9 Abscesses Mastitis can be classified according to whether or not it occurs during the special hormonal environment of pregnancy or lactation (Table 9.1). The mammary ducts provide a hospitable environment for microorganisms, which enter most commonly through a fissured nipple, and bacterial inflammation is particularly common during lactation. The majority of these infections are staphylococcal. Bacterial mastitis, a breast cellulitis, can be further characterized as an acute inflammation or as a more advanced process that has matured to abscess formation. The time of diagnosis has major clinical implications for treatment. A florid inflammatory process marked by redness and breast edema without liquefaction responds well to antibiotic therapy, especially when supported by antibiotics such as amoxicillin or clindamycin, anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, and frequent breast-feeding or pumping to keep the breast empty. If the symptoms are communicated to the obstetrician as soon as they become evident, antibiotic therapy may forestall development of an abscess. Ultrasound is indicated for evaluation of patients with mastitis to confirm or exclude an underlying abscess. Once abscess formation has occurred, the lesion must be drained. The drainage procedure, which may be done with ultrasound guidance or surgically, may be preceded by heat application to promote liquefaction and demarcation of the suppurative focus (Table 9.2).

Clinical Significance

Lactational Abscesses

|

|

– e. g., tuberculosis

|

– Granulating – Immunologic

– Granulomas – Cysts, ducts, or wound area |

Acute inflammation | Liquefaction |

Antibiotics | Surgical percutaneous drainage* |

Anti-inflammatory agents (local or systemic) | Aspiration (if appropriate), with or without catheter insertion for drainage and irrigation |

Dopamine agonists | |

Specialized treatment as in granulomatous sarcoidosis (cortisone) | |

* Gram stain, bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity

Nonpuerperal Abscesses

Mastitis and abscess can occur at any age. Inflammatory processes may involve the entire breast or only a small segment. Cysts are sometimes affected by inflammation, which usually resolve following aspiration and complete drainage of the purulent material Although many cysts that contain low-level internal echoes are clinically insignificant, infected cysts are symptomatic with pain and sometimes redness and warmth to the touch. If they are accompanied by systemic signs such as leukocytosis, fever, or an elevated C reactive protein (CRP), antibiotics should be administered, although ultrasound-guided aspiration of the cyst contents may bring prompt relief.

Women of any age who are immunosuppressed, diabetic, or have had significant trauma or previous breast surgery including major duct excisions, may develop abscesses or infected hematomas or seromas. Mastitis and abscess in these women are diagnosed and treated as for puerperal inflammatory processes. Additional sites of inflammatory processes are in the axilla, where infected hair follicles or sebaceous glands can result in drainable collections, or the areola where small infected pockets may involve the glands of Montgomery. In men inflammatory processes occur less commonly, but infected epidermal inclusion cysts near the nipple may result in a cancer-mimicking breast mass.

In older women, or any adult woman, particularly if the inflammatory process is nonlactational, the most important distinction to be made is mastitis and abscess vs. inflammatory carcinoma. The first step in the management sequence is antibiotic therapy (although inflammatory carcinoma also may show some response initially). Once abscess has been excluded and, if present, treated, and if there is incomplete resolution after the entire antibiotic course, mammography and ultrasound should be performed, with core biopsy of any solid masses found with ultrasound for histology—most often poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma—and a punch biopsy of the thickened skin expecting to find tumor emboli in the subdermal lymphatics. The primary treatment of inflammatory carcinoma is chemotherapy, and if a tumor infiltrate is not found in the lymphatics, treatment will still be for inflammatory carcinoma based on the clinical presentation.

The nipple area may become acutely inflamed as a result of infected juvenile cysts with retained secretions in the ducts. A careful, tissue-conserving approach is warranted in these cases to avoid damage to the breast bud by spreading inflammation or excessive surgical manipulation. With the abundant blood supply to juvenile tissue, it is generally sufficient to do a single aspiration and provide supportive antibiotics. In older women, inflamed or ulcerated nipples (not areolae) can signify Paget disease, ductal carcinoma in situ involving the large ducts nearing and in the nipple. Invasive carcinoma may also be present.

Immune responses can also lead to chronic mastitis conditions, which may be diffuse or may take the form of focal inflammatory nodules and granulomas as in erythema nodosum or sarcoidosis (Boeck disease). Chronic granulomatous mastitis, of noninfectious but unclear etiology, can mimic invasive lobular carcinoma on ultrasound. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy can provide the diagnosis, and biopsy is indicated. Foreign-body reactions (e. g., to implantation of a prosthesis) can also incite mastitis.

Diagnostic Criteria

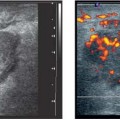

Edema

Acute mastitis is initially characterized by increased fluid accumulation in the breast tissue. Initially, the parenchyma becomes more diffusely hypoechoic, but the glandular structures can still be discerned. With the onset of abscess formation, the tissue becomes increasingly hypoechoic toward the center of the focus (Fig. 9.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

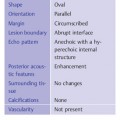

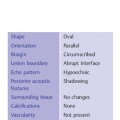

Puerperal

Puerperal Nonpuerperal

Nonpuerperal Bacterial

Bacterial Specific

Specific Acute

Acute Diffuse

Diffuse Abacterial

Abacterial Suppurative, chronic recurring

Suppurative, chronic recurring Focal

Focal