Abdominal Aorta

Anthony J. Dean

INTRODUCTION

Timely emergency department (ED) diagnosis of acute abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is vital. An AAA is usually defined as focal dilatation of the abdominal aorta of 150% of normal (1). Since the normal mean aortic diameter is 2 cm (range 1.4 to 3.0 cm), aneurysm is defined as an infrarenal aortic diameter of >3 cm. The upper limit of normal size of the iliac arteries, which may be involved in aneurysmal disease alone, or (more commonly) with AAA, is 1.5 cm. Once an aorta becomes aneurysmal, growth rate is highly variable, with 20% of AAAs not expanding, and 20% expanding at >5 mm per year (2, 3, 4). For those that do expand, growth rate is exponential: the larger the aneurysm, the more rapidly it expands (2,4,5). The likelihood of rupture is also strongly linked to size (Table 10.1). Rupture of an AAA causes about 6000 deaths annually in the United States (6,7). Mortality rates from AAA have fallen significantly in the past decade, most likely due to the combined benefits of earlier diagnosis through screening programs leading to higher rates of elective repair, and improved surgical techniques leading to lower elective operative mortality (6, 7, 8).

TABLE 10.1 One- and Five-Year Rupture Rates from AAAs of Various Sizes | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Most AAAs are asymptomatic until they rupture, making this a disease that can only be effectively managed by early detection (9,10). The utility of emergency bedside ultrasonography is most compelling in time-sensitive and potentially lethal diseases. Emergency bedside ultrasound is highly sensitive (>90%) in the detection of AAA when performed by emergency physicians (11, 12, 13, 14, 15). It will reliably identify all AAAs when performed in a systematic and thorough way unless impeded by bowel gas or a very large pannus (an “indeterminate exam”). Thus, while the accurate interpretation of images is essential, an even more important task is the determination of whether or not a complete and adequate exam has been performed. The cardinal virtue of an emergency physician—to know with certainty what one does or does not know—applies especially when wielding an ultrasound probe. This chapter, in addition to describing the sonographic findings of a normal and abnormal aorta exam, will focus on techniques to promote, and pitfalls to avoid, in obtaining a complete exam.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

The primary application for ultrasound of the aorta is the rapid bedside detection of an AAA. Since patients with an AAA present with a variety of symptoms (Table 10.2), early bedside imaging might detect AAAs in patients whose diagnosis might otherwise be delayed or missed altogether while awaiting other testing either in the ED or as an outpatient. The majority present with back pain and/or abdominal pain (16,17). In one series, 39% of patients presented with vomiting (17). Fewer than one-quarter of patients are aware that they have an aneurysm before presenting with complications (16). The physical exam is also unreliable for the detection of AAA (16,18). The triad of hypotension, back pain, and a pulsatile mass is present in only a quarter of cases of ruptured AAA (19). Based on clinical exam alone, acute AAA is misdiagnosed 30% to 60% of the time (16,17,20).

Underdiagnosis is much more common than overdiagnosis. Common misdiagnoses include gastrointestinal disorders (diverticulitis, cancer, appendicitis, constipation) in up to half of cases, urinary obstruction or infection (33%), and spinal disease (25%). Thus, the diagnosis of both acute and asymptomatic AAA depends upon diagnostic imaging.

TABLE 10.2 Clinical Findings in Acute AAA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Traditionally, descriptions of acute AAA have distinguished between those that are “ruptured” and those that are “expanding.” Since some patients with symptomatic AAA survive for prolonged periods (21), and some resected AAAs show only edema or microscopic signs of hemorrhage (22), there is pathological basis for this distinction. However, for the emergency physician the distinction is moot, since a nonruptured “expanding” aneurysm is treated in the same way as one that is actively leaking. The two key determinations for the emergency physician are, first, “does this patient with a clinical picture suggesting the possibility of AAA actually have an aneurysm?” And, second, “If so, is it actually the cause of the patient’s symptoms, or is it an incidental finding?”

Following rupture or leaking of the aneurysm, patients may present in hypovolemic shock. In these critical patients, bedside ultrasound is performed at the same time as resuscitation. However, ultrasound rarely detects retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and patients with intraperitoneal rupture usually die immediately, so explicit signs of rupture are usually not seen. Thus, the detection of an aneurysm in a hypotensive, critically ill patient is sufficient grounds for immediate vascular surgery consultation. In rare cases, the identification of an AAA in a patient in pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest may represent an opportunity for emergent vascular salvage (23).

It is estimated that about 5% of men above the age of 65 have an AAA (6). Elective repair of AAA has a mortality of 2-4% with current operative techniques. In contrast, <50% of patients survive rupture to be taken to surgery, and among these, surgical mortality is >50% (24). Following the demonstration of the utility of ultrasound as a screening tool for asymptomatic AAA in clinic populations in the United Kingdom, there has been some interest in the deployment of screening ultrasound in the ED (25, 26, 27, 28, 29). However, more recent literature has raised questions about the accuracy of ED measurements of smaller aneurysms, as well as the practicality of performing screening exams on large numbers of asymptomatic patients in busy EDs (30,31).

IMAGE ACQUISITION

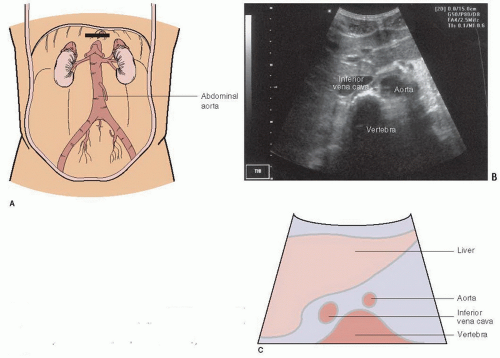

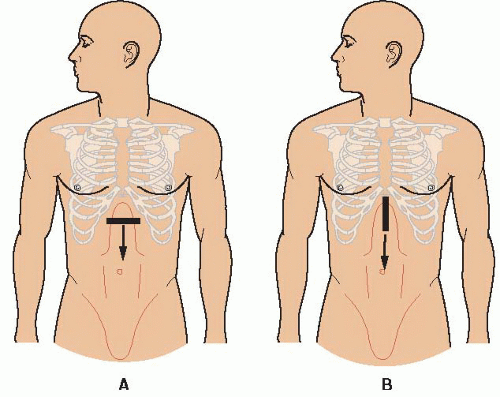

The patient is initially and almost exclusively examined in the supine position (Fig. 10.1). For the majority of adults, a 2.5 to 3.5 MHz curved array transducer provides adequate tissue penetration and sufficient resolution to examine the aorta, although a phased array probe can also be used. An image depth of 20 cm is usually adequate to identify the vertebral body, which serves as an important landmark for the aorta. For patients with a high body mass index, a lowfrequency range should be selected. The depth should be adjusted to optimize the image once the aorta is located, keeping the aorta in the midfield. Tissue harmonic imaging, if available, may provide better images in the presence of extensive bowel gas.

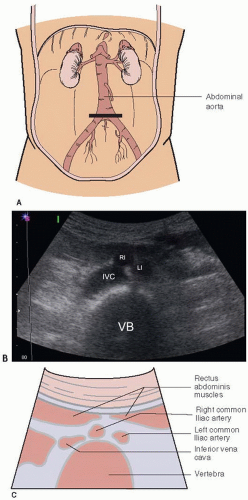

The exam begins with the transducer in the midepigastrium in the transverse plane with the patient in a supine position (Fig. 10.1). This position is similar to the subxyphoid window used to visualize the heart and pericardium. Standard transverse abdominal ultrasound orientation has the indicator on the transducer pointing toward the patient’s right. The liver is visualized in the upper left corner of the monitor screen and acts as an acoustic window to view other structures (Fig. 10.2). The anterior aspect of the vertebral body is often the first visible landmark. This appears as a hyperechoic, shadow-casting arch (Fig. 10.2). The aorta lies just anterior to the vertebral body, and appears as an anechoic cylinder. The inferior vena cava (IVC) lies just to the right of the aorta (Fig. 10.2). Once a midline view is obtained, the identity of the aorta should be confirmed by visualizing either the celiac trunk or the superior mesenteric artery, and the IVC should be located to confirm its identity. The aorta should be imaged in its entirety, scanning in the epigastrium, from the take off of the celiac trunk, all the way to its bifurcation into the common iliacs (Fig. 10.3; eFig. 10.1;  VIDEO 10.1). Once the full aorta has been imaged in transverse orientation, a longitudinal view is obtained by rotating the transducer to move the indicator to a 12-o’clock position; this projects the head of the patient toward the left of the monitor screen (Fig. 10.4; eFig. 10.2;

VIDEO 10.1). Once the full aorta has been imaged in transverse orientation, a longitudinal view is obtained by rotating the transducer to move the indicator to a 12-o’clock position; this projects the head of the patient toward the left of the monitor screen (Fig. 10.4; eFig. 10.2;  VIDEO 10.2). Whenever possible, it is ideal to maintain the transducer at the epigastrium in order to take full advantage of the liver as

VIDEO 10.2). Whenever possible, it is ideal to maintain the transducer at the epigastrium in order to take full advantage of the liver as

an acoustic window. It can then be projected caudad without actually moving the transducer from the epigastrium, and the aorta can be followed as inferiorly as possible. Because 95% of AAAs are distal to the renal arteries, it is important to visualize the abdominal aorta in its entirety from the diaphragm to the bifurcation (14).

VIDEO 10.1). Once the full aorta has been imaged in transverse orientation, a longitudinal view is obtained by rotating the transducer to move the indicator to a 12-o’clock position; this projects the head of the patient toward the left of the monitor screen (Fig. 10.4; eFig. 10.2;

VIDEO 10.1). Once the full aorta has been imaged in transverse orientation, a longitudinal view is obtained by rotating the transducer to move the indicator to a 12-o’clock position; this projects the head of the patient toward the left of the monitor screen (Fig. 10.4; eFig. 10.2;  VIDEO 10.2). Whenever possible, it is ideal to maintain the transducer at the epigastrium in order to take full advantage of the liver as

VIDEO 10.2). Whenever possible, it is ideal to maintain the transducer at the epigastrium in order to take full advantage of the liver as an acoustic window. It can then be projected caudad without actually moving the transducer from the epigastrium, and the aorta can be followed as inferiorly as possible. Because 95% of AAAs are distal to the renal arteries, it is important to visualize the abdominal aorta in its entirety from the diaphragm to the bifurcation (14).

FIGURE 10.1. Guide to Image Acquisition: The Aorta. Begin in the midline of the epigastrium and scan down the abdomen to the umbilicus in both transverse (A) and longitudinal (B) orientations. |

Bowel gas and obesity are constant challenges to aortic imaging. Gentle, constant pressure, sometimes assisted by a jiggling motion, is often successful in displacing loops of gas-filled bowel ( VIDEO 10.3). In fact, one of the pitfalls in imaging the aorta is moving the transducer away from an area of bowel gas too quickly. In refractory cases, an

VIDEO 10.3). In fact, one of the pitfalls in imaging the aorta is moving the transducer away from an area of bowel gas too quickly. In refractory cases, an

alternative to the supine position is placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position and scanning in a coronal plane in the midaxillary line between the ribs or below the costal margin (Fig. 10.5; eFig. 10.3). This approach takes advantage of the liver as an acoustic window and provides a longitudinal image of the aorta. Views of the infrarenal aorta are likely to be limited using this window, so that a complete evaluation is rarely possible; but if an aneurysm is identified, management decisions can be expedited. If difficulty is encountered in scanning the distal aorta, views from the left side of the umbilicus or below it can sometimes be helpful.

VIDEO 10.3). In fact, one of the pitfalls in imaging the aorta is moving the transducer away from an area of bowel gas too quickly. In refractory cases, an

VIDEO 10.3). In fact, one of the pitfalls in imaging the aorta is moving the transducer away from an area of bowel gas too quickly. In refractory cases, an alternative to the supine position is placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position and scanning in a coronal plane in the midaxillary line between the ribs or below the costal margin (Fig. 10.5; eFig. 10.3). This approach takes advantage of the liver as an acoustic window and provides a longitudinal image of the aorta. Views of the infrarenal aorta are likely to be limited using this window, so that a complete evaluation is rarely possible; but if an aneurysm is identified, management decisions can be expedited. If difficulty is encountered in scanning the distal aorta, views from the left side of the umbilicus or below it can sometimes be helpful.

FIGURE 10.3. A: Short axis view of the aorta at the umbilicus, the level of the bifurcation. B: Ultrasound at the aortic bifurcation. C: Bifurcation of the aorta into the common iliac arteries. IVC, inferior vena cava; RI, right iliac; LI, left iliac; VB, vertebral body.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|