Etiology

Peritoneal inclusion cysts develop from peritoneal adhesions trapping fluid, often generated from an active ovary. The normal peritoneum absorbs fluid regularly. When the peritoneum is injured, as can occur with surgery, infection, or endometriosis, normal fluid absorption is hampered. This results in fluid accumulation within adhesions or peritoneal inclusion cysts. Reportedly at least 70% of all patients with peritoneal inclusion cysts in one study had a known prior peritoneal insult.

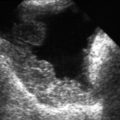

Ultrasound Findings

Peritoneal inclusion cysts are multilocular, cystic masses that conform to the shape of the peritoneum and surrounding organs. They appear as multicystic, septate adnexal or cul-de-sac masses that can be small or attain large sizes. The septations can be thick or thin and can be multiple as the “mass” insinuates itself in the crevices of the pelvic side wall. Often a normal-appearing ovary can be identified embedded along the edges of the mass as the ovary is usually trapped in the web of adhesions but not actually part of the peritoneal inclusion cyst itself.

Differential Diagnosis

Peritoneal inclusion cysts are easily confused with other complex cystic and septate adnexal masses. These include hydrosalpinx, paraovarian cyst, or ovarian neoplasm such as a cystadenoma. In the setting of prior pelvic surgery, the correct diagnosis of peritoneal inclusion cysts can be made, especially if a normal-appearing ovary is seen trapped in the edge of the cyst and the cyst conforms to the shape of the adjacent peritoneal cavity.

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Because peritoneal inclusion cysts are virtually always a form of adhesive disease, many of these patients complain of pain, especially with activity such as intercourse, exercise, or bowel movements. This is especially true in those patients whose adhesions are secondary to pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, or possibly, although less likely, previous pelvic surgery. Many peritoneal inclusion cysts, however, are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during imaging. Because of the variable nature of their sonographic appearance, such “masses” may occasionally appear concerning, and surgical exploration may be undertaken. If such masses are clearly recognized as peritoneal inclusion cysts and are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, conservative therapy is appropriate. In most patients with significant pain, surgical correction with lysis of adhesions may be appropriate, although the risk of recurrence is approximately 30% to 50% after surgical treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree