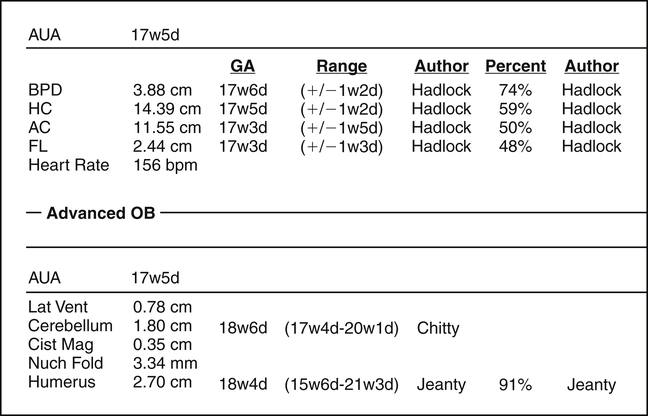

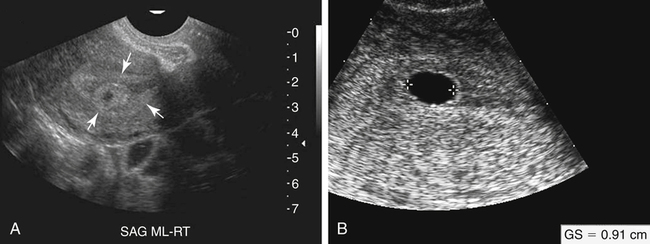

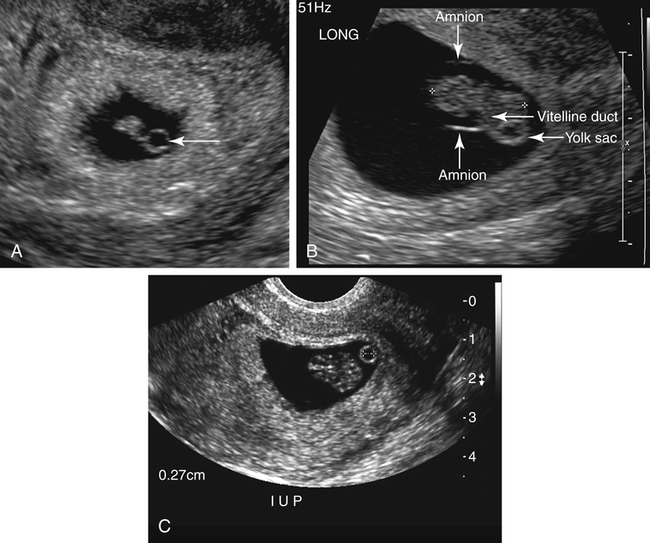

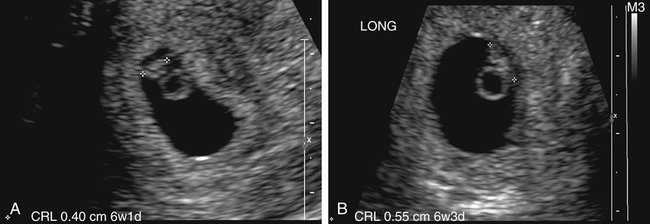

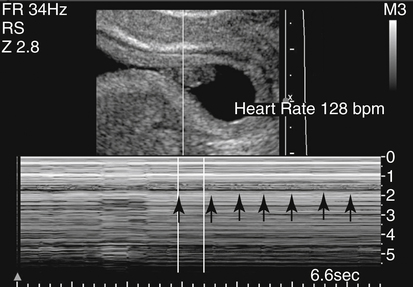

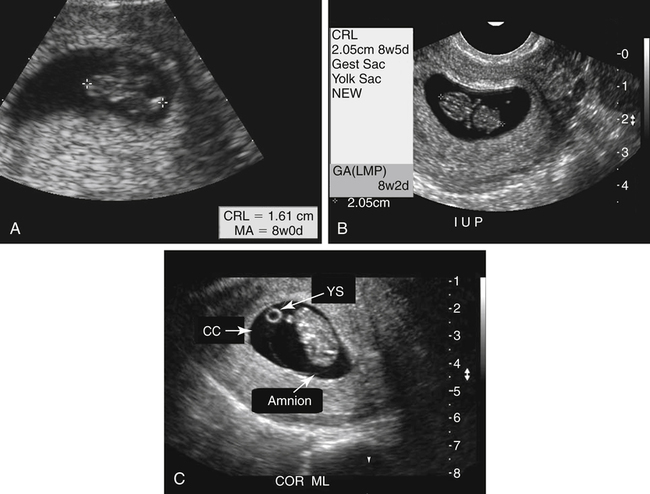

• Describe the purpose of biometric measurements during the first trimester of pregnancy for estimation of gestational age. • Demonstrate appropriate techniques used for accurate first-trimester biometric measurements. • Describe the purpose of biometric measurements during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy for estimation of gestational age. • Demonstrate appropriate techniques used for accurate second-trimester and third-trimester biometric measurements. • Describe additional measurements that may be performed throughout pregnancy for confirmation of gestational age. • Describe additional measurements that may be performed for diagnostic purposes during specific gestational age ranges. • Identify the technical limitations of delayed biometric imaging in cases of uncertain last menstrual period. Before the advent of pregnancy testing and sonography, the LMP was the most identifiable reference point for the beginning of the pregnancy. With advances in prenatal testing, pregnancy is now known to have a duration of approximately 280 days from the first day of the LMP, also referred to as 9 calendar or 10 lunar months. This is also known as Nägele’s rule. In clinical practice, the term “gestational age” is often used interchangeably with “menstrual age,” which dates a pregnancy based on a woman’s LMP. In this chapter, gestational age references are based on LMP. The knowledge of an accurate gestational age is needed to manage the pregnancy optimally; to reduce the risks of preterm and postterm deliveries; and to coordinate elective procedures, such as biochemical screening evaluation, chorionic villus sampling, and amniocentesis, and delivery method, such as a repeat cesarean section or pregnancy induction. Because many women who potentially become pregnant in any given month may have variable cycle lengths, bleeding in early pregnancy, or inaccurate accounts of menstrual dates, estimation of a due date can be a clinical challenge. Patients who seek prenatal care during the first or second trimester of pregnancy without a strong knowledge of LMP or normal cycle lengths may undergo a sonographic examination to estimate gestational age with biometric measurements of the structures of pregnancy or the fetus. Among the measurements that may be obtained for dating purposes during the first trimester using sonographic techniques are the gestational sac diameter and the CRL. First-trimester measurements are considered to be reliable indicators because pathologic states and fetal abnormalities have the least impact on fetal size during this time, and biologic variation is at a minimum during the first few weeks of pregnancy (Box 18-1). The appearance of an anechoic fluid collection surrounded by an echogenic ring in the fundal region of the endometrial cavity is the first sonographic evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (Fig. 18-2, A). This echogenic ring is a vital structure of a normal pregnancy because it represents the chorion and decidua capsularis. Absence of the echogenic ring should prompt suspicion of a pseudogestational sac associated with ectopic pregnancy and may warrant clinical correlation with beta-hCG levels. As the pregnancy progresses and displacement of the endometrial echo occurs, a second outer echogenic ring may be seen that represents the remainder of the endometrial lining, known as the decidua parietalis or decidua vera. The appearance of these two echogenic rings has become known as the double decidual sac sign and may be seen between 4 to 6 weeks of gestational age. The space between the two decidual rings is the unoccupied endometrial cavity, which becomes obliterated as the pregnancy progresses. With two scan planes, a measurement made in each of the three dimensions of the gestational sac can be used to calculate a mean sac diameter (MSD). These sac measurements should be made at the interface between the echogenic border and the fluid (Fig. 18-2, B). The introduction of transvaginal ultrasound techniques has allowed visualization of this normal progression of early pregnancy. With high-frequency transvaginal technique, a pregnancy dating only 4 weeks and 1 or 2 days from the LMP may be visualized as a 2- to 3-mm fluid collection within the uterus. The MSD should correlate closely with suspected gestational age, and any significant variance or suspicion of pregnancy loss should be closely correlated with beta-hCG levels. The MSD is not a true fetal parameter, but its correlation to the estimated gestational age and growth rate may prove to be valuable in the prediction of spontaneous abortion. Normal first-trimester gestational sac growth rate should be approximately 1 mm per day. During this time of rapid embryologic change, a repeat examination may be performed within a few days to show the progression of the pregnancy and confirm it as normal or abnormal. Evidence of a developing intrauterine pregnancy should be seen transvaginally with a serum beta-hCG level greater than 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL using the International Reference Preparation (IRP) standard. The sonographically visualized yolk sac is more accurately called the secondary yolk sac. Most sonographers and sonologists loosely use the term “yolk sac” in discussion of this structure in pregnancy when visualized. The sonographic presence of the yolk sac in an early gestational sac may be considered a predictor of a normally progressing pregnancy before visualization of the embryo. With transvaginal technique, a gestational sac measuring 8 mm or more should demonstrate a yolk sac, which is consistent with a 5 to 5.5-week gestation. The secondary yolk sac appears as a round anechoic structure with an echogenic rim (Fig. 18-3, A). This yolk sac supplies nutrition for the developing embryo through the vitelline duct (Fig. 18-3, B). The size of the yolk sac is most often measured to be 2 to 6 mm throughout the first trimester, and an abnormally small or large measurement may be indicative of pending loss or fetal abnormality. The yolk sac diameter should be measured with placement of calipers along the inner borders of the echogenic ring (Fig. 18-3, C). The yolk sac is also often used to assist in locating the developing embryo. After the yolk sac is located, close evaluation of adjacent structures often identifies the embryonic disk, recognized with the flicker of cardiac activity. After the gestational sac has formed and a yolk sac has developed, the next structure of pregnancy visualized with sonography is the embryo. The embryonic period is considered to be week 6 through week 10 of the pregnancy. In the earliest stage of the embryonic period, the yolk sac may be used as a landmark for locating the very early embryo and possible cardiac activity. Initially, the embryo is found adjacent to the yolk sac and appears on the sonographic image as a flat, disklike structure (Fig. 18-4). Faint flickering of this structure, which represents early cardiac activity, may be seen on real-time sonography at 5.5 weeks or when the CRL measures 5 mm. The normal embryonic heart rate range is 120 to 180 beats per minute. If the embryonic heart rate is 100 beats per minute or less, it should be compared with the maternal heart rate to ensure that maternal uterine vessels are not being sampled and inaccurately represented as embryonic cardiac activity (Fig. 18-5). With transvaginal technique, the embryo should be visualized in a gestational sac that measures 25 mm. Evaluation of the embryo must include multiple scan planes to obtain the longest axis for accurate gestational dating. A measurement of the longest axis, excluding the yolk sac, provides accurate information for estimation of gestational age. This measurement may be difficult because of the small size of the embryo early in the pregnancy. By approximately 8 weeks’ gestational age, the embryo begins to assume a C-shaped appearance, the cystic rhombencephalon can be seen in the posterior embryonic head (Fig. 18-6, A), and limb buds may be apparent (Fig. 18-6, B). At around 11 to 12 weeks, the distinction between the head and torso of the fetus is more easily recognized (Fig. 18-7). An accurate CRL is obtained by placement of the calipers at the top of the fetal head (crown) to the bottom of the torso (rump). Care must be taken not to include the yolk sac or fetal extremities within this measurement. Inclusion of these structures undermines the accuracy of gestational age. Care should also be taken to avoid CRL measurements on an embryo or fetus that is flexed. The final measurement that may be performed during a sonographic examination in the first trimester is not a measurement for gestational age estimation but rather a secondary measurement and early screening tool for possible fetal aneuploidy. The nuchal translucency (NT) refers to the normal subcutaneous translucent space along the back of the fetal neck. The thickness of this space has been the source of numerous studies. A thickened NT is associated with fetal aneuploidy, most specifically trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). Increased NT thickness is also associated with genetic syndromes, structural anomalies, and adverse outcome.1 Techniques for measurement of the NT require accuracy and precision in the sonographic view, caliper placement, and gestational age at the time of imaging. To assess NT thickness, the true sagittal plane of the embryo must be acquired. The appropriate technique for measurement of the NT involves placement of the calipers at the fetal skin and the posterior aspect of the nuchal membrane (Fig. 18-8). This technique must be performed with precision because spaces of this small size can be misinterpreted as abnormal with even the slightest variation. The amnion is often found along the posterior edge of the fetus. With the fetus in the supine position, the amniotic cavity behind the fetus may be confused as the NT and measured as abnormally thickened. Sonographer training and experience in this technique are important to prevent inaccurate measurements that may create false-positive results.

Uncertain Last Menstrual Period

First-Trimester Biometry

Gestational Sac

Yolk Sac

Crown-Rump Length

Nuchal Translucency

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Uncertain Last Menstrual Period