5 Skull Base and Temporal Bone(Table 5.5 – Table 5.7)

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Labyrinthine aplasia (Michel deformity) | Petrous bone lacks cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals; amorphous bone instead of inner ear structures. Associated abnormalities: small or absent internal auditory canal, hypoplastic or absent petrous apex, flattened medial wall of middle ear (because neither the promontory nor the lateral semicircular canal bulges into the tympanic cavity), ossicle absence or fusion. Geniculate ganglion is posterior to normal location. Facial nerve bony canal is prominent. | Extremely rare congenital inner ear malformation characterized by complete lack of development of the inner ear. The developmental arrest occurs at the third gestational week. May be unilateral or bilateral. Seen in Klippel-Feil syndrome and thalidomide exposure. Sensorineural hearing loss from birth. |

Cochlear aplasia | Complete absence of cochlea. Vestibule, semicircular canals, and internal auditory canal are variably affected: normal, hypoplastic, or dilated. Cochlear promontory is flat. Labyrinthine, geniculate ganglion, and anterior tympanic portions of facial nerve course occupy site where cochlea should be. External auditory canal, middle ear, ossicular chain, bony vestibular aqueduct, and endolymphatic duct are of normal size. Cochlear hypoplasia: The cochlea consists of a small 1- to 3-mm bud. The vestibule may be enlarged, and semicircular canals may be normal or deformed. | Extremely rare inner ear anomaly, usually bilateral. The developmental arrest occurs at the late third gestational week. Sensorineural hearing loss from birth. |

Mondini malformation | The cochlea is small and consists of a normal base turn and a single ovoid cavity instead of the middle and apical turns with modiolar deficiency and interscalar septum absence. In the pseudo-Mondini malformation, the basal turn is enlarged too. Mondini malformation is associated in 20% of cases with anomalies of the vestibule, semicircular canals, and endolymphatic duct/sac. | Malformation of the bony inner ear with loss of the normal two and one half turns to the cochlea. May be unilateral or bilateral. Mondini malformation has been reported in campomelic dysplasia, CHARGE association, congenital CMV infection, hemifacial microsomia, trisomy 21, branchio-otorenal syndrome, Johanson-Blizzard syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome, Pendred syndrome, and Pierre Robin syndrome. Clinically the hearing loss is total. Because of an associated perilymph fistula, recurrent meningitis or recurrent CSF otorrhea that mimics otitis media with effusion may occur. |

Cystic common cavity | Cochlea and vestibule are fused and seen as a common, featureless cavity without differentiation and of variable size (averaging 7–10 mm in diameter). The semicircular canals may be normal, deformed, or absent. Internal auditory canal, entering the anterior aspect of the common cavity, may be normal, small, or large. External auditory canal, middle ear structures, mastoid, and vestibular aqueduct are normal. | Rare congenital inner ear malformation, unilateral or bilateral, with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Arrest of development occurs at the fourth gestational week. |

Cystic cochleovestibular anomaly | “Snowman”-shaped bony inner ear with confluent cystic cochlea and vestibule with no internal structures visible. Semicircular canals are present but with variable shape and degree of dilation. The internal auditory canal may be dilated with defective fundus. External auditory canal, middle ear structures, mastoid, and vestibular aqueduct are normal. | Rare inner ear anomaly with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Arrest of development occurs at the fifth gestational week. Sensorineural hearing loss from birth. |

Semicircular canal dysplasia | Sporadic semicircular canal dysplasia: Dilated lateral semicircular canal forming single cavity with dilated vestibule. Posterior and superior semicircular canal may be normal, dilated, or hypoplastic. Cochlea can be normal or with incomplete apical and middle turn partition. Oval window atresia is commonly associated. Syndromic semicircular canal dysplasia: All semicircular canals are absent in both ears, the vestibule is small and dysmorphic, oval window atresia is always present, and cochlear anomalies (most common “isolated” cochlea with lack of cochlear aperture) are usually associated. Semicircular canal dysplasia or aplasia may be associated with labyrinthine aplasia, cochlear hypoplasia, or cystic common cavity deformity. | Rare inner ear anomaly with malformation, hypoplasia, or aplasia of one or all of semicircular canals. Arrest of development occurs at the sixth to eighth gestational week. May be part of genetic syndromes (CHARGE, Alagille, Kallmann, Noonan, Waardenburg, Crouzon, and Apert). Sensorineural hearing loss from birth. Conductive hearing loss often is present due to oval window atresia and ossicular chain anomalies. |

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence | Uni- or bilateral small and complete defect in the bony wall of the one- to three-layer roof of the superior semi-circular canal. Extreme thinning of tegmen tympani may be associated. | Treatable form of vestibular disturbance, most likely a developmental anomaly. Dehiscence of bone overlying the superior semicircular canal can result in a syndrome of slowly progressive dizziness and/or oscillopsia evoked by loud noises or by maneuvers that change middle ear or intracranial pressure, disabling disequilibrium, Tullio phenomenon (vertigo and/or nystagmus related to sound), conductive hearing loss in spite of normal middle ear function, and vertical-torsional eye movements in the plane of the superior semicircular canal evoked by sound and/or pressure stimuli. Mean age: 42 y (range 20–70 y). |

Large vestibular aqueduct syndrome | Describes the bony anomaly seen on temporal bone CT: V-shaped enlarged bony vestibular aqueduct with a midbony vestibular aqueduct diameter > than 1.5 mm, wider than the posterior semicircular canal diameter; 16% to 26% of ears with large vestibular aqueduct have a Mondini or pseudo-Mondini malformation. Associated vestibular (i.e., enlargement of the utricle area) and/or semicircular canal anomalies may be obvious. Complementary T2-weighted MRI can easily identify a corresponding enlarged endolymphatic duct and sac in foveal area and an associated cochlear dysplasia (CT does not give any information about the endolymphatic sac). | Most common congenital anomaly of the inner ear found by imaging. Arrested development of inner ear at seventh gestational week leaves large endolymphatic duct and sac associated with cochlear dysplasia. Bilateral anomaly in 90%. Most cases are sporadic, but it has been reported in brachio-otorenal syndrome, CHARGE association, congenital CMV infection, and Pendred syndrome. Sensorineural hearing loss develops with variable speed and may not be present until early adult life. |

Internal auditory canal stenosis or atresia | The normal canal’s vertical diameter varies from 2 to 12 mm (mean 5 mm) and its length from 4 to 15 mm (mean 8 mm). In 95% of normal individuals, the difference between the two internal auditory canals does not exceed 1 mm in diameter and 2 mm in length. A narrow internal auditory canal (IAC) can be diagnosed when the diameter of IAC is < 2 mm, and any acquired osseous condition predisposing to stenosis of the IAC is absent. A narrow internal auditory canal with duplication divided by bony septation is extremely rare. CT has a limited role in assessing the neural components of the internal auditory canal (MRI should be performed to look for the defect of neural structures in the IAC of patients with sensorineural hearing loss). | IAC anomalies, including atresia, stenosis, aplasia, and hypoplasia, are all rare congenital malformations of the temporal bone with or without congenital sensorineural hearing loss. It is theorized that this anomaly of the IAC results from altered cochleovestibular nerve development secondary to faulty chemotactic mechanisms or a lack of end-organ targets. Unilateral IAC anomalies are often seen in conjunction with other inner ear anomalies and occasionally with middle or external ear anomalies. Infrequently, it will occur as either an isolated or bilateral finding, associated with other systemic developmental anomalies, such as cardiac septal defects, polycystic kidney disease, skeletal deformities, and duodenal atresia. Acquired stenosis of the canal is caused by fibrous dysplasia, Paget disease, osteopetrosis, other more unusual bony dysplasias, osteomas, and meningiomas. |

Epidermoid | Homogeneously hypodense, irregular, or lobulated nonenhancing cerebellopontine angle mass. | Epidermoid cyst usually occurs in the cerebellopontine cistern (4%–5% of cerebellopontine angle mass lesions), but is rarely seen within the internal auditory canal. Typical age: 20 to 50 y. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Labyrinthine ossification | Diffuse or localized membranous labyrinthine fluid space ossification. Unilateral if tympanogenic, bilateral if meningogenic, or hematogenic. Cochlear labyrinthine ossificans: Fluid spaces of the cochlea itself are affected. Noncochlear labyrinthine ossificans: Fluid spaces of the semicircular canals or vestibule are affected. MRI can already show fibrous obliteration of membranous labyrinth in prelabyrinthine ossificans phase with labyrinthitis, whereas CT cannot. | Membranous labyrinth ossification is a healing response to infectious, inflammatory, traumatic, or surgical (i.e., previous labyrinthectomy) insult to inner ear. Labyrinthitis progresses to labyrinthine ossificans when suppurative. Infection may be tympanogenic (secondary to chronic otitis media or cholesteatoma), meningogenic (secondary to meningitis, usually bacterial in origin), or hematogenic (secondary to blood-borne infection, most often viral in origin, e.g., measles and mumps). Meningogenic labyrinthitis is the most common cause of acquired bilateral childhood deafness. Severe vertigo is an infrequent but devastating symptom. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Vestibulocochlear schwannoma | Well-delineated, enhancing mass centered near the porus acusticus with an elongated intracanalicular component and bulbous cisternal component in the cerebellopontine angle that result in an “ice cream cone” configuration. Pressure of the growing tumor results in erosion of the walls and consequent enlargement of the internal auditory canal. May bow the crista falciformis cephalad and flare the internal auricular canal when large. Usually solid but may show cystic or hemorrhagic change, particularly in large or rapidly growing tumors. Calcification is not present. Small ovoid lesions may be contained entirely within the internal acoustic meatus and may be missed with CT. (MRI is the preferred imaging modality for detecting and describing vestibulocochlear schwannomas. CT pneumocisternography is obsolete.) | Vestibulocochlear schwannoma is a common benign, slow-growing neoplasm that arises from Schwann cells of the vestibulocochlear nerve sheath (in particular at the glial-Schwann cell junction of the vestibular nerve), accounting for three fourths of all cerebellopontine angle masses and one tenth of all intracranial tumors. Schwannomas can affect other cranial nerves but have a predilection for the eighth nerve. Patients usually present in the fourth to six decades with slowly progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus, cerebellar dysfunction, or neuropathy of the lower cranial nerves. Vestibular symptoms (vertigo, dizziness) are less common. Bilateral vestibulocochlear schwannomas are the hallmark lesion of neurofibromatosis type 2, in a child or young adult. Other lesions found in NF2 are dural ectasia with no tumor mass within the dysplastic canal; meningiomas, sarcomas, and schwannomas of other cranial nerves; ependymomas; gliomas; and juvenile posterior subcapsular cataract. |

Meningioma | Meningiomas limited to the internal auditory canal are rare and mimic a vestibulocochlear schwannoma both clinically and by imaging. | Meningiomas are the second most common tumor of the cerebellopontine angle and usually arise outside the internal auditory canal on the posterior surface of the petrous bone, although they may extend within the medial portion of the canal. They grow either as a solid mass with broad dural base and obtuse angle with the temporal bone or en plaque and may cause hyperostosis or erosion of the adjacent bony structures. Calcifications may occur. |

Facial nerve schwannoma | Facial schwannomas may occur within the internal auditory canal but are usually recognizable because of the extension into the facial nerve canal as tubular or ovoid-shaped enhancing masses following the course of the intratemporal facial nerve with a smooth enlargement of the facial nerve canal and benign, sharply marginated remodeling of the geniculate fossa. A large tumor may extend into the middle ear cavity and protrude into the posterior cranial fossa. | Rare benign tumors of the Schwann cells that invest the peripheral facial nerve. Usually involve the geniculate ganglion but may involve any portion of the facial nerve (intratemporal > cerebellopontine angle/internal acoustic canal > intraparotid). Patients present with facial nerve dysfunction or hearing loss. |

Lipoma | Fat-density, nonenhancing lesion, usually located at the fundus of the internal auditory canal. | Lipomas are rare internal auditory canal lesions. They may also involve the cerebellopontine angle region and the labyrinth. |

Facial nerve hemangioma | Poorly marginated enhancing soft tissue mass of the petrous pyramid, extending into the fundus of the internal auditory canal with distinctive amorphous “honeycomb” bone changes. Otic capsule is spared. | Rare intratemporal benign vascular tumor arising from capillaries around facial nerve, most commonly in the area of the geniculate fossa. Hemangioma limited to the lumen of the internal auditory canal is rare, usually located in the fundus. Larger hemangiomas involve the bone of the petrous pyramid and may extend within the internal auditory canal. Adult patients with internal auditory canal hemangioma present with relatively rapid onset of peripheral facial nerve paralysis and concomitant sensorineural hearing loss. Other vascular abnormalities within the internal auditory canal (e.g., varix malformation, aneurysm arising from the labyrinth artery) are extremely rare and may mimic the symptomatology of a schwannoma. |

Endolymphatic papillary sac tumor | Inhomogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass with intratumoral bone spicules, centered in the fovea of the endolymphatic sac in the presigmoid, posterior surface of the petrous bone. The tumor erodes the posterior wall of temporal bone and infiltrates surrounding bone and connective tissue. Larger tumors spread to involve middle ear and inner ear, internal auditory canal, jugular foramen, and extend into the cerebellopontine angle cistern. | Rare, slow-growing, locally aggressive papillary adenomatous tumors that do not metastasize. Most endolymphatic sac tumors are sporadic. Seven percent of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease will develop endolymphatic sac tumor. If the endolymphatic sac tumor is bilateral, von Hippel-Lindau disease is present. Patients usually present in the fourth decade with sensorineural hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, pulsatile tinnitus, or vertigo. |

Otosclerosis | ||

Fenestral otospongiosis/otosclerosis | In active fenestral otosclerosis, the most frequent lesion is seen as a hypodensity in the labyrinthine capsule at the anterior margin of the oval window. It tends to extend posteriorly, fixing the stapes footplate and sometimes invading and thickening the footplate. Lucent lesions can also occur on the promontory or at the round window. Late, chronic bone CT findings are heaped upon new bone with dense, ossific plaques along oval and round window margins. It may obliterate the windows and bulge into the middle ear cavity. | In otosclerosis, the dense layer of ivory-like endochondral bone that surrounds the labyrinthine capsule is replaced by foci of spongy, vascular, irregular new bone. It is commonly a symmetrical disease. In fenestral otosclerosis (80%–90% of cases), the promontory, facial nerve canal, and oval and round windows are involved. Patients (M:F = 1:2) usually present in the second to third decades with bilateral progressive conductive hearing loss, tinnitus, and normal findings on otoscopic examination. |

Cochlear otospongiosis/otosclerosis | Focal radiolucencies in the otic capsules; when severe, the cochlea is completely surrounded by a ring of hypodense bone (“double-ring” sign). The demineralization may also be seen around the vestibule, semicircular canals, and internal auditory canal. Later, in the sclerotic phase, these foci may undergo remineralization and become indistinguishable from the normal otic capsule. | Retrofenestral otosclerosis is much less common and involves the bone around the cochlea or around the membranous labyrinth. It is invariably associated with fenestral otosclerosis. Becomes symptomatic in the second and third decades with bilateral, progressive, mixed hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. May become worse during pregnancy or lactation. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Asymmetric fatty marrow | Nonpneumatized petrous apex with fatty marrow (petrous apex is considered pneumatized if it contains one or more air cells). | Approximately 33% of people have pneumatized petrous apices, of which 4% to 7% are asymmetrically pneumatized. Nonpneumatized petrous apex with fatty marrow is an incidental CT/MRI finding. Asymptomatic by definition. |

Congenital cholesteatoma | Smooth, sharply marginated, expansile lesion, centered within the petrous apex, hypodense with respect to brain, round or oval in shape, with lack of contrast enhancement. Large lesions may erode the horizontal petrous internal carotid artery canal, otic capsule, internal auditory canal, or jugular foramen. | Most petrous apex cholesteatomas are congenital. Absence of previous otologic disease and normal tympanic membrane are necessary to consider a cholesteatoma congenital. If congenital variant, may simultaneously affect mastoid area. Very rare petrous apex lesion usually associated with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, headache, and aural fullness. Large lesions may cause dysfunction of CN X, XI, and XII if the lesion extends posterior or CN III, IV, and V if it extends anteromedially. Patients are 20 to 50 y old. |

| Acquired cholesteatomas, which involve the petrous apex, are aggressive and may extensively erode the petrous bone. | Acquired cholesteatomas of the petrous apex are rare and usually occur by extension from the middle ear space along the supralabyrinthian air cell system along the anterior epitympanic space. Facial nerve dysfunction occurs in 20% to 50% of cases. |

Subarcuate artery pseudolesion | Curvilinear vascular canal that passes through arch of superior semicircular canal from subarcuate fossa on posterior wall of petrous temporal bone in a lateral posterosuperior direction. The ease of visualization is dependent upon both the canal’s size and the extent of adjacent pneumatization. | Normal temporal bone osseous canal through which passes the subarcuate artery (supplies otic capsule, semi-circular canals, and posterior wall vestibule). |

Benign obstructive processes | ||

Effusion (trapped fluid) | Nonexpansile fluid-attenuation opacification of the air cells. Cortical margin and air cell trabeculae are preserved. No contrast enhancement of petrous apex or adjacent meninges. | Most common radiographically identified lesion of the petrous apex. Presumed to represent sterile residual fluid collection in petrous apex air cells left behind after remote otomastoiditis with subsequent obstruction of the connection between the middle ear and apical air cells. Asymptomatic by definition. All ages affected. Incidental CT/MRI finding. |

Mucocele | Smooth, expansile lesion, isodense to CSF, homogeneous, without contrast enhancement within the petrous apex. The presence of a large air cell on the opposite side can suggest a mucocele. | Mucocele of the petrous apex is very rare. |

Cholesterol granuloma | Sharply and smoothly marginated ovoid lesion, isodense to brain, homogeneous and free of calcification without internal contrast enhancement, centered within and expanding the petrous apex especially posteriorly, where the overlying bone may be paper thin or absent. Large lesions may erode foramen magnum, hypoglossal canal, jugular foramen, and internal acoustic canal. (MRI: high signal on T1-, T2-, and diffusion-weighted images.) | Pneumatized petrous apex air cells are required. Inflammatory granulation tissue forms secondary to repeated hemorrhage leading to an expansile petrous apex lesion. Patients are young to middle-aged adults and present with sensorineural hearing loss and/or tinnitus, vertigo, and facial twitching. A previous history of chronic otomastoiditis is common. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Apical petrositis | Middle ear and both mastoid and petrous air cells are usually involved simultaneously and opacified with peripheral contrast enhancement. As the infection progresses to osteomyelitis, trabecular breakdown and erosive cortical changes of the destroyed petrous apex become apparent. Advanced disease may cause possible complications of epidural empyema, abscess, or venous sinus thrombosis. | Apical petrositis is an acute infection of the pneumatized air cells of the petrous apex, usually caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Patients are children or adolescents with acute otomastoiditis or adults with chronic suppurative ear or following mastoidectomy. They present with infectious symptoms and manifest some or all of the symptoms of Gradenigo syndrome: purulent otomastoiditis, otorrhea, abducens palsy, and deep facial and retro-orbital pain. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Meningioma | Extra-axial mass, either globose (spherical) or en plaque, attached to the petrous apex. May extend anteriorly under the temporal lobe and posteriorly along the edge of the tentorium. On CT scan, meningiomas typically are isodense to slightly hyperdense to brain. The density is generally homogeneous and sharply marginated. Typically, contrast produces a homogeneous, intense enhancement. Calcification may be present in a number of forms. Small punctate (psammomatous) calcifications are common. Occasionally, large nodular calcifications may be present. Dense calcification of the entire tumor that obscures contrast enhancement is not uncommon. Bony changes may be hyperostotic or osteolytic. | Although rarely originating from the petrous apex, meningiomas may infiltrate the region. Affect middle-aged women. Can remain clinically silent for many years. |

Meckel cave trigeminal schwannoma | Dumbbell-shaped isodense or hypodense mass with smooth expansion of Meckel cave and petrous apex. May erode the superior petrous ridge. The marked contrast enhancement may be homogeneous, inhomogeneous, or even ring-shaped. Calcification is rare. | Meckel cave trigeminal schwannomas arising from the gasserian ganglion tend to enlarge superiorly into the middle cranial fossa and extend posteriorly into the posterior cranial fossa. Patients present in the third and fourth decades (mean age 44 y). Common symptoms include continuous facial pain and paresthesias. |

Facial nerve hemangioma | Poorly marginated enhancing soft tissue mass of the petrous pyramid, emanating from geniculate fossa around intact otic capsule to the petrous apex with diffuse, mottled demineralization with multiple distinctive amorphous “honeycomb” bone changes. | Rare intratemporal benign vascular tumor arising from capillaries around facial nerve, most commonly in the area of the geniculate fossa. Patients are adults and present with relatively rapid onset of peripheral facial nerve paralysis. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Chordoma | Expansile multilobulated inhomogeneous solid midline tumor centered in the clivus with lytic bone destruction, sharp margins of erosion, and at least some enhancement. Intralesional fragmented destroyed bone, hemorrhage, and mucoid areas may occur. Expanding tumor invades or displaces jugular foramen and petrous apex laterally. | Rare malignant bone tumors arising from notochordal remnants; 35% arise in the skull base as a destructive midline mass (clivus, sellar region, sphenoid sinus, nasopharynx, maxilla, and paranasal sinuses). Most commonly occur between the ages of 30 and 50 y (2:1 male predilection). Symptoms include ophthalmoplegia and headache. |

Chondrosarcoma | Heterogeneously enhancing, relatively dense solid tumor located offthe midline at the petro-occipital synchondrosis or near the spheno-occipital synchondrosis with arc or ringlike calcifications (50%). The infiltrating skull base mass shows usually a sharp, narrow, nonsclerotic transition zone to the adjacent normal bone. | Constitutes 6% of all skull base tumors. Typically centered in the petro-occipital and petrosphenoid synchondroses with frequent extension into the petrous apex or clivus. Most commonly occur between the ages of 10 and 80 y, with a mean age of 40 y (no gender predilection). Symptoms include insidious onset of headaches and cranial nerve palsies (usually CN VI; also III, V, VII, and VIII). May complicate Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. Osteosarcoma is rare in the temporal bone; may be seen secondarily in the setting of prior irradiation or Paget disease. |

Plasmacytoma | Solitary intraosseous, usually homogeneous, mildly hyperdense expansile soft tissue mass with osteolytic destruction; scalloped, poorly marginated, nonsclerotic margins; and moderate, homogeneous or less commonly heterogeneous enhancement. Peripherally displaced osseous fragments may be seen. | Most common locations in head and neck are the sinonasal region, skull base (especially sphenoid and petrous temporal bones), and calvarial marrow space. Progression to multiple myeloma is common. Most present in the fifth to ninth decade, with male predilection. Symptoms include local pain and headache. Temporal bone lesions may present with sensorineural hearing loss and clival lesions with sixth cranial nerve palsy. |

Metastases | Most petrous apex metastases appear lytic or permeative with bone cortex destruction and a varying amount of associated enhancing soft tissue mass. Breast cancer may be primarily lytic, blastic, or mixed. Metastatic prostate cancer is primarily osteoblastic but may be lytic. Other metastatic types that may be blastic are lung (carcinoid), stomach, bladder, and some CNS malignancies. | The petrous apex is the most common area in the temporal bone for hematogenous metastases to be found. In order of frequency, metastatic lesions of the following tumors have been found: breast, lung, kidney, prostate, and stomach. Metastasis to the temporal bone occurs late in the disease process, and there is usually either physical or radiologic evidence of other systemic lesions. Invasive extracranial lesions are most often primary nasopharyngeal tumors that extend into the cranial cavity by erosion of the skull base and petrous apex. |

Metabolic/dysplastic lesions | ||

Paget disease | Paget disease of the temporal bone typically starts at the petrous apex and progresses inferolaterally. In the osteolytic stage, CT reveals decreased bone density due to demineralization. In the mixed phase, there can be a heterogeneous appearance of mixed lysis and sclerosis (“cotton wool” appearance). The sclerotic form of Paget disease is uncommon in the temporal bones. Bone thickening can be seen in the mixed and sclerotic phase. Involvement of the otic capsule with demineralization and encroachment upon the middle ear are late manifestations. Ossicular involvement may be limited to the stapes footplate. | Skull involvement alone or in association with changes elsewhere in the skeleton is quite common (28%–70%). The temporal bones may be involved by Paget disease, particularly the petrous apex, squamous portion, and mastoid area. Onset uncommon before age 40 (4:1 male predilection). Symptoms include hearing loss (sensorineural, conductive, or mixed), vertigo, and tinnitus. Malignant degeneration in ~1% of cases. |

Fibrous dysplasia | All varieties of fibrous dysplasia are characterized by localized or diffuse increased bone volume of the affected temporal bone with thinning of the overlying cortical bone. Pagetoid fibrous dysplasia (50%) shows either classic “ground glass” or mixed sclerotic-cystic appearance. Sclerotic fibrous dysplasia (25%) shows homogeneous density approaching cortical bone. Cystic fibrous dysplasia (50%) shows a spherical or ovoid lucency surrounded by a dense bony shell. Lesion expansion may occasionally result in stenosis of the external and/or internal auditory canal, encroaching on the middle ear and ossicular chain, and obliteration of the otic capsule. In active phase, heterogeneous enhancement may be present. | The skull and facial bones are involved in 10% to 25% of cases of monostotic fibrous dysplasia and in 50% of polyostotic variety. Involvement of the temporal bone, however, is relatively rare. Most active in children and young adults; often ceases to grow by age 20 to 25 (3:1 female predilection). Symptoms include bulging, pain, and tenderness of the temporal area, stenosis of external auditory canal with recurrent otitis, and hearing loss (conductive, sensorineural, or mixed). May be associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. Malignant transformation is rare (< 0.5% of cases). |

Osteopetrosis | The petrous bone shows a complete lack of pneumatization and a homogeneous diffuse, sclerotic appearance. Progression of the disease results in narrowing of the internal auditory canals. | Osteopetrosis is a rare bone disease characterized by formation of new bone while resorption of bone is diminished. |

Miscellaneous lesions | ||

Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Destructive bone process with sharply defined “punched out” rather than expansile appearance. Fragments of bone within the heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue component are common. | Mastoid complex and temporal bone lesions are common. Bilateral disease occurs in 30%. Skull, skull base, mandible, maxilla, and vertebral body involvement also may occur. May be diffuse or multiple in more severe cases. Petrous apex disease is less common. Usually occurring in young patients (first decade, 2:1 male predilection). Symptoms include otalgia, otorrhea, hearing loss (conductive or sensorineural), facial nerve palsy, and vertigo. |

Petrous carotid artery aneurysm | Fusiform or focal enlargement of the petrous internal carotid artery canal. Expansile mass with extension into adjacent structures. Curvilinear calcifications in the aneurysm wall. Enhancement is equivalent to other arteries. CTA shows aneurysmal dilation of petrous internal carotid artery. | Uncommon. Congenital aneurysm may be associated with additional intracranial aneurysms or anomalies, including neurofibromatosis and connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome and fibromuscular dysplasia. Acquired aneurysms are posttraumatic or postinfectious. Presenting symptoms vary, depending on the adjacent structures and vessels involved: sensorineural hearing loss, headache, nasal congestion, and midface pressure and pain. A ruptured aneurysm may occur with otorrhagia, epistaxis, and neurologic deficit. |

Petrous apex cephalocele | Hypodense, nonenhancing expansile lesion, centered outside petrous apex and extending from Meckel cave. The trigeminal notch and inferior border of the porus trigeminus are eroded, and the sharply marginated lesion extends a variable distance into the anterosuperior petrous apex. CT cisternogram may show contrast opacification of the defect in the petrous apex, proving communication with the subarachnoid space and Meckel cave. | Congenital or acquired, usually unilateral herniation of the posterolateral wall of Meckel cave into petrous apex. Rare lesion usually identified as an asymptomatic incidental nonoperative finding on MRI. In complicated cases, symptoms are trigeminal neuralgia, CSF otorrhea (with communication between cephalocele and middle ear), and recurrent meningitis. |

Petrous apex arachnoid cyst | Hypodense, expansile lesion, without contrast enhancement at the petrous apex with smooth, noninvasive bony excavation. | Arachnoid cysts of the petrous apex are extremely rare lesions. Can be associated with petrous apex cephalocele. The cyst becomes symptomatic when the enlargement causes compression and dysfunction of neural structures (trigeminal neuralgia, midface paresthesia, and hearing loss) or alterations in CSF dynamics (CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea). |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Asymmetric jugular bulb | Temporal bone CT reveals normal, asymmetrically large jugular bulb, with intact cortical margins and jugular spine of jugular foramen. Normal, usually right-sided, asymmetrically large sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb demonstrate similar contrast enhancement characteristics as internal jugular vein. | Size of jugular foramen is greatly variable, even from side to side, and is associated with a corresponding large or small jugular bulb. Asymmetric jugular bulb is a normal variant, found incidentally on brain MRI during workup for unrelated symptoms. Large, asymmetric jugular bulb provides setting where MRI signal from slow, complex venous flow may mimic pathology (jugular bulb pseudolesion). |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

High-riding jugular bulb | Jugular bulb reaching above the level of the inferior tympanic rim with a smoothly marginated bone defect behind the internal auditory canal. The bony plate separating the bulb from the middle ear cavity is preserved. The jugular bulb enhances to the same degree as the sigmoid sinus and internal jugular vein. | Normal variant, not to be confused with a mass lesion (present in 6% of temporal bones). More common on the right side. Does not change in size. Asymptomatic anatomical variation. |

Dehiscent jugular bulb | Soft tissue mass low in the middle ear, contiguous with the internal jugular vein through a focal jugular (sigmoid) plate defect. The other margins of the adjacent jugular foramen are smooth and intact. Commonly seen with high-riding jugular bulb. The superolateral outpouching demonstrates similar enhancement characteristics to jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, and internal jugular vein. | Congenital vascular pseudomass. Does not grow with time. This is usually asymptomatic, but it may cause pulsatile tinnitus or conductive hearing loss. Otoscopically, a retrotympanic vascular mass may be seen in the lower part of the middle ear behind the intact tympanic membrane. |

Jugular bulb diverticulum | Well-corticated, focal polypoid mass extending from cephalad jugular bulb (usually superiorly and medially) into surrounding temporal bone just behind the internal auditory canal. The jugular bulb itself may be high. CTA shows fingerlike projection offjugular bulb. | Congenital vascular pseudomass; rare venous anomaly. More common on the left side. Does not change in size. Most common incidental finding, but may present with nonpulsatile tinnitus, sensorineural hearing loss, or symptoms mimicking Ménière disease. Otoscopic examination is negative. |

Primary cholesteatoma (epidermoid) | Primary cholesteatoma originating in the immediate vicinity of the jugular foramen presents as smooth and rounded, homogeneous mass of low CT density (density less than that of brain), associated with expansion of the jugular fossa and erosion of the posteroinferior aspect of the petrous pyramid and adjacent occipital bone. Cholesteatomas do not enhance with contrast. | Primary cholesteatomas of the jugular fossa area are very rare. Acquired cholesteatomas of the temporal bone with infralabyrinthine extension inferior to the cochlea and internal auditory canal may break into the jugular fossa and cause Vernet syndrome with unilateral paresis of CN IX to XI. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

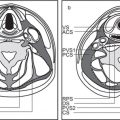

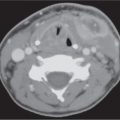

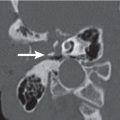

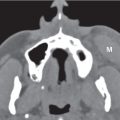

Glomus jugulare paraganglioma Fig. 5.42a, b | Lobulated, homogeneous, intensive enhancing soft tissue mass (computer-generated density–time curve reveals a high, early, arterial peak), poorly marginated with cortical erosion, irregular enlargement of the jugular fossa, and permeative-destructive change of adjacent bone with no sclerosis. Jugular spine erosion is common. Routes of extension are superolateral through the floor of the middle ear, medial to the posteroinferior aspect of the petrous pyramid, and posterior with involvement of the occipital bone, hypoglossal canal, and foramen magnum. Inferior extension within and along the jugular vein occurs often. Up to 17% protrude extradurally into the middle and posterior cranial fossa. Glomus tumors frequently invade the jugular vein and obliterate the vessel partially or completely. Glasscock-Jackson classification Glomus jugulare paraganglioma: Type I: small tumor invading jugular bulb, middle ear, and mastoid process. Type II: tumor extending under internal auditory canal; may have intracranial extension. Type III: tumor extending to petrous apex; may have intracranial extension. Type IV: tumor extending beyond petrous apex into clivus or masticator space; may have intracranial extension. | Glomus jugulare paraganglioma (GJP) is a benign tumor arising from paraganglia surrounding the jugular bulb (in 85% of cases), Arnold nerve (branch of CN X), or Jacobson nerve (branch of CN IX). When middle ear extension occurs, such a tumor is called a glomus jugulotympanicum paraganglioma. GJP is the most common jugular foramen tumor and the second most common temporal bone tumor (after acoustic schwannoma). Multicentricity in sporadic forms is present in 10%. When familial (inherited as an autosomal dominant disease), multicentricity amounts to 25% to 50%. Increased risk of paragangliomas in MEN1 and NF1. Malignant transformation with regional lymph node metastases is seen in 4%. GJPs occur at any age but have a predilection for middle-aged women. Glomus jugulare tumors present with Horner syndrome and deficiencies of CN IX, X, XI, and XII. Cranial neuropathy of CN VII and VIII are seen less often. Glomus jugulotympanicum tumors present with pulsatile tinnitus, conductive hearing loss, and vascular retrotympanic mass. Endocrine syndrome may occur in 1% to 3% of cases. |

Jugular foramen schwannoma | Schwannomas are fusiform or “dumbbell” tumors with well-defined margin, isodense or hypodense to brain, and dense contrast enhancement. Large tumors often show intramural cystic or fatty degeneration. Schwannomas cause smooth remodeled enlargement of the jugular foramen with well-defined, scalloped bone margins. Coronal bone CT plane may show amputation of lateral jugular tubercle (“bird’s beak”). The vector of tumor growth follows a general craniocaudal course of CN IX to XI. The tumor may project superiorly into the posterior cranial fossa with extension into the cerebellopontine angle cistern and encroach on the brainstem. Some tumors grow inferiorly from jugular foramen into nasopharyngeal carotid space. | Second most common jugular foramen tumor (glomus jugulare paraganglioma first). Glossopharyngeal nerve most common nerve of origin. These tumors may become large before producing symptoms in middle-aged individuals. Sensorineural hearing loss may occur before clinical involvement of the nerves of the jugular foramen. Cranial nerve neurofibromas are extremely rare. |

Hypoglossal schwannoma | Hypoglossal schwannomas are “dumbbell” tumors with well-defined margin, isodense or hypodense to brain, and dense contrast enhancement. Large tumors often show intramural cystic or fatty degeneration. They cause expansion and remodeling of the hypoglossal canal without osseous destruction. Hypoglossal schwannoma follows the course of CN XII with cephalad growth into anteroinferior basal cistern and cerebellopontine cistern and caudal growth into nasopharyngeal carotid space. Extension to involve the middle ear is not a feature of these tumors. | Schwannomas can also arise within the hypoglossal canal. |

Jugular foramen meningioma | Poorly circumscribed, hyperdense jugular foramen mass (lobulated and en plaque morphotypes) with uniform, strong contrast enhancement. Meningiomas usually cause permeative-sclerotic bone changes at jugular foramen and of adjacent bone. Hyperostosis of adjacent jugular foramen cortex may be present. Dural-based tumor spread in basal cistern is most common. Meningiomas may also extend centrifugally in all directions from jugular foramen along dural surfaces and through surrounding bones. Less commonly, meningioma pedunculates up into basal cistern. Inferior spread dumbbells into nasopharyngeal carotid space. | Meningioma is the third most common jugular foramen mass. Meningiomas arise from arachnoid cap cells in meninges of skull base or CN IX to XI at the jugular foramen. They are typically large at presentation and more frequent in women, who are in the fourth to sixth decades of life, with complex cranial neuropathy involving CN IX to XI; less commonly, CN VII, VIII, and XII. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Metastases | Metastases to the jugular foramen may be lytic, sclerotic, or mixed with variable enhancing, invasive jugular foramen mass. | Metastases to the jugular foramen occur most commonly with advanced metastatic disease and are usually part of other metastases in the skull base. Most common primary locations are breast, lung, kidney, and GI tract. Rapid symptom onset (often lower cranial nerve deficits). Retrograde perineural spread from malignancies of the face and oral cavity may give rise to jugular foramen metastases. Lymphoma, melanoma, and squamous cell carcinoma show this type of tumor extension. Enlargement and pathologic enhancement of the nerve root, as well as jugular foramen enlargement, are suggestive of perineural spread. |

Plasmacytoma | Lytic bone destruction with scalloped, poorly marginated, nonsclerotic margins, along with enlargement of the jugular foramen due to a mildly hyperdense soft tissue mass with moderate homogeneous enhancement. | Plasmacytoma may manifest as a solitary lesion in the base of skull (especially sphenoid body and petrous temporal bone). Rarely, this tumor is located in the jugular fossa. Present in fifth to ninth decades. More common in male patients. |

Hemangiopericytoma | CT findings are similar to glomus tumors. There is lytic destruction with expansion of the jugular foramen. The soft tissue mass is irregular with marked contrast enhancement. | Hemangiopericytoma is a rare tumor in the jugular fossa. The tumor affects both genders equally and occurs in the fourth to sixth decades of life. At least 50% of hemangiopericytomas are malignant. |

Chondrosarcoma | Chondrosarcoma of the jugular foramen reveals irregular bone destruction with enlargement of the foramen. The soft tissue component is relatively dense with variable contrast enhancement. Speckled, linear, or arclike calcifications may occur in tumor matrix. | Chondrosarcomas of the skull base characteristically arise from the petrosphenoidal or petro-occipital fissures. They may extend posterolaterally to involve the jugular foramen at its medial aspect. Chondrosarcomas confined to the jugular foramen are extremely rare tumors. Clinical profile: middle-aged patient with insidious onset of headaches and cranial nerve palsies. Expanding midline chordoma, centered in the clivus, may present an erosive and destructive lesion of the jugular fossa. |

Nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma | This tumor originates in the high posterolateral nasopharyngeal mucosal space, just below the skull base. CT shows an invasive soft tissue mass with simple skull base erosion, lytic destructive upward invasion of basisphenoid and basiocciput, and intracranial extension. Occasionally, sclerosis may be invoked in the skull base. | Nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma can extend to involve the skull base, producing lower cranial nerve symptoms. Isolated extension to the jugular fossa is uncommon. Other secondary tumors with prominent extension (e.g., malignant parotid neoplasms and malignant tumors of the external auditory canal or middle ear cavity) may invade the base of the skull and temporal bone, including the jugular foramen. |

Related posts:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree