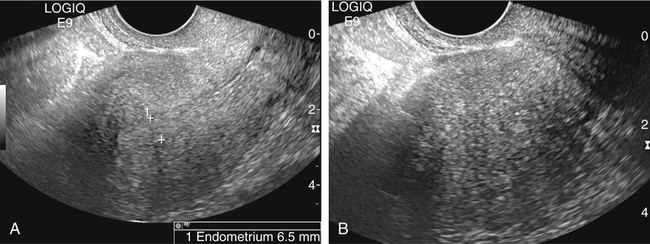

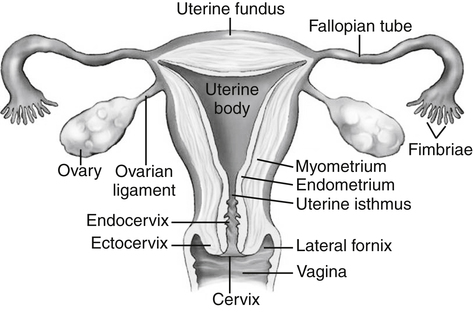

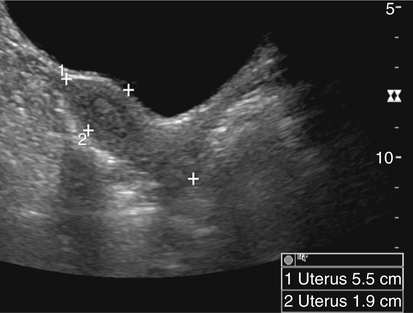

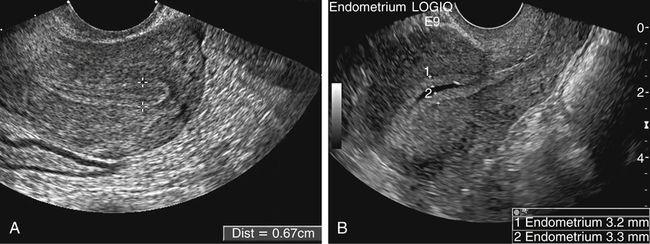

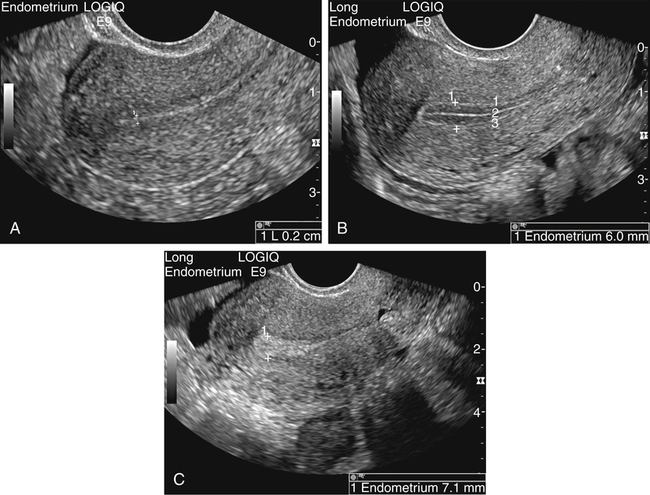

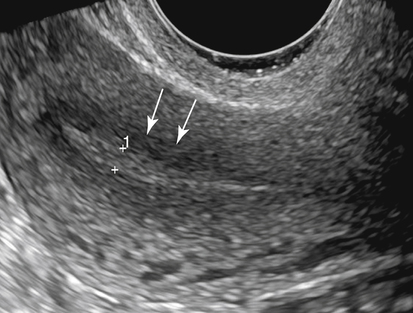

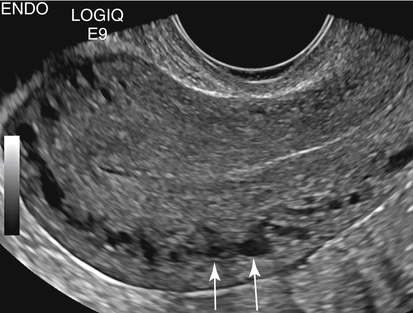

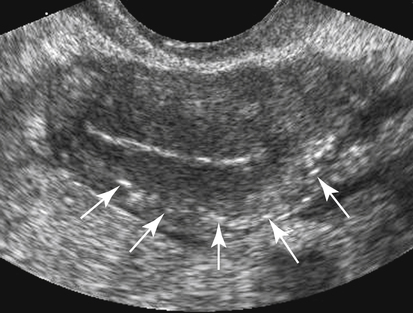

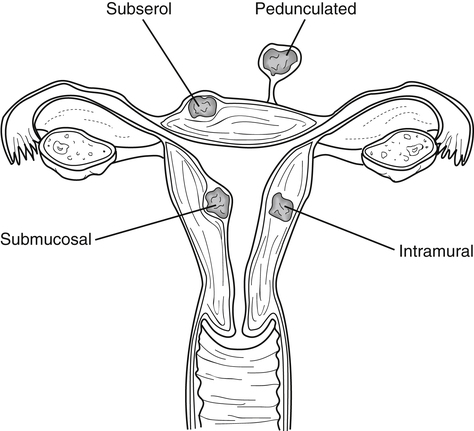

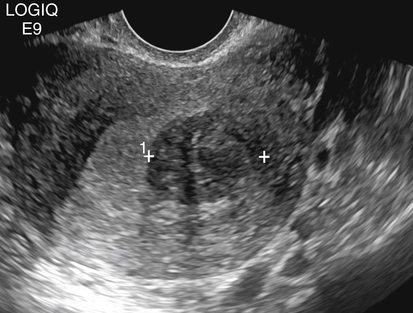

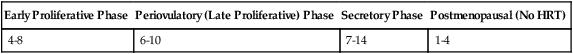

• List the most common conditions associated with abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant patients. • Differentiate the sonographic appearances of pathologies involving the myometrium and endometrium. • Describe appropriate imaging studies available for evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. • Discuss treatment options for the most common causes of abnormal uterine bleeding. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a common problem for which pelvic sonography is indicated. Patients may see a health care provider because of infrequent menses, prolonged and heavy menses (menorrhagia), intermenstrual bleeding or spotting, postcoital spotting, or irregular and heavy menses (menometrorrhagia). Many possible diagnoses are considered in the evaluation of AUB. AUB may arise from structural causes, such as a lesion within the uterus or endometrium, or from a reproductive tract abnormality. AUB that is not caused by a structural problem is usually endocrine in nature and is called dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB). Causes of AUB are listed in Box 13-1. The normal uterus is a pear-shaped organ located in the midpelvis, posterior to the urinary bladder and anterior to the rectum. The uterine divisions include the cervix, body, and fundus. The entrance to each fallopian tube, called the cornu (pl. cornua), is located in the uterine fundus. Uterine tissue consists of three layers: serosa, myometrium, and endometrium. The serosal layer (perimetrium) is the thin outer layer surrounding the uterus, the myometrium is the thick middle muscular layer, and the endometrium is the functional inner lining of the uterus (Fig. 13-2). The endometrium consists of a basal and a functional layer. The functional layer responds to hormonal stimulation throughout the menstrual cycle and is the layer that sheds during menses. The normal sonographic appearance of the uterus depends on age, menstrual status, and parity. Uterine size varies throughout a woman’s life, depending on hormonal stimulation, pregnancy, and anatomic disorders. After menarche but before childbirth, the uterus measures approximately 8 cm long, 5 cm wide, and 4 cm thick. Parity generally increases uterine size by about 1 cm in all dimensions. After menopause, the uterus decreases in size. By age 65 years, uterine size ranges from 3.5 to 6.5 cm in length and 1 to 2 cm in diameter.1 The length and anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the uterus are obtained in the longitudinal midline view by measuring from the top of the uterine fundus to the external cervical os (Fig. 13-3). The sonographic appearance of the normal endometrium depends on the menstrual phase or status of the patient and should be homogeneous in appearance and of appropriate thickness for the woman’s menstrual status (Table 13-1). An AP measurement of the double layer endometrial thickness should be obtained while in the longitudinal scanning plane, with placement of the calipers at the outer edges of each echogenic basal layer (Fig. 13-4, A). When intercavitary fluid is present, the endometrial layers should be measured separately, with the sum of the two measurements representing endometrial thickness (Fig. 13-4, B). For menstrual age women, normal double layer endometrial thickness is 4 to 14 mm, with maximum thickness occurring during the secretory phase. Endometrial pathology is very unlikely in a postmenopausal woman if endometrial thickness is less than 5 mm.2 Postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy can experience a slightly thickened endometrium during the estrogen cycle (up to 8 mm) and should undergo repeat scanning during the progesterone cycle. TABLE 13-1 Normal Endometrial Thickness (mm) HRT, Hormone replacement therapy. From Salem S: Gynecologic ultrasound. In: Rumack C, Wilson S, Charboneau J, et al, editors: Diagnostic ultrasound, vol 1, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2011, Mosby:547-612. The functional layer of the endometrium demonstrates changes in sonographic appearance throughout the menstrual cycle. During menses, the endometrium is thin and appears as a hyperechoic line (Fig. 13-5, A). As the proliferative phase progresses and ovulation approaches, a triple line appearance is created by the opposite hyperechoic basal layers, hypoechoic functional layer, and hyperechoic endometrial cavity (Fig. 13-5, B). The secretory phase results in a thickened endometrium hyperechoic to the myometrium (Fig. 13-5, C). The inner layer of myometrium adjacent to the basal layer of the endometrium appears as a hypoechoic rim and is sometimes referred to as the junctional zone or subendometrial halo (Fig. 13-6); this should not be included in endometrial measurements. The normal myometrium has a homogeneous echotexture, and the sonographer should assess for focal masses, diffuse heterogeneity, distortions in uterine contour, and size. The uterine veins are larger than the arteries and can be identified sonographically as focal anechoic areas around the periphery of the uterus (Fig. 13-7). In older women, atherosclerotic changes within the arcuate arteries of the uterus may be seen as hyperechoic, shadowing foci around the periphery of the uterus (Fig. 13-8). Leiomyomas, also called myomas or fibroids, are benign smooth muscle tumors that develop within the myometrium, but they may intrude into any of the uterine layers (Fig. 13-9). Uterine fibroids represent the most common pelvic tumor and are a leading cause of hysterectomy. Less commonly, fibroids can develop within the vagina, cervix, broad ligament, or fallopian tubes or on the omentum (so-called parasitic fibroids). They are more common in African American women than in women of other ethnicities.3 Fibroids range in size from 1 mm to more than 20 cm. Many women have multiple fibroids of varying sizes. Fibroids are known to grow in response to estrogen stimulation and tend to stabilize or regress during menopause. Fibroids are myometrial in origin, and they can be surrounded by myometrium, intrude into the endometrium, or come in contact with the serosal layer (Fig. 13-10). Fibroids surrounded predominantly by myometrium are the most common and are referred to as intramural fibroids. Fibroids that project into the endometrium are referred to as submucosal fibroids. Subserosal fibroids are in contact with the serosal layer and distort the uterine contour. In some cases, subserosal fibroids grow off of a stalk into the adnexal regions seemingly separate from the uterus; these are referred to as pedunculated fibroids. Generally, only submucosal or large intramural fibroids cause AUB. Pedunculated fibroids are remote from the endometrium and myometrium and typically do not cause menorrhagia. The exact cause of menorrhagia with fibroids is unknown, but fibroid-associated changes in uterine vasculature, contractility, and endometrial surface area may contribute to the problem.4 Fibroids can undergo degeneration, which may cause pain. Medical therapy for uterine fibroids includes birth control pills to reduce menstrual blood loss or short-term use of progestin to treat menorrhagia. Progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are also an option. A more recent treatment for uterine fibroids is uterine artery embolization. For this procedure, a catheter is introduced into the femoral artery and into the uterine artery. Microspheres injected through the catheter undergo embolization and block perfusion of the distal branches of the uterine artery that supply the fibroid, which results in necrosis and shrinkage of the fibroid. MRI-guided focused ultrasound therapy is another recent treatment for fibroids. This treatment involves using focused converging ultrasound beams to generate heat at a focal point causing necrosis of tissue. MRI is used for accurate targeting of the focal point and for monitoring tissue temperatures.4 Submucosal fibroids focally distort the endometrium, creating an area of increased or decreased echogenicity within the endometrium, which may be difficult to differentiate from endometrial polyps. Sonohysterography, the infusion of saline as a contrast agent into the uterine cavity, may help differentiate fibroids from polyps. Generally, submucosal fibroids tend to appear hypoechoic to the secretory endometrium, have a broad base of attachment, and display sonographic evidence of attenuation (Fig. 13-11). Intramural fibroids are relatively easy to visualize when they are hypoechoic and well encapsulated within the myometrium (Fig. 13-12).

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Normal Uterine Anatomy

Normal Sonographic Appearance

Early Proliferative Phase

Periovulatory (Late Proliferative) Phase

Secretory Phase

Postmenopausal (No HRT)

4-8

6-10

7-14

1-4

Myometrial Abnormalities

Leiomyoma

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding