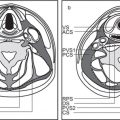

8 Suprahyoid Neck(Table 8.1 – Table 8.3)

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Asymmetric lateral pharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller) | Unilaterally collapsed pharyngeal recess, inflammatory debris or fluid in the lateral pharyngeal recess, or asymmetric adenoid tissue may mimic a mass lesion. Maintenance of soft tissue planes in the adjacent parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces strongly argues against a true mass lesion. | The lateral pharyngeal recess or fossa of Rosenmüller is the wide extent of the nasopharynx above the isthmus, located bilaterally just behind the opening of the auditory (eustachian) tube. A collapsed lateral pharyngeal recess can frequently be distended with the Valsalva maneuver, a modified Valsalva maneuver, or opening of the mouth widely. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

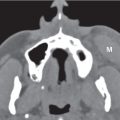

Tornwaldt cyst | Well-defined, round or ovoid, nonenhancing, fluid-filled, low-density mass with an imperceptible wall in the midline of the posterior nasopharyngeal wall between the longus capitis muscles without bone erosion. Size ranges from a few millimeters to 3 cm. Rare infected cyst may enhance peripherally. | Most common in young adults. Although usually asymptomatic, these cysts may become infected, giving rise to pain, halitosis, nasal discharge, and prevertebral muscle spasm. Differential diagnosis: Rathke pouch, a small epithelial cyst in the sphenoid body anterocephalad to Tornwaldt cyst. Uncommon and rare congenital cysts of the nasopharynx include transsphenoidal meningoencephalocele, neurenteric cyst, dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, cystic hamartoma, cystic teratoma, and extension of a second branchial cleft cyst or of a thymic cyst to the lateral pharyngeal wall. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Adenoidal and tonsillar hyperplasia | Symmetric involvement of the lymphatic tissue in the nasopharynx and oropharynx with attenuation similar to that of muscle, usually associated with hypertrophic faucial tonsils and reactive retropharyngeal and cervical adenopathy. Lingual tonsillar hyperplasia may be very prominent. | Immunobiological overactivity results in hyper-trophy of the lymphoepithelial tissue in the pharynx, most commonly the adenoid component, less commonly the faucial and lingual tonsils. Present in children and adolescents. |

Tonsillitis, tonsillar (peritonsillar) abscess | Tonsillitis presents as nonspecific, uni- or bilaterally tonsillar enlargement, with heterogeneous contrast enhancement, consistent with early infection and edema, bulging into the airway. Inflammatory changes may extend into the soft palate, parapharyngeal space, and masticator space. | Acute tonsillitis may be caused by viral or bacterial infection. Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Pneumococcus, Haemophilus, and Fusobacterium are the most common organisms. |

| Tonsillar abscess shows a swollen tonsil with central, uni- or multilocular low density and peripheral contrast-enhancing rim. When bilateral, tonsils may abut medially (“kissing tonsils”), obstructing the oropharyngeal airway. The abscess pocket is confined by the superior constrictor pharyngeal muscle to the pharyngeal mucosa space. No peritonsillar component is present. Peritonsillar abscess shows a pocket of fluid-like central areas of low attenuation within the enhancing cellulitic soft tissues of the peritonsillar area near the superior pole of the tonsil. When infection progresses, CT may show rupture of the abscess through the pharyngeal constrictor muscle into the parapharyngeal, masticator, and submandibular spaces. Most feared complication is extension of infection into the carotid space with septic thrombosis of the internal jugular vein or septic aneurysm of the carotid artery. Reactive bulky bilateral cervical adenopathy is common. | Usually occurs in children or young adults with sore throat and fever, followed by rapidly increasing painful swallowing, ear pain, and trismus. The disease is usually self-limited, but when it is severe, infection undergoes internal cavitations and suppuration, creating tonsillar or peritonsillar abscess. Peritonsillar abscess is the most common deep infection of the neck and chiefly involves patients between the ages of 10 and 40 y. |

Tonsilloliths | Solitary or multiple calcifications in the tonsil-lar region, unilateral or bilateral, 1 to 7 mm in size or larger. Less commonly, calculi are seen in the adenoids or lingual tonsil. | Postinflammatory dystrophic calcifications within the tonsils exist in as much as 10% of the population (men = women, mean age 55 y). Phleboliths of a tonsillar venous malformation may simulate tonsillar calculi. |

Postinflammatory mucus retention cyst | Well-defined, ovoid or pear-shaped, nonenhancing lesion of low (cystic) density in the nasopharynx, oropharynx, or vallecula, 1 to 2 cm, with no deep extension. Large cyst in the lateral pharyngeal recess may obstruct the eustachian tube, with resulting mastoid fluid. | Adult lesion. Usually an incidental finding. Rarely has any clinical significance. Nasopharnygeal pseudocysts have been postulated to be the result of a longus capitis perimyositis. Any of these cysts may become secondarily infected. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) | Submucosal, exophytic or, when large, pedunculated, oval to round, well-circumscribed, moderate-enhancing soft tissue mass, isodense to surrounding mucosa and muscle, encroaching upon the nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, or oropalatal airway. It may appear inhomogeneous secondary to hemorrhage, calcification, and necrosis. If the tumor is adjacent to bone (e.g., hard palate), benign-appearing remodeling may be seen on CT. | Benign mixed tumors may arise in the minor salivary glands located in the submucosal layer of the pharyngeal mucosal space, palates (most common minor salivary gland site), or tongue base. Rarely multifocal. Symptoms are size and location dependent. Most common age of presentation: 30 to 60 (M:F = 1:2). Other benign growths in the pharynx are squamous papilloma, (vascular) polyps, vascular malformations, lymphatic malformations, ectopic pituitary adenoma, extension of pituitary adenoma, hamartoma, teratoma, developmental cysts, and pedunculated fibroma. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Squamous cell carcinoma, nasopharynx | Usually large, polypoid or infiltrative, less-defined mass, isodense to muscle, with moderate contrast enhancement, most commonly arising from the lateral wall, including the fossa of Rosenmüller (82%), or from the midline (posterosuperior wall and inferior anterior wall of the nasopharynx) with asymmetrical thickening of the pharyngeal walls; tumor-caused deformity of the endopharyngeal contours, asymmetry of the fossa of Rosenmüller with blunting of the fossa, widening of the preoccipital soft tissue > 1.5 cm or nasopharyngeal soft tissue fullness. Nasopharyngeal carcinomas tend to grow via the mucosa or submucosa into the nasal cavity, oropharyngeal soft palate, and faucial tonsils. Because of its locally aggressive nature, nasopharyngeal cancer can penetrate the tough pharyngobasilar fascia and buccopharyngeal fascia with deep extension, loss of adjacent fat planes, and invasion into the parapharyngeal, masticator, carotid, and retropharyngeal space and prevertebral musculatures. Reactive increased sclerosis and destruction of the skull base usually occur directly over the tumor site, and extension through the skull base most often occurs via the foramen lacerum and the neural foramina of the middle cranial fossa floor. Perineural tumor spread primarily occurs after tumor has invaded the pterygopalatine fossa, foramen ovale, and hypoglossal canal. Further extension of tumor can involve the orbit, cavernous sinus, and even the brainstem. Nodal involvement may be extensive and bilateral. The nasopharyngeal carcinomas drain primarily into the lateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes and nodes of level II, followed by level V, level III, and the other cervical levels. | Malignant neoplasms of the nasopharynx include nasopharyngeal carcinomas (squamous cell carcinoma, low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma, other adenocarcinomas, and adenoid cystic carcinoma), non–Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, chloroma, extramedullary plasmocytoma, fibrosarcoma, carcinosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant schwannoma, liposarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, mucosal melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, extraosseous chordoma, chondrosarcoma, and metastasis. Biopsy is the best way to establish diagnosis, as imaging cannot distinguish among malignancies of the nasopharynx. The overwhelming majority of nasopharyngeal malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas (80%) with varying degrees of cellular differentiation. Epstein–Barr virus, certain types of human leukocyte antigens (HLA), and salted fish and vegetables have a strong association. There is a demographic predilection among Chinese and North Africans. In the United States, it accounts for ~0.25% of all cancers, with a higher occur-rence in men, usually over 40 y of age (there is an age peak among African Americans from 10 to 19 y old). A neck mass (due to jugular or spinal accessory lymphadenopathy) may be the first presenting symptom (at presentation, up to 90% of patients have regional nodal metastases, and at least 20% will have distant metastases). Tumor extension into the nasal cavity may present as epistaxis, nasal obstruction, or a nasal quality to the voice. Extension into the eustachian tube may present as hearing loss and serous otitis, whereas extension into the skull base with involvement of the cavernous sinuses may present as headache and cranial nerve palsies. |

|

| Carcinoma of the nasopharynx: TNM classification Primary tumor: T1: Tumor confined to the nasopharynx or extends to soft tissue of oropharynx and/or nasal fossa T2: Tumor with parapharyngeal extension* T3: Tumor invades skull base and/or paranasal sinuses T4: Tumor with intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves, infratemporal fossa, masticator space, hypopharynx, or orbit Regional lymph nodes: N1: Unilateral cervical node (s): ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension above supraclavicular fossa and/or retropharyngeal nodes N2: Bilateral node (s): ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension above supraclavicular fossa N3a: Metastases in lymph node (s) > 6 cm in dimension N3b: Extension to the supraclavicular fossa Distant metastasis: M1: Distant metastasis *Parapharyngeal extension denotes posterolateral infiltration of tumor beyond the pharyngobasilar fascia. |

Squamous cell carcinoma, oropharynx |

| Clinical tumor stage of oropharyngeal carcinoma: T1: Tumor ≤ 2 cm in its greatest dimension T2: Tumor > 2 cm but ≤ 4 cm in its greatest dimension T3: Tumor > 4 cm in its greatest dimension or extension to lingual surface of epiglottis T4a: Tumor invades the larynx, extrinsic muscles of the tongue, medial pterygoid, hard palate, or mandible T4b: Tumor invades lateral pterygoid muscle, pterygoid plates, lateral nasopharynx, or skull base, or encases carotid artery |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue Carcinoma of the base of the tongue is isodense to normal tongue muscle. Tumors are recognized as mucosal asymmetry, as mucosal-based exophytic lesion filling airway, by infiltration or obliteration of the normal fat planes of surrounding muscles, and by contrast enhancement of the tumor margins. Base of the tongue cancers may spread laterally into the mandible and medial pterygoid muscles; superiorly into the tonsillar fossa and soft palate; anteriorly into the mobile tongue and floor of the mouth; and inferiorly into the vallecula, pre-epiglottic space, and larynx or portions of the hypopharynx. The lingual tonsil carcinomas drain to nodes of level II, III, IV, and V. | Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue is an aggressive, deeply infiltrative tumor with a 75% incidence of lymph node metastases at presentation. Lesion is often asymptomatic until large in patients over 40 y of age (M > F) with a history of alcohol and tobacco use. |

Squamous cell carcinoma of the posterior pharyngeal wall Carcinomas of the posterior pharyngeal wall commonly present as an enhancing flat, thick tumor of soft tissue density, spreading at the mucosal surface and often involving both the nasopharynx and the hypopharynx with irregular narrowing of the lumen. They spread submucosally, invading the pharyngeal constrictors and the retropharyngeal space. Deep invasion of the prevertebral muscles is unusual at initial presentation. | Carcinomas of the posterior pharyngeal wall have the worst prognosis of all oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Lesion is often asymptomatic until large in patients over 40 y of age (M > F) with a history of alcohol and tobacco use. | |

Squamous cell carcinoma of the faucial tonsil Cancers of the tonsillar fossa usually arise near the upper pole of the tonsil as an enhancing mass with invasive deep margins. They may extend posterolaterally to the lateral pharyngeal wall, parapharyngeal space, and pterygoid muscles; inferiorly to the glossotonsillar sulcus, base of the tongue, and floor of the mouth; superiorly to the soft palate and nasopharynx; and anteriorly and posteriorly to the tonsillar pillars. Cancers of the anterior tonsillar pillar tend to spread superiorly into the soft and hard palate, nasopharynx, pterygoid muscles, and skull base; anteriorly into the buccinator muscle; and inferiorly along the palatoglossus muscle into the base of the tongue. Cancers of the posterior tonsillar pillar tend to spread superiorly into the soft palate, posteriorly into the posterior pharyngeal wall, and inferiorly into the pharyngoepiglottic fold. Bone erosion and carotid artery encasement are present in advanced stages. Lymph node metastases occur primarily in the upper jugular or retropharyngeal nodes, but the spinal accessory and submandibular nodes are also at risk. Carcinomas of the tonsil tend to produce cystic metastases. | Carcinomas of the tonsil account for 1.5% to 3% of all cancers. They have an overall 70% chance of having clinically positive nodal metastases at initial presentation. Lesion is often asymptomatic until large in patients over 40 y of age (M > F) with a history of alcohol and tobacco use. | |

Non–Hodgkin lymphoma | Involvement of the lymphatic tissue in the nasopharynx and oropharynx with smoothly marginated, exophytic, bulky submucosal mass, with attenuation similar to that of muscle. Deep invasion and bone destruction are uncommon. Associated adenopathy may be nonnecrotic, often bulky, and may be in atypical locations. Rarely associated extra-nodal sites are sinonasal cavity, orbit, parotid gland, larynx, and thyroid gland. | Second most common pharyngeal mucosal space malignancy in the adult. Patients are usually older than 40 y and may present with an adenoidal or tonsillar mass, associated systemic symptoms (fever, malaise, and hepatosplenomegaly), and distant adenopathy (present in 50% of cases). |

Minor salivary gland malignancy | Enhancing, well-circumscribed, smooth exophytic or irregular infiltrating pharyngeal mucosal space mass, often with deep extension into adjacent deep facial spaces. Rarely, minor salivary gland malignancies have metastatic adenopathy at presentation. | Rare, aggressive tumors arising from minor salivary glands in the pharyngeal mucosal space (soft palate > sinonasal cavity > tongue > lingual tonsil). Histologically, these tumors include adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, malignant mixed tumors, and acinic cell adenocarcinoma. More common in adult women, with submucosal, painful pharyngeal wall mass. More invasive lesions can have cranial neuropathy (cranial nerve [CN] V2, CN V3). |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | Bulky, heterogeneous, poorly marginated nasopharyngeal mass with variable, typically heterogeneous enhancement pattern. Associated osseous destructive changes to the skull base or remodeling of bone can be present. | In children, rhabdomyosarcoma is the third most common malignancy in the head and neck, following brain tumors and retinoblastoma. Rhabdomyosarcomas comprise 4% to 8% of all malignant tumors in children younger than 15 y. Forty percent of rhabdomyosarcomas arise in the head and neck, with the orbit and nasopharynx most commonly involved, followed by the para-nasal sinuses and middle ear. In the oropharynx, the base of the tongue is the predilection site. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Asymmetric pterygoid venous plexus | Unilateral pterygoid venous plexus enlargement with curvilinear contrast enhancement medial to pterygoid muscles and in the parapharyngeal space. Often seen on side of larger internal jugular vein. May be seen secondary to carotid-cavernous fistula. | Normal variant with unilateral prominence of an extensive network of small vascular channels in the medial masticator space and parapharyngeal space, draining the cavernous sinus and other intracranial venous channels (through the foramina ovale, spinale, lacerum, and foramen of Vesalius) and the deep facial vein to the maxillary vein. Usually asymptomatic; incidental CT or MRI finding may be mistaken for a focal vascular tumor. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Atypical second branchial cleft cyst | Nonenhancing, thin, smooth-walled, round or ovoid mass of fluid attenuation values extending from the deep margin of the faucial tonsil into the parapharyngeal fat toward the skull base and causing lateral pharyngeal wall displacement. When infected, the cyst wall may become thickened and irregular, the cyst content develops higher attenuation, and the surrounding fat planes may become obscured. | Although the most common location for a second branchial cleft cyst is the submandibular space, they can atypically present in the parapharyngeal space. Although congenital, the cysts most commonly present in young adults with parotid gland bulge, dysphagia, and vague neck discomfort, often after an upper respiratory tract infection. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Parapharyngeal space infection | CT may show an inflammatory mass or abscess of the parapharyngeal space with expansion and medial displacement of the tonsil and lateral pharyngeal wall. Cellulitis/phlegmon may appear as a soft tissue mass, often ill defined and enhancing, with obliteration of the parapharyngeal fat and obscuration of the adjacent enlarged muscles and pharyngeal mucosal space structures. Abscesses may present as uniloculated or multiloculated masses with air or fluid attenuation centers. Thick, irregular enhancing wall suggests mature abscess. Potential complications constitute internal jugular vein thrombosis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and arterial rupture and pseudo-aneurysm formation of the carotid arteries. | In the absence of penetrating trauma, a primary infectious process located in the pharynx, tonsils, adenoids, teeth, parotid gland, and paranasal sinuses may cause parapharyngeal space infection. Patients with parapharyngeal space infection are very sick, presenting with sudden onset of fever and chills. Trismus and CN IX to XII palsy and Horner syndrome may also be present. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) | Small tumors appear as sharply marginated, round or ovoid, isodense or hyperdense with parotid gland tissue, homogeneously mild to moderate enhancing mass centered within the parapharyngeal fat. Large tumors (> 2 cm) present as lobulated, well-circumscribed, inhomogeneously enhancing mass (in two-phase CT, these tumors present with an increase in attenuation during the second phase), with areas of low attenuation representing foci of necrosis, old hemorrhage, cysts, or fat. Focal areas of high-attenuation values represent dystrophic calcifications or ossifications in the tumor matrix. To diagnose an extraparotid origin, an intact fat plane between the tumor and the deep portion of the parotid gland must be clearly demonstrated. | Salivary gland tumors represent ~40% to 50% of parapharyngeal space masses (neurogenic tumors 17%–25%, paraganglioma ~10%). Benign mixed tumor is the most common salivary gland tumor. Benign mixed tumors in the parapharyngeal space commonly arise from the deep lobe of the parotid gland and extend into the parapharyngeal space through the stylomandibular tunnel. However, they can also arise from minor salivary glands of the pharyngeal mucosa or primarily within the parapharyngeal space from congenital rests of salivary gland tissue. Benign mixed tumors are typically seen in middle-aged women and present as a slowly growing painless mass, pushing a tonsil into the pharyngeal airway. |

Lipoma | Well-defined, nonenhancing fat density mass (–65 to –125 HU), homogeneous without any internal soft tissue stranding. Liposarcoma may also be a concern if there is prominent internal stranding, enhancing nodularity, or inhomogeneity. | Uncommon lesions in the parapharyngeal space. Peak age of occurrence is 40 y and older (M:F = 2.5:1). |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Malignancies of salivary gland origin | Moderate enhancing soft tissue mass with irregular, ill-defined margins or infiltration of surrounding tissues. Differentiation from benign tumors may be difficult, as two thirds of salivary gland malignancies have smooth, well-defined margins. | Malignant tumors of the parapharyngeal space are much less common than benign lesions and include malignant lesions of salivary gland origin (especially mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and acinic cell carcinoma), along with direct invasion of malignancies of the adjacent spaces. |

Contiguous tumor extension | Obliteration of the parapharyngeal fat due to an infiltrating soft tissue mass with its center in the pharyngeal mucosal space (squamous cell carcinoma, non–Hodgkin lymphoma, and minor salivary gland malignancy); in the masticator space (e.g., sarcoma of the mandible or surrounding soft tissues and malignant neurogenic lesion); in the parotid space (e.g., mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma); and in the submandibular space (squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity) or the skull base (metastatic disease). | Direct spread of malignant tumor from adjacent deep facial space: these malignant tumors break out of their space of origin and invade the parapharyngeal space. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Asymmetric pterygoid venous plexus | Unilateral pterygoid venous plexus enlargement with curvilinear contrast enhancement medial to pterygoid muscles and in the parapharyngeal space. Often seen on side of larger internal jugular vein. May be seen secondary to carotid-cavernous fistula. | Normal variant with unilateral prominence of an extensive network of small vascular channels in the medial masticator space and parapharyngeal space, draining above the cavernous sinus and other intracranial venous channels (through the foramina ovale, spinale, lacerum, and foramen of Vesalius) and the deep facial vein to the maxillary vein. Usually asymptomatic; incidental CT or MRI finding may be mistaken for a focal vascular tumor. |

Benign masticator muscle hypertrophy | Unilateral or bilateral diffuse, homogeneous enlargement of masticator muscles. The masseter muscle is most obviously affected. Enlarged muscles are isodense to normal skeletal muscles and enhance normally. Cortical thickening affecting mandible and zygomatic arch may be observed, or a rough bony projection of cortical bone along the anterior surface of the mandible at the site of the masseter insertion; also, normally preserved fascial and soft tissue planes. | Presents as nontender lateral facial mass; may be familial. Acquired form is usually secondary to nocturnal teeth clenching. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dys-function or malocclusion may also contribute. |

CN V3 denervation atrophy | Most frequently unilateral. CT is relatively insensitive to acute and subacute denervation changes. Long-standing chronic denervation is manifested by marked loss of volume and extensive fatty replacement of the affected muscles of mastication. Ipsilateral asymmetry of the torus tubarius and fluid in the mastoid cells due to tensor veli palatini denervation and eustachian tube dysfunction are additional findings. Contralateral masticator muscle atrophy makes normal masticator space appear hypertrophic. | Damage to the mandibular nerve may be seen with malignant or benign tumors involving the third division of the trigeminal nerve, after surgery and trauma, and with infection; more common in adults due to prevalence of head and neck tumors and surgery. If all muscles innervated by mandibular nerve are involved (medial and lateral pterygoid, masseter, temporalis, tensor veli palatini, mylohyoid, and anterior belly of digastric muscle), then lesion is between root exit zone of lateral pons and foramen ovale. If only mylohyoid and anterior belly digastric muscle are involved, lesion is between the skull base and mandibular foramen. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Infantile hemangioma (capillary hemangioma) | Solitary, multifocal, or transspatial, lobular cervicofacial soft tissue mass, homogeneous and isodense with muscle. Contrast enhancement is uniform and intense. No calcifications. Can be very large, occupying, filling, and expanding the masticator space. Commonly involves the masseter muscle. Bony deformity or skeletal hyper-trophy may be associated with infantile hemangioma, but intraosseous invasion is extremely uncommon. Size, enhancement, and vascularity of tumor regress in involutional phase with internal, low-density fat. | Most common infant tumors; typically present in early infancy with rapid growth and ultimately involute via fatty replacement by adolescence. Infantile hemangiomas are high-flow lesions during their proliferative phase, low-flow lesions in their involutional phase. Sixty percent of infantile hemangiomas occur in head and neck, with superficial strawberry-colored lesions and facial swelling and/or deep lesions, often in parotid, masticator, and buccal spaces. Retropharyngeal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces, along with oral mucosa, are other common locations. |

Venous vascular malformation (cavernous hemangioma) | Extraparotid, lobulated or poorly marginated soft tissue mass, isodense to muscle, with rounded calcifications (phleboliths). May be superficial or deep, localized or diffuse, solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or transspatial, with or without satellite lesions. Contrast enhancement is patchy or homogeneous and intense. Bony deformity of the adjacent mandible or posterolateral wall of the maxillary antrum may occur, as well as fat hypertrophy in adjacent soft tissues. | Venous vascular malformations are congenital low-flow, nontumorous vascular malformations, have an equal gender incidence, may not become clinically apparent until late infancy or childhood, virtually always grow in size with the patient during childhood, and do not involute spontaneously. Most are found in the buccal region. Masticator space, sublingual space, tongue, orbit, and dorsal neck are other common locations. Frequently, venous malformations do not respect fascial boundaries and commonly involve more than one deep fascial space. They are soft and compressible. Lesion may increase in size with Valsalva maneuver, bending over, or crying. Swelling and enlargement can occur following trauma or hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy). Pain is common and often caused by thrombosis. |

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma, cystic hygroma) | Uni- or multiloculated, nonenhancing, fluid-filled low-density mass with imperceptible wall, which tends to invaginate between normal structures. Often found in multiple contiguous cervical spaces (transspatial). Rapid enlargement of the lesion, areas of high attenuation values and fluid–fluid levels suggest prior hemorrhage. Lymphatic and venous malformation may coexist. | Lymphatic malformations represent a spectrum of congenital low-flow vascular malformations, differentiated by size of dilated lymphatic channels. Macro-cystic lymphatic malformation is the most common subtype. Sixty-five percent are present at birth; 90% are clinically apparent by 3 y of age. The remaining 10% present in young adults. In the suprahyoid neck, the masticator and submandibular spaces are the most common locations. May be sporadic or part of congenital syndromes (e.g., Turner, Noonan, and fetal alcohol syndromes). |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

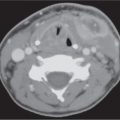

Masticator space infection | Cellulitis/phlegmon of the masticator space may appear as a soft tissue mass, often ill-defined, with swollen enhancing masticator muscles and obliteration of fat planes. The parapharyngeal space may be compressed posteromedially by edematous medial pterygoid muscle. Overlying subcutaneous tissues often demonstrate linear stranding or mottled increased attenuation beneath thickened skin. Abscesses may present as uniloculated or multiloculated, ovoid to round mass with air or fluid attenuation centers. A thick, irregular enhancing wall suggests mature abscess. Surrounding tissues are edematous. Masticator space infection may be accompanied by mandibular osteomyelitis and airway encroachment. Infection may spread into the suprazygomatic and nasopharyngeal masticator spaces, causing osteomyelitis of the skull base, or extend inferiorly into the floor of the mouth and upper neck. | Masticator space infection originates most commonly from second or third molar tooth infection (parodontal or periapical abscess in the mandible that may demonstrate signs of osteomyelitis) or following dental procedure. Masticator space cellulitis and abscess formation may also occur as a complication of mandibular or zygomatic arch fractures, especially when treated with internal fixation. Infection may also extend to the masticator space from adjacent areas in the neck. Odontogenic abscess is the most common lesion of the masticator space. Painful jaw swelling, fever, trismus, induration over the angle and ramus of the mandible, and elevated white blood cell count (WBC) are often present. |

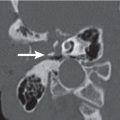

Mandibular osteomyelitis | CT findings include periosteal new bone formation, localized cortical breakdown associated with increased attenuation within the medullary cavity and poorly defined lucencies within the bone, often accompanied by extension of infection into the adjacent spaces with sinus tracts, myositis, fasciitis, cellulitis, and abscess formation. In long-standing infection, bony sequestra and sclerosis may be seen. | Acute osteomyelitis of the mandible most often results from tooth infection, less often from adjacent deep space infection, from dental manipulation, following surgical procedures or penetrating trauma. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Ameloblastoma | Expansile, unilocular or “bubbly,” multilocular, mixed cystic-solid mass emanating from the molar/ramous area of the mandible or from the premolar/first molar region of the maxilla with scalloped borders. May have a honeycombed appearance with bony septa. A matrix calcification is rare with the exception of desmoplastic ameloblastoma. An unerupted molar tooth association and resorption of adjacent teeth are common. The lesion often demonstrates marked expansion with thinned or imperceptible cortical shell. Larger lesions with extraosseous extension show extensive soft tissue enhancement mixed with cystic low-density areas. | Most common odontogenic and benign mandibular tumor. Mandible:maxilla ratio = 5:1. Most commonly manifests from age 30 to 50 y (M = F) with a slow-growing painless mass of the affected area. High recurrence rate (33%); malignant transformation is rare (1%). Other benign expansile mandibular masses include odontogenic keratocyst, dentigerous cyst, giant cell reparative granuloma, brown tumor, giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst, hemangioma, cystic fibrous dysplasia, and ossifying fibroma. |

Schwannoma | Sharply and smoothly marginated, ovoid to fusiform, homogeneous soft tissue mass along the course of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, isodense to hypodense relative to muscle, with variable, often intense contrast enhancement. Large tumors may undergo cystic degeneration and present with central unenhancing and peripheral enhancing areas. Calcifications are exceptional. Smooth, corticated enlargement of the bony foramen and canal involved are typical of change from V3 schwannoma. | Schwannomas of the masticator space are usually of mandibular nerve origin (CN V3) and may be located anywhere along its extracranial course. However, involvement of the mandibular nerve is rare. Schwannomas more rarely affect CN V3 branches, including inferior alveolar and mental nerves. Can be multifocal in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2; occurs in patients in their 30s to 40s. Even large lesions may be asymptomatic. Long-standing chronic denervation is manifested by marked loss of volume and extensive fatty replacement of the affected muscles of mastication. |

Neurofibroma | Solitary neurofibroma: Fusiform, ovoid or tubular sharply circumscribed mass, isodense to hypodense relative to cervical cord, smooth and surrounded by fat planes. Differs from schwannoma by an overall lower density that may approach water and conspicuous absence of contrast enhancement. Rarely undergoes cystic degeneration. Plexiform neurofibroma: Usually large, diffuse, ill-defined, lobulated, multinodular, low-density mass involving multiple cervical compartments (transspatial), including the masticator space. A typical sign is the target sign with central punctate enhancement surrounded by peripheral low attenuation within multiple tumor nodules. Neurofibromas observed in von Recklinghausen disease characteristically occur at multiple sites and are often confluent, multiple, or plexiform. | About 50% of all neurofibroma cases are sporadic, ~50% are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurofibromas of the masticator space arise from the inferior alveolar nerve, mylohyoid branch, or masticator nerve branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3). Can occur at any age, with average 35 y (female predominance). These neoplasms grow slowly and are painless. Two to 6% of lesions in neurofibromatosis type 1 may undergo malignant transformation. |

Aggressive fibromatosis (extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis, juvenile fibromatosis) | “Malignant-appearing,” poorly marginated inhomogeneously enhancing transspatial soft tissue mass with local invasion of muscle, vessels, nerves, and bone. Most common locations are perivertebral space, supraclavicular area, and masticator space. | Benign soft tissue tumor of fibroblastic origin arising from aponeurotic neck structures. Associated abnormality: Gardner syndrome. Seen at all ages (70% younger than 35 y). Significantly more women affected. Patients present with firm, painless neck mass. Paresis depends on site. Postoperative recurrence rate may reach 25%. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Contiguous tumor extension | Invasive masticator space mass, often demonstrating cortical erosion or destruction of the adjacent mandible. | Invasion of the masticator space is usually a late manifestation of carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, external auditory canal, or salivary gland. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma may enter the masticator space by direct extension from the faucial tonsil or retromolar trigone, by way of direct mandibular invasion from the floor of the mouth, or via perineural tumor spread along the mandibular and lingual nerves, which originate from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. |

Sarcomas | Sarcomas of the masticator space present as often large, poorly marginated, heterogeneous masses with intermediate attenuation values and variable, heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Bone production or calcifications are most commonly seen in osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Bone fragments within tumors can be present in any masticator space sarcoma with extensive bone destruction of the mandibular, zygomatic arch, or pterygoid plate. There may be invasion of adjacent fascial planes and spaces. Masticator space sarcomas can spread by direct extension into the middle cranial fossa or into the pterygopalatine fossa. Perineural tumor spread on CN V3 can occur anywhere along its course with enhancement of the enlarged nerve, obscuration of the fat planes around the nerve, and enlargement of its foramen or canal. | Primary malignant tumors of the masticator space are uncommon. They include sarcomas of the mandible or surrounding soft tissues and malignant neurogenic lesions. Chondrosarcoma arises from the TMJ and jaws. Soft tissue extension of osteosarcomas involves the masticator space when the angle, ramus, or condyle is the primary site of involvement. The most common masticator space sarcoma in the pediatric population is a rhabdomyosarcoma (first and second decades, rare in adults). |

Malignant schwannoma | Tubular mass along the course of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve and its primary branches within the masticator space. Extension through the enlarged foramen ovale to involve the gasserian ganglion is not uncommon with this lesion. | Malignant nerve sheath tumors arising from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve are rare. |

Non–Hodgkin lymphoma | Ill-defined and infiltrative masticator space mass, isolated or associated with nodal disease, extranodal lymphatic disease (Waldeyer ring), and/or involvement of other extranodal, extralymphatic sites (e.g., sinus, nose, and orbit). | Patients may have CN V3 symptoms and masticator space mass as part of systemic non–Hodgkin lymphoma or as the first manifestation of limited head and neck disease. |

Mandibular metastases | Metastases typically manifest as ill-defined mandibular destructive soft tissue attenuating masses, often with extension into surrounding tissues. The posterior body and angle are most commonly affected. Some blastic lesions, such as prostate metastasis, may occur. | Metastases to the mandible are four times more common than to the maxilla. However, metastasis to the mandible is uncommon. Usually occurs as a multifocal disease in the setting of known primary tumor (breast, lung, renal, or prostate cancer). Metastases may be asymptomatic or may cause pain and CN V3 numbness. |

Metabolic disorder | ||

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease | CT usually demonstrates fine irregular and linear periarticular and intra-articular calcifications (chondrocalcinosis) with degenerative changes of the joint (metabolic arthritis). Tumorous calcified collections with mass effect or destruction of the temporal bone and mandibular condyle are occasionally observed in the TMJ. | Metabolic arthritis, which can accompany calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (“pseudo-gout”), is rare in the TMJ. Men and women older than 50 y are equally affected. Symptoms related to TMJ involvement are sudden attacks with pain, joint swelling, trismus, abnormal occlusion, and conductive hearing loss. Other crystal-associated arthropathies are gout, calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition disease, and chronic renal failure. |

Related posts:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree