Airways Disease

Jeffrey S. Klein

Trachea and Central Bronchi

Congenital Tracheal Anomalies

Tracheal agenesis, cartilaginous abnormalities of the trachea, tracheal webs and stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistulas, and vascular rings and slings present as breathing and feeding difficulties in the neonatal and infancy period. These are uncommon congenital lesions that are discussed in Chapter 50.

Tracheoceles, also known as paratracheal air cysts, are true diverticula that represent herniation of the tracheal air column through a weakened posterior tracheal membrane. These lesions occur almost exclusively in the cervical trachea because the pressure gradient from the extrathoracic trachea to the atmosphere with the Valsalva maneuver favors their formation in this region. Tracheoceles are usually asymptomatic and are easily recognized on CT as circular lucencies along the right posterolateral trachea at the thoracic inlet.

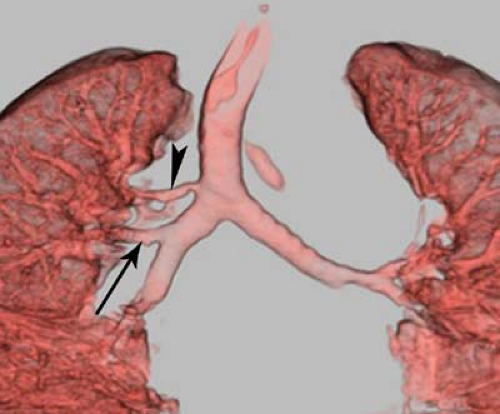

Tracheal bronchus or bronchus suis, so called because it is the normal pattern of tracheal branching in pigs, consists of an accessory bronchus to all or a portion of the right upper lobe that arises from the right lateral tracheal wall within 2 cm of the tracheal carina (Fig. 18.1). However, it most often supplies the apical segment of the right upper lobe. While it is usually an incidental finding on chest CT in 0.5% to 1.0% of the population, there is an association with congenital tracheal stenosis and an aberrant left PA. Most patients are asymptomatic.

Focal Tracheal Disease

Focal disorders of the trachea may produce narrowing or dilatation of the tracheal lumen (Table 18.1) (1). Focal narrowing may be produced by extrinsic or intrinsic mass lesions, retraction, or inflammatory disorders of the tracheal wall.

Extrinsic Mass Effect. The most common cause of extrinsic mass effect on the trachea is a tortuous or dilated aortic arch or brachiocephalic artery, typically seen in older individuals as a rightward deviation of the distal trachea. An intrathoracic goiter or a large paratracheal lymph node mass is an additional cause of extrinsic tracheal mass effect. Extrinsic mass effect can also be seen with congenital vascular anomalies, such as an aberrant left pulmonary artery and aortic ring, or with a large mediastinal bronchogenic cyst. Because the tracheal cartilage provides resiliency, extrinsic masses tend to displace the trachea without narrowing its lumen. Traction deformity of the trachea is generally seen in cicatrizing processes that asymmetrically affect the lung apices, most commonly postprimary tuberculosis (TB), histoplasmosis, and radiation fibrosis. Occasionally the distal trachea is narrowed in patients with sclerosing mediastinitis, although this disorder normally affects the central bronchi.

Focal Tracheal Stenosis. Focal tracheal or central (main and proximal lobar) bronchial narrowing may result from inflammatory disorders that affect the tracheal or central bronchial walls. Cartilaginous damage or the development of granulation tissue and fibrosis from a tracheostomy or at the site of a previously inflated endotracheal tube balloon cuff can lead to focal tracheal narrowing (Fig. 18.2). The tracheal stenosis has a typical hourglass deformity on frontal radiographs. Those patients with tracheomalacia from cartilage damage may manifest narrowing only during phases of the respiratory cycle when extratracheal pressure exceeds intratracheal pressure. Therefore, patients with extrathoracic tracheomalacia, most often at the site of a prior tracheostomy, demonstrate tracheal narrowing on inspiration, whereas patients with intrathoracic tracheomalacia, usually from prior endotracheal intubation, have tracheal narrowing on expiration. Postintubation stenosis is rare with the low-pressure, high-volume endotracheal tube cuffs in current use. Wegener’s granulomatosis can produce a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the trachea and central bronchi, leading to focal cervical tracheal narrowing or, in advanced disease, narrowing of the entire length of the trachea. The diagnosis of tracheal involvement by Wegener granulomatosis is made by the radiographic demonstration of tracheal narrowing in association with upper airway and renal involvement and characteristic findings on biopsy. Cyclophosphamide therapy administered early in the course of the disease may reduce inflammation and improve tracheal narrowing. Sarcoidosis involving the central airways may rarely cause focal tracheal or bronchial stenosis.

A number of infectious processes may result in tracheal or bronchial inflammation and stenosis. Endotracheal and endobronchial TB is usually associated with cavitary TB, where the production of large volumes of infected sputum predisposes

to tracheal and central bronchial infection. Upper tracheal inflammation and stenosis may result from histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis. Invasive tracheobronchitis from aspergillosis, candidiasis, and mucormycosis has been described in immunocompromised patients. Tracheal scleroma is a chronic granulomatous disorder caused by infection with Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. This disease is uncommon in the United States and is seen most commonly in people of lower socioeconomic standing in Central and South America and Eastern Europe. The infection begins as an inflammation of the nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses, extending inferiorly to involve the larynx, pharynx, and trachea in a minority of patients. In its chronic phase, intense granulation tissue and fibrosis lead to stenosis of the nasal cavity, pharynx, larynx, and upper trachea; the latter is seen in fewer than 10% of patients. Radiographically, the upper trachea shows irregular nodular narrowing, which may extend to involve the length of the trachea. The diagnosis is made on biopsy, which reveals granulation tissue containing large foamy histiocytes filled with the causative organism (Mikulicz cells). Antibiotic treatment is effective if administered in the early phases of infection before extensive fibrosis has developed.

to tracheal and central bronchial infection. Upper tracheal inflammation and stenosis may result from histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis. Invasive tracheobronchitis from aspergillosis, candidiasis, and mucormycosis has been described in immunocompromised patients. Tracheal scleroma is a chronic granulomatous disorder caused by infection with Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. This disease is uncommon in the United States and is seen most commonly in people of lower socioeconomic standing in Central and South America and Eastern Europe. The infection begins as an inflammation of the nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses, extending inferiorly to involve the larynx, pharynx, and trachea in a minority of patients. In its chronic phase, intense granulation tissue and fibrosis lead to stenosis of the nasal cavity, pharynx, larynx, and upper trachea; the latter is seen in fewer than 10% of patients. Radiographically, the upper trachea shows irregular nodular narrowing, which may extend to involve the length of the trachea. The diagnosis is made on biopsy, which reveals granulation tissue containing large foamy histiocytes filled with the causative organism (Mikulicz cells). Antibiotic treatment is effective if administered in the early phases of infection before extensive fibrosis has developed.

Tracheal and bronchial masses are mostly neoplasms and are discussed in Chapter 15.

Focal tracheal dilatation is caused by congenital or acquired abnormalities of the elastic membrane or cartilaginous rings of the trachea. Localized tracheal dilatation may be seen with tracheoceles, with acquired tracheomalacia related to prolonged endotracheal intubation, or as a result of tracheal traction from severe unilateral upper lobe parenchymal scarring.

Diffuse Tracheal Disease

Diffuse disorders of the trachea manifest as either narrowing or dilatation of the tracheal lumen. Diffuse tracheal narrowing may be seen with saber-sheath trachea, amyloidosis, tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, relapsing polychondritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, or tracheal scleroma (Table 18.2) (2). The latter two conditions may cause diffuse tracheal narrowing, but more commonly the involvement is limited to the cervical trachea. These conditions are discussed in the section on focal tracheal narrowing.

Table 18.1 Causes of Focal Tracheal Disease | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diffuse Tracheal Narrowing

Congenital tracheal stenosis is a rare condition in which there is incomplete septation of the cartilage rings, producing a long segment tracheal narrowing or “napkin ring” trachea. This anomaly is often associated with other congenital cardiovascular anomalies, in particular anomalous origin of the left PA from the right PA (“PA sling”) and anomalous origin of the right upper lobe bronchus from the trachea (“tracheal bronchus” or “bronchus suis”).

Saber-sheath trachea is a fixed deformity of the intrathoracic trachea in which the coronal diameter is diminished to less than two-thirds of the sagittal diameter. The tracheal wall is uniformly thickened, and calcification of the cartilaginous rings is present in most cases. This entity exclusively affects older men with functional evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The tracheal narrowing likely reflects the chronic transmission of increased intrapleural pressure seen in obstructive lung disease and tracheal injury from chronic cough. The characteristic findings are apparent on frontal radiographs and CT (Fig. 18.3).

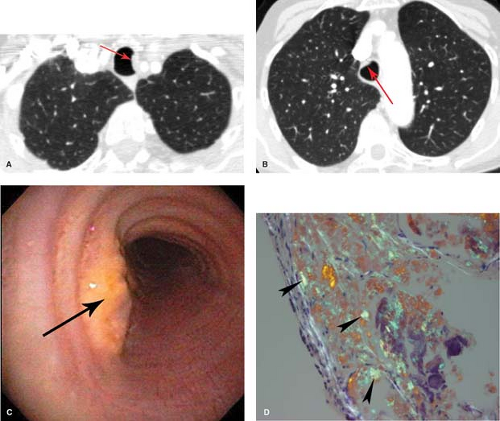

Amyloidosis is characterized by the deposition of a fibrillar protein–polysaccharide complex in various organs. It may involve the airways as part of localized or systemic disease. Submucosal deposits in the tracheobronchial tree are more commonly a manifestation of localized disease and may be associated with nodular or alveolar septal deposits in the lungs. Mass-like circumferential deposits that irregularly narrow the tracheal lumen are best demonstrated on CT and can result in recurrent atelectasis and pneumonia. Calcification of these deposits occurs in only 10% of cases. The diagnosis is made by the presence of typical protein–polysaccharide deposits demonstrated following Congo red staining of tracheal or bronchial wall biopsy specimens. This typically demonstrates apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light (Fig. 18.4).

Table 18.2 Causes of Diffuse Tracheal Disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

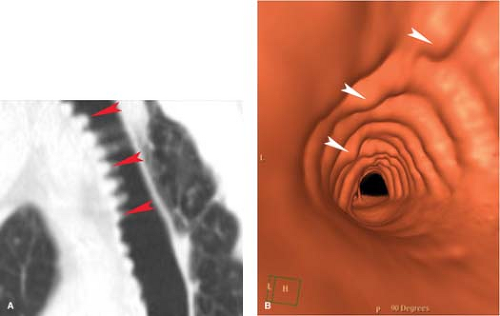

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is a rare disorder characterized by the presence of multiple submucosal osseous and cartilaginous deposits within the trachea and central bronchi of elderly men. The lesions arise as enchondromas from the tracheal and bronchial cartilage, and then project internally to produce nodular submucosal deposits that irregularly narrow the tracheal lumen and have a characteristic

appearance and feel on bronchoscopy. The diagnosis is generally made on bronchoscopy and CT, where calcified plaques can be seen involving the anterior and lateral walls of the trachea. Sparing of the membranous posterior wall of the trachea, which lacks cartilage, is a helpful feature that distinguishes this entity from tracheobronchial amyloid (Fig. 18.5). While usually asymptomatic, patients may have recurrent infection related to bronchial obstruction by the masses.

appearance and feel on bronchoscopy. The diagnosis is generally made on bronchoscopy and CT, where calcified plaques can be seen involving the anterior and lateral walls of the trachea. Sparing of the membranous posterior wall of the trachea, which lacks cartilage, is a helpful feature that distinguishes this entity from tracheobronchial amyloid (Fig. 18.5). While usually asymptomatic, patients may have recurrent infection related to bronchial obstruction by the masses.

Relapsing polychondritis is a systemic autoimmune disorder that commonly affects the cartilage of the earlobes, nose, larynx, tracheobronchial tree, joints, and large elastic arteries. Early in the disease, tracheal wall inflammation associated with cartilage destruction leads to an abnormally compliant and dilated trachea. Later in the disease, fibrosis leads to diffuse fixed narrowing of the tracheal lumen. Respiratory complications secondary to involvement of the upper airway cartilage accounts for nearly 50% of all deaths from this condition. The diagnosis is made by noting recurrent inflammation at two or more cartilaginous sites, most commonly the pinnae of the ear (producing cauliflower ears) and the bridge of the nose (producing a saddlenose deformity). Radiographs and CT show diffuse smooth thickening of the wall of the trachea and central bronchi with narrowing of the lumen.

Diffuse Tracheal Dilatation

Tracheobronchomegaly (Mounier–Kuhn syndrome) is a congenital disorder of the elastic and smooth muscle components of the tracheal wall. An association with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, a congenital defect in collagen synthesis, and cutis laxa, a congenital defect in elastic tissue, has been reported. The disease is found almost exclusively in men under the age of 50. Abnormal compliance of the trachea and central bronchi leads to central bronchial collapse during coughing. The airways obstruction impairs mucociliary clearance, predisposing the patient to recurrent episodes of pneumonia and bronchiectasis. Symptoms are indistinguishable from those associated with chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis. On frontal radiographs, the trachea and central bronchi measure greater than 3.0 cm and 2.5 cm, respectively, in coronal diameter. The trachea has a corrugated appearance caused by the herniation of tracheal mucosa and

submucosa between the tracheal cartilages (Fig. 18.6). The lungs are typically hyperinflated and may demonstrate bullae.

submucosa between the tracheal cartilages (Fig. 18.6). The lungs are typically hyperinflated and may demonstrate bullae.

Tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) with diffuse tracheal and central bronchial dilatation may result from a congenital or acquired defect of tracheal cartilage (3). Congenital disorders most often associated with TBM include relapsing polychondritis, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and mucopolysaccharidosis. Acquired TBM is more common than the congenital form and is most often the result of prolonged intubation, prior tracheostomy, and extrinsic tracheal compression by mediastinal masses and vascular anomalies. Symptoms and radiographic findings are similar to those of tracheobronchomegaly-cough, dyspnea, wheezing, and recurrent respiratory infection. The imaging hallmark of tracheomalacia is excessive airway collapse on expiration, seen best on CT performed at total lung capacity (i.e., inspiration) in comparison to dynamic expiratory CT with a low-dose CT acquisition performed during a forced expiratory maneuver. A reduction in the cross-sectional area of the trachea exceeding 50% on the expiratory CT, particularly if there is a crescentic “frown-like” configuration to the trachea in cross section, is strongly suggestive of the diagnosis (Fig. 18.7).

In some patients with long-standing interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, diffuse tracheal dilatation may be seen. The etiology of the tracheal dilatation may relate to long-standing elevation in transpulmonary pressures caused by diminished lung compliance or to chronic coughing.

Tracheal and Bronchial Injury

Injury to the trachea or main bronchi is most often seen with blunt chest trauma from a deceleration-type injury. Concomitant aortic laceration, great vessel injury, or rib (particularly an upper anterior rib), sternum, scapula, or vertebral fracture is the rule and may dominate the clinical picture. The mechanism of injury is forceful compression of the central tracheobronchial tree against the thoracic spine during impact. The fractures generally involve the proximal main bronchi (80%) or distal trachea (15%) within 2 cm of the tracheal carina; the peripheral bronchi are involved in 5% of cases. Horizontal laceration or transection parallel to the tracheobronchial cartilage is the most common form of injury.

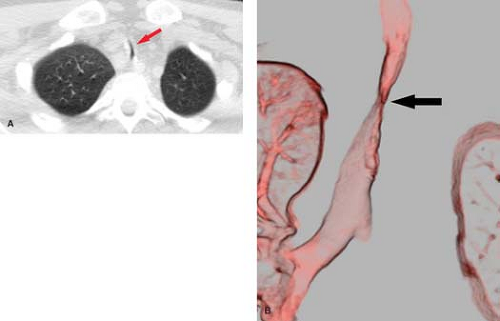

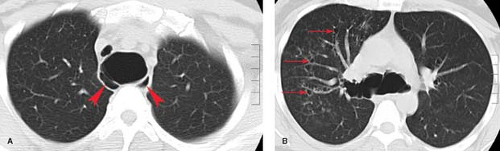

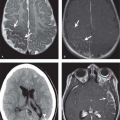

The diagnosis of tracheobronchial injury is often first suggested on early post-trauma chest radiographs by the presence of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum, particularly in a patient not receiving mechanical ventilation (Fig. 18.8A). Typically, the pneumothorax fails to respond to chest tube drainage owing to a large air leak at the site of airway interruption. The subtended lung remains collapsed against the lateral chest wall (“fallen lung” sign) (Fig. 18.8B). An aberrant endotracheal tube or an overdistended balloon cuff is a further clue to the presence of an unsuspected tracheobronchial disruption. As many as one third of tracheobronchial injuries have a delayed diagnosis; these patients may present with a collapsed lung or pneumonia secondary to bronchial stenosis. Definitive diagnosis is by bronchoscopy. MDCT with three-dimensional reconstruction with shaded surface display may be useful in patients who develop bronchial occlusion or stenosis because of a delay in diagnosis.

Penetrating tracheal injuries usually involve the cervical trachea and result from gunshot or stab wounds to the neck. Injury to the intrathoracic trachea is usually associated with fatal penetrating cardiovascular injury.

Broncholithiasis

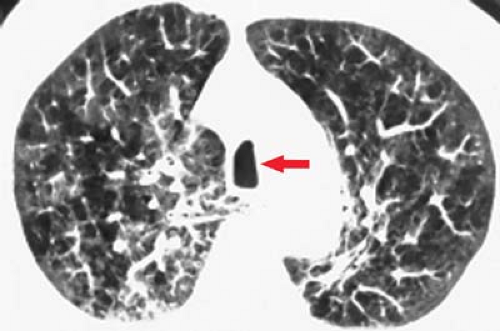

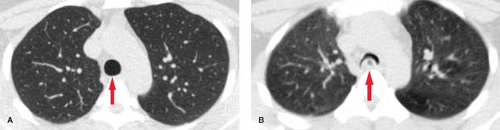

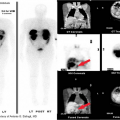

Broncholithiasis, the presence of calcified material within the tracheobronchial tree, develops from erosion of a calcified peribronchial lymph node into the bronchial lumen (Fig. 18.9). Most calcified lymph nodes result from granulomatous lymph node inflammation caused by histoplasmosis or TB. Broncholiths may occlude the airway and lead to bronchiectasis, obstructive atelectasis, or pneumonia. Patients are often asymptomatic but

may have cough productive of stones or calcified material (lithoptysis). Hemoptysis may develop from erosion of the broncholith into a bronchial vessel.

may have cough productive of stones or calcified material (lithoptysis). Hemoptysis may develop from erosion of the broncholith into a bronchial vessel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree