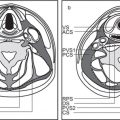

6 Orbit and Globe(Table 6.1 – Table 6.2)

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Anophthalmos | Absence of a normal eye and optic nerve. In its place, there is a mass of amorphous soft tissue. The lens is absent. The extraocular muscles are thin; the muscle cone is narrowed and elongated. The bony orbit is small with thick walls. The optic chiasm may be hypoplastic or absent. The corpus callosum may be dysgenetic. The contralateral eye may be normal, small, or also absent. | Anophthalmos results from an insult to the developing globe during the first 4 weeks of gestation. |

Microphthalmos | Simple primary microphthalmos: Small optic globe, anatomically correct, associated with small, under-developed orbit. Usually bilateral. Associated with cataracts, but with no concurrent anomalies. Simple secondary microphthalmos: The globe tends to be small but normally shaped; the lens is almost always identifiable; the posterior chamber of the eye tends to be hyperdense. There are no recognizable internal structures. The bony orbit and retroocular structures have normal size and configuration. Phthisis bulbi represents an end-stage atrophic globe that has undergone extensive degenerative changes: small, irregularly shaped globe with heavy subretinal calcification or ossification; the sclera becomes markedly thickened, irregular, and calcified. Complex microphthalmos with coloboma: All colobomatous eyes are small, enophthalmic, and malformed. The lenses are dysplastic. The size of the globe is inversely proportional to the size of the coloboma: the larger the outpouching, the smaller the globe. The bony orbit is also slightly small, the optic nerve and the extraocular muscles are thin. Complex microphthalmos with cyst: Small malformed globe associated with a large paraocular cyst (isodense to vitreous). The inner walls of the cyst may enhance. Proptosis may be present (depending on the size of the associated cyst). In most cases, only one eye is involved. Cryptophthalmos refers to severe microphthalmia. A rare congenital anomaly. Usually occurs bilateral. | Congenital causes: coloboma, congenital rubella, PHPV, ROP, retinal folds, Lowe syndrome, Norrie disease, and Warburg syndrome. Occurs as an isolated disorder or may be associated with other craniofacial anomalies (hemifacial microsomia, Goldenhar syndrome, hypomelanosis of Ito, Proteus syndrome, and Aicardi syndrome). Acquired causes: optic nerve atrophy, sequelae of trauma, infection, surgery, and radiation therapy. |

Congenital cystic eye | Solid and/or cystic mass that completely fills the orbit and protrudes anteriorly. Retroocular structures are not present or are extremely atrophic. The bony orbit is enlarged, and its walls are thin. The contralateral eye may be normal, small, or absent. | An extremely rare variant of anophthalmos in which the optic vesicle degenerates into a mass of disorganized, solid or cystic neuroectodermal, glial, and angiomatous elements. Orbital teratoma and microphthalmos with posterior cyst may exhibit similar imaging characteristics. |

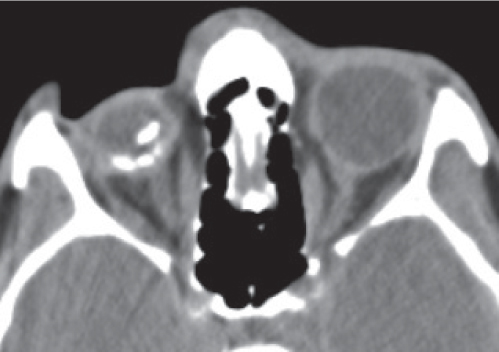

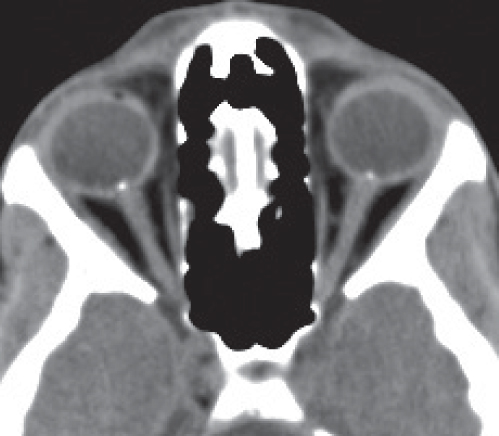

Coloboma | Colobomas appear as outpouchings of variable size and shape arising from the posterior globe. When bilateral, the colobomas are commonly asymmetric in size. All colobomatous eyes are small: the larger the outpouching, the smaller the globe. | Coloboma is a defect in closure of the fetal optic fis-sure. No gender predilection; may be associated with numerous other ocular, central nervous system (CNS), facial or systemic anomalies, including chromosomal syndromes. Differential diagnosis: buphthalmos, staphyloma, microphthalmic cyst, retrobulbar duplication cyst, retroocular dermoid, hydrops, and arachnoid cyst of the optic nerve sheath. |

| Optic disk coloboma: Deformity of the posterior globe with focal small defect at optic nerve head insertion with crater- or funnel-shaped outpouching of vitreous, with fluid density; small unless associated with a retrobulbar microphthalmos cyst. Frequently bilateral. Associated findings: microcornea, microphthalmia, and optic tract and chiasm atrophy. |

|

| Choroidoretinal coloboma: Excavation separate from or extends beyond disk. Typically bilateral. “Morning glory” disk anomaly: Usually unilateral congenital disk defect distinct from optic disk coloboma: funnel-shaped excavation, larger than simple optic disk coloboma, and central tuft of glial tissue within defect. Associated findings: aniridia, PHPV, and retinal detachment. | Rare. Female and right-side predilection. May present with leukocoria. Associated abnormalities: basal cephaloceles, moyamoya, and agenesis of corpus callosum. |

Staphyloma | The eye shows a focal bulge posterior. Associated with axial myopia, staphylomas generally occur on the temporal side of the optic disk, but they are also seen anteriorly or along the equator of the eye. The sclera is thin at that level. | A staphyloma is a type of focal buphthalmia. Staphylomas may be seen with axial myopia, glaucoma, trauma, scleritis, and necrotizing infections. They have a high risk for chorioretinal degeneration, choroidal hemorrhage, posterior vitreous detachment, and retinal detachment. May present with visual loss in children and adults. |

| Peripapillary staphyloma: Deep excavation of the posterior wall of the globe with connection to the vitreous cavity at optic nerve head. Usually unilateral. | Peripapillary staphyloma is an isolated congenital disk anomaly with extremely rare incidence. The disk is at the bottom of the excavated defect. |

Coats disease | CT imaging characteristics are that of a retinal thickening with retinal detachment due to leakage of fluid with high cholesterol and lipoproteinaceous content, which presents as homogeneous hyperdensity involving part of or the entire vitreous in a normal-sized globe. The leaves of the detachment may mildly enhance. The lack of calcifications and lack of an enhancing mass in the globe are key findings to exclude retinoblastoma. | Coats disease is an idiopathic retinal disorder, characterized by telangiectatic, leaky retinal vessels that lead to exudative retinal detachment. It is usually a unilateral disorder that occurs in boys (peak age 6–8 y), rarely in adults (40–60 y). Leukocoria is a presenting symptom. |

Norrie disease (retinal dysplasia) | Bilateral microphthalmia with hyperdense (hemorrhagic) vitreous, retinal detachment, optic nerve atrophy, small lens with retrolental pear-shaped bulge, and shallow anterior chamber. | Rare X-linked recessive syndrome associated with bilateral leukokoria and microphthalmia, retinal malformation, deafness, and mental retardation or deterioration. Developmental anomaly of the brain may also be present. |

Warburg syndrome | Bilateral microphthalmia with retinal detachment, subretinal or vitreous hemorrhage, sometimes with layered blood levels. PHPV may be associated. The congenital nonattached retina exhibits a characteristic narrow, funnel-shaped or triangular intravitreal image adjacent to hyaloid (Cloquet) canal. | Rare autosomal recessive disorder consisting of bilateral leukokoria and microphthalmia, congenital unilateral or bilateral retinal nonattachment, profound mental retardation, lissencephaly, hydrocephaly, and with death in infancy. |

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV) | CT findings are unilateral (rarely bilateral) microphthalmos (can be absent), lens and anterior chamber hypoplasia, and increased density of the entire vitreous without calcification. A contrast-enhancing cone-shaped central retrolental intravitreal density is thought to represent the persistence of fetal tissue in Cloquet canal. Posterior hyaloid or retinal detachment with fluid levels may be associated. | Rare ocular malformation with persistence of various portions of the primary vitreous with hyperplasia and extensive proliferation of the associated embryonic connective tissue due to incomplete regression of embryonic ocular blood supply in Cloquet canal. It can reflect an isolated congenital defect or a manifestation of more extensive ocular or systemic involvement (e.g., trisomy 13, Norrie disease, Warburg syndrome, primary vitreoretinal dysplasia, and other congenital defects). Presents at birth or in infancy with leukocoria (it is the second most common cause of leukocoria), poor vision, and a small eye. |

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) | Bilateral, often asymmetric microphthalmia with increased density of the vitreous chamber from previous hemorrhage or from neovascular ingrowth. Retinal detachment is frequently associated. A PHPV may be present. Lenticular and/or choroidal dystrophic calcifications are rare but may occur in the late stage of the disease. | Retrolental fibroplasia usually manifests in premature infants who received supplemental oxygen therapy after birth. It accounts for 3% to 5% of the cases of childhood leukokoria. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Scleritis | Thickened, enhancing sclera. There may be associated thickening of Tenon capsule (sclerotenonitis), serous retinal detachment, disk swelling, or serous choroidal detachment. Posterior nodular scleritis is a focal, necrotizing, granulomatous inflammation. Unlike uveal melanoma or ocular lymphoma, no contrast enhancement is found. | Scleritis may be bacterial, fungal, or viral in origin, an idiopathic scleral inflammation, or associated with systemic disease (autoimmune disorders: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis; other connective tissue diseases; metabolic conditions, e.g., gout; or Wegener granulomatosis, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn disease, Cogan syndrome, and sarcoidosis). May be unilateral or bilateral, anterior or posterior, acute or chronic. Commonly affects women. |

Endophthalmitis | Increased density of the vitreous without a mass. The uveoscleral coat may be thickened and demonstrate increased contrast enhancement (focal enhancement with abscess). Associated choroidal, retinal, and posterior vitreous detachment may be present. Variable degree of increased density in periocular soft tissue structures. | Refers to an intraocular infectious or noninfectious inflammatory process predominantly involving the vitreous cavity or anterior chamber. Exogenous endophthalmitis: due to surgical or nonsurgical penetrating trauma. Endogenous endophthalmitis: hematogenously from an infectious focus. Organisms: staphylococci, streptococci, meningococci, gram negatives, helminthic parasite, and cysticercosis. |

Ocular toxocariasis (sclerosing endophthalmitis) | Spectrum of CT imaging characteristics: • Diffuse increased density of the eye by homogeneous intravitreal density, due to detached retina, organized vitreous, and inflammatory subretinal exudates. Absence of calcification. • Localized or diffuse ill-defined mass without enhancement. • Chronic abscess, seen as an irregularity of the uveoscleral coat with diffuse or local thickened, slightly enhanced uveosclera. | Uncommon, usually bilaterally ocular infection of children (average age 6 y) in close contact with dogs. The infection results from ingestion of eggs of the nematode Toxocara canis. The second-stage larva of Toxocara and the death of the larva result in a wide spectrum of intraocular inflammatory reactions (granuloma, abscess, and diffuse inflammatory infiltration of the choroids and sclera). Leukocoria is a presenting symptom. Imaging findings of toxocariasis may be similar to those seen in Coats disease and noncalcific retinoblastoma. Positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is helpful in differential diagnosis. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Choroidal (cavernous) hemangioma | May present in two different forms: • As a circumscribed or solitary type, typically located posterior to the equator of the globe in the juxtapapillary or macular region of the fundus. The lenticular, solid soft tissue mass in the wall of the globe demonstrates intense contrast enhancement. May show peripheral calcification. • As a diffuse angiomatosis, often associated with facial nevus flammeus or variations of the Sturge–Weber syndrome. May involve as a flat, intensely enhancing mass the three components of the uvea and, occasionally, nonuveal tissues, such as the episclera, conjunctiva, and limbus. Unlike the melanomas, choroidal hemangiomas are not seen as an obvious lesion on noncontrast CT scans. Following contrast infusion, the hemangiomas exhibit bright enhancement. May be concealed by retinal detachment. | Congenital vascular hamartomas, typically seen in middle-aged to elderly individuals; isolated ocular finding or in association with neurocutaneous syndromes. Cavernous hemangiomas of the choroids are very uncommon, nonprogressive, benign lesions. |

Choroidal osteoma | Choroidal osteoma (choriostoma) appears as a sharply demarcated, flat, platelike calcified thickening of the posterior choroids, typically in the juxtapapillary region. No soft tissue infiltration. | Rare benign choroidal tumor consisting of mature bone, found predominantly in otherwise healthy young women ages 10 to 30 y; 25% are bilateral, 15% multifocal. Can cause painless vision loss. |

Uveal nevus | Small flat or minimally elevated lesion located most often in the posterior third of the choroid. Usually too little to be visualized. | Benign congenital lesion, usually diagnosed in the first decade of life. Most commonly misdiagnosed lesion to be enucleated under the presumption of malignant melanoma. |

Ciliary body adenoma | May present as a well-defined tumor with moderate contrast enhancement arising from the ciliary body behind the iris, encroaching upon the lens. | Rare lesion. Although benign, adenoma of the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium can behave aggressively locally, causing cataract and vitreous hemorrhage. The most common presenting symptom is visual loss. |

Uveal leiomyoma | Tends to occur in the ciliary body and peripheral choroidal region rather than in the posterior choroids. Appears as a protuberant, well-defined, elliptoid-ovoid mass that is isodense with respect to brain, with contrast enhancement. | Extremely rare benign tumor of the uveal tract, usually diagnosed in young adult women with decrease of visual acuity. Patients may develop cataract, secondary glaucoma, and retinal detachment. |

Uveal schwannoma | Uveal schwannoma usually affects the ciliary body and peripheral choroids rather than the posterior choroids. The tumor appears as a solitary, well-defined, oval lesion, isodense with respect to the brain, with contrast enhancement. Displacement of the lens and bulge of the globe may be seen. Extraocular growth should not be seen. | Schwannoma of the uveal tract is a rarely encountered disease entity lesion that may be initially confused with malignant uveal melanoma. Most patients are women (second to sixth decades). Slowly progressive impairment of visual acuity can be explained by displacement of the lens and progression of an anterior subcapsular cataract. Rapid visual loss may be due to retinal detachment secondary to uveal schwannoma. |

Choroidal cyst | Unilateral or, less commonly, bilateral cystic lesion that may cause retinal detachment. | Very rare lesion that may be mistaken for a solid choroidal tumor. |

Retinal (capillary) hemangioma | This lesion, usually located in the midperipheral retina, is often small in size (1–2 mm) and can be inapparent on noncontrast scans, except the tumor is calcified or ossified. After contrast injection, it demonstrates significant enhancement. May be associated with exudates and retinal detachment. | Capillary hemangiomas of the retina, histologically similar to cerebellar hemangioblastomas, are extremely rare intraocular tumors, usually associated with von Hippel–Lindau disease (50% bilateral involvement, multiple in the affected eye in one third). These lesions can enlarge. Their propensity to bleed may cause exudative retinal detachment, glaucoma, cataract, and uveitis. |

Retinal astrocytoma | Usually very small, thin, and translucent, or more dense, multilobulated, and minimally vascular nodule near the optic nerve. Single or multiple. Unlike retinoblastoma, it rarely grows. It may be associated with infiltration of the optic nerve, exudative retinal detachment, hemorrhage, and calcification. | Also called ocular (astrocytic) hamartoma. It is a rare, benign retinal tumor, occurring in children (8–15 y). May present as an isolated ocular pathologic finding (sporadic in one third of the cases) or in association with both tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis type 1. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

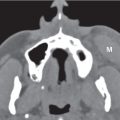

Retinoblastoma | Calcified intraocular mass, hyperdense to vitreous in a normal-sized globe of a child younger than 3 y of age is highly suggestive of retinoblastoma. Punctuate, finely speckled, or diffuse, dense calcification is noted in 90%–95%. In contrast-enhanced CT scan, the tumor shows slight to moderate heterogeneous enhancement. Retinal detachment may occasionally be the only manifestation. Endophytic growth pattern of retinoblastoma: Irregular, solid, and heterogeneous peripheral intraocular mass, usually posterior to the equator, with inward protrusion into vitreous; associated with vitreous seeding. Exophytic retinoblastoma: Outward growth of the intraretinal tumor into the subretinal space; associated with a progressive retinal detachment. Diffuse infiltrating form: Rare; the tumor grows along the retina appearing as a placoid mass (which simulates inflammatory or hemorrhagic conditions), often without calcifications and usually outside the typical age group. Extension with optic nerve enlargement, abnormal soft tissue in orbit and intracranial extension may occur in 25% of cases, without calcifications. | Most common intraocular malignancy of infancy and childhood (average age at diagnosis 13 mo), congenital in origin, rarely occurs in adults, without gender or side predilection. Presents in 95% under the age of 5 y with leukocoria, severe vision loss, and eye pain. Unilateral in 70% to 75%, bilateral in 25% to 30%. Trilateral retinoblastoma refers to the association of bilateral retinoblastoma with a pinealoblastoma. Tetralateral retinoblastoma: bilateral disease plus pineal and suprasellar tumor. Sporadic: 60% of retinoblastomas. Inherited: 40% of retinoblastomas. Essentially all bilateral and multilateral disease. With risk of second malignancy (osteosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and melanoma): 20% to 30% in nonirradiated patients, 50% to 60% radiation-induced. |

Ocular melanoma | Intraocular focal, well-defined, elevated dome, crescentic, flat, polypoid or mound shaped, solid, peripheral mass of the posterior segment, extending into the vitreous, with broad choroidal base, hyperdense to vitreous, with diffuse moderate enhancement. Mushroom shape implies penetration through Bruch membrane. Calcification is rare. Retinal detachment is frequently coexisting but often indistinguishable from the neoplasm without contrast enhancement. Transscleral penetration or optic nerve tumor invasion may be seen (5%). | Most common primary intraocular malignancy in adult Caucasian (peak incidence sixth and seventh decade), with slight male preference. The tumor is almost always unilateral, with 85% arising from the choroids, 10% from the ciliary body, and 5% from the iris. Congenital melanosis, ocular melanocytosis, ocudermal melanocytosis, and uveal nevi are conditions that may predispose to uveal melanoma. Presents with painless vision disturbance. |

Ciliary body adenocarcinoma | May present as a well-defined, multilobulated mass with moderate contrast enhancement involving the ciliary body, the posterior and anterior chamber angle, and the iris. The invasive tumor can spread into choroid, corneoscleral, and episcleral tissues, as well as into the orbit and intracranially. | Ocular adenocarcinomas are extremely rare malignant lesions that may arise from the pigmented and nonpigmented epithelium of the ciliary body, iris, or retina. Associated uveitis, glaucoma, hemorrhage, and exudative retinal detachment are not uncommon. This intraocular neoplasm should be considered in middle-aged adults with a long-standing phthisical eye with an epibulbar mass and for proptosis of recent duration. |

Medulloepithelioma | Nonteratoid medulloepithelioma (diktymoma): Appears as a dense, noncalcified mass in the region of the ciliary body, with moderate to marked enhancement. May be associated with cysts in the anterior part of the vitreous, lens coloboma, and lens subluxation. Teratoid medulloepitheliomas (30%–50%): with cartilaginous differentiation and associated calcification; appears as a dense, irregular, calcified mass in the region of ciliary body. In advanced medulloepithelioma involving the vitreous cavity and the retina, other causes of intraocular calcified lesions (retinoblastoma, CMV chorioretinitis, toxocara endophthalmitis, ROP, choroidal osteoma, and retinal astrocytoma) cannot be excluded. Retinal detachment is an associated finding seen in advanced cases. | Rare nonhereditary, unilateral embryonic neoplasm, malignant in most cases; usually diagnosed in the first decade of life (mean age 4 y); without racial, gender, or side predilection. It typically arises from the ciliary body epithelium but may also occur as a posterior mass in the retina or in the region of the optic nerve head and optic nerve. Presents with cataract, cyclitic membrane formation, and glaucoma. Ciliary body medulloepitheliomas may be associated with intracranial neoplasms (CNS medulloepithelioma and pinealoblastoma) and CNS malformations (agenesis of the corpus callosum, schizencephaly, and mass-like soft tissue prominence of the quadrigeminal plate). Extremely rare, these tumors can occur in adults and may mimic melanoma, adenoma or adenocarcinoma of the ciliary epithelium, mesoectodermal leiomyoma, neurilemoma, metastatic carcinoma, and intraocular inflammation, such as granulomatous uveitis or TB granuloma. |

Ocular metastases | Metastatic tumor to the globe most commonly involves the posterior temporal portion of the uveal tract near the macula. The lesions are often multiple and bilateral (one third of cases) with small, flat, disk-like or lentiform shaped, thickened areas of increased density, and associated with exudative detachment. Less common presentations include circular uveal thickening. Contrast enhancement is variable, ranging from minimal to moderate. | Most patients with ocular metastases have a known primary malignancy with systemic metastases. The most common sources of secondary tumor within the eye are the lung and breast. In children, ocular metastases occur with neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, Wilms tumor, and leukemia. |

Leukemia | CT imaging of leukemic infiltration of the uvea, choroids, and retina reveals a localized or diffuse thickening of these structures, often bilateral. Intraocular hemorrhage due to hematologic alterations may be present. | Orbital involvement in leukemia is not common. It occurs in children with acute lymphatic leukemia and in adults with chronic lymphatic leukemia. Leukemia may involve every tissue of the eye; the choroids are the most consistently involved layer on histopathology. Intraocular findings include iritis and vitritis. |

Ocular lymphoma | Orbital CT findings are usually normal and noncontribu-tory but may include an ill-defined soft tissue density of the vitreous chamber, choroidal-scleral thickening, widening of the optic nerve, elevated chorioretinal lesions, and posterior vitreous and retinal detachment. | Primary intraocular lymphoma, considered part of primary CNS lymphoma, is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, a rare type of non–Hodgkin lymphoma. Involvement includes retina, subretinal space, vitreous, uvea, and optic nerve. Bilaterality occurs in about 90% of cases. Most patients diagnosed to have intraocular lymphoma are elderly (mean age 63 y) and have symptoms of vitritis with blurred vision and vitreous floaters, and a history of systemic lymphoma or CNS involvement. |

Trauma | ||

Eyeball injury | • Ocular hemorrhage Anterior chamber: distortion of the contours or increased density of the anterior chamber (anterior hyphema). Vitreous chamber hemorrhage: increased density of the vitreous without layering. Choroidal hematoma: hyperdense rounded or globular intraocular mass. Density of blood decreases with time. • Ocular detachment Retinal detachment. Choroidal detachment. | Intraocular hemorrhage may be spontaneous, post-traumatic, or associated with bleeding disorders and a variety of ocular disorders. |

| • Traumatic lens dislocation Abnormal position of the lens. • Eyeball rupture Loss and flattening of the normal spherical contour of the eyeball (“pear” or “flat tire” sign). CT may show air within the globe and intraocular blood. | The lens is more frequently subluxated than completely dislocated. Penetrating trauma or severe blunt trauma may cause laceration of the sclera with escape of the vitreous and decrease in the intraocular pressure. |

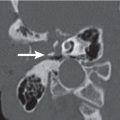

| • Foreign body CT may confirm the presence or absence of a foreign body and provide information with regard to its composition and location. It may also demonstrate other associated injuries and possible complications. • Phthisis bulbi In the chronic phase, the posttraumatic eyeball may appear small, deformed, retracted, calcified, and shrunken. | Foreign body can be classified as • Organic (wood, dirt, or other vegetable matter) • Inorganic (metallic ([steel, lead, iron, aluminum, and other metal alloys]) and nonmetallic (glass, plastic, stone, or other minerals). Phthisis bulbi is not unique to trauma. It is an end-stage appearance of an eyeball that has undergone degeneration and disorganization because of trauma, infection, inflammation, or tumor. |

Miscellaneous lesions | ||

Macrophthalmia | Diffuse enlargement of the optic globe. Pseudomacrophthalmia: Apparent enlargement of one eye can occur with proptosis or when the contralateral eye is relatively small. | Macrophthalmia can result from glaucoma in children or may be seen as an isolated entity, secondary to massive intraocular tumor, or in association with neurofibromatosis. Axial myopia, characterized by elongation of the globe in the anteroposterior dimension, is the most common cause of eye enlargement with no intraocular masses. Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular tumor to produce generalized eye enlargement. Buphthalmos (“ox eye”): diffuse extreme enlargement of the eye in children secondary to increased intraocular pressure, caused by congenital or infantile glaucoma. |

Proptosis | Abnormal anterior protrusion of a normal-sized globe (extension > 21 mm anterior to the interzygomatic line on axial scans at level of lens). Axial proptosis: Globe projected away from the center of the orbit. Nonaxial proptosis: associated with localized masses elsewhere in the orbit. | Associated with thyroid ophthalmopathy, pseudo-tumor, infection (bacterial or fungal), sarcoidosis, Erdheim–Chester disease, Wegener granulomatosis, vasculitis and connective tissue diseases, lymphoproliferative disease, orbital mass lesions, including benign or malignant neoplasms, vascular lesions, abscesses, hematomas, fractures, mucoceles, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrous dysplasia, and sphenoorbital dysplasia of neurofibromatosis type 1. |

Enophthalmos | Relative depression of the globe back into the orbit. | May occur in orbital blow-out fracture, silent sinus syndrome, neurofibromatosis with absence of part of the sphenoid bone, breast carcinoma metastases, and Cockayne syndrome. Pseudoenophthalmos: end-stage-contracted globe. |

Posterior hyaloid detachment | Blood or other fluid accumulation occurs in the posterior hyaloid space between the detached posterior hyaloid membrane and sensory retina. On CT, the noncalcified mobile lesion tends to accumulate in the most dependent portion and may depict gravitational fluid–fluid levels. The detached posterior hyaloid membrane may be seen as an intravitreal curvilinear image extending toward the optic disk. | In adults older than 50 y, usually caused by accelerated vitreous liquefaction with myopia, surgical and nonsurgical trauma, and intraocular inflammation. In infants often associated with PHPV. |

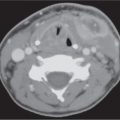

Retinal detachment | Blood or other fluid accumulation occurs in the subretinal space between the sensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium. The leaves of the detached and folded sensory retina are limited at the ora serrata and at the optic disk and converge toward the optic disk, thereby producing a characteristic V-shaped configuration. | A rhegmatogenous retinal detachment occurs due to a hole, tear, or break in the retina that allows fluid to pass from the vitreous space into the subretinal space. Rhegmatogenous detachment is the most common. Risk factors include myopia, previous cataract surgery, and ocular trauma. A tractional retinal detachment occurs when fibrovascular tissue, caused by an injury, inflammation, or neovascularization, pulls the sensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium. May occur in proliferative diabetic or sickle cell retinopathy. Secondary, serous, or exudative retinal detachment results in fluid accumulating underneath the retina without the presence of a hole, tear, or break. It occurs due to inflammation, injury, vascular abnormalities, and primary or metastatic choroidal tumors. |

Choroidal detachment | Choroidal detachment is caused by the accumulation of fluid or blood in the potential suprachoroidal space. The choroid is firmly attached at the ciliary body and tethered at the vortex veins. This results in the typical appearance of choroidal detachment: it appears as a smooth, ring-shaped, crescentic, or dome-shaped, semilunar area of variable attenuation values. The detached leaves do not extent to the region of the optic nerve, form a U or, in a more advanced stage, the “kissing choroids” sign, and are restricted at the level of the scleral attachments of the vortex veins. The detached choroids can extend frontal to the ciliary body and result in ciliary detachment. | Ocular hypotony is the essential underlying cause of serous choroidal detachment and may be the result of ocular inflammatory disease (uveitis, scleritis, and Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome), accidental perforation of the eye, ocular surgery, or intensive glaucoma therapy. Other causes are myxedema, nanophthalmos, and idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome. Hemorrhagic choroidal detachment may occur spontaneously or as a complication of ocular surgery, ocular trauma, hemoglobinopathies, and anticoagulation therapy. |

Macular degeneration | Irregular lesion of increased density, similar to uveal melanoma, related to hemorrhage in the retinal and subretinal space. Frequently complicated by scar formation or liquefaction of the vitreous with posterior hyaloid detachment. The lesion may show moderate to marked contrast enhancement. | Disciform degeneration of the macula in the elderly is a leading cause of legal blindness. The earliest changes at the macula are hyalinization and thickening of Bruch membrane, followed by ingrowth of choroidal neovascularization. |

Optic nerve head drusen | Discrete, flat, round calcification of the optic nerve disk. Bilateral in 75% of cases. | Acellular accretions of hyalinelike material on or near the surface of the optic disk that become calcified. Most cases are idiopathic. Occasionally, drusen are associated with ocular diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa. May be familial and asymptomatic or present with headache, visual field defects, and pseudopapilledema. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Optic perineuritis | Tubular thickening (uniform enlargement) or fusiform thickening (lens shaped, tapering at either end) of the optic nerve-sheath complex. May show perineural contrast enhancement, producing a form of “tram-track” sign. | Unusual localized form of orbital pseudotumor. In contrast to optic neuritis, pain is exacerbated with retrodisplacement of the globe, and patients are slightly older (mean age 39.5 y). Involvement of the optic nerve-sheath complex is rarely also found with viral, tuberculous, and syphilitic infections, radiation therapy, and sarcoidosis. |

Optic neuritis | CT findings are usually normal but may include both mild swelling and enhancement of the optic nerve with irregular borders. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality to evaluate optic neuritis. | May be sporadic or a harbinger of multiple sclerosis. Patients (mean age 30 y) present with acute loss of visual acuity, evolving over hours to days, ipsilateral eye pain, and dyschromatopsia. Significant recovery of vision is typical. Approximately 50% of patients with idiopathic optic neuritis develop multiple sclerosis; 15% to 25% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) initially present with optic neuritis; 70% to 90% of patients with MS develop optic neuritis at some point. Devic syndrome (neuromyelitis optica): bilateral acute optic neuritis with transverse myelitis. Other, less common causes of optic neuritis include ischemia, pseudotumor, sarcoidosis, radiation therapy, systemic lupus erythematosus, viral infection (varicella, herpes, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-related optic neuropathy), toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, syphilitic neuritis, and Sjögren syndrome. |

Neoplasms | ||

Optic nerve glioma | Smooth, sharply marginated, tubular, fusiform, globular, or excrescent enlargement of the optic nerve, which is isodense to brain with slight to moderate contrast enhancement. Cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and calcification are uncommon. Kinking (buckling) and tortuosity can be noted. Intracranial extension along the optic pathway through the eroded optic canal is common with a dumbbell shape. Extension of glioma into the posterior optic pathway (chiasm, optic tracts, lateral geniculate bodies, or even optic radiations) may form a large mass growing into the adjacent brain. Bilateral involvement is more common in neurofibromatosis type 1. | Uncommon childhood disease (4% of all orbital tumors) but accounts for 80% of primary tumors of the optic nerve presenting with decreased vision and axial proptosis. The peak incidence is from 2 to 8 y of age, with slight female predominance. One third of patients have neurofibromatosis type 1; 15% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 have optic nerve or optic chiasm glioma. Histologically, childhood optic nerve glioma is commonly a pilocytic astrocytoma, whereas the much more rare adult optic nerve glioma (peak incidence 40–50 y of age, with male predominance) tends to be glioblastoma with much more aggressive behavior, bilateral, and predominantly involves the intracranial optic nerves and chiasm. |

Ganglioglioma | The optic nerve shows diffuse enlargement unlike that observed in optic nerve glioma and optic nerve sheath meningioma. | Ganglioglioma is a rare tumor affecting the optic nerve. |

Optic nerve hemangioblastoma | Well-enhanced, sharply demarcated, pear-shaped solid mass in the optic nerve. Apex tumors may grow unusually like a dumbbell, thereby widening the optic canal. In addition, optic nerve hemangioblastoma may be associated with optic nerve enlargement, chiasmal or optic tract edema, cysts, angiomatosis retinae, infratentorial hemangioblastomas, and cysts of the abdominal viscera. | Very rare tumor of optic nerve, seen in patients with von Hippel–Lindau disease or arises sporadically. More common in men. The age of diagnosis is between the third and fifth decades. Patients experience gradually progressive loss of vision either to blindness or surgical intervention, as well as proptosis with a dull eye pain. |

Secondary optic nerve tumors | Metastasis of the optic nerve may appear as an irregular soft tissue mass with invasion of adjacent structures. | Secondary optic nerve tumors more frequent (82%) than primary optic nerve tumors (18%). These tumors include • Hematogenous metastases to the optic nerve–sheath complex (rare) • Direct extension from ocular tumors • Compression or invasion by tumor adjacent to the nerve in the orbital cavity • Extension of tumor from the sellar/parasellar area through the subarachnoid space • Seeding of tumor within the subarachnoid space from sources outside the neural axis, principally from carcinomas • CNS tumors extending to the chiasm and optic nerves, including primary neuroectodermal tumors, glioblastoma, and gliomatosis cerebri. |

Optic nerve sheath meningioma | Optic nerve sheath meningiomas are commonly seen as a diffuse tubular enlargement along the intraorbital portion of the optic nerve, but growth can be fusiform or as a localized, eccentric expansion of the optic nerve, often at the orbital apex, simulating a tumor within the orbit that has encroached on the optic nerve. They are infiltrative and may result in an irregular and serrated appearance. Meningiomas tend to be hyperdense on CT and frequently reveal globular, linear, plaquelike, or granular calcifications (calcification within the mass virtually excludes optic glioma). Meningiomas often show homogeneous and intense contrast enhancement surrounding the nonenhancing optic nerve embedded in the tumor (“tram-track” sign). Extension into the optic canal may cause enlargement and occasionally hyperostosis of the margin of the canal. | Optic nerve sheath meningiomas represent < 1% of all meningiomas and constitute 3% to 5% of orbital tumors. They may originate primarily from the meninges along the orbital segment of the optic nerve or may extend secondarily into the orbit from the intracranial meninges. Bilateral optic nerve sheath meningiomas are uncommon. They are the second most common primary neoplasm of the optic nerve-sheath complex and occur predominantly between the ages of 30 and 50 y but may occur at any age. Childhood optic nerve meningioma is often associated with neurofibromatosis type 2 and behaves aggressively. There is a female predominance (3–5:1). Patients present with optic nerve atrophy, progressive loss of vision over months, disk edema, or pallor and proptosis. Hemangiomas and hemangiopericytomas rarely originate in the perioptic nerve sheath. |

Lymphoproliferative disease | Lymphomatous optic neuropathy may produce a thickened, enlarged, and enhanced optic nerve sheath surrounding the nerve that does not enhance. | Lymphoma and leukemia may infiltrate the optic nerve–sheath complex as part of systemic disease. In leukemia, diffuse infiltration of the optic nerve can lead to rapid loss of vision. The spectrum of orbital disease in non–Hodgkin lymphoma includes well-defined mass lesions and diffusely infiltrative lesions in the extraconal and/or intraconal space, lacrimal gland masses, and conjunctival involvement. |

Trauma | ||

Optic nerve injury | • Optic nerve injury from fracture fragments or foreign body that may impinge on the optic nerve. • Mass effect from edema and hemorrhage within the optic nerve sheath that may lead to ischemia. • Optic nerve avulsion. | Optic nerve injury is loss of vision or visual impairment secondary to direct or indirect damages of the optic nerve. |

Miscellaneous lesions | ||

Distended optic nerve sheath | Bilateral or unilateral, tortuous, enlarged optic nerve–sheath complex with central density reflecting optic nerve. | Bilateral dilation of the perioptic nerve subarachnoid space may be idiopathic or result from increased intracranial pressure (intracranial mass lesions, hydrocephalus, malignant hypertension, diffuse cerebral edema, or increased venous pressure), elevated CSF protein level, and pseudotumor cerebri. Unilateral distention of the optic sheath may result from orbital apex obstruction by fracture or mass lesion of the optic nerve, inflammatory lesions, hydrops, optic atrophy, and arachnoid cyst. |

Optic nerve sheath meningocele | Prominent focal or segmental enlargement of the dural arachnoid sheath around the optic nerve. The lumen is filled with CSF. May be associated with empty sella and enlarged subarachnoid cisterns, such as gasserian cisterns. | May occur primarily or secondarily in association with other orbital processes, such as meningioma, optic nerve pilocytic astrocytoma, and hemangioma. May present with changes in the visual acuity, visual field, and optic nerve appearance. |

Related posts:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree