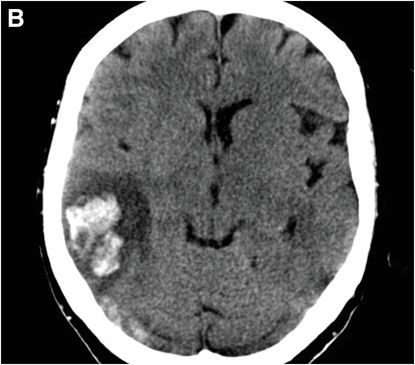

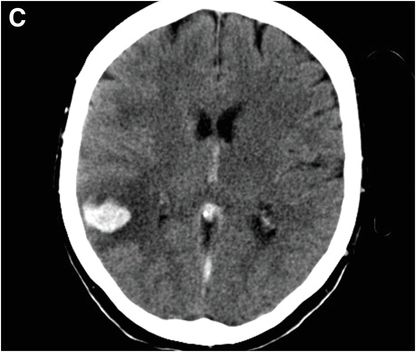

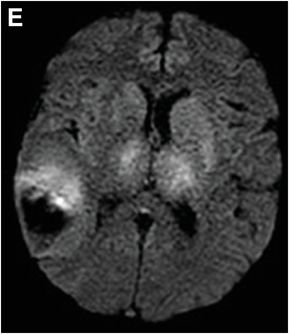

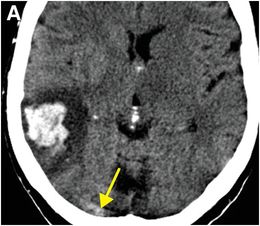

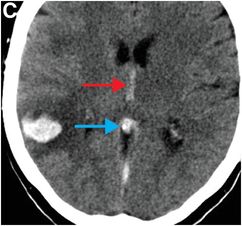

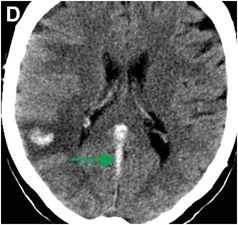

Axial unenhanced CT images (A, C, D; image B is not shown in these annotated images) show a right posterior temporal hemorrhage and left larger than right thalamic and left basal ganglia venous infarcts (seen as subtle asymmetrical hypoattenuation) due to thrombosis (high attenuation) of the right transverse sinus (yellow arrow, A); internal cerebral veins (red arrow, C), vein of Galen (blue arrow, C) and straight sinus (green arrow, D).

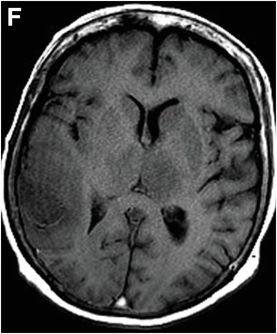

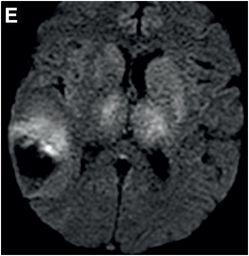

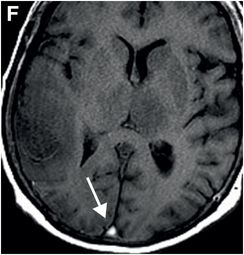

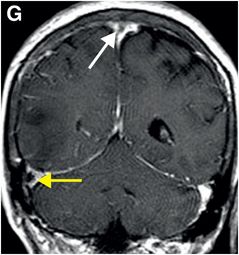

MR images (E–G) demonstrate similar findings: DWI (E) shows signal abnormality in the left greater than right thalamus, basal ganglia, and posterior right temporal lobe consistent with infarction. The right temporal lobe infarct is hemorrhagic. Thrombus in the superior sagittal sinus is hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging (white arrow, F). Post-contrast T1-weighted image (G) shows filling defects within the superior sagittal (white arrow) and right transverse (yellow arrow) sinuses.

Discussion

Overview and risk factors for intracranial venous thrombosis

Intracranial venous thrombosis is thrombosis of cortical veins or deep venous sinuses and is one of the more common causes of stroke in young patients.

Intracranial venous thrombosis more commonly affects females, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:1. Women in their thirties are often affected due to usage of oral contraceptive pills and pregnancy, as both conditions promote a hypercoagulable state.

Neonates who have undergone complicated deliveries are also at relatively increased risk for venous thrombosis due to dehydration and shock. The incidence of peripartum and postpartum venous sinus thrombosis is approximately 12 cases per 100,000 deliveries.

Other predisposing conditions include thrombophilias, head and neck infections including sinusitis, trauma, neoplasms, medical instrumentation, renal insufficiency, and inflammatory diseases such as Behçet’s.

Clinical presentation of intracranial venous thrombosis

Intracranial venous thrombosis is an uncommon, at times diagnostically challenging, condition that presents with nonspecific symptoms.

Patients with intracranial venous thrombosis most commonly present with headaches (in more than 90% of cases). Headaches tend to progress slowly, from mild to severe, differentiating them from the “worst headache of life” typical of subarachnoid hemorrhage from aneurysm rupture.

Other presenting symptoms include visual changes (with the clinical exam finding of papilledema from increased intracranial pressure), stroke-like syndrome, and seizures. In the elderly, symptoms can be even less specific (e.g., mental status change).

Physiology of intracranial venous thrombosis

The pathophysiology of venous infarct differs from that of arterial infarct. Occlusion of the major intracranial venous sinuses results in venous congestion, impaired CSF absorption, and ultimately, increased intracranial pressure.

Elevated intracranial pressure may sometimes be the only sequela of venous sinus thrombosis. In the setting of robust collateral drainage (pre-existing or developed in response to venous thrombosis) or recanalization of the thrombosed vein, parenchymal damage may be absent or completely reversible. If venous pressure exceeds arterial perfusion pressure, infarction and hemorrhage may occur.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is an uncommon condition due to retrograde extension of sinonasal or orbital infection, although the incidence of this condition has decreased since the advent of antibiotics. Immunocompromised patients are at higher risk. The typical presentation is sinusitis with cranial neuropathy that progresses from unilateral to bilateral over a relatively short period of time.

Imaging of intracranial venous thrombosis

The appearance of venous sinus thrombus on unenhanced CT is variable depending on the age of the clot and the patient’s hydration status. Noncontrast CT may show high-attenuation thrombus within a superficial or deep venous sinus (often, the superior sagittal sinus), with or without associated venous infarction that may or may not have hemorrhaged.

In cortical vein thrombosis, linear, irregular, high-attenuation material within the vein is known as the “cord” sign. The triangular hyperdensity associated with superior sagittal sinus thrombosis is referred to as the “delta” sign.

Venous sinus thrombosis should always be considered in the setting of a peripheral hemorrhage or infarct that does not correspond to a typical arterial distribution.

Deep system thrombosis (involving the paired internal cerebral veins, vein of Galen, or straight sinus) should be included in the differential diagnosis of bilateral thalamic infarction in addition to occlusion of the artery of Percheron.

In comparison to unenhanced CT, contrast CT venography (CTV) is superior for delineation of the site and extent of sinus thrombosis. If thrombus is present within the superior sagittal sinus, axial images will demonstrate a central filling defect outlined by a rim of enhancement (the “empty delta” sign).

There are several potential challenges in interpreting CTV. Venous sinus filling defects from normal arachnoid granulations may create false positives. Conversely, hyperdense clot may simulate a patent sinus, resulting in a false negative study. Thus, it is imperative to compare CTV images with noncontrast CT images. Appropriate timing of the contrast bolus (ideally a 45–50-second delay) is also an important technical consideration.

On MR imaging, thrombus demonstrates increased signal on T1-weighted images and loss of normal flow void on T2-weighted sequences and time-of flight MR venogram (MRV).

False positives on MRV can be caused by slow flow. In addition, T1 shine-through from methemoglobin-containing thrombus may mimic flow, leading to false negatives. Comparison between contrast-enhanced and noncontrast T1-weighted images is therefore useful in resolving these potential pitfalls.

The signal characteristics of thrombus vary over time. Subacute thrombus exhibits high signal intensity on T1-weighted images, while acute and chronic clots tend to be isointense to venous blood. Arachnoid granulations present as filling defects within the dural venous sinuses, though often assume a more discrete lobulated round appearance as compared to thrombus.

Gradient echo images are useful to detect susceptibility “blooming” effect associated with paramagnetic components within blood products.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree