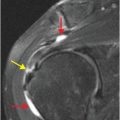

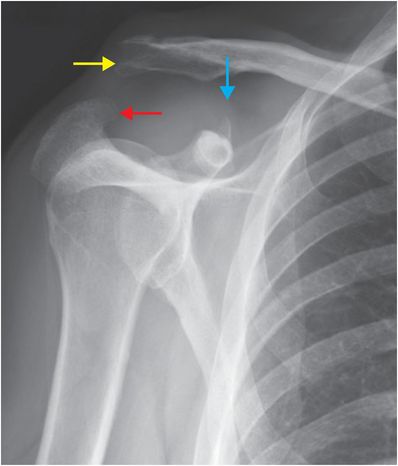

Diagnosis: Type III acromioclavicular joint separation with coracoclavicular ligament avulsion

Magnified view of an AP chest radiograph demonstrates elevation of the distal clavicle (yellow arrow) relative to the acromion (red arrow) with widening of the coracoclavicular space. There is osseous irregularity at the superior aspect of the coracoid (blue arrow), consistent with coracoclavicular ligament avulsion.

Discussion

Overview of acromioclavicular (AC) joint separation

AC joint separation, generically referred to as “shoulder separation,” describes a spectrum of injuries that most commonly occur as a result of a fall onto the lateral aspect of the shoulder with the arm in flexion and adduction.

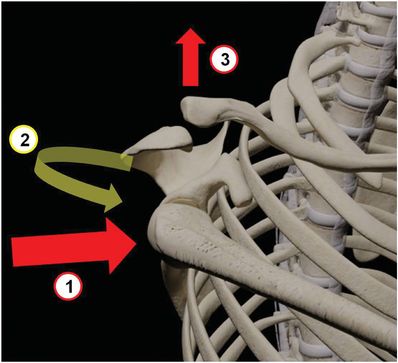

Impact onto the lateral aspect of the shoulder (1), as seen with a fall onto the shoulder, produces protraction of the scapula (2), with compressive force transmitted to the AC joint, causing superior displacement of the distal clavicle (3) with respect to the acromion.

Classification of acromioclavicular injuries

Acromioclavicular injuries are most commonly classified according to the Rockwood classification system.

Type I: AC ligament sprain.

Type II: AC ligament tear with intact coracoclavicular (CC) ligament.

Type III: AC and CC ligament tears with widening of the coracoclavicular distance up to 100% compared to the contralateral side.

Type IV: AC and CC ligament tears with posterior displacement of clavicle.

Type V: AC and CC ligament tears with superior displacement of clavicle of greater than 100% compared to the contralateral side.

Type VI: AC and CC ligament tears with inferior/subacromial displacement of clavicle.

Imaging of acromioclavicular injuries

Measurement thresholds of 6 mm and 7 mm have been suggested as upper limits of normal for acromioclavicular joint space on frontal radiographs for women and men, respectively. Similarly, a coracoclavicular space of 13 mm has been shown to be the upper limit of normal. Some authors have indicated that measurements exceeding these values suggest AC or CC ligament injury. However, the orthopedic surgery literature favors comparison with the (presumed normal) contralateral side. Greater than a 25–50% measurement discrepancy with the normal side has been suggested to correlate with ligament injury. This method is problematic in cases of bilateral injury, or when contralateral imaging is unavailable.

Type I injuries are radiographically occult or may show soft tissue swelling at the AC joint, with the diagnosis dependent on the patient’s symptoms and clinical suspicion.

Type II injuries can be ambiguous, showing only minimal widening of the AC space.

Weight-bearing radiographs (with weights held in hands) have been suggested to aid in detection of occult Type III injuries; however, studies have shown mixed results regarding efficacy.

Type III, IV, and VI injuries may be difficult to distinguish clearly on radiographs, as differentiation depends on the relative three-dimensional displacement of the clavicle. In type IV injuries, the clavicle is displaced posteriorly, while in type VI injuries the distal clavicle is dislocated inferiorly, underneath the coracoid process. CT may be required to discriminate between these types. CT angiography should be considered if a type IV injury (posterior clavicular displacement) with vascular compromise is suspected.

Type V injuries can be diagnosed with a 100–300% increase in the CC interspace on frontal radiographs.

MRI has been shown to demonstrate ligamentous and associated soft tissue injury, and can be useful in resolving diagnostic ambiguity between type II (intact coracoclavicular ligament) and type III (torn coracoclavicular ligament) injuries, particularly if surgical intervention is being contemplated. MRI is not indicated for uncomplicated injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree