5 Aneurysms

Introduction

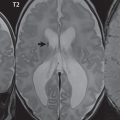

By definition, an aneurysm is an abnormal dilatation, typically saccular or fusiform in shape, of an artery. Intracranial aneurysms are thought to result from hemodynamic stress, abnormal remodeling, and inflammation. Saccular aneurysms are generally found at arterial branch points, although many are not clearly associated with branch vessels. Multiple lobes and daughter sacs (“Murphy’s tit”) are common in ruptured aneurysms. Rupture is typically at the apex. Although variable percentages in terms of sites of occurrence are published in the scientific literature, for unruptured aneurysms without subarachnoid hemorrhage, MCA, cavernous carotid ( Fig. 5.1 ), and distal internal carotid are the most common (about 20% each), followed by PCOM and ACOM (including ACA) aneurysms (about 10% each). Posterior circulation aneurysms are least common, with about 5% vertebrobasilar/PCA and 5% basilar tip. The prevalence of aneurysms in the general population, without subarachnoid hemorrhage, is about 3%. The prevalence is higher in patients with atherosclerosis and also increases with age.

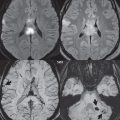

Multiple aneurysms are found in about 20% of all aneurysm cases ( Fig. 5.2 ). Risk factors for multiple aneurysms include smoking and hypertension (which are felt to be risk factors as well for development of a single, isolated aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage). Infundibula, conical dilatations at an artery origin, are benign incidental findings not to be confused with an aneurysm. Intracranially, an infundibulum is most common at the PCOM origin.

There are several medical conditions well known to be associated with aneurysms. The two most important are polycystic kidney disease and a familial disposition. Estimates of prevalence of intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) range widely (up to 40%). The risk of aneurysm rupture with subarachnoid hemorrhage appears to be higher than in the general population, with presentation at a younger age. Twenty-five percent of patients with ADPKD and an aneurysm develop a second aneurysm within 15 years. Screening by noninvasive imaging is reasonable in ADPKD patients with a known aneurysm or prior subarachnoid hemorrhage or in patients who have a familial history.

In considering familial aneurysms, specifically when at least two first-degree relatives are affected, assessments of prevalence range widely, with 10% likely a reasonable estimate. There is a predilection for the middle cerebral artery, as well as for multiple aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage at a younger age. Screening of such patients, if pursued, should be by noninvasive imaging. Other less common conditions with an increased incidence of intracranial aneurysms include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, fibromuscular dysplasia, and in association with an arteriovenous malformation.

The natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms is controversial. The overall risk of rupture is likely 1 to 2% per year. The rate of rupture appears to be lower for small anterior circulation aneurysms. Larger aneurysms are at greater risk for rupture. However, if an aneurysm ruptures (with subarachnoid hemorrhage), the mortality rate is very high, greater than 50%.

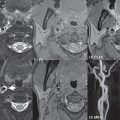

Although a small saccular aneurysm may be visualized on a conventional MR or CT scan, 3D time of flight (TOF) MR angiography (MRA) and CT angiography (CTA) are specifically employed for detection and delineation ( Fig. 5.3 ). CTA is the modality of choice in the acute presentation with subarachnoid hemorrhage, while 3D TOF MRA is often used for detection and evaluation of asymptomatic aneurysms, as well as for correlation and further definition of lesions in the acute setting and on followup. Modern scanners easily detect aneurysms as small as 2 mm in diameter. Treatment of intracranial brain aneurysms that have bled, or are deemed to present a significant risk to the patient because of potential bleeding in the future, is by either surgical clipping or endovascular occlusion. Surgery is much less common today, although not all aneurysms can be treated by an endovascular approach.

Aneurysm Treatment

Asymptomatic patients with untreated intradural aneurysms are followed in some centers by annual CTA or MRA. Growth or new symptoms, such as headaches or cranial nerve palsies, raise concern in regard to impending rupture. Cessation of smoking and appropriate management of hypertension are felt to be important. Treatment of unruptured aneurysms, if desired or indicated, is currently performed either by surgery or by endovascular means.

Surgical

Surgical treatment was considered in the past to be the gold standard for treatment ( Fig. 5.4 ); however, complication rates are high. In surgical treatment of unruptured aneurysms, the mortality rate is about 3%, with permanent morbidity seen in up to 20%. Risk factors for surgery in this group of patients include age, size of the aneurysm (> 12 mm), and location in the posterior circulation. In surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms, the mortality rate is about 15%, with substantial, permanent morbidity in an additional 15%.

In surgical series, the frequency of a residual aneurysm is 4 to 8%. Catheter angiography, which can be performed intraoperatively, is necessary to confirm complete occlusion of the aneurysm and preservation of associated vessels. There is an increased rate of rupture after clipping when a portion of the aneurysm remains, and enlargement of the residual portion of an aneurysm following clipping has been documented. Recurrence has also been shown in 1% of aneurysms after complete surgical obliteration, the latter confirmed by postoperative angiography ( Fig. 5.5 ).

Endovascular

The complication rate with endovascular treatment of an unruptured brain aneurysm is approximately 10% ( Fig. 5.6 ). The rate of permanent complications is less than half this figure. Repeat hemorrhage is uncommon, seen in 3%.

The advent of detachable coils, led by the development of the Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) conceived serendipitously in the early 1980s, enabled development of the field of aneurysm coiling as we know it today. With this system, until the coil is in satisfactory position, it remains attached to the pusher wire. Detachment is achieved by application of a low-amplitude electrical current, causing electrolysis of the connection between the coil and the wire. Numerous technical refinements have followed, with an array of shapes and sizes available. Augmented (bioactive) coils continue to attract interest, with the goal to promote thrombosis and fibrosis, thus reducing the likelihood of subsequent recanalization. Wide-neck aneurysms present an additional challenge, with one current approach being deployment of a thin wire mesh stent across the neck, within the parent vessel. Coils are then placed via a microcatheter that enters the aneurysm through the interstices of the stent, with the latter acting as a scaffold to hold the coils within the aneurysm. The relatively recent advent of flow-diverting stents, for example, the Pipeline Embolization device, may lead to a further paradigm shift in endovascular aneurysm treatment.

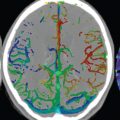

Complete occlusion of an aneurysm following coiling is reported in about 50%, with “near complete” in 90%. Recurrence after coiling (defined as recanalization sufficiently large to allow retreatment, either surgical or endovascular) is seen in about 20% of patients 1 to 2 years following initial treatment ( Fig. 5.7 ). Larger aneurysms (> 10 mm) and those with a wide neck are more prone to recurrence. Recurrences are also more common following suboptimal initial endovascular treatment. In terms of the relationship to the parent vessel, terminal aneurysms tend to recur more frequently than sidewall aneurysms. Due predominantly to the risk of recurrence, longterm followup/surveillance with MR or DSA is recommended ( Fig. 5.8 ).

Comparison of Surgery and Endovascular Treatment

Significantly lower rates of morbidity and mortality are found with coiling of unruptured intracranial aneurysms when compared to clipping. Decreased length of stay, hospital charges, and periprocedural complications also significantly favor coiling of unruptured aneurysms. With ruptured aneurysms, several studies have shown little difference between surgical and endovascular treatment, other than the greater recurrence rate following the latter. Other studies, and specifically the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT), have shown decreased mortality and significant morbidity in the endovascular group, together with a significantly reduced risk of vasospasm and ischemic neurologic deficits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree