Diagnosis: Diaphragmatic hernia

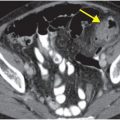

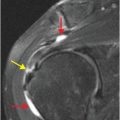

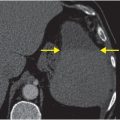

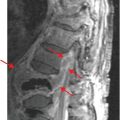

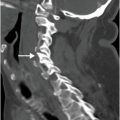

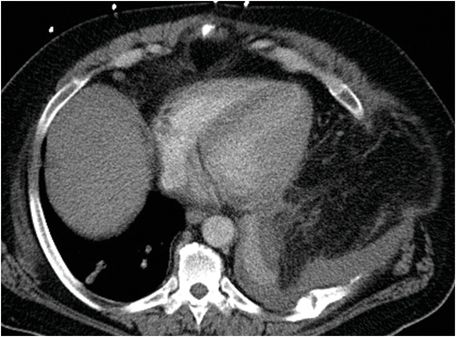

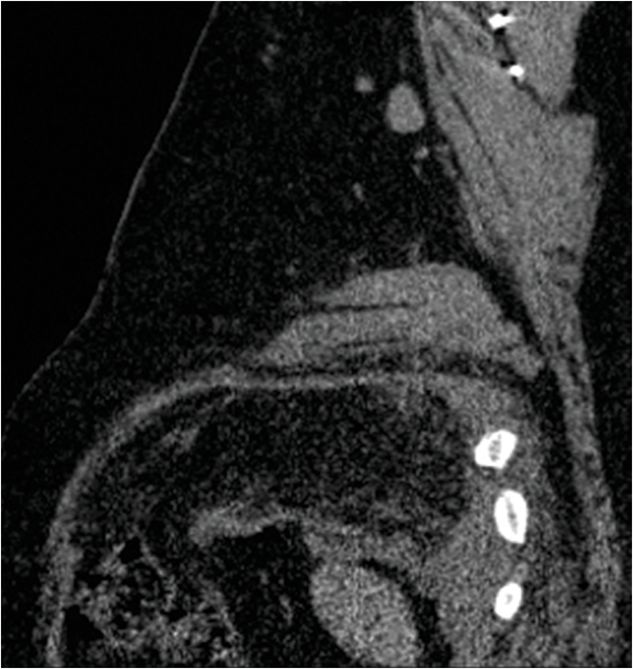

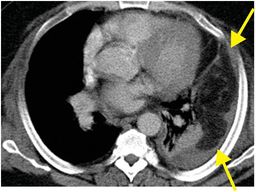

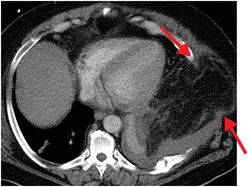

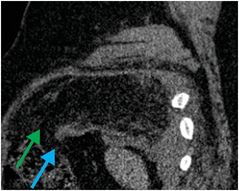

Axial enhanced CT images (left and middle) demonstrate mixed solid and fat attenuation (yellow arrows) within the left thoracic cavity, associated with a small pleural effusion and enhancing compression atelectasis of the left lung base. There is herniation of the fat through the anterolateral chest wall (red arrows). Sagittal image from the same examination (right) shows a large defect in the anterolateral aspect of the diaphragm (blue arrow), with resultant thickening and folding of the shortened free edge of the diaphragm (“dangling diaphragm” sign). Mesenteric fat has herniated into the thorax (green arrow) through the diaphragmatic defect.

Discussion

Overview of diaphragmatic injury

Diaphragmatic hernia is a disruption of the diaphragmatic muscular or tendinous fibers resulting in communication between the thoracic and abdominal cavities.

Diaphragmatic hernia may result from penetrating injury (e.g., knife or gunshot wound) causing direct disruption of diaphragmatic fibers, or blunt trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accident) abruptly producing a pressure gradient between the thorax and abdomen. Secondary diaphragmatic injury may also occur due to diaphragmatic laceration from fractured ribs in trauma patients. A closed glottis at the time of trauma causes an elevated pressure gradient and further increases the risk of diaphragmatic injury. Chronic cough is a much less common cause of diaphragmatic rupture.

Diaphragmatic injury is more readily diagnosed and more common on the left side, where herniation may include the stomach, colon, omentum, or spleen. Additionally, there is often congenital embryologic weakness in the left posterolateral aspect of the diaphragm, increasing susceptibility to injury. Conversely, the large size of the liver may offer protection against right diaphragmatic injury. Complications of diaphragmatic hernias include respiratory insufficiency, bowel obstruction, and incarceration with ischemia of the herniated viscera.

Diagnosis of diaphragmatic injury may be delayed when caused by blunt trauma. In contrast to penetrating injuries, which are typically surgically explored, blunt diaphragmatic injury may initially present without herniation and may be diagnosed later when herniation of abdominal contents occurs. Careful evaluation of the sagittal and coronal CT reformations is especially helpful in detecting subtle diaphragmatic disruption.

Imaging of diaphragmatic injury

Both direct and indirect signs of diaphragmatic injury can be detected by CT.

A direct sign of diaphragmatic injury is a segmental diaphragmatic defect, which may be associated with muscle retraction (usually manifested as thickening) and hemorrhage. The “dangling diaphragm” sign is another direct sign of diaphragmatic injury and represents curling of the free edge of the ruptured diaphragm.

Indirect signs of diaphragmatic injury include the “collar” sign and the “dependent viscera” sign. The first describes the waist-like constraint around herniated abdominal contents, and the latter, the apposition of herniated contents against the posterior thoracic wall due to loss of diaphragmatic support.

Diaphragmatic scalloping (variation of costal insertion of fibers) may mimic injury due to indentation on underlying organs. Absence of a true diaphragmatic defect on sequential images helps to confirm this normal variant.

Clinical synopsis

The patient was diagnosed with diaphragmatic rupture caused by severe coughing spells due to pertussis respiratory infection. The patient was treated with intensive antibiotic and steroid courses. After symptomatic improvement, the patient underwent surgical repair of the diaphragm and chest wall.

Self-assessment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree