Chondroectodermal Dysplasia

Cleidocranial Dysplasia

Congenital Insensitivity to Pain

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Diastrophic Dysplasia

Down Syndrome

Epiphyseal Dysplasias

Homocystinuria

Klippel-Feil Syndrome

Marfan’s Syndrome

Melorheostosis

Mucopolysaccharidoses

Os Odontoideum

Osteogenesis Imperfects

Osteopetrosis

Pyknodysostosis (Pycnodysostosis)

Scheuermann’s Disease

Turner’s Syndrome

van Buchem’s Disease

Achondroplasia

BACKGROUND

Classic, heterozygous, autosomal-dominant achondroplasia is the most common dwarfing skeletal dysplasia and typically is evident at birth. The condition results from a defect at the 2.5 Mb locus of chromosome 4p16.3. 74 The name (a-, meaning “not,” chondroplasia, meaning “formation of cartilage”) implies that a complete lack of normal cartilage formation exists. This is not the case, although the hallmark of the condition is hypochondrogenesis, with a decreased rate of formation of essentially normal cartilage.

Achondroplasia usually is evident at birth and generally is compatible with a normal life expectancy; therefore patients with this condition may be seen at any age. Achondroplasia is recognized easily clinically and is differentiated from other dwarfing dysplasias readily.

IMAGING FINDINGS

General.

Imaging findings in achondroplasia reflect gross anatomic changes. The ilia are broad and squared, with constricted sciatic notches. The pelvic inlet has a “champagne glass” configuration. The sacrum is horizontal and deeply seated in the pelvis. The ribs are broad and short, resulting in a diminished anteroposterior (AP) dimension of the thorax. The sternum is short and broad. The long and tubular bones are shortened and the developing metaphyses flared. Limb shortening is more profound proximally than distally (rhizomelic micromelia). 140

Epiphyses.

Epiphyseal changes may resemble a variety of epiphyseal dysplasias. Broad, short proximal phalanges, with short middle phalanges of the feet and (more classically) the hands may occur. This results in a clinically apparent, trident-shaped hand in infants. (The trident is a three-pronged spear wielded by the fish-god of classical mythology.)

Limb lengthening.

As limb-lengthening procedures pioneered by the Russian physician Ilizarov have become more widely used, clinicians may encounter patients with atypical postoperative long bone changes. 29,53 A number of studies have shown impressive gains in limb length in patients treated with this procedure. 5,75,194

Spine.

Plain films highlight most of the characteristic spinal abnormalities, including short pedicles and diminished central spinal canal dimensions (Fig. 8-1), with a cephalocaudal decrease in the coronal interpediculate distance. However, advanced, cross-sectional imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computed tomography [CT]) is necessary to directly identify the classic trefoil central spinal canal morphology and resultant compression of neural elements (Figs. 8-2 and 8-3). Posterior vertebral body scalloping results from vertebral dysplasia and dural ectasia. Platyspondyly is typical, although it may not be remarkable.

|

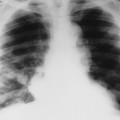

| FIG. 8-1 A 42-year-old female achondroplastic patient with persistent low back pain. A, The bone scan exhibits mild radiotracer uptake secondary to the posterior joint disease (arrow). The T2-weighted, B, sagittal and, C, axial images demonstrate a narrow spinal canal. Achondroplasia is the prototypical example of congenital spinal stenosis. Patients often experience clinical manifestations of spinal stenosis as the congenitally narrowed canal (arrows) is further affected by posterior joint degeneration and disc displacement, which inevitably occur during middle age. |

|

| FIG. 8-2 Achondroplasia in a 5-month-old girl. A, Platyspondyly, posterior scalloping. B, Broad, square ilia, hemispheric capital femoral epiphyses, short femoral necks. C, Exaggerated tibial tubercle apophysis, fibulae overgrowth. (From Taybi H, Lachman RS: Radiology of syndromes, metabolic disorders, and skeletal dysplasias, ed 4, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.) |

|

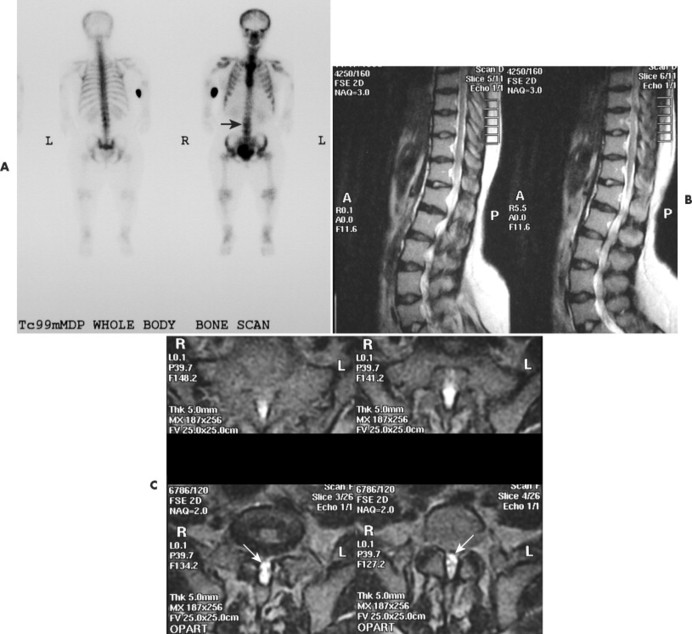

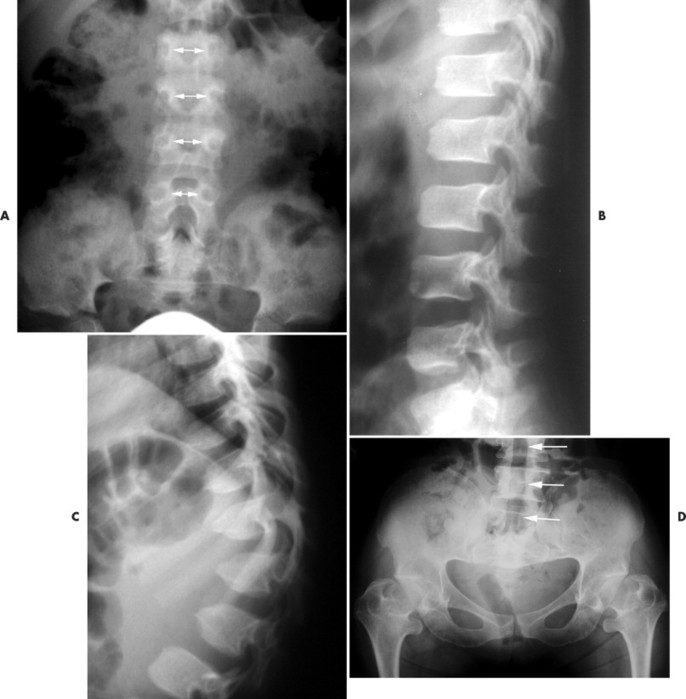

| FIG. 8-3 Achondroplasia. A, Anteroposterior spine shows narrow interpedicular distance in the lower lumbar spine (arrows). B, Lateral lumbar spine. Note the posterior vertebral body scalloping, mild anterior beaking, and short pedicles. C, Lateral spine, more severe dysplasia. Note the thoracolumbar kyphosis with prominent anterior beaking. D, Pelvis in an adult. Note the prior lumbar laminectomy (arrows) performed to relieve spinal stenosis. (From Manaster BJ, Disler DG, May DA: Musculoskeletal imaging, ed 2, St Louis, 2002, Mosby.) |

Degenerative disc disease and facet arthrosis are common in older adult patients because of biomechanical and gross anatomic factors. Degenerative disc and joint disease often is premature and may be unusually severe for age. Vertebral spondylophyte and hypertrophic degenerative facet joint changes may contribute significantly to central canal and nerve root canal stenosis, superimposed on a developmentally small canal dimension. The surgical approach to treatment may range from single-level laminectomy to complete craniospinal decompression from brainstem to cauda equina. This reportedly (and incredibly) does not produce spinal instability. 273

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Achondroplastic dwarfs typically have macrocephaly and a broad, flat nasal bridge. Prominence of the frontal bone and frontal sinuses is described as “frontal bossing.” Achondroplastic adults obviously are short, ranging in height from 112 to 145 cm. However, these are not the shortest of the dwarfs. Patients with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED) or spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia range from 94 to 132 cm and have much more apparent trunk than extremity shortening. 102

Clinically and radiographically apparent angular thoracolumbar kyphosis with a classic “bullet-shaped” vertebra at the thoracolumbar junction is a hallmark of the condition and usually is present at birth. Lumbar hyperlordosis tends to develop in later childhood and into adulthood. 140

As mentioned, achondroplasia is a prototypical cause of developmental spinal canal stenosis, often causing spinal cord, cauda equina, and nerve root compression. Stenosis of the foramen magnum also may lead to brainstem, cerebellar, or upper cervical cord compression, angulation, or displacement in addition to hydrocephalus, which commonly is diagnosed in infancy or early childhood. This may produce neurologic complications, including ataxia, incontinence, and depression of respiratory function, which occasionally is lethal. 191,225,278 Advanced diagnostic imaging has been valuable in identifying infants at risk for these complications and associated abnormalities, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation. 54 Abnormalities on polysomnography, as well as clinical findings of hyperreflexia and clonus, also have been considered to be indications for surgical decompression of the cervicomedullary junction. About 10% of infants fit this clinical picture. Achondroplastic infants should be screened for these findings. 192

Achondroplastic patients often have a waddling gait because of hip joint involvement, frequently leading to advanced osteoarthritis early in life. Femoral epiphyseal changes may resemble those of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

• Achondroplasia is the most common cause of dwarfism.

• A normal or near-normal trunk and marked rhizomelic micromelia are characteristic.

• A number of classic radiographic changes affect the axial and appendicular skeleton.

• Anomalies involving the skull and spine are particularly important because of the potential for neurologic complications.

• Achondroplasia is associated with developmental spinal canal stenosis, often causing spinal cord, cauda equina, and nerve root compression.

• In the peripheral skeleton, in addition to the obvious limb shortening, early, severe, and sometimes debilitating osteoarthritis may develop.

Chondroectodermal Dysplasia

BACKGROUND

Chondroectodermal dysplasia (Ellis-van Creveld syndrome) is an autosomal recessive, short-limbed, dwarfing dysplasia characterized by polydactyly, congenital heart anomalies, and ectodermal dysplasia that are evident at birth. The condition, classified as a short-ribbed polydactyly syndrome (SRPS), is linked to consanguineous relationships. Previously this was particularly common among old-order Amish, but an awareness of this problem has prompted the Amish to encourage young adults to move away and seek a spouse from another Amish community.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Thoracic changes resemble those of Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia. Ribs are short and broad anteriorly, with an increased anteroposterior dimension of the thorax. Constriction of the thorax is caused by diminished coronal dimension. The ilia are hypoplastic. There is variation in shape, size, and number of tubular bones of the hands and feet. Hexadactyly (six digits on each hand and foot) is invariable with this condition and may be associated with syndactyly. There also may be supernumerary carpal bones, carpal coalition across carpal rows, and cone-shaped epiphyses. Congenital radial head dislocation and marked widening of the distal radial and proximal ulnar metaphyses occur, with metaphyseal flaring producing a so-called drumstick appearance.

More generalized alteration of bone formation in the epimetaphyseal region may be seen. Genu varum resulting from a hypoplastic medial tibial plateau may resemble Blount’s disease. Tibiotalar slant and bony excrescences at the medial aspect of the proximal tibia also are commonly seen. The axial skeleton is largely spared, with generally normal skull and spine. 47,166 Coronal vertebral clefts may be seen. 283

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Patients are short, with greater limb shortening distally (acromelic shortening). Skeletal anomalies of size, shape, and number, along with congenital synostoses, may be suspected clinically, but are best assessed radiographically. Nails and teeth are agenetic or markedly dysplastic. Cardiopulmonary complications often lead to death in early childhood, although some individuals survive into adulthood. Dandy-Walker malformation has been reported, but it is unclear whether this is directly related or a coincidental occurrence. 303

• The classic clinical presentation of Ellis-van Creveld disease occurs in infancy or childhood as hexadactyly marked phalangeal and nail hypoplasia, congenital heart anomaly, typical thoracic anomalies, and genu varum.

• Radiologic changes include developmental metaphyseal alterations and congenital synostosis, especially carpal coalition.

Cleidocranial Dysplasia

BACKGROUND

This rather rare, autosomal-dominant condition was first described in 1898, but only fairly recently was localized to the short arm of chromosome 6p, 66,81 refuting an earlier report that the chromosomal abnormality involved was the 8q locus. 32 One third of cases represent new mutations. Despite a name that implies a process limited to the clavicle and calvarium, cleidocranial dysplasia actually is a generalized autosomal dominant dysplasia combining developmental midline spinal defects, delayed skeletal maturity, dental anomalies, and the more widely recognized skull and clavicle abnormalities.

As with most skeletal dysplasias, identification of specific genetic markers has vastly enhanced the ability to distinguish between conditions that share many clinical and radiographic features. This led to identification of newly described dysplasias that otherwise would have been lumped together with another more familiar or common syndrome. 242,296 As a result, it may seem that the study of skeletal dysplasias has advanced from an esoteric and uncertain exercise undertaken by a small, erudite group of pediatric and bone radiologists to a more certain (perhaps still esoteric) exercise carried out by a small (perhaps still erudite) group of geneticists. A report of cleidocranial dysplasia occurring in three consecutive generations, but previously unrecognized in the first two, has prompted recommendation of assessment of family members in every case of what may appear to be a sporadic occurrence of the disorder. 37

IMAGING FINDINGS

Skull.

Cleidocranial dysplasia is characterized by multiple wormian (intrasutural) bones, especially within the lambdoid suture, frontal bossing of the calvarium, and variable hypoplasia and dysplasia of the clavicles (Fig. 8-4). Examination of the development of the cranium in neonates with this condition has revealed a marked delay in skeletal maturity over the first 6 months of life. Also, normal mineralization of the calvarium typically is grossly reduced. Calvarial size may be relatively normal, considering marked postpartum deformity secondary to the poor mineralization. Widening of the skull has been reported in some cases. About 60% of patients have an inverted “pear-shaped” calvarium and a persistent anterior fontanelle, one of the midline defects typical of this disorder. The portion of the skull base formed through enchondral ossification is narrowed and shows delayed ossification. Also apparent is cephalad displacement of the clivus and sella turcica, with anteriorly facing foramen magnum, often accompanied by basilar invagination. The sphenooccipital synchondrosis is widened. 117,119

|

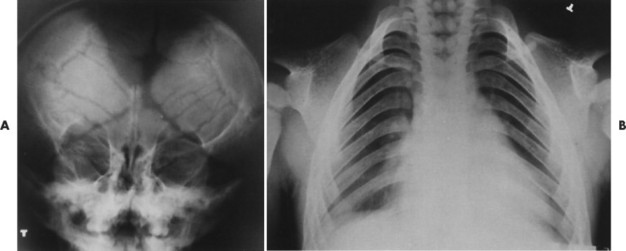

| FIG. 8-4 Cleidocranial dysplasia in a 5-year-old boy with “soft shoulders,” large head, prominent anterior fontanelle open down through forehead, and poor teeth. A, Widely open sutures and fontanelle, and wormian bones. B, Partial aplasia of clavicles, droopy shoulders, small scapulae, spina bifida, wide ribs. (From Taybi H, Lachman RS: Radiology of syndromes, metabolic disorders, and skeletal dysplasias, ed 4, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.) |

Clavicles.

Face and sinuses.

The paranasal sinuses are characteristically absent or hypoplastic, consistent with an abnormality predominating in bones formed, through intramembranous ossification. The sella turcica often is hypoplastic, and the dorsum sellae often is bulbous. Nasal bones almost always are hypoplastic or agenetic. Likewise the zygomatic arches are hypoplastic or absent. 119 All craniofacial regions are affected in cleidocranial dysplasia. 117 Even the hyoid bone may demonstrate decreased ossification. 210 The height and width of the mandible and maxilla are decreased, with anterior inclination of the mandible. 117 The coronoid process of the mandible is slender and obliquely oriented in a posterosuperior direction. Persistence of a midline suture at the mandibular symphysis is classic for cleidocranial dysplasia. 65 Facial abnormalities appear to progress with increasing age and may not be readily apparent in younger children. 119,120

Other anomalies.

Other anomalies include incompletely descended, hypoplastic scapulae with shallow glenoid fossae. The iliac wings are hypoplastic and ossification of the pubic bones and obturator rings is delayed and deficient. Pubic diastasis is a characteristic feature. Coxa vara or valga may occur, with the latter more common. Long bones may be overtubulated (excessively constricted at the diametaphyseal junctions). Fibular agenesis or congenital pseudoarthrosis of the femur may occur.

The predominant finding in the spine is spina bifida occulta, most commonly in the cervicothoracic region. Another potential anomaly is structural scoliosis resulting from vertebral segmentation anomalies, including hemivertebrae and asymmetric nonsegmentation (block vertebrae). The hands may demonstrate hypoplasia of carpal bones and distal phalanges, with relative hyperplasia of the epiphyses, especially of the distal phalanges. 211 The second and fifth metacarpals typically are long, and the second and fifth middle phalanges are short. Supernumerary ossification centers may be apparent.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The clinical manifestations of cleidocranial dysplasia are highly variable. Affected individuals may be somewhat below average in height. The head is macrocephalic overall, but shortened in an anteroposterior dimension (brachycephalic), with frontal bossing and a small face. The shoulders may appear drooped and demonstrate an increased range of motion. Genu valgum and brachydactyly also may be seen. Respiratory dysfunction may result from a developmentally narrow thorax. 211

Unlike other conditions involving midline defects and spinal dysraphism, cleidocranial dysplasia is not classically associated with neurologic deficit. When present, such a deficit should prompt assessment for other abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS), such as neoplasm, syringomyelia, or other developmental anomaly. 58,190 Supernumerary and anomalous teeth are typical in cleidocranial dysplasia. A strategy has been devised to successfully predict the development of supernumerary teeth before the permanent teeth are fully developed. This allows extraction of the supernumerary teeth and, when indicated, of the primary teeth and overlying bone, improving eruption of the remaining permanent teeth. 118,213

• Radiographic finding include wormian bones, clavicular deformity (aplasia [10%] and hypoplasia), mild spinal dysraphism (spina bifida occulta), delayed closure of the symphysis pubis, and supernumerary epiphyses.

• The patient’s clinical appearance is marked by drooping shoulders, possible respiratory distress, large head, small face, and anomalous teeth.

BACKGROUND

Congenital insensitivity to pain is sometimes described as “indifference to pain.” This is somewhat misleading, implying that pain is perceived but ignored. Instead an essential absence of or marked diminution of pain perception exists, whereas all other sensory findings are normal. The condition, first described in 1932, may spare sensation of light touch, and deep tendon reflexes also may be normal.

IMAGING FINDINGS

The radiographic findings of congenital insensitivity to pain are those seen in other neuropathic conditions and summarized as the classic 6 Ds of neuroarthropathy. As one of the classic causes of “degenerative joint disease with a vengeance,” there is typically joint destruction, disorganization, diminished joint space, intraarticular debris (detritus), joint distention, and reactive subchondral sclerosis (increased density). Because of its presence from infancy, congenital insensitivity to pain typically leads to disruption of the physes, essentially representing stress fracture through the growth plate. This may be evident in children with spinal dysraphism as well. Extensive subperiosteal hemorrhage also may occur, along with periarticular disintegration and fragmentation, which may be mistaken for child abuse. 252 In the spine, radiographic changes are similar to those seen in neuroarthropathy (e.g., from syphilis or diabetic neuropathy), which may be thought of as “degenerative disc disease with a vengeance.”198

Patients with congenital insensitivity to pain may have complicating infections of both the soft tissues and skeleton in addition to neuroarthropathy. This results from a chronic open wound resulting from an abrasion, burn, or other superficial injury. 188 Such infections may necessitate amputation. Other complications that may require extensive orthopedic or neurosurgical intervention include pathologic fracture, dislocation, autoamputation, and rapidly progressing scoliosis. 90,99

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Generally, the abnormality is manifested in infancy or early childhood as a marked absence of reaction to pain stimuli, frequently with cutaneous manifestations of scars and burns, unnoticed by the child. Self-mutilation and aggressive behavior may occur, especially in conjunction with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome or familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome). Patients with these and related hereditary sensory neuropathies (HSN) or dysautonomic conditions also may suffer from mental deficits, anhidrosis (inability to sweat), and resultant alteration of thermoregulation. 57,185

A distinct form of congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (CIPA) has been identified, also known as hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type IV. Nearly 20% of patients with this disorder die within the first 3 years of life because of hyperpyrexia. 220 At least five variants of HSN exist; in some cases a precise distinction of one disorder from another may not be possible without prolonged follow-up and nerve biopsy. Reports detail patients who are initially diagnosed with congenital insensitivity to pain, and later determined to have a hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy. 141 Nerve biopsies reveal loss of nonmyelinated and small myelinated fibers. 220

Recently, abnormalities of muscle also have been reported in patients with congenital insensitivity to pain. Muscle weakness and hyporeflexia or areflexia may be evident. Histologically and anatomically, the involved muscle demonstrates marked variation in fiber size. Some small fibers have central nuclei and a few small angulated fibers. 261

• Congenital indifference to pain is suggested by an infant or young child presenting with a history of multiple traumas (e.g., burns, abrasions) that are unnoticed by the patient and, at least initially, also by the parents or guardians.

• Repeated traumas to joints and surrounding structures, resulting from a lack of protective proprioceptive feedback, lead to an appearance of advanced joint disease.

• Developing physes are particularly vulnerable to stress fractures, resulting in significant fragmentation and other architectural distortion.

• A loose periosteum in infants and children and subperiosteal hemorrhage may lead to remarkable periosteal reaction.

• Severe burns may be associated with joint contractures.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

BACKGROUND

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is lateral displacement of the hip with varying degrees of acetabular dysplasia. In the past the condition was termed congenital hip dysplasia or congenital hip dislocation. The newer term reflects the fact that the condition may not be present at birth, but develops in infancy and early childhood. It appears six to nine times more frequently in females, slightly more often on the left, and occasionally bilaterally.

IMAGING FINDINGS

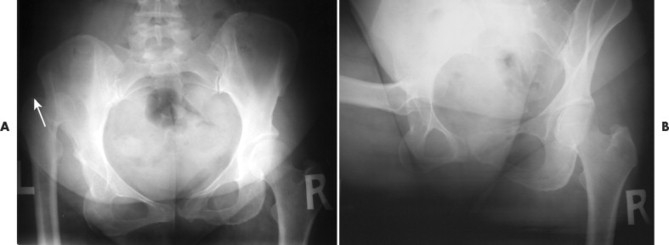

The proximal femur may be subluxated or dislocated. Displacement is difficult to detect on radiographs in neonates and young infants because of the incomplete mineralization of the hip and pelvis. Classic imaging findings are summarized in Putti’s triad, consisting of lateral displacement of the femur, a small or radiographically invisible femoral capital epiphysis, and an increased acetabular angle (FIG. 8-5FIG. 8-6FIG. 8-7 and FIG. 8-8). The anteroposterior projection of the hip is used for radiographic assessment. The frog-leg view is not helpful, because the dislocation reduces during the abduction movement. In addition to Putti’s triad, other radiographic features include acetabular sclerosis, shallow acetabulum, and delayed ossification of the femoral head.

|

| FIG. 8-5 Bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip in a 2-year-old girl. Putti’s triad is present on both sides; the right acetabular angle is enlarged to 38 degrees, the left to 44 degrees. The arrows point to bilateral false acetabulae. The acetabular angles should not exceed standards based on age (e.g., at birth they should measure less than 36 degrees in females and 30 degrees in males; see Chapter 4). (From Silverman FN, Kuhn JP: Caffey’s pediatric x-ray diagnosis: an integrated imaging approach, ed 9, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.) |

|

| FIG. 8-6 A and B, Uncorrected developmental dysplasia of the hip (arrow) in a 41-year-old man. The femoral head has displaced laterally and superiorly, with residual deformity of the acetabulum. (Courtesy Matthew Rich, Clearfield, PA.) |

|

| FIG. 8-7 A and B, Three-month-old infant with a subtle lateral dislocation of the reading right femoral head (arrow). Identifying the lesion is made easier by noticing the disruption of Shenton’s line (drawn along the inferior surface of the superior pubic ramus and internal cortex of the femoral neck). (Courtesy Ian D. McLean, LeClaire, IA.) |

|

| FIG. 8-8 A, Chronic developmental dysplasia of the hip (reading right) in a 43-year-old man noted by a widened joint space and a more vertical slant of the left acetabulum than normal (arrows). B, Adult patient with residual deformity from unresolved bilateral developmental hip dysplasia. C, Advanced degeneration of the reading right hip secondary to unresolved developmental hip dysplasia and associated loss of iliofemoral congruence. (B, Courtesy Robert Rowell, Davenport, IA; C, Courtesy Ian D. McLean, LeClaire, IA.) |

Roentgenometrics are useful to assess the acetabular angle and determine whether lateral or superior displacement of the femur is present. The acetabular center-edge angle and acetabular index are useful in evaluating the acetabular angle. Shenton’s line and the iliofemoral line are helpful to assess for femoral displacement. These roentgenometrics have been presented in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Diagnostic ultrasonography, arthrography, and CT are useful to delineate the anatomy of the hip and acetabulum in this disease. These modalities are particularly useful to locate the position of the acetabular labrum, which affects clinical outcome. The case is more difficult to resolve and often necessitates surgical correction if the labrum inverts during dislocation.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Detection of displacement is accomplished largely through the application of appropriate imaging. Ortolani’s and Barlow’s orthopedic maneuvers are helpful, but there is a substantial false-negative rate. Asymmetry of rotation and apparent shortening of the affected leg may be evident when a patient is 3 months old. A waddling gait is typical.

Management is most effective when the condition is detected early, preferably in the neonatal period. Ultrasound is the technique of choice for assessing the immature hip in a neonate suspected of having developmental dysplasia. Mild cases may be successfully treated by maintaining the hips in a position of flexion and abduction. This may be accomplished by double or triple diapering the infant. In more advanced cases, a Pavlik harness (worn full-time for at least 6 weeks, then part-time for another 6 weeks) is used to maintain hip flexion and abduction.

• Developmental hip dysplasia describes lateral displacement of the proximal femur with related dysplasia of the acetabulum.

• Basic imaging findings are summarized by Putti’s triad: lateral displacement of the femur, small or absent femoral capital epiphysis, and increased acetabular angulation.

• Ultrasonography, arthrography, and computed tomography may be used to demonstrate the position of the acetabular labrum, the location of which affects clinical outcome.

• Management is most effective when the condition is detected early.

Diastrophic Dysplasia

BACKGROUND

This autosomal recessive dwarfing dysplasia derives its name from the twisted appearance of the spine and extremities resulting from scoliosis, which may be progressive, as well as deformities, contractures, subluxations, and dislocations of the extremities. The condition is particularly common in Finland, although the reason is not clear. A study from the University of Helsinki demonstrated ankle and foot anomalies in 93% of cases, with the most common deformity involving combined metatarsus valgus and metatarsus adductus or equinovarus. 226

IMAGING FINDINGS

General.

Radiographic changes are consistent with the dwarfing and diffuse skeletal deformities seen clinically (Fig. 8-9). Severe peripheral deformities typically lead to early, advanced degenerative joint disease, which may necessitate arthroplasty. 193 Tubular bones are markedly shortened and metaphyses are widened, which does not help much in distinguishing this from other dwarfing conditions.

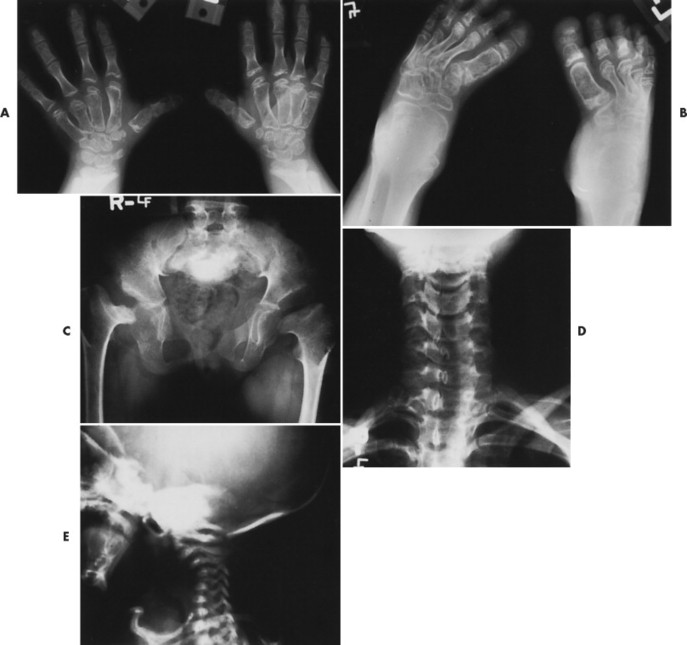

|

| FIG. 8-9 Diastrophic dysplasia. A, Unusually shaped and extra carpal bone in a 6½-year-old child; undermodeled metacarpals; epiphyseal irregularity; hypoplastic, almost ovoid first metacarpal (hitchhiker thumb). B, Unusual clubfoot with twisted metacarpals in a 6½-year-old child. C, Severe femoral epiphyseal hypoplasia in a young adult; coxa vara; sacral posterior clefting. D, Clefting of posterior processes of cervical spine in a young adult. E, Severe cervical kyphosis in a newborn. (From Taybi H, Lachman RS: Radiology of syndromes, metabolic disorders, and skeletal dysplasias, ed 4, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.) |

Hands.

The first metacarpal is characteristically more severely affected and may be oval in shape. The carpal bones may demonstrate multiple accessory ossification centers, premature ossification, and deformity.

Epiphyses.

The appearance of epiphyseal ossification centers is delayed, and other epiphyseal changes, which tend to be most marked at the proximal femora, resemble those of severe Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Developmental joint space narrowing may occur, and equinovarus deformity is common. 211

Spine.

Severe cervical kyphosis resulting from dysplastic vertebrae occurs in about one third of patients and may reach 180 degrees, with the spine literally folded in upon itself. Unlike extremity deformities, which typically increase as the child ages, some of these kyphoses completely resolve by adulthood. Others may lead to myelopathy or even death. 15 Scoliosis occurs in about one third of all patients, but it is more common in female patients (approximately 50%). Although they typically develop at a much younger age than idiopathic scolioses (usually apparent by 2 to 4 years of age), fewer than 15% of these curves progress beyond 50 degrees. 201 Diastrophic dysplasia represents a rare cause of atlantoaxial subluxation. 212 Congenital central spinal canal stenosis often occurs, with a narrowed interpediculate distance, although this is not as marked or consistent as in achondroplasia.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Clubfoot deformity has been reported in the literature frequently, although a true clubfoot (talipes equinovarus) is actually not seen. Hands and feet are short and broad, demonstrating a characteristic abduction or “hitchhiker” deformity of the thumbs and great toes. Peculiar cystic masses develop on the external ears, resulting in clinically apparent deformity. Cleft palate is seen in about 75% of cases, although only about half of these are open and clinically obvious. 214

Expression is variable. Some patients attain a normal life span, and others die in infancy from respiratory complications. A milder form of diastrophic dysplasia has been referred to, probably inappropriately, as “diastrophic variant.”110,137 Conversely, particularly severe cases with cervical spine dislocations and congenital heart anomalies previously were considered by some to represent a unique, lethal form of the condition. 91

• Radiographic features include progressive kyphoscoliosis and narrowed interpediculate distance in the spine, especially in the lumbar region.

• The hands and feet demonstrate supernumerary, delta-shaped epiphyses

• A notable angular deformity of the thumb occurs, described as “hitchhiker’s thumb.”

• Severe kyphoscoliosis is common and may demonstrate remarkable improvement over time.

Down Syndrome

BACKGROUND

Down syndrome was first described in 1959 in individuals with ocular abnormality, dystonia, mental and developmental retardation, brachycephaly, and macroglossia. Although most affected individuals demonstrate 47 chromosomes, this trisomy 21 configuration is absent in 5% to 10% of individuals with the typical phenotype. Such cases exhibit translocation and mosaicism. 289

A well-known relationship exists between advancing maternal age and an increased incidence of trisomy 21. Women more than 35 years of age are typically offered prenatal testing. Maternal serum markers have been used recently, typically to detect unborn babies in the second trimester at risk for Down syndrome. The first of the serum markers to be used was maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP), but unconjugated estriol (uE3) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) have been used as well. None of these is infallible, and there remains some controversy about which is the best method of detection in utero. Combining measurement of MSAFP and free-beta hCG with maternal age reportedly results in an 80% detection rate and a 5% false-positive rate. This still leaves mothers with a 1 in 20 chance of aborting a normal baby in response to a positive test and a 1 in 5 chance of having a baby with Down syndrome despite a negative test. 150

IMAGING FINDINGS

Atlantoaxial instability.

The single most important articulation to evaluate in a patient with Down syndrome is the atlantoaxial articulation, with anterior atlantoaxial dislocation or instability in approximately 20% of affected individuals. 170 The most critical ligamentous structure to assess is the transverse ligament. The most crucial plain film study is a lateral cervical film with head nod or flexion to evaluate for anterior atlantoaxial subluxation or the far less common occipitoatlantal instability. This is essential, especially with patients in whom activity, anticipated therapy (especially spinal manipulation), or past atlantoaxial surgical fusion may place the upper cervical complex or craniovertebral junction at increased risk. 221

The relationship between Down syndrome and congenital laxity of the transverse portion of the cruciate ligament of C1 is well known, and is generally considered to be the primary etiology for most cases of atlantoaxial instability and subluxation. However, other factors such as odontoid hypoplasia and dysplasia along with upper respiratory infections and trauma are believed to contribute. 159,270 The atlantoaxial relationship in Down syndrome does not tend to change significantly over time, at least in asymptomatic individuals. Unless a clinical indication exists, serial lateral and flexion lateral cervical radiographs typically are not warranted. 205

Atlas hypoplasia.

A lesser-known, associated anomaly is a developmentally short posterior arch of C1, seen in more than one fourth of patients in one study. 160 This could present a sort of “double jeopardy” in the presence of atlantoaxial instability. This anomaly is readily detected on lateral cervical radiographs and appears as an anterior displacement of the spinolaminar junction line of C1 relative to that of C2. When anterior atlantoaxial subluxation is present because of abnormality of the transverse ligament, it is difficult to estimate the potential contribution of a short posterior arch to spinal canal stenosis. As mentioned, Down syndrome patients also have an increased incidence of occipitoatlantal hypermobility and instability. Anteroposterior translation of the occiput between the neutral and fully flexed neck posture averages about 0.6 mm in normal individuals. A measurement of more than 1 mm in an adult implies instability. A study of 38 children with Down syndrome demonstrated an average of 2.3 mm, with a range from 0 to 6.4 mm. However, only one of these patients had symptoms that might be attributed to occipitoatlantal instability. The clinical implications are not entirely clear, but caution is indicated and craniovertebral junction instability is possible, even in the presence of an apparently stable atlantoaxial articulation. 162

Cervical spine.

Other abnormalities of the cervical spine identified on plain film radiographs include an unusually high incidence of degenerative joint changes in the mid to upper cervical spine, congenital synostosis, and developmental platyspondyly. A relationship is reported between Down syndrome and small separate ossicles in the upper cervical region, which are thought to represent avulsions of the distal aspect of the dens rather than associated anomalies. 76 Partial or complete hypopneumatization of the sphenoid sinus also may be noted on the lateral cervical neutral view, although typically without clinical relevance. 170,265 Other abnormalities associated with Down syndrome include inconsequential but classic findings, such as a prominent conoid tubercle of the clavicle. 280

Organ systems.

A variety of other anomalies have been reported in individuals with Down syndrome, affecting virtually all organ systems. Plain film radiography may be used to identify infants with duodenal atresia, the most common gastrointestinal anomaly, or thoracic anomalies such as diaphragmatic hernia. Angiography may demonstrate anomaly of the radial, anterior interosseous, ulnar, subclavian, or vertebral artery. 149,209

Other anomalies.

Milder skeletal changes include rib anomalies, especially agenesis of the twelfth ribs, microcephaly with hypopneumatized sinuses, clinodactyly, and brachydactyly. Hypoplasia of the middle phalanx of the fifth digit is seen in about 60% of patients. Characteristics may include a short, arched hard palate, a small posterior fossa, and calcification of the basilar ganglia, best demonstrated on CT. 113,215 Accessory epiphyses and supernumerary ossification centers of the manubrium may be seen in as many as 90% of patients. 46,215 Knee pain and dysfunction should prompt an evaluation for patellofemoral dislocation, present in about 4% to 8% of individuals with Down syndrome, but rarely disabling. 60 Infants with Down syndrome demonstrate flared iliac wings and flat acetabular roofs. In ambulatory adult patients, this may contribute to hip instability and frequently, early, advanced osteoarthritis. 112

SPECIALIZED IMAGING

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have demonstrated a variety of intracranial abnormalities, including abnormally large sylvian fissures, mega cisterna magna, and cerebellar hypoplasia. Hippocampal and neocortical structures are smaller, whereas the parahippocampal gyrus is larger than normal. CT may demonstrate intracranial calcification in as many as 85% of patients, most of which are not directly associated with clinical findings. These calcifications affect the basal ganglia, choroid plexus, and pineal gland. However, some overlap is likely with normal physiologic calcification, because a high percentage of normal individuals demonstrate similar calcifications. 3 It does not appear that these calcifications are related to the increased incidence of seizure disorders in patients with Down syndrome. 254

Older adult Down syndrome patients have greater cerebellar atrophy, related ventricular dilatation, and deep white matter lesions than the normal aging population. Vascular studies demonstrate decreasing cerebral perfusion, presumably related to altered blood–brain barrier permeability. Dynamic MRI shows a fluctuating cortical cerebrospinal (CSF) volume in aging Down syndrome patients similar to otherwise normal elderly individuals with shunted hydrocephalus. This finding, first reported in 1995, suggests a relationship between aging in Down syndrome and edematous states of the brain. 64

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Leukemia.

Leukemia is one of the most serious complications of Down syndrome. About 50% of cases represent acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL). This form typically occurs by age 4, and may be preceded by transient leukemia (TL), involving a megakaryoblastosis, which clears by 3 months of age. Between 20% to 30% of infants with TL develop AMKL. 306 Transient leukemoid reactions, myelofibrosis, and leukemia may all result from an increased sensitivity of cells to interferon in patients with Down syndrome. This results in aberrant antigen expression, which leads to autoimmune disease. In the bone marrow, this may manifest as premature egress of blast cells (as in TL inflammation) or incomplete repair (as in myelofibrosis and binding of autoantibodies to cell nuclei), resulting in malignant transformation and leukemia. 305

Atlantoaxial instability.

As mentioned, atlantoaxial subluxation and instability is a second potentially life-threatening complication commonly encountered. The only clinical finding that may have some predictive value for the presence of this condition in otherwise neurologically intact individuals is gait disturbance, but the sensitivity of this finding was only 50% in 180 children with Down syndrome, with a specificity of 81%. 234 This study failed to identify any reliable clinical indicators of atlantoaxial subluxation or instability and also concluded that x-rays, like clinical indicators, were not reliable for detecting this complication. Other studies have disputed this. Measurement of the anterior atlantodental interspace on neutral and flexion lateral cervical radiographs typically is still performed to identify at-risk individuals. 170,221,265 This includes patients being considered for spinal manipulation, participating in contact sports, and (preoperatively) being anesthetized, especially for otolaryngeal surgery. 97,171

OTHER FINDINGS

In addition to the features in the original report of this syndrome, gastrointestinal anomalies, especially duodenal atresia, are typical. 246 Cardiac anomalies and pulmonary hypertension are frequent, with congenital heart disease found in some 40% to 50% of patients. Atrioventricular and ventriculoseptal defects and tetralogy of Fallot are among the most common, whereas certain other anomalies, including situs inversus and transposition of the great vessels, are distinctly uncommon. 158 In about a dozen reports, Down syndrome has been associated with moyamoya disease, an intracranial vascular anomaly. 14 About 40% of patients have developmental dysplasia of the hips. 142,215 Tracheal, anorectal, and esophageal anomalies also are seen. 271,282 A characteristic form of subpleural cystic pulmonary disease has been reported, which typically is difficult to appreciate on plain films and may require high-resolution CT of the chest. 92

Down syndrome is associated with celiac disease (gluten enteropathy). Because of other common abdominal complaints, considerable delay frequently occurs in diagnosing celiac disease in Down syndrome patients, versus otherwise normal patients. The length of time between initial symptoms and diagnosis averages 2.5 years in Down syndrome patients versus 8 months in non– Down syndrome patients. 104 This condition should be suspected in any child with Down syndrome who shows failure to thrive, especially when accompanied by chronic diarrhea. 104

An increased incidence of a variety of autoimmune diseases occurs in Down syndrome, including thyroid disease. Although hypothyroidism is most common, reports exist of hyperthyroidism in the form of classic Graves disease. 264

In addition to gastrointestinal and autoimmune diseases, males with Down syndrome appear to have an increased risk for testicular cancer. 72

• Down syndrome, or trisomy 21, produces classic clinical features and is typically diagnosed or at least suspected before radiography.

• Plain film radiographs and other diagnostic imaging studies typically are obtained to assess for the multitude of associated anomalies seen in this condition.

• Approximately 20% of Down syndrome patients have instability or dislocation of the atlantoaxial joint.

• These anomalies affect most organ systems, including the gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, and skeleton.

• Potentially life-threatening atlantoaxial subluxation and instability are special concerns even after other serious internal organ system anomalies have been ruled out in the prenatal and neonatal period.

Epiphyseal Dysplasias

The epiphyseal dysplasias represent an overlapping group of diseases that express the common denominator involving growth deformities of the epiphyses. Three systemic and one localized form of epiphyseal dysplasia are presented in this chapter. The three system varieties include chondrodysplasia punctata, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, and spondyloepiphysis dysplasia. Dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica (Trevor disease) is the localized form.

Chondrodysplasia Punctata

BACKGROUND

Chondrodysplasia punctata is a rare familial disorder characterized by punctate or “stippled” calcification of developing epiphyses. As with other dysplasias, chondrodysplasia punctata is actually a heterogeneous group of disorders rather than a single disease entity, with at least four distinct forms reported. 143,253

IMAGING FINDINGS

Radiographs illustrate marked shortening of tubular bones and expanded metaphyses, with marked rhizomelic shortening of long tubular bones (Fig. 8-10). Epiphyseal ossification is delayed and irregular, with characteristic “stippling” bilaterally and symmetrically. This gradually diminishes in infants who survive. Generalized decreased bone density also occurs over time. Similar stippled calcification occurs in the spine and pelvis, as well as in the ribs, laryngeal and tracheal cartilages, tarsal and carpal regions, and patellae.

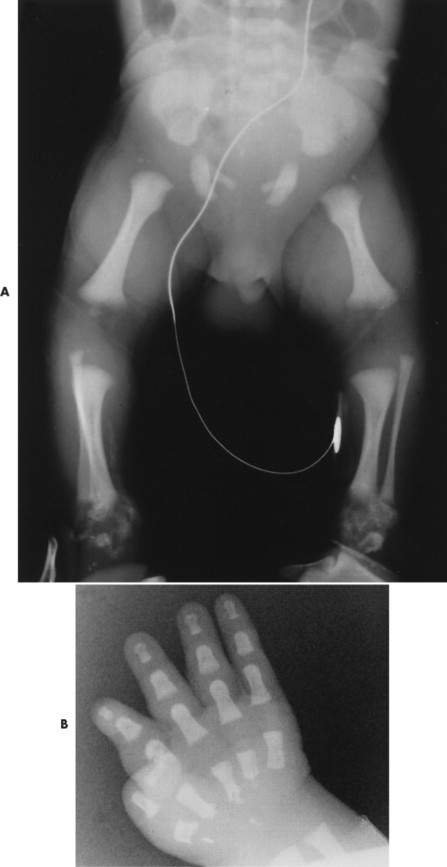

|

|

| FIG. 8-10 Chondrodysplasia punctata, tibial-metacarpal type in the neonate. A, Diffuse areas of stippling in hips, ankles, and sacrum; short femurs, long fibulae with very short tibiae. B, Generalized brachydactyly with special shortening of the first, third, and fourth metacarpals and the proximal phalanx of the second digit combined with stippling in these areas and the carpus. C, Coronal cleft vertebrae and sacrococcygeal stippling. D, Mild upper extremity shortening with epiphyseal area stippling. E, Severe stippling in the tarsal region. (From Taybi H, Lachman RS: Radiology of syndromes, metabolic disorders, and skeletal dysplasias, ed 4, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.) |

Radiographic changes reflect histologic and gross anatomic changes resulting from altered development and alignment of chondrocytes. 85 Poznanski202 has emphasized the fact that the presence of punctate or “stippled” epiphyses merely represents a radiographic sign, as opposed to a specific disease entity. In fact, the differential diagnosis for stippled epiphyses is extensive. The conditions most closely resembling chondrodysplasia punctata, radiographically, are Zellweger syndrome and warfarin or alcohol-related embryopathy. The presence of brain lesions distinguishes Zellweger syndrome from chondrodysplasia punctata. A history of warfarin (Coumadin) treatment or alcoholism in the mother of an affected infant is a red flag for warfarin or alcohol-related embryopathy. 143,202 Evidence exists that warfarin-induced changes may result from the same deficiency of a novel sulfatase enzyme seen in chondrodysplasia punctata. 73

Chondrodysplasia punctata, along with Kniest syndrome, metatropic dwarfism, and some forms of osteopetrosis, may demonstrate a coronal cleft in the vertebral bodies in utero, detectable with ultrasound. Generally this cleft is obliterated before birth. Dysplasia of vertebral bodies may result in kyphoscoliosis or other spinal deformity. Rare manifestations of chondrodysplasia have been reported, including asymmetric or unilateral involvement, which may overlap with the so-called CHILD syndrome, consisting of congenital hemidysplasia, ichthyosiform erythroderma, and limb defects. 96 Reported characteristics include a long bone, cone-shaped phalanges and metacarpal bones, brachydactyly, and bowing of the long bones. 143

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The most readily identifiable form of chondrodysplasia punctata is an autosomal recessive type characterized by rhizomelic shortening of the extremities, microcephaly, a depressed nasal bridge, developmental delays, congenital cataracts, and joint contracture. Clinical features usually are apparent in infancy, and the condition typically is lethal. A milder, autosomal dominant form (Conradi-Hünermann syndrome) demonstrates similar but less severe changes, with patients more often experiencing a normal life span and no significant neurologic deficit. 44,238,241 An X-linked dominant form and a mild sporadic form (Sheffield type) also have been identified. 143,157 In addition to characteristic epiphyseal changes, seen radiographically, ichthyosiform (resembling fish scales) dermatitis exists. 143 There are few other classic clinical features.

• All forms of the disease are rare.

• The classic radiographic feature of “stippled” epiphyses also may be seen in other conditions, such as warfarin or alcohol-induced embryopathy, and therefore are not pathognomonic for this condition.

• Other radiographic findings, including dysplasia of long bones and vertebrae, are variable and nonspecific.

• Clinical findings are not distinctive, with considerable overlap with other conditions.

Multiple Epiphyseal Dysplasia

BACKGROUND

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (MED) is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by dwarfism, brachydactyly, altered appearance, and development of epiphyseal ossification centers, which commonly leads to early, severe osteoarthritis. 189

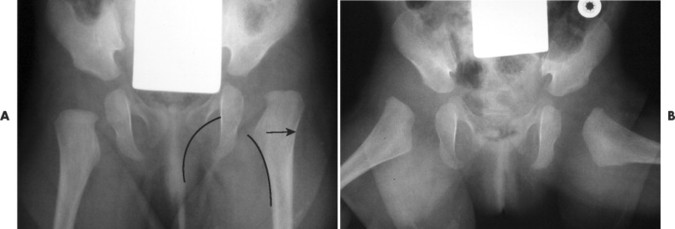

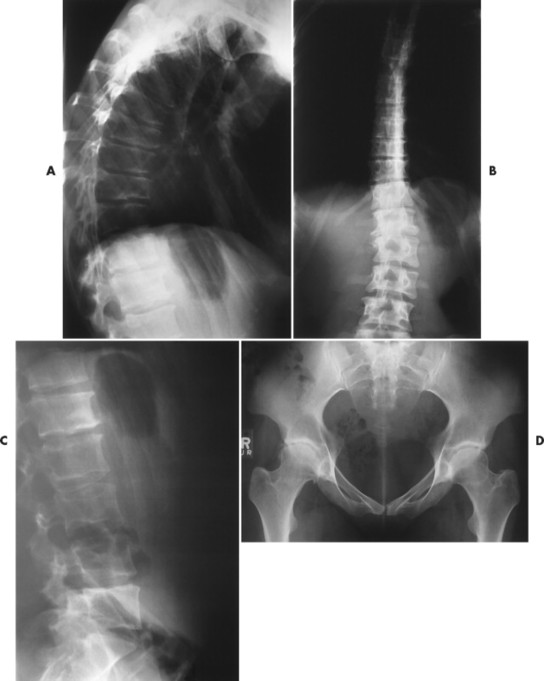

The condition typically is apparent clinically by ages 5 to 14 and may necessitate bilateral total joint arthroplasties by early to middle adulthood (Fig. 8-11). Second only to the hips, other weight-bearing joints and the wrists are the most frequently and severely affected. Unlike spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, the spine usually is normal or only minimally involved (Fig. 8-12).

|

| FIG. 8-11 Classic multiple epiphyseal dysplasia congenita in a 39-year-old woman experiencing severe hip, shoulder, and knee involvement. A, Initial hip films at age 25 years resembled severe bilateral Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease but with more significant acetabular involvement. Note the oversized triangular gonadal shield obscuring the lumbosacral region. B, Osteotomy and instrumentation was performed at age 31, in an attempt to alter weight-bearing stresses on the femoral heads. C and D, The glenoid fossae are markedly hypoplastic and shallow with chronic subluxation of the “hatched head” proximal humeri. E and F, The knees are only mildly affected, with changes resembling osteochondritis dissecans (arrows). Dwarfing has resulted from rhizomelic shortening, most prominent at the humeri. |

|

| FIG. 8-12 A 30-year-old woman with somewhat atypical epiphyseal and spinal dysplasia, diagnosed previously as a form of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (MED) (Fairbank disease). A and B, Unusually marked thoracic spine changes more reminiscent of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED), but with few classic changes in the, C, lumbar and cervical regions. D, Hips and shoulders only mildly affected, with the most apparent changes at the right hip, where moderate, painful osteoarthritis had developed. One might question the diagnosis of MED tarda and suggest the possibility that this represents one of the rare autosomal dominant variants of SED. However, even though by definition the spine is normal with MED, it is not uncommon to see Schmorl’s nodes and irregular vertebral endplates with MED. |

IMAGING FINDINGS

Two distinct subtypes historically have been described based on the degree of abnormality of the developing hips. This classification may assist in prognosis and treatment planning. Both forms are inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder. Type I (Fairbank’s form) is associated with more severe changes, including fragmented and flattened ossification centers and acetabular dysplasia. Markedly deformed femoral heads at skeletal maturity almost invariably lead to premature, severe osteoarthritis. Type II (Ribbing’s form) shows no gross femoral head deformity at skeletal maturity and is less likely to demonstrate severe osteoarthritis. 272

Similarly, a study of shoulders in 50 patients with MED demonstrated two distinct clinical and radiologic subtypes. 115 The first group, with minor epiphyseal changes, developed painful osteoarthritis in middle age but retained shoulder movement until the osteoarthritis was determined to be severe radiographically. The other group demonstrated more severe deformity, described as a “hatchet head” epiphysis. These patients had markedly restricted glenohumeral motion early, but, like the other group, did not experience pain until they were in their forties or fifties. 115

A limited focal epiphyseal dysplasia isolated to the femoral heads is termed dysplasia epiphysealis capitis femoris or Meyer dysplasia. This is bilateral in about 50% of cases and five times more common in male patients. Most cases are symptomatic, but a waddling gait sometimes occurs. Radiographs show a hypoplastic proximal femoral epiphysis, with the delayed appearance of single or multiple ossification centers. This improves with age; the separate ossification centers consolidate and develop a nearly normal appearance by 6 years. The only residual finding is a slightly diminished cephalocaudal dimension to the femoral head. 127

CLINICAL COMMENTS

A patient with MED has normal intelligence. Joint pain and gait disturbance are among the most notable clinical manifestations. The joint involvement leads to osteoarthritis, usually by the second or third generation of life. Patients should avoid contact sports and high-impact activities (e.g., running). Weight control should be emphasized in conservative management. Osteotomies may be done to realign involved joints, and joint replacement surgery is common among adult patients. Urine and blood laboratory indices are within normal limits.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the hip may be superimposed on multiple epiphyseal dysplasias. AVN is suggested by an asymmetric presentation of hip involvement and the presence of metaphyseal subchondral cyst formation.

• Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia is a familial disorder that may show delayed and abnormal appearance and development of the epiphyseal ossification centers, although generally with a normal age of fusion.

• Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia results in short, stubby digits and dwarfing, which is milder than in spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia because of lack of significant spinal involvement.

• Because the end of the bone is altered, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia often results in early, often severe, and disabling osteoarthritis. Changes are most pronounced in the hips and knees.

Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia

BACKGROUND

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED) congenita is an autosomal dominant dwarfing chondrodysplasia that usually is evident at birth and demonstrates a short trunk, generalized platyspondyly, and epiphyseal dysplasia. This has been linked to the gene locus COL2AI for type II collagen production. 2,239 A Danish study of more than 450,000 people demonstrated a prevalence of SED tarda of 7 per million, as compared with 40 per million for MED tarda. 1

The more familiar SED tarda was first described by Maroteaux, Lamy, and Bernhard in 1957 in 20 patients from three families, although reports as early as 1937 described what may have been SED tarda. 125 This is an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by epiphyseal and spinal apophyseal dysplasia, with spinal changes predominating. The condition is usually first suspected in boys 5 to 10 years of age who demonstrate impaired spinal growth. 139 Chest expansion may occur along with typical trunk shortening.

Rare variants of SED tarda have been reported, including a presumably autosomal recessive form occurring in female patients with mild to moderate mental retardation. 133 Another paper reported a case of localized SED apparently affecting only the proximal femora and thoracolumbar junction. This case was discovered, incidentally, in an 11-month-old infant and therefore was classified as SED congenita. 107 One case series from a family with several affected members involved autosomal dominant transmission and, in some instances, hearing deficit. The precise cause for the auditory complication was not indicated. 228 In another family, five patients in three generations demonstrated autosomal dominant SED tarda, associated with congenital hypotrichosis. 284

In 1990 a report of a new form of SED tarda was published. This probably autosomal dominant condition, termed spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia of Maroteaux, demonstrated generalized platyspondyly as in Morquio’s syndrome but without anterior vertebral body beaks. Also unlike Morquio’s syndrome, no increase was noted in excretion of keratosulfate or corneal opacities. Patients were of normal intelligence and skeletal changes were not apparent at birth, which are features shared with Morquio’s syndrome. 56 An interesting variant of SED has been reported in 19 white South Africans of German descent, with mild to moderate dysplasia, progressive infantile kyphoscoliosis, altered trabecular pattern, and generalized joint laxity. 134

Spinal changes predominate in the lumbar region but may affect the entire spine. Characteristics include generalized endplate irregularity and platyspondyly, which may resemble changes of severe Scheuermann’s disease. A characteristic “heaped up” appearance of the vertebral “endplates,” especially superiorly, helps to distinguish SED tarda from other conditions, although a similar appearance may infrequently result from isolated Schmorl’s node formation.

Degenerative disc space narrowing is asymmetric, affecting the posterior aspect of the disc to a greater extent and sometimes leading to false impression of a widened anterior disc space. In the pelvis, the innominate and femoral neck may be hypoplastic. The epiphyses of the larger joints (shoulders and hips) may be slightly flattened, and early, advanced osteoarthritis, especially of the hips, may occur. 134,135,200 The epiphyseal changes are much milder and the spinal changes considerably more pronounced than in MED.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

In addition to a short trunk, generalized platyspondyly, and epiphyseal dysplasia, patients with SED congenita demonstrate other clinical findings, including myopia, hypertelorism, frequent retinal detachment, short neck, mild thoracic kyphoscoliosis, and an expanded anteroposterior thoracic dimension. One case, involving a dysplastic and unstable cervical spine, required surgical management. 144

Individuals affected with the tarda form of SED often complain of back and hip pain, especially in early adulthood. Early advanced degenerative disc disease begins in later adolescence and may be severe by 25 to 30 years of age.

A case series involving three boys with SED tarda and growth failure suggested an association with the nephrotic syndrome. Two of those patients showed focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis on renal biopsy. 62 Another report has appeared of three siblings with an autosomal recessive form of SED tarda, leading to severe, progressive arthropathy, mimicking juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. 216

• With some rather isolated exceptions, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia may be seen as an autosomal recessive (spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita) form or as an autosomal dominant (spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia tarda) form, the latter being more common.

• Generalized platyspondyly with endplate irregularities and classic “heaped up” endplates is expected and is associated with significant short-trunk dwarfism.

• Epiphyseal regions are more mildly affected, especially when compared with multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

Dysplasia Epiphysealis Hemimelica

Also known as Trevor disease, dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica is a rare congenital disorder marked by localized cartilage overgrowth causing asymmetric limb deformity. The condition usually is of the lower extremities, especially the medial aspect of the ankle (e.g., distal tibia, talus, tarsal navicular, and first cuneiform), but the proximal femur, wrist, and foot are other demonstrated locations. The cartilage overgrowth closely mimics osteochondroma. It affects male patients more often than female patients. The condition causes a lump, swelling, and painful joint. There also may be a limp, leg-length discrepancy, and muscle wasting. Surgical treatment often is applied to remove the lesion and reshape the deformed bone.

Homocystinuria

BACKGROUND

Homocystinuria is actually a group of three related genetic abnormalities that result in a deficiency of cystathionine synthetase, the enzyme that metabolizes methionine. The autosomal recessive condition was first described in the early 1960s as a variant of Marfan’s syndrome and is most common in individuals of northern European descent. 35,83,84,168,245

According to common belief, homocystinuria results in abnormal aldehyde cross-linkages and defective collagen synthesis, similar to the pathogenesis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Therefore it should be no surprise that these conditions share features, especially radiographically. However, homocystinuria actually has been classified with alkaptonuria (ochronosis), Menkes syndrome, and pseudoxanthoma elasticum because it secondarily affects the fibrous components of connective tissues. 123,167

IMAGING FINDINGS

Osteopenia.

The imaging findings in homocystinuria may be nonspecific and are not present at birth. Osteopenia is typical and is believed to result from deficiency of collagen cross-linking rather than a gross deficiency in collagen itself. 152 The presence of osteoporosis, often with multiple compression fractures, helps to distinguish homocystinuria from Marfan’s syndrome.

Skeleton.

Skeletal abnormalities occur in up to 60% of patients and closely resemble those of Marfan’s syndrome. Extremities are long and thin, and patients are usually above average in height. Arachnodactyly typically is seen. Multiple growth resumption lines may be present. Scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and generalized joint laxity may appear to be identical to Marfan’s syndrome. Joint contractures may occur in the knees, elbows, and digits, whereas such contractures are usually limited to the fifth digits in Marfan’s syndrome. Ligamentous laxity may result in genu valgum, patella alta, and repeated subluxations. Infants and children may demonstrate metaphyseal flaring and irregularity of epiphyseal ossification centers.

Other reports include a variety of other less common or less classic imaging findings diffusely affecting the skeleton, in addition to vascular calcification and medullary sponge kidney. 28,31,45,168

Skull and facial changes in homocystinuria include sinus expansion, a widened diploic space, prognathism, and dural calcification. 168,245 The spine may show early advanced degenerative disc disease, and posterior vertebral body scalloping. This appears to be a primary developmental abnormality rather than a pressure-related change, as from dural ectasia. 28,245

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Homocystinuria is generally asymptomatic in infants and very young children, although urinary levels of homocystine are increased. Skin lesions begin to develop, including a malar flush, striae over the extremities and buttocks, and scars described as having the appearance of “cigarette paper.” The palate is high and arched, and dentition is poor. Hair usually is thin and sparse. 168

Homocystinuria primarily affects the CNS, eyes, skeleton, and cardiovascular system. Increased homocystine levels are strongly correlated to atherosclerotic, coronary artery, and thromboembolic disease. Cardiopulmonary diseases are the most common causes of death. 49 Cystic medial necrosis occurs, as in Marfan’s syndrome, but aortic dissection, a common cause of premature death in Marfan’s syndrome, generally is not seen in homocystinuria. Accumulation of homocystine may adversely affect platelets, clotting factors, and vascular endothelial cells.

It is believed that individuals with deficiencies of vitamin B6, B12, or folic acid or who are heterozygous for cystathionine synthetase deficiency are at increased risk for occlusive vascular disease and that supplementation may lower the plasma homocystine levels in some affected individuals. 31,163,217 Diets low in methionine and supplementation with betaine or its precursor choline may be beneficial in management of homocystinuria. 248,287 Decision making, especially when considering elective surgery, must reflect the fact that surgeries increase the risk for vascular catastrophes. 28

The most characteristic ocular lesion is dislocation of the lens, which also is seen in Marfan’s syndrome. Lens dislocation may be detected in infancy in homocystinuria, but not in Marfan’s syndrome. 28 Other optic anomalies also may occur, including congenital cataracts and glaucoma.

Unlike Marfan’s syndrome, CNS involvement leading to mental deficit and seizures is seen in about 30% of patients, although the pathogenesis has not been delineated clearly. CNS complications may be modified by therapy. 245

• Homocystine and methionine accumulate in the tissues as a result of an autosomal recessive deficiency of cystathionine synthetase.

• The accumulation of homocystine and methionine leads to mental deficit in 60% of patients and marfanoid features, including tall, thin stature, and arachnodactyly, as well as scoliosis, pectus excavatum or carinatum, and genu valgum.

• Vascular changes are similar to those of Marfan’s syndrome, with medial degeneration of arteries.

• Lens subluxation, common to both conditions, typically occurs inferiorly in homocystinuria and superiorly in Marfan’s syndrome.

• Osteoporosis is a distinctive feature of homocystinuria, as is the presence of flared metaphyses and diffuse joint contractures.

Klippel-Feil Syndrome

BACKGROUND

As with so many other syndromes bearing the name of long-dead scholars who cannot defend or explain themselves, the Klippel-Feil syndrome gradually has evolved from a concise clinical triad to a confusing collection of loosely related vertebral anomalies. Purists may still apply the eponym only to the triad first described in 1912 by Klippel and Feil, without benefit of radiographs. They described patients with a short neck (often webbed at its base), low hairline, and restricted cervical range of motion, although these features were not carefully quantified. They also described anomalies of the skull base and thoracic cage, which have received little attention over the years. 131,132 Subsequently it was discovered that such patients typically demonstrate vertebral segmentation anomalies, primarily in the form of congenital nonsegmentation (“block vertebrae”).

Today whether proper or improper, the term has been extended to include any patient with nonsegmentation of even a single vertebral motion unit, although it is most often implied to mean at least two vertebral motion units. In the context of this broadened definition, approximately 50% of individuals with the requisite segmentation anomalies demonstrate the complete clinical triad. A diagnosis that once was dictated by clinical findings is now made primarily on the basis of radiographic changes in the majority of cases.

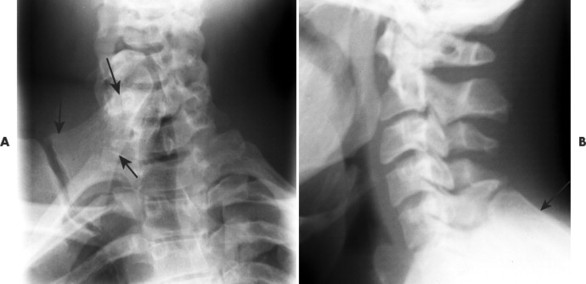

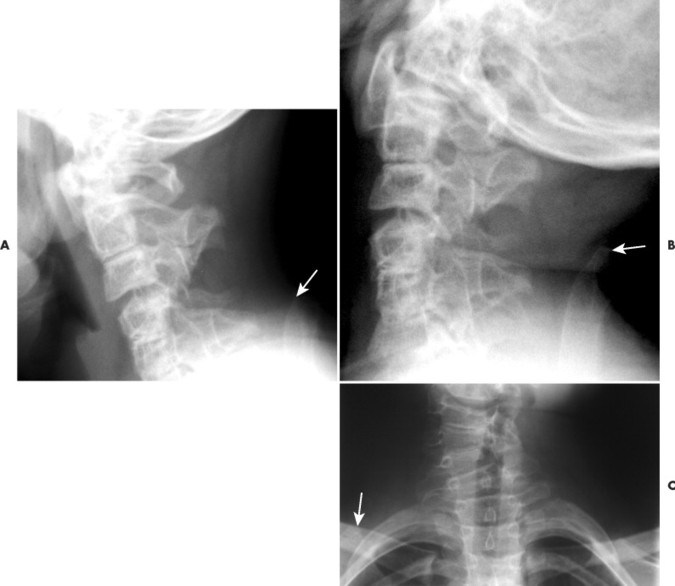

IMAGING FINDINGS

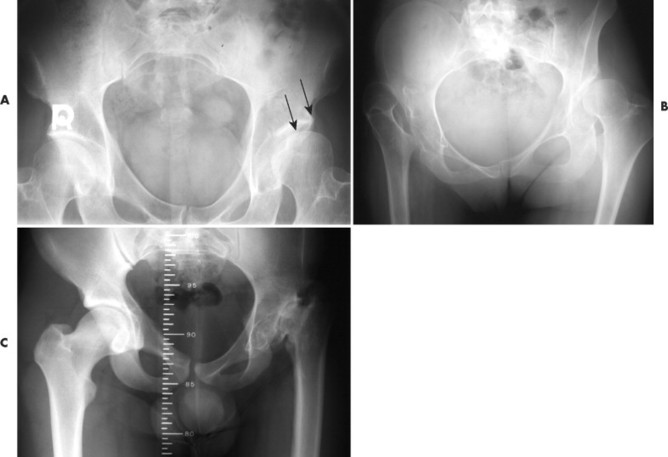

Congenital nonsegmentation most commonly affects C2-3. About two thirds of cases involving C2-3 nonsegmentation also involve assimilation of C1 to occiput (“occipitalization” of C1). Nonsegmentation varies from minimal to extensive and may be continuous or intermittent, with intervening normal disc levels (FIG. 8-13FIG. 8-14FIG. 8-15FIG. 8-16FIG. 8-17FIG. 8-18 and FIG. 8-19). The anomaly may extend caudally to the mid to upper thoracic spine, and may involve similar nonsegmentation in the lower thoracic and lumbar regions. Incomplete or abbreviated forms of congenital nonsegmentation may occur at some levels. Associated anomalies may exist, especially spina bifida occulta and hemivertebrae, which are seen in about 20% of cases and may be associated with structural scoliosis and kyphosis. Intraspinal anomalies such as syringomyelia and diastematomyelia may occur. 78

|

| FIG. 8-13 Klippel-Feil syndrome. Note the congenital nonsegmentation and dysplasia of C2 through C4 and C5-6, with only two functional disc spaces in the cervical spine. Assimilation of the C1 posterior arch to occiput and marked hypoplasia of the dens also are noted. The neck appears to be short, which is more obvious clinically, along with a low hairline and diminished range of motion. Similar vertebral segmentation anomalies also may be seen as an isolated finding or in other syndromes, including neurofibromatosis. |

|

| FIG. 8-14 Klippel-Feil syndrome in a young female patient marked by congenital nonunion defect extending from C5 to T1. |

|

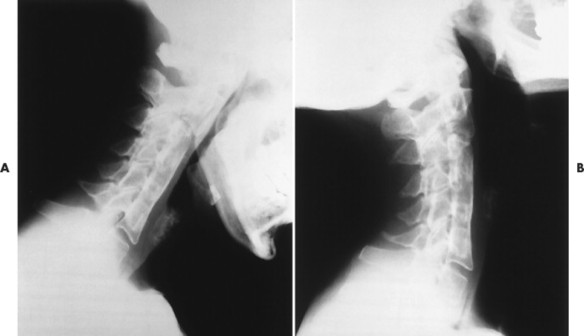

| FIG. 8-15 A and B, Extensive congenital nonsegmentation of C3 through C6. The more normal C2-3 and C6-7 motion units at the cephalic and caudal ends of the nonsegmentation are prone to hypermobility or instability and subsequent premature degenerative disc disease and facet arthrosis. Notice that the range of cervical motion is reduced in this flexion and extension series. |

|

| FIG. 8-16 Sprengel’s deformity. A, Anteroposterior projection illustrates a large bar of bone extending from the medial border of the scapula to the spinous process of C5 (arrows). The articulation with the spinous process is also noted on, B, the lateral projection (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 8-17 Klippel-Feil syndrome presenting as a long block segment extending across two motion units (C4 to C6) in this 51-year-old man. |

|

| FIG. 8-18 Multiple block segments (C2-3 and C5-6), defining Klippel-Feil syndrome, appearing in a 52-year-old woman. Approximately half of patients who demonstrate multiple block segments express the associated clinical triad of a low hairline, webbed neck, and limited range of cervical motion. (Courtesy Nicole Poirier, Shelby Twp, MI.) |

|

| FIG. 8-19 Klippel-Feil syndrome. A and B, Flexion and extension lateral cervical projections exhibit reduced range of sagittal plane motion secondary to the congenital block segments at C2-3 and C4-6. The reading left scapula is slightly elevated on the anteroposterior view (arrows), suggesting, C, a mild expression of Sprengel’s deformity that is also seen on the lateral projections (arrows). |

Other skeletal anomalies commonly accompany the vertebral segmentation anomalies. Failure of descent (often improperly described as “elevation”) of one or both scapulae is seen in about 25% of cases, described as Sprengel’s deformity (see Fig. 8-16). This is more common in patients with extensive spine and, especially, upper cervical involvement and may be corrected surgically. 36,181 Between 30% and 40% of Sprengel’s deformity cases are associated with an omovertebral “bone,” an osseous, fibrous, or cartilaginous structure extending from the scapula (omo-, meaning “scapula”) to the posterior vertebral elements, most often in the mid- to lower-cervical region. Solid fusion or an accessory articulation may exist at both the scapular and vertebral junctions. 181 Similar bones have been reported, extending from the upper ribs or clavicles to the vertebrae, although these are rare. 88 Cervical ribs, Srb’s anomaly, and a variety of rib anomalies, including agenesis or synostosis, are common in Klippel-Feil syndrome.

Craniovertebral junction anomalies may be seen in Klippel-Feil syndrome. Basilar impression is common, with or without assimilation of C1 to occiput. Diagnosis of basilar impression is based upon observance of the tip of the dens projecting significantly above McGregor’s line on a well-positioned lateral skull or lateral cervical neutral view. Arnold-Chiari type I malformation also may occur, in which the cerebellar tonsils project significantly below the foramen magnum, extending into the upper cervical canal. Dens anomalies also may be seen. Imaging of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis may be ordered based upon clinical findings and may demonstrate cardiac anomalies (especially septal defects), enteric cysts, accessory lobes of the lung, and anomalies of the urinary tract. 101

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Klippel-Feil syndrome affects males and females equally. The prevalence of congenital nonsegmentation of at least one spinal motion segment has been estimated to be as high as 0.5% in the general population. 236 The segmentation defects in Klippel-Feil syndrome tend to be more extensive and may be associated with neurologic deficit, most often seen with marked upper cervical and craniovertebral junction anomalies. However, many patients are relatively asymptomatic. Cosmetic concerns, including associated spinal curvatures, Sprengel’s deformity, or pterygium colli (webbed neck) may first prompt the patient to seek attention.

Lateral flexion and rotation motion are most markedly restricted, with lesser decrease in sagittal plane rotation (flexion-extension). The head may appear to be resting on the shoulders. Patients may present with acute torticollis. Other signs and symptoms range from neck pain to paresis and paralysis. Hyperreflexia and pathologic reflexes may occur, such as upward-going toes on Babinski testing, signifying an upper motor neuron lesion. Neurologic deficit may be gradual in onset or may appear acutely, often secondary to trivial trauma. Cranial nerve dysfunction also may occur, including oculomotor disturbance. Some patients demonstrate cardiopulmonary, gastroenteric, or genitourinary tract anomalies.

• Klippel-Feil syndrome is most often defined as the presence of multiple block segments, usually in the cervical spine.

• Approximately 50% of Klippel-Feil patients exhibit a classic clinical triad of a short neck, low hairline, and diminished cervical range of motion.

• Additional anomalies of other organ systems occur, often affecting the genitourinary tract. These are often occult on plain films.

• A wide variety of other clinically or radiographically apparent findings have been described in this heterogeneous syndrome.

Marfan’s Syndrome

BACKGROUND

Marfan’s syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder of connective tissues primarily affecting the ocular, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems. As many as 30% of cases may result from sporadic mutations. The condition bears the name of Antonin Marfan’s, who first described the phenotype in 1896. Marfan’s syndrome is estimated to affect 4 to 6 people per 100,000. 154,304 At one time or another, several famous characters from history were thought to have had Marfan’s syndrome, including Niccolo Paganini, Rachmaninov, and Mary, Queen of Scots. 33,156,298 Despite significant investigation and impressive advances in understanding this condition, Marfan’s syndrome remains an enigma in many ways. Numerous questions have gone unanswered about the precise etiology of the ligamentous laxity, muscular hypotonia, and skeletal changes that characterize this disorder. 154