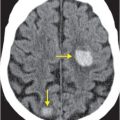

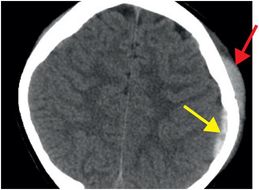

Diagnosis: Left parietal epidural hematoma with overlying fracture

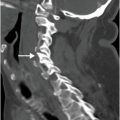

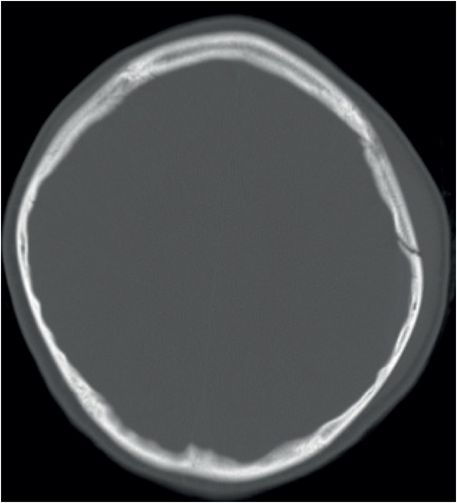

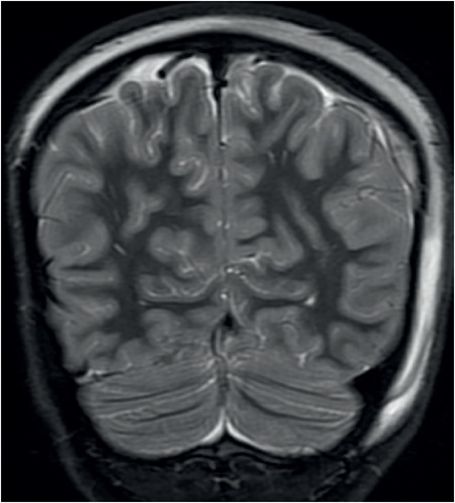

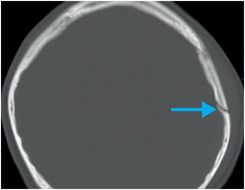

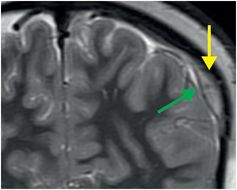

Noncontrast axial CT in brain window (left image) demonstrates a hyperdense extra-axial collection over the left parietal convexity (yellow arrow). A small subgaleal hematoma is present superficially (red arrow). Bone windows (middle image) reveal an overlying non-displaced fracture (blue arrow). MRI was performed for clarification of which extra-axial space this hematoma occupied, as its small size made this difficult to discern on CT. T2-weighted coronal MRI (right image) shows that the hematoma (yellow arrow) is in the epidural compartment, superficial to the black line of the dura (green arrow).

Discussion

Overview of epidural hematoma

Epidural hematomas (EH) are intracranial extra-axial blood collections located between the periosteal layer of the inner calvarial table and the dura. 90% are due to arterial injury, while the remainder result from damage to a dural venous sinus near dural attachments. Trauma is the usual cause, with overlying skull fracture in greater than 85–95% of cases.

Arterial epidural hematoma

The typical injury that results in epidural hematoma is a skull fracture with laceration of the middle meningeal artery (MMA). In children, traumatic MMA injury may result from stretching of the vessel without an overlying skull fracture. Given the location of the MMA, the majority of epidural hematomas are located along the temporal or temporo-parietal convexity.

Venous epidural hematoma

Venous EH usually spans multiple cranial compartments and may cross the falx and tentorium. It is commonly seen in the posterior (transverse or sigmoid sinus injury) and middle cranial (sphenoparietal sinus injury) fossae and near the vertex (superior sagittal sinus injury). Posterior fossa EH are less common (5–10%) than supratentorial EH (90–95%). Because they result from slower venous bleeding, they tend to present in a delayed fashion, hence their worse prognosis. Venous EH are always located next to a dural sinus that has been transgressed by a fracture line. The involved sinus may be displaced by the collection but is usually not occluded.

Clinical presentation of epidural hematoma

In 50% of cases, patients with EH present in a classical fashion: with an initial brief loss of consciousness followed by an asymptomatic period (“lucid interval”). After the lucid interval, precipitous decline in mental status develops rapidly. The overall mortality of unilateral EH is approximately 5%, rising to approximately 15–20% in cases where EH is bilateral. Prompt recognition and treatment of EH is essential to ensure good outcome. Epidural hematomas less than 1 cm in maximal thickness may not require surgical intervention. In some centers, a diagnostic angiogram may be performed to assess for active bleeding and possible therapeutic intervention such as embolization of the MMA.

Imaging of epidural hematoma

On imaging, EH appear as lenticular or biconvex hyperdense extra-axial collections. They do not cross suture lines, as dural attachments act as barriers in the absence of suture injury. Rarely, EH can occur simultaneously with subdural hematomas. The combined biconvex and crescentic configuration of a mixed epidural–subdural hematoma has been named the “CT comma” sign.

When it is small in size, it may be difficult to localize a hematoma to the epidural or subdural compartment by shape and confinement by dural structures. In these cases, MRI may be needed for clarification, as in the index case. On T2-weighted MRI, EH will be superficial to the thin hypointense dura, while subdural hematoma will be subjacent.

Extra-axial hematomas, both subdural and epidural, produce variable mass effect on the underlying brain. Careful assessment for herniation, a potentially fatal complication, should be performed in all cases.

Injuries associated with EH include contrecoup subdural hematomas and cerebral contusions. Air pockets within EH suggest paranasal sinus or mastoid fractures.

In the acute setting, two-thirds of EH are hyperdense (50–80 HU). If there is active extravasation, a swirl of hypodense non-coagulated blood may be seen within the hyperdense collection (“swirl” sign). This sign may also be seen in anemic or coagulopathic patients. Over time, the EH will evolve into a mixed-density, and eventually, a hypodense collection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree