8 Suprahyoid Neck

The neck is the transitional area between the skull base superiorly and the thoracic inlet inferiorly that joins the head to the trunk and limbs. It serves as a major conduit for muscles, vessels, nerves, spinal cord, and spine. In addition, the cervical viscera with unique functions are located here: the larynx and trachea, the pharynx and esophagus, and the thyroid and parathyroid glands.

Structures in the neck are surrounded by a layer of subcutaneous tissue (superficial fascia) and are compartmentalized by three layers of the deep cervical fascia. The facial attachments to the hyoid bone functionally cleave the neck into the suprahyoid neck, extending longitudinally from the skull base to the hyoid bone, and the infrahyoid neck, extending from the hyoid bone to the thoracic inlet.

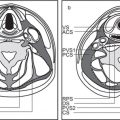

The suprahyoid neck represents the deep core tissues posterior to the sinonasal and oral cavity areas. It contains 12 distinct spaces defined by the layers of the deep cervical fascia (Fig. 8.1). The pharyngeal mucosal, retropharyngeal, danger, and perivertebral are midline nonpaired spaces. The parapharyngeal, masticator, parotid, and carotid are lateral paired spaces. The main characteristic of most of these spaces is their verticality. The carotid, retropharyngeal, danger, and perivertebral spaces extend across both the suprahyoid and the infrahyoid neck. The oral cavity is considered a unique region of the suprahyoid neck because the spaces of the oral cavity—the sublingual and submandibular spaces—do not display the same craniocaudal extent seen in the deep fascial spaces.

A main drawback of computed tomography (CT) imaging is its lack of specificity. By knowing the location and contents of each space, pathology (masses) may be identified and a differential diagnosis developed. Density helps to narrow the list of potential diagnosis of a given mass.

The pharyngeal mucosal space (PMS) is the area of the nasopharynx and oropharynx with the surface structures on the airway side of the middle layer of deep cervical fascia (buccopharyngeal fascia). Cranially, it butts a broad area of the sphenoid and occipital bones. The foramen lacerum is within the abutment area. The level of the glossoepiglottic and pharyngoepiglottic folds of the hypopharynx defines the caudal margin. Posterior to the pharyngeal mucosal space is the retropharyngeal space; bilateral to the pharyngeal mucosal space are the parapharyngeal spaces. The ventral airway side of the pharyngeal mucosal space has no fascial border. Critical contents of the pharyngeal mucosal space are the mucosa, lymphoid tissue of Waldeyer ring (adenoids and faucial and lingual tonsils), minor salivary glands, superior and middle constrictor muscles, salpingopharyngeus muscle, pharyngobasilar fascia (a tough aponeurosis that connects the superior constrictor muscle to the skull base), levator palatini muscle, and the cartilaginous end of the eustachian tube.

A generic pharyngeal mucosal space mass projects into the airway, disrupts the normal PMS mucosal and submucosal architecture, is centered medial to the laterally displaced parapharyngeal space, and invades the parapharyngeal space from medially to laterally. The most common lesion primary to the pharyngeal mucosal space is squamous cell carcinoma.

The parapharyngeal space (PPS) is the central space on each side of the core tissues of the deep face; it extends from the skull base to the level of the hyoid bone. It is symmetrical and situated between layers of the deep cervical fascia, with the pharyngeal mucosal space medial, the parotid space lateral, the masticator space anterior, and the carotid space and retropharyngeal space posterior. Inferiorly, at the pterygomandibular gap, the PPS is not separated from the posterior aspect of the submandibular space by fascia. The PPS contains mainly fat and connective tissue, small branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve [CN] V3), the external carotid artery branches (internal maxillary artery and ascending pharyngeal artery) and pharyngeal venous plexus, lymph nodes, and the rest of the minor salivary gland tissue.

A mass lesion of the PPS is centered within the fat of the space. It may displace the lateral wall of the pharyngeal mucosal space medially, the deep lobe of the parotid gland laterally, and the contents of the carotid space posteriorly. Masses of the surrounding spaces may displace the PPS in a characteristic fashion: a pharyngeal mucosal space mass pushes it from medial to lateral, a masticator space mass from anterior to posterior, a parotid space mass from lateral to medial, a carotid space mass from posterior to anterior, and a lateral retropharyngeal space mass from posteromedial to anterolateral. Usually the PPS serves as an “elevator shaft” through which infection and tumor originating from adjacent spaces may travel. Primary PPS masses (salivary gland tumors, neurogenic tumors, paragangliomas) are unusual.

The posterior cervical space (PCS) is a three-dimensional fascially defined space posteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and anteromedial to the trapezius muscle but superficial to the perivertebral space, largely corresponding to the posterior triangle of the neck seen on clinical examination. The PCS extends from a small superior component near the mastoid tip to a broader base at the level of the clavicle and is bordered superficially by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, medially by the layer of the deep cervical fascia, and ventral by the carotid sheath. The majority of the posterior cervical space is below the hyoid bone. It contains fat, as well as the spinal accessory nerve, spinal accessory lymph node chain, preaxillary brachial plexus, dorsal scapular nerve, and sequestrations of primitive embryonic lymph sacs.

A mass lesion of the PCS is centered within the fat of the space. It may displace the carotid space anteromedially and the sternocleidomastoid muscle anterolaterally and flattens deeper prevertebral and paraspinal structures. The most common lesions of the PCS are reactive and suppurative lymph nodes, malignant nodal metastases, and lymphatic malformations.

The retropharyngeal space (RPS) is a midline space located just posterior to the pharynx. It is delimited anteriorly by the visceral fascia, laterally by the carotid sheath, and posteriorly by the prevertebral fascia. There is a very thin fascial layer of the prevertebral fascia (alar fascia) that divides the RPS into anterior and posterior compartments. The anterior compartment, the “true” RPS, extends from the skull base approximately to the third thoracic vertebral level in the mediastinum, where the alar fascia fuses with the visceral fascia. The posterior compartment, referred to as the danger space, extends from the skull base to the diaphragms and provides a direct pathway for head and neck infections to spread into the posterior mediastinum. In the suprahyoid neck, the RPS contains fat and retropharyngeal lymph nodes, which are divided into lateral (nodes of Rouviere) and medial groups. Both may extend from the skull base to C3. The danger space and the infrahyoid RPS contain only fat. Although separately defined fascial spaces, the RPS and danger space are considered together, because diseases affecting these spaces cannot be differentiated radiologically. A nodal mass of the suprahyoid RPS is centered posteromedial to the PPS, anterior to the prevertebral muscles, and directly medial to the carotid space. The nodal mass displaces the PPS fat anterolaterally and pushes the carotid space laterally (nodal pattern). An extranodal RPS mass, suprahyoidal or infrahyoidal, appears rectangular-shaped or oval, spans the RPS from side to side, and displaces the paired carotid spaces laterally and the pharyngeal mucosal space or visceral space anteriorly, while flattening the prevertebral space muscles posteriorly (nonnodal pattern).

The perivertebral space (PVS) is the cylindrical space surrounding the vertebral column, bordered by the tenacious deep layer of the deep cervical fascia. The attachment of the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia to the transverse process of the vertebral body divides the PVS into the anterior prevertebral portion and the posterior paraspinal portion. The PVS extends from the skull base across the neck to approximately the level of T4 in the posterior mediastinum. The prevertebral portion of the suprahyoid PVS sits directly behind the RPS. Anterolateral to the prevertebral portion of the PVS is the carotid space. The paired posterior cervical spaces are directly lateral to the prevertebral and paraspinal portions of the PVS. The prevertebral portion of the PVS contains the prevertebral muscles, scalene muscles, brachial plexus, phrenic nerve, vertebral artery and vein, vertebral body, and cervical disc. The paraspinal portion of the PVS contains paraspinal muscles, fat, and posterior elements of the vertebral body.

A mass lesion of the prevertebral portion of the PVS is centered within the prevertebral muscles or corpus of the vertebral body and elevates the prevertebral muscles, pushing the danger space/RPS anteriorly. A mass lesion of the paraspinal portion of the PVS is centered within the paraspinal musculature or the posterior elements of the vertebral body, pushing the PCS fat away from the posterior elements of the spine. The PVS is susceptible to inflammatory and infectious processes, as well as neoplasms.

The carotid space is a paired, tubular space encircled by the carotid sheath and composed by slips of all three layers of deep cervical fascia. The carotid space extends from the jugular foramen–carotid canal of the skull base to the aortic arch below. In the suprahyoid neck, the carotid space is bordered anteriorly by the PPS and the styloid process, laterally by the parotid space and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and medially by the RPS. Its suprahyoidal contents include the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and CN IX to XII. The sympathetic plexus is embedded in the medial sheath walls (between the medial carotid space and the lateral RPS). The internal jugular nodal chain is closely associated but not in the carotid space.

A mass may be localized to the carotid space if it is centered within the area of the carotid artery and jugular vein, posterior to the PPS. A mass in the suprahyoid carotid space displaces PPS fat anteriorly and pushes the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and parotid space laterally. As a mass enlarges in the posterior suprahyoid carotid space, it pushes the internal carotid artery anteriorly. A carotid body paraganglioma may splay the external and internal carotid artery.

The masticator space is a large paired space anterolateral to the PPS, dorsal to the buccal space, anterior to the parotid space, deep to the zygomatic arch, and superficial to the pterygomaxillary fissure. It has a broad abutment with the skull base (sphenoid and temporal bones). Splitting of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia forms the masticator space. The lateral slip of the fascia with its origin from the inferior surface of the mandible runs up the lateral surface of the masseter muscle to attach to the zygomatic arch, then continues upward on the surface of the temporal muscle to attach high on the parietal calvarium (suprazygomatic masticator space). The medial slip of the fascia runs up the medial pterygoid muscle to insert on the skull base just medial to the foramen ovale (nasopharyngeal masticator space). The masticator space contains the medial and lateral pterygoid, temporalis, and masseter muscles, the mandibular nerve with two motor branches (the masticator and mylohyoid nerves) and sensory branches (lingual and inferior alveolar nerves), pterygoid venous plexus, inferior alveolar vein and artery, maxillary artery, temporomandibular joint, condylar and coronoid processes, ramus, and posterior body of the mandible.

A mass lesion of the masticator space is centered within the muscles of mastication or the mandible, displaces the parapharyngeal fat posteriorly, or invades the PPS from anterior to posterior. Malignant tumor of the masticator space and infection preferentially spread cephalad toward the skull base, within the muscles of the masticator space or perineurally, may pass through the skull base foramen, and can access the intracranial compartment (cavernous sinus).

The buccal space is bordered medially by the buccinator muscle and the outer cortex of the maxillary alveolar ridge, posteri-orly by the masticator space, laterally by the parotid space, and anteriorly by the superficial muscles of facial expression (greater and lesser zygomaticus muscles and risorius) and the investing fascia. It does not have complete fascial coverings. Superiorly, the buccal fat blends imperceptibly into the fat of the temporal fossa. Inferiorly, there is no true boundary between the buccal space and the submandibular space. Posteriorly, there is often a direct communication between the medial buccal fat and the fat within the masticator space. The buccal space is composed primarily of adipose tissue. The other contents of the buccal space are the buccinator muscle, accessory parotid gland and minor salivary gland tissue, parotid duct, buccal lymph nodes, facial vein, facial and buccal artery, buccal branch of the facial nerve (CN VII), and buccal division of the mandibular nerve (CN V3). The facial artery and vein lie just anterior to the buccal segment of the parotid duct, separating the buccal space into anterior and posterior compartments.

A mass lesion of the buccal space is centered within the fat of the space, adjacent to the outer surface of the buccinator muscle. It may displace the parotid duct posteriorly. Minor salivary gland tumors are the most common of primary buccal space masses, followed by venous malformations.

The parotid space is a paired lateral suprahyoid neck space, completely enclosed by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. It is located posterolateral to the masticator space, posteriorly to the ramus of the mandible, extending from the external auditory canal above to the level of the mandibular angle below. The medial margin of the parotid space abuts the PPS. The posterior margin of the space relates to the carotid sheath vessels, the styloid process, and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The parotid space consists of the gland parenchyma, external carotid artery, retromandibular vein, extracranial facial nerve, intraparotid lymph nodes (~20), and parotid duct. The plane of the facial nerve, lateral to the retromandibular vein, divides the gland into a large superficial (about two thirds of the parotid space) and a deep lobe. The parotid tail is the most inferior aspect of the superficial lobe (inferior 2 cm of the gland). The parotid tail area is located deep and medial to the platysma, anterolateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and postero-lateral to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, projecting into the posterior aspect of the submandibular space.

A mass is primary to the parotid space when the center of the lesion is within the parotid gland, lateral to the PPS. A larger, deep lobe parotid space mass displaces the PPS from lateral to medial with widening of the stylomandibular gap. A parotid space mass at the mandibular angle displaces the posterior belly of the digastric muscle medially. If perineural tumor is present, stylomastoid foramen fat will be replaced by tumor.

The oral cavity lies anterior to the oropharynx and below the sinonasal region. The oral cavity is separated from the oropharynx posteriorly by the circumvallate papillae, anterior tonsillar pillars, and soft palate. The oral mucosal space (OMS) lines the entire oral cavity, including the lips; buccal, gingival, and palatal surfaces; floor of the mouth (the semilunal mucosal surface overlying the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles); and the anterior two thirds of the oral tongue. No fascia exists to define the OMS. The retromolar trigone, a small region of mucosa behind the last molar on the mandibular ramus on both sides, is an anatomical crossroad of the oral cavity, oropharynx, soft palate, buccal space, masticator space, sublingual space, submandibular space, and PPS. The term root of the tongue is applied to the deep muscles (genioglossus and geniohyoid) of the oral tongue and the lingual septum. The mandible and maxilla are the defining bony margins of the oral cavity. Most masses in the oral cavity are amenable to direct clinical assessment. The vast majority of malignancies of OMS are squamous cell carcinomas, whereas minor salivary gland malignancies are relatively rare. Most infections of the oral cavity are dental in origin.

The sublingual space is a paired, nonfascial lined, fibro-fatty space of the oral cavity within the oral tongue superomedial to the mylohyoid muscle, lateral to the genioglossus/geniohyoid muscles, and anterior to the lingual tonsil. It is a teacup-shaped space that is situated within the confines of the mylohyoid muscle below the tongue. Communication between sublingual spaces occurs in the midline superoranteriorly as a narrow isthmus beneath the frenulum. The sublingual space communicates freely with the submandibular space and the inferior PPS at the posterior margin of the mylohyoid muscle. The posterior aspect of the sublingual space is divided by the hypoglossal muscle into medial and lateral compartments. The lateral compartment contains the hypoglossal and lingual nerve, combined with the chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve, sublingual glands and ducts, deep portion of the submandibular gland, and submandibular duct. Normal occupants of the medial compartment are the glossopharyngeal nerve and lingual artery and vein.

A mass is confined to the sublingual space when the center of the lesion is superomedial to the mylohyoid muscle and lateral to the genioglossus muscle. Lesions may escape the sublingual space into the submandibular space at the posterior margin of the mylohyoid muscle or through a cleft of the mylohyoid muscle between its anterior one third and posterior two thirds. Larger lesions of the sublingual space may cross the anterior midline under the frenulum of the tongue and become bilobular. At times a lesion will be herniated from the posterior sublingual space into the adjacent cephalad submandibular space and low PPS. The most common lesions of the sublingual space include squamous cell carcinoma arising from the epithelial lining of the sublingual space, abscess formation from odontogenic infection, a variety of congenital/developmental lesions, ranula, and an obstructed submandibular duct.

The submandibular space is the most inferior space of the suprahyoid neck. It is a horseshoe-shaped, fascial-lined space located inferolaterally to the mylohyoid muscle sling and deep to the platysma muscle, below the mandible and superiorly to the hyoid bone. It continues inferiorly into the infrahyoid neck as anterior cervical space. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia splits to encircle the submandibular space, with the deeper slip of fascia running along the external surface of the mylohyoid muscle and a more shallow slip paralleling the deep margin of the platysma. There is no midline fascia separating the two sides of the submandibular space. No fascial separation exists at the posterior margin of the mylohyoid muscle between the posterior submandibular and sublingual spaces and the inferior PPS. The principal contents of the submandibular space are the superficial portion of the submandibular gland, the submandibular and submental lymph nodes, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, the facial vein and artery, and the inferior loop of the hypoglossal nerve and fat. The parotid gland tail may project into the posterior submandibular space.

A mass is primary to the submandibular space when its center is within the submandibular space inferolateral to the mylohyoid muscle. With rare exceptions, lesions of the submandibular space do not decompress into the sublingual space (in contrast to the tendency of large masses of the sublingual space to work their way into the submandibular space). Most lesions of the submandibular space are from either the submandibular gland or nodes. In children, the most common lesions are second branchial cleft cysts. In adults, the most common pathology of the submandibular space is metastatic lymph nodes from squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity.

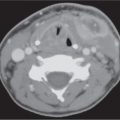

There are few diseases that do not follow the spatial anatomical confinement or involve multiple spaces, either contiguously or noncontiguously. The term transspatial is applied to disease processes that involve multiple contiguous spaces of the neck (Fig. 8.2). Transspatial diseases can be divided into three broad categories: developmental lesions, infections, and tumors. Transspatial developmental lesions include thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial cleft cysts, infantile hemangioma, vascular malformations, and macrocystic lymphatic malformations. Transspatial infectious diseases include cellulitis and abscesses, as well as diving ranulas. Transspatial benign tumors include lipomas, schwannomas, neurofibromas, juvenile angiofibromas, and aggressive fibromatosis. Any malignant tumor of the neck (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, both primary and metastatic, lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, thyroid carcinoma, minor salivary gland malignancies, and melanoma), if large or aggressive enough, can be found in multiple contiguous spaces at presentation.

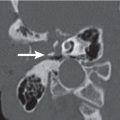

The term multispatial is applied to disease processes that involve multiple noncontiguous spaces of the neck. Multispatial diseases can be divided into nodal and nonnodal diseases (Figs. 8.3 , 8.4). Multispatial nodal diseases include malignant adenopathy (lymph node metastases and lymphoma) and non-malignant inflammatory adenopathy (any upper respiratory infection, either viral or bacterial, with reactive adenopathy; less frequently, mononucleosis, tularemia, tuberculosis, cat scratch fever, sarcoidosis, human immunodeficiency virus, Castleman disease, and Kimura disease). Nonnodal multispatial diseases include neurofibromatosis and systemic metastases.

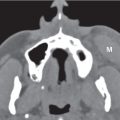

The cervical lymph nodes are arbitrarily grouped into levels I to VII (Figs. 8.5 , 8.6). Level I includes all the nodes above the hyoid bone, below the mylohyoid muscles, and anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the submandibular gland. Level IA represents the submental nodes that lie between the medial margins of the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles. Level IB represents the submandibular nodes that lie lateral and posterior to the medial edge of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Level II (upper jugular) nodes extend from the skull base to the lower body of the hyoid bone. They lie anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and posterior to a transverse line through the posterior edge of the submandibular gland. Level IIA nodes lie posterior to the internal jugular vein and are inseparable from the vein, or they lie anterior, medial, or lateral to the vein. Level IIB (upper spinal accessory) nodes lie posterior to the internal jugular vein with a fat plane separating the nodes and the vein. Retropharyngeal nodes, only present in suprahyoid neck, lie medial to the internal carotid artery. Level III (middle jugular) nodes lie between the level of the lower body of the hyoid bone and the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage. These nodes lie anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and lateral to the carotid arteries. Level IV (lower jugular) nodes lie between the level of the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage and the clavicle. These nodes lie anterior and medial to an oblique line drawn through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the posterolateral margin of the anterior scalene muscle on each axial image. Level IV nodes lie lateral to the common carotid artery. Level V (posterior triangle) nodes extend from the skull base to the level of the clavicle. Level V nodes all lie anterior to a transverse line drawn through the anterior edge of the trapezius muscle. Above the bottom of the cricoid arch, level VA nodes lie posterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Below the bottom of the cricoid arch, level VB nodes lie posterior and lateral to an oblique line through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the lateral posterior edge of the anterior scalene muscle. Supraclavicular nodes are the low level IV or V nodes that are seen on the images that contain a portion of the clavicle. Level VI (anterior compartment or visceral) nodes lie inferior to the lower body of the hyoid bone, superior to the top of the manubrium, and between the left and right carotid arteries. They include the juxtavisceral, anterior cervical, and external jugular nodes. Level VII (superior mediastinal) nodes lie caudal to the top of the manubrium in the superior mediastinum, between the left and right common carotid arteries. They extend caudally to the level of the in-nominate vein. Supraclavicular, retropharyngeal, parotid, facial, occipital, and postauricular nodal groups will still be referred to by their anatomical names.

A normal lymph node tends to be in the shape of a lima bean. The maximal diameter of a normal cervical lymph node varies from 3 to 11 mm; the greatest nodes are located in the submandibular and jugular digastric region. They are homogeneous, sharply delineated nodes, isodense to muscle with attenuation values from 40 to 50 Hounsfield units (HU), and enhancing slightly more than muscle on contrast-enhanced CT images. Fatty hilar metaplasia occurs almost exclusively at the periphery of the node as an area of low density. Cervical nodal calcifications are uncommon. In a child, metastatic neuroblastoma is the most common cause of calcified cervical lymph nodes. In adults, the most common cause of a calcified cervical lymph node is metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma and scrofula. Other less common causes of calcified lymph nodes are other nontubercular granulomatous infections, sarcoidosis, metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma, and healed irradiated carcinomatous and lymphomatous nodes. Eggshell-type calcifications can occur in silicosis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, scleroderma, amyloidosis, sinus histiocytosis, and massive lymphadenopathy treated with interferon. Cystic lymphadenopathy is the term used to describe nodes completely replaced by material similar in density to water (0–20 HU) with a thin or imperceptible wall. Some cystic nodes have increased protein content resulting in higher attenuation on CT (> 20 HU). Cystic nodes are seen in metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma and in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (base of the tongue and tonsil).

A space-specific differential diagnosis of pharyngeal mucosal space lesions as seen on CT is outlined in Table 8.1 , of PPS lesions in Table 8.2 , of masticator space lesions in Table 8.3 , of parotid space lesions in Table 8.4 , of suprahyoid carotid space lesions in Table 8.5 , of suprahyoid RPS lesions in Table 8.6 , of suprahyoid PVS lesions in Table 8.7 , of lesions of the mucosal area of the oral cavity in Table 8.8 , of submandibular space lesions in Table 8.9 , of sublingual space lesions in Table 8.10 , and of buccal space lesions in Table 8.11.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree