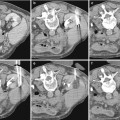

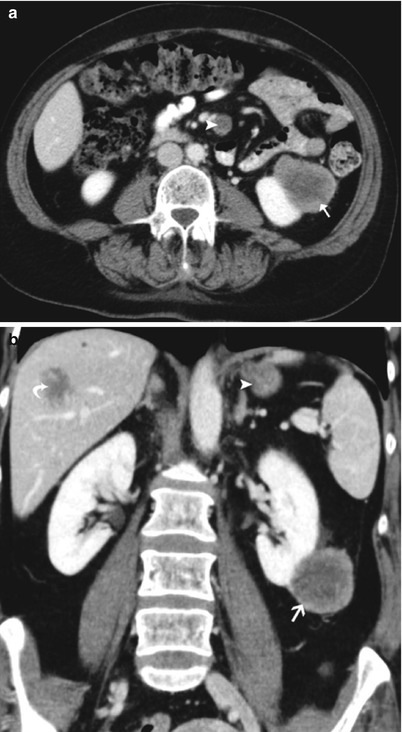

Fig. 1

Renal metastases from a spinocellular carcinoma of the lung in a 68-year-old woman. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows two hypodense renal metastases in the left kidney (arrows). (b, c) FDG-PET shows increased FDG uptake in the left renal metastasis (small arrow) and in the primary spinocellular carcinoma at the right lung hilum (large arrow)

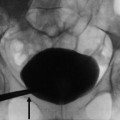

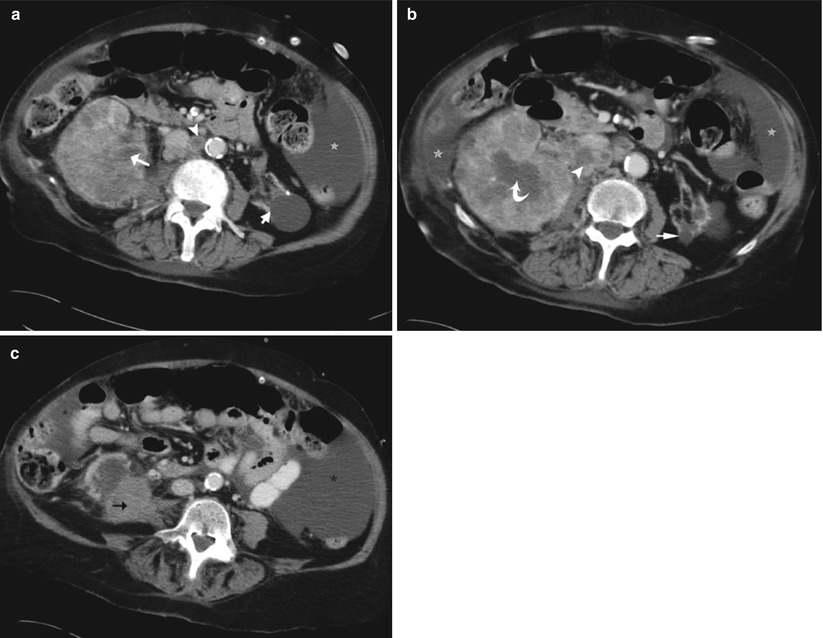

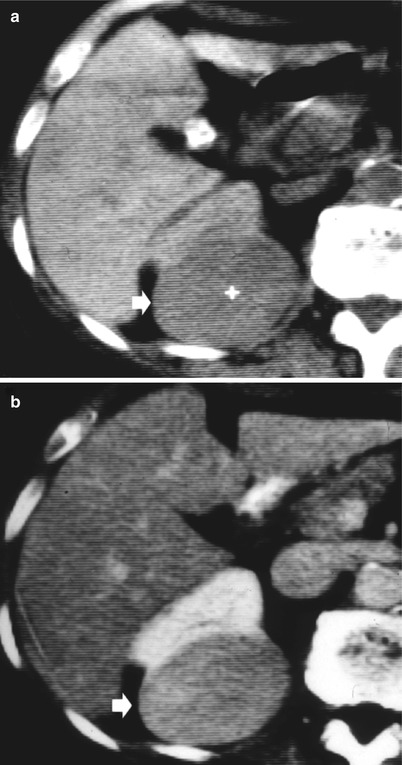

Fig. 2

Renal, liver, and mesenterial metastases from a malignant melanoma in a 53-year-old woman. Axial (a) and coronal (b) images of a contrast-enhanced CT scan in the parenchymal phase show the well-delineated exophytic hypodense mass in the left kidney, extending in the perirenal space (arrow). Similar masses in the liver (metastases – curved arrow) and in the mesentery (lymph node metastases – arrowhead)

1.2 Imaging Features and Differential Diagnosis

Renal metastases are more likely to have an expansile growth pattern, while infiltrative growth pattern is highly uncommon (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

The most frequent imaging feature is that of multiple small bilateral, intracortical mass lesions, with a vascularity similar to the primary tumor. Less than 2 % of renal cell carcinomas (RCC) have a similar imaging pattern. Furthermore, this resembles the most frequent presentation form of the rare renal malignant lymphoma (Choyke et al. 1987; Sheth et al. 2006).

The aspect of the lesions mostly depends on the aspect of the primary tumor. Most renal metastases are hypovascular at contrast-enhanced CT. Intravenous contrast administration is essential because on unenhanced CT, intracortical renal metastases may have similar attenuation as the parenchyma and often cause no deformation of the renal outline (Choyke et al. 1987). Metastases of colon carcinoma tend to be large and exophytic masses, while metastases of malignant melanoma and lung cancer tend to extend into the perirenal space (Choyke et al. 1987; Heller et al. 2012).

Both multifocal hypovascular RCC (papillary carcinoma) and renal lymphoma are rare. Especially in patients with a known primary tumor, multiple mass lesions are highly suspicious for renal metastases. If no primary tumor is known, imaging-guided biopsy is indicated to differentiate between surgical lesions (i.e., RCC) and nonsurgical lesions (renal metastases and lymphoma). This is a well-accepted indication for targeted percutaneous imaging-guided lesion biopsy.

High-density cysts may be difficult to differentiate from hypovascular mass lesions on routine staging CT. With dedicated techniques, including targeted renal ultrasonography, CT, or MRI, appropriate differentiation between high-density cysts and hypovascular masses can be achieved.

Diagnostic problems occur when metastases present as a solitary renal mass. In patients with advanced metastatic disease, a (newly discovered) solitary renal mass is more likely to be metastatic. In patients with tumoral remission, a solitary renal mass is problematic and percutaneous imaging-guided biopsy is required for further diagnostic and therapeutic management (Choyke et al. 1987).

2 Other Rare Renal Tumors

2.1 Medullary Tumors

Malignant medullary tumors account for 1–2 % of malignant renal tumors (Pickhardt et al. 2000). They are classified in a separate subgroup than the primary malignant renal epithelial tumors of the renal cortex and pelvis. The pathogenesis of these tumors is uncertain, and it is not yet obvious whether they are related (Srigley and Eble 1998).

2.1.1 Collecting (Bellini) Duct Carcinoma (CDC)

General Features and Pathogenesis

Of all renal carcinomas, 0.6–1.3 % are collecting duct carcinomas (CDC) (Chao et al. 2002). Old reports refer to these tumors as Bellini duct carcinoma as it was hypothesized that they arose from the ducts of Bellini (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

CDC was for a long time considered as a subtype of the RCC arising from the distal tubule/collecting duct, like chromophobic RCC and oncocytoma RCC (Störkel et al. 1997).

Because CDC’s radiological, clinical, and immunohistochemical appearance is completely different from RCC and, in addition, due to the resemblance with the behavior of urothelial carcinoma (transitional cell carcinoma, TCC), a recent study of Orsola et al. (2005) suggests an association of CDC with TCC. This can be explained by the common embryologic origin (branching of mesonephric duct) of collecting ducts and urothelial cells. This hypothesis is not yet confirmed since studies on CDC are limited due to their rarity.

The range of age at presentation is wide with a mean age of 55 years. There is a male predominance of 2:1 (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Clinical presentation of CDC is similar to that of other renal carcinomas: hematuria, flank pain, and palpable mass. Prognosis is very poor as the tumor has an aggressive behavior with early metastases (Pickhardt et al. 2000). CDC spreads to the regional lymph nodes (60–80 %), lung or adrenal glands (25 %), bone, and liver (Yoon and Rha 2006).

Imaging Features and Differential Diagnosis

CDC is somewhat arbitrarily classified into three types according to their predominant location: medullary location, medullary location with cortical extension, and medullary location with renal sinus extension (Yoon and Rha 2006).

At the time of discovery or presentation, the tumor is often bulky and usually cortical and sinus extension is present.

CDC has an infiltrative growth pattern, but sometimes presents with a concomitant expansile component (Fig. 3). On imaging studies, the tumor is ill-defined due to infiltrative growth pattern in some areas, while it can present as a well-defined mass in other areas due to the presence of a concomitant expansile component (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

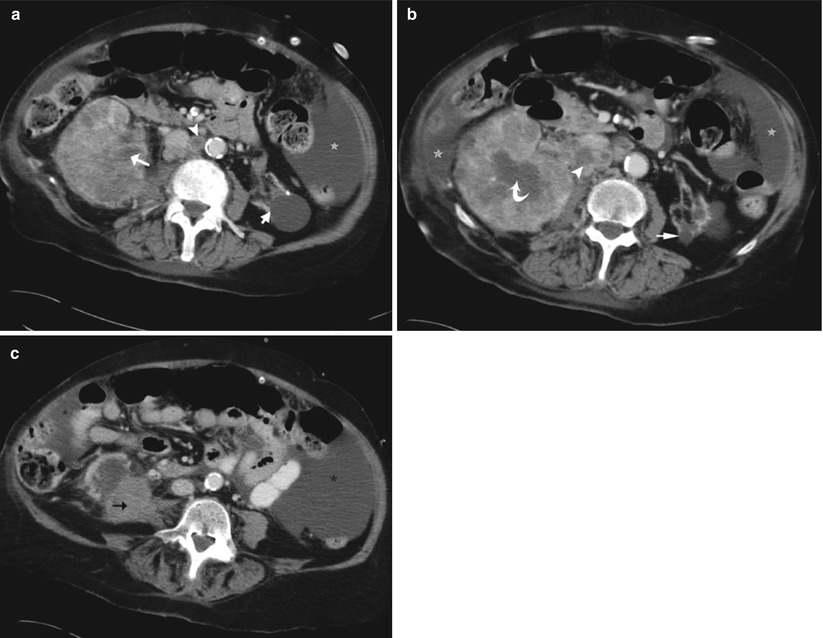

Fig. 3

Collecting duct tumor in a 76-year-old woman. Axial images (a–c) of a contrast-enhanced CT scan in the parenchymal phase show a large infiltrative, centrally located right renal mass, with diffuse infiltration in the renal cortex and invasion in the renal sinus (white arrow). Presence of hypoattenuating areas (curved arrow) in the tumoral mass due to desmoplastic reaction. There is expansile growth in the right lower pole (black arrow). Note also the necrotic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies (arrowhead), the widespread ascites (asterisk), and the left atrophic kidney (short arrow)

Extension in the perirenal space and vascular invasion are not infrequent. Calcification is rarely present. Intralesional cyst-like areas are frequently encountered, sometimes due to tumor necrosis (Yoon and Rha 2006). Rarely, CDC presents with several satellite cortical nodules (Mejean et al. 2003).

On ultrasound, CDC is usually almost isoechoic to the renal parenchyma. On CT scan, the tumoral mass is hypovascular with avascular areas. These avascular areas are explained by the extensive desmoplastic reaction rather than necrosis.

On T2-weighted MRI, the tumoral mass is hypointense and isointense on T1-weighted images. T2 hypointensity combined with medullary location of the lesion favors the diagnosis of CDC (Yoon and Rha 2006). Similar to CT, the tumor is hypovascular with avascular desmoplastic areas.

Undifferentiated TCC may have an infiltrative growth pattern, and differential diagnosis can be impossible based on imaging studies.

More central location favors the diagnosis of CDC or invasive TCC. Distinguishing these tumors preoperatively is important as TCC requires a nephroureterectomy rather than a (radical) nephrectomy. If preoperative histological analysis is uncertain, nephroureterectomy needs to be performed as TCC is much more frequent than CDC (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Other differential diagnosis includes infiltrative forms of renal metastasis and lymphoma. Clinical history is contributive to resolve this differential diagnosis.

2.1.2 Renal Medullary Carcinoma

General Features

By reviewing renal pelvic carcinomas of the database of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in 1995, this new variant of CDC associated with sickle cell trait (SCT) was described (Davis et al. 1995). Yet, sickle cell anemia (SCA) is surprisingly not associated with this subtype. SCT or sickle cell carrier (HbSA and HbSC) is much more common than sickle cell disease/anemia but can be clinically occult (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Generally, six nephropathies were associated with SCT and SCA: macroscopic hematuria, papillary necrosis, nephrotic syndrome, renal infarction, failure to concentrate urine, and pyelonephritis. Renal medullary carcinoma is added as the seventh nephropathy by Davis et al. (1995) and Warren et al. (1999).

The hypothesis for the relation between medullary carcinoma and SCT is that chronic hypoxia in the renal medulla secondary to the SCT may initiate transitional cell proliferation of the distal collecting ducts and papillary epithelium (Prasad et al. 2005).

This tumor occurs in young patients with an age span between 11 and 39 years. Between 11 and 24 years of age, there is a male predominance, and beyond 24 years of age, gender predominance is no longer present (Davis et al. 1995). The right kidney seems to be more often affected (Leitão et al. 2006).

Clinical presentation is similar to that of other renal carcinomas and includes hematuria, flank pain, and palpable mass (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Gross hematuria is a common finding in patients with SCT and is usually self-limiting and painless. Even though it is commonly seen in patients with SCT without the presence of a tumor, this symptom should alert the clinician and radiologist to screen these patients for the presence of a renal tumor (Blitman et al. 2005).

The prognosis is very poor as in CDC, since the tumor has an extremely aggressive biological behavior with early metastases to the regional lymph nodes, liver, and lungs (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Imaging Features and Differential Diagnosis

Reported renal medullary carcinoma shows an infiltrative growth pattern. They are centrally located and can cause pelvic encasement. Sometimes smaller satellite lesions are present in the cortex or hilum (Prasad et al. 2005). Hemorrhage and necrosis are frequently observed. Hydrocalyces (oncocalyces) without dilatation of the renal pelvis is an associated finding (Blitman et al. 2005; Pickhardt et al. 2000).

The differential diagnosis includes all invasive infiltrative tumoral lesions including TCC, RCC, renal metastases, lymphoma, and CDC (Davidson et al. 1995).

CDC is more often seen in adults and is not associated with a SCT. However, some pathologists suggest that renal medullary carcinoma is an aggressive form of CDC (Blitman et al. 2005).

Race (often black race), age (young patients), clinical presentation (aggressive tumor), and the presence of SCT are helpful to suggest the diagnosis. Other renal tumors at young age such as Wilms tumor and RCC usually have an expansile growth pattern (ball shaped) and are located in the renal cortex (Davidson et al. 1995).

In conclusion, an infiltrative, right-sided renal tumor with necrosis, caliectasis, and regional lymph adenopathy in a young patient with SCT is to be considered as a renal medullary carcinoma until proven otherwise (Blitman et al. 2005).

2.2 Leukemia, Plasmacytoma, Castleman Disease, and Lymphoma

2.2.1 Leukemia

Leukemic involvement of the kidney is rare and is seen more frequently in acute lymphoblastic forms (Pickhardt et al. 2000; Surabhi et al. 2008). The real frequency of renal involvement is difficult to assess, because of the limited contribution of imaging in staging (Pickhardt et al. 2000). Renal involvement can present as bilateral diffuse renal infiltration; more rarely, it presents as a focal expansile mass or a perirenal mass. Perirenal involvement is the result of extension of a renal mass in the perirenal space or more rarely as an isolated involvement (Pickhardt et al. 2000; Surabhi et al. 2008).

As imaging is nonspecific, clinical history may suggest the diagnosis, but percutaneous biopsy is required to achieve the diagnosis (Surabhi et al. 2008).

Granulocytic sarcomas (chloromas) are rare malignant tumors of granulocytic precursors that can present in up to 10 % of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and only rarely in acute lymphocytic leukemia. On imaging studies, they present as focal hypovascular soft-tissue masses in one or both kidneys (Surabhi et al. 2008).

2.2.2 Plasmacytoma

Two subgroups are distinguished: solitary lesions (plasmacytoma) and multiple lesions (multiple myeloma or Kahler’s disease). Extramedullary plasmacytoma is infrequent but can involve the kidney.

On imaging, plasmacytoma presents as a solitary infiltrative or expansile mass without specific radiological features.

In isolated renal plasmacytoma, diagnosis is usually based on the occurrence of Bence Jones proteinuria. In case of the absence of tumor-producing immunoglobulins, the diagnosis is only obtained by histopathologic analysis (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

2.2.3 Castleman Disease

Castleman disease is an infrequent idiopathic lymphoproliferative disorder which sporadically involves the retroperitoneum (Enomoto et al. 2007). Renal and perirenal involvement are rare. Unicentric and multicentric Castleman disease are distinguished. Multicentric Castleman disease is seen in association with Kaposi sarcoma and is frequently observed in patients with AIDS. Multicentric Castleman disease tends to be more aggressive and has a poor prognosis.

Imaging findings vary widely depending on the clinical presentation and histological subtype. Hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathies, and ascites tend to be present.

Unicentric Castleman disease displays as a well-defined, homogeneous, solitary intra-abdominal mass (Surabhi et al. 2008).

2.4 Rare Benign Mesenchymal Tumors of the Kidney

Mesenchymal tumors are tumors that are composed of mesenchymal tissue (vascular, adipose, fibrous, etc.).

The most common benign mesenchymal tumor is the renal angiomyolipoma (Katabathina et al. 2010). The more infrequent benign mesenchymal tumors are discussed.

2.4.1 Renal Leiomyoma

Renal leiomyomas are rare benign mesenchymal tumors, found in ± 5 % of autopsy (Katabathina et al. 2010; Surabhi et al. 2008). They mostly originate from the renal capsule (smooth muscle cells) but can also originate from the renal pelvis (muscularis) or cortex (vascular smooth muscle) (Katabathina et al. 2010; Surabhi et al. 2008). Renal leiomyomas are divided into two groups: the more frequent, incidentally found, and asymptomatic cortical leiomyomas smaller than 2 cm and the large renal leiomyomas that generally become symptomatic.

The large leiomyomas appear more often in white women older than 20 years of age. In thin patients, the tumor may be palpable and cause flank pain and rarely hematuria (Tessler et al. 1998).

At imaging leiomyoma presents as a well-circumscribed mass lesion. Unenhanced CT shows a slight hyperdense mass. The enhancement of the lesion on CT is homogeneous. Cystic or myxoid degeneration, calcification, and hemorrhage can be present in larger lesions (Katabathina et al. 2010; Surabhi et al. 2008; Tessler et al. 1998). MRI shows a T2 and T1 homogeneous hypointense mass and heterogeneous signal in the larger tumors (cystic degeneration, calcifications, or hemorrhage (Katabathina et al. 2010)).

Frequently, a distinct plane is distinguishable between the tumor and the kidney without parenchymal distortion, confirming the capsular origin of the tumor. Occasionally, the mass can be extremely exophytic or attached to the cortex by only a small stalk (Wagner et al. 1997). However, imaging findings are nonspecific: a peripheral, exophytic, well-demarcated, solid renal mass in a middle-aged woman should suggest the possibility of renal leiomyoma (Tessler et al. 1998).

The differential list includes leiomyosarcoma and RCC. Leiomyosarcomas tend to be larger and less encapsulated, but sometimes they mimic a leiomyoma. Biopsy may be an option for decision on further management (Roy et al. 1998).

2.4.2 Renal Lipoma

A primary renal lipoma is a very rare benign renal neoplasm. It is most often located in the cortex (Katabathina et al. 2010). As in leiomyoma, small and large lesions are distinguished. When large, they may become palpable and cause flank pain and, rarely, hematuria. Renal lipoma contains more nonadipose components than subcutaneous lipomas. These nonadipose components are mesenchymal elements or areas of fat necrosis and present as nodular or globular regions on imaging.

On imaging, a renal lipoma presents as a well-circumscribed fatty mass. On CT, this results in homogeneous negative density values (macroscopic fat). On MRI, the mass is T1 hyperintense on in-phase images and hypointense on out-of-phase images, T2-weighted images, and fat-saturated images. In smaller lesions, chemical shift characteristics allow the confirmation of subtle areas of fat more accurately compared to CT.

The differential diagnosis is angiomyolipoma. In lipoma, other soft-tissue components, with the exception of feeding vessels, are less prominent than in angiomyolipoma.

Larger lipomas are more heterogeneous due to areas of fat necrosis. Thus, the differential diagnosis expands to liposarcoma. Biopsy may then be required (aimed at nodular and globular areas) (Chiang et al. 2006).

2.4.4 Renal Lymphangioma

Renal lymphangioma is a rare benign renal neoplasm, occurring uni- or bilaterally. This lesion is probably a developmental anomaly of the perirenal lymphatic system, rather than a tumoral proliferation.

There is no sex predilection and the tumor mostly affects adults. Evolution of this lesion is variable, with in some cases the presence of spontaneous resolution (Katabathina et al. 2010).

On imaging, a lymphangioma presents as a uni- or multilocular cystic lesion, focal or diffuse. Contrast-enhanced imaging can sometimes show peripheral or septal enhancement. It is located most often in the perirenal space or renal sinus (Katabathina et al. 2010; Surabhi et al. 2008). The lesion is usually T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense at MR imaging. MRI signal intensity can vary if hemorrhage or debris is present in the lesion (Katabathina et al. 2010).

The perirenal space can be affected, and in the case of perirenal lymphangiomatosis, there are multiple cystic masses present bilaterally in the perirenal mesenchyme (Surabhi et al. 2008). Sometimes in association with a renal lymphangioma, linear fluid-filled structures are noted in the retroperitoneum, which are probably dilated lymphatic channels (Katabathina et al. 2010).

2.4.5 Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor (Reninoma)

Juxtaglomerular cell tumors are very rare benign renin-producing tumors with a female predominance. They occur in adolescence or early adulthood (Beaudoin et al. 2008).

They originate from the myoendocrine cell of the juxtaglomerular apparatus (Katabathina et al. 2010).

They are an extremely rare cause of secondary hypertension.

Symptoms are secondary to the renin production and include moderate to severe headache (hypertension), polydipsia, polyuria, enuresis, and sometimes neuromuscular pains (hypokalemia).

On clinical examination, patients show moderate to severe hypertension. Elevated peripheral renin level with signs of secondary hyperaldosteronism is seen on blood analysis (Dunnick et al. 1983).

Tumorectomy or partial nephrectomy is the gold standard therapy with normalization of blood pressure soon postoperatively.

Histologically, reninoma has benign characteristics, but recent case reports have shown that vascular invasion and metastases may occur. Malignant behavior is observed in older patients with a large reninoma that has been present for many years (Beaudoin et al. 2008).

A reninoma most often presents as a small (2–3 cm) solitary mass on imaging studies, located subcapsularly. Occasionally, they can occur near the renal pelvis or in the perinephric space. The latter presumably occurs from perirenal embryonic rests (Dunnick et al. 1983).

They present rarely as a large mass which usually suggests the long-standing presence of this tumor.

Hemorrhage and necrosis can be present.

On ultrasound, a reninoma is homogeneously hyperechogenic; sometimes hypoechogenic areas are present due to hemorrhage or necrosis. On unenhanced CT scan, a reninoma is hypo- to isodense to the renal parenchyma and hypovascular in the arterial phase, despite profuse vascularity. This can be explained by a vasoconstriction induced by renin (Katabathina et al. 2010; Pedrosa et al. 2008).

On MRI, a reninoma is T1 hypointense, T2 hypointense, and hypovascular after contrast administration (Pedrosa et al. 2008).

Imaging features are very nonspecific. Therefore, the notice of hypertension, hyperreninism in the absence of renal artery stenosis, and the presence of a renal mass should suggest a juxtaglomerular cell tumor.

Other differential diagnoses for hypertension and hyperreninism and secondary hyperaldosteronism are renal artery stenosis, incipient malignant hypertension, other renin-secreting tumors (renin-secreting Wilms tumor or RCC, very rare renin-secreting lung, pancreatic, ovarian, liver, or orbital tumor), and other masses that compress the renal artery or parenchyma (larger than reninoma) (Dunnick et al. 1983; Garel et al. 1993).

2.4.6 Renomedullary Interstitial Cell Tumor (Medullary Fibroma)

Renomedullary interstitial cell tumor originates from the interstitial cells of the medulla. The lesions smaller than 5 mm are asymptomatic. Rarely, the lesions are large and then they may cause flank pain and hematuria.

Resection is advised when the lesion becomes symptomatic.

CT usually shows a small, hypodense, nonenhancing lesion, located in the renal medulla. If larger, the lesion may become polypoid and can protrude in the renal pelvis.

The lesion is T1 and T2 hypointense on MR imaging, due to the presence of collagenous tissue (Katabathina et al. 2010).

2.4.7 Solitary Fibrous Tumor

A solitary fibrous tumor is a spindle cell tumor usually originating in the pleura. Extrapleural locations including the kidney are rarely reported. It is suggested to be a tumor of primitive mesenchymal cells with features of multidirectional differentiation (Hanau and Miettinen 1995; Katabathina et al. 2010).

Renal solitary fibrous tumor usually arises from the renal capsule, but occasionally appears in the cortex, pelvis, or peripelvic connective tissue (Gelb et al. 1996; Katabathina et al. 2010). It is considered a benign tumor, but in rare occasions, malignancy can be present (Gelb et al. 1996). Resection is the treatment of choice (Katabathina et al. 2010).

On imaging, they present as a well-defined, large, homogeneous, and relatively hypovascular mass (Fig. 4). A typical cortical claw sign is absent, witnessing its extraparenchymal origin. Intralesional necrosis, calcifications, and cysts are infrequently encountered (Pedrosa et al. 2008; Katabathina et al. 2010). On MRI, the lesion is predominantly T2 hypointense and homogeneous T1 isointense to the renal capsule (Johnson et al. 2005; Pedrosa et al. 2008). Contrast enhancement is limited in the arterial phase and heterogeneous in the delayed phase (Johnson et al. 2005; Pedrosa et al. 2008).

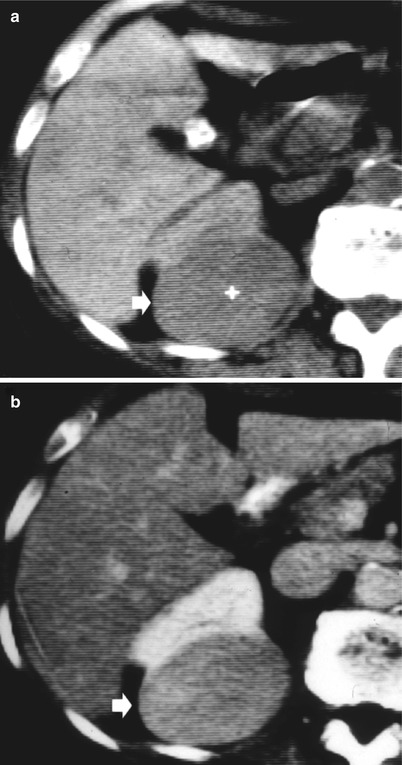

Fig. 4

Renal solitary fibrous tumor. (a) Well-defined, large, homogeneous, and relatively hypovascular mass (arrow) after iodinated-contrast agent injection (b) with a slightly heterogeneous appearance (Courtesy of Prof. Quaia)

2.4.8 Extra-adrenal Myelolipoma

Myelolipoma is a rare benign monoclonal tumor containing a mixture of normal hematopoietic cells and mature lipomatous tissue (Kumar and Duerinckx 2004). Normally, this tumor is located in the adrenal gland. Extra-adrenal myelolipomas are rare and occur mostly in perirenal or presacral area.

Age at presentation is the sixth decade in the extra-adrenal form, while adrenal myelolipoma is most often found (incidentally) in the fifth decade. Extra-adrenal myelolipomas show a female predominance.

On imaging, an extra-adrenal myelolipoma presents as a heterogeneous mass consisting of hypervascular soft-tissue and macroscopic fat. The aspect of the lesion depends on the dominating tissue component. At MR, high signal on T1- and T2-weighted images is present due to the fat component. Other areas show intermediate T1 and T2 signal due to marrow component (mimicking the signal of the spleen) (Heller et al. 2012).

The differential diagnosis with other fat-containing lesions is very difficult. Biopsy may be required (Surabhi et al. 2008).

2.5 Mesoblastic Nephroma

Mesoblastic nephroma (fetal renal hamartoma or leiomyomatous hamartoma) is the most common solid renal tumor in the first 3 months of life. Sometimes it can be detected on prenatal ultrasound (Lowe et al. 2000).

A slight male predominance is noted (Lowe et al. 2000).

It is commonly located near the renal hilum (Prasad et al. 2005). It is usually detected on clinical examination as a palpable abdominal mass. Rarely, hematuria is present.

On imaging, mesoblastic nephroma presents as a solitary, relatively homogeneous solid mass in the renal sinus.

On ultrasound, it presents homogeneously hypoechoic, on CT homogeneously hypodense, and on MRI T1 and T2 hypointense (Prasad et al. 2005). Hemorrhage and necrosis are uncommon.

Nephrectomy is the preferred therapy as mesoblastic nephroma has a relative benign behavior (Lowe et al. 2000).

2.7 Multilocular Cystic Tumor

Multilocular cystic tumor consists of a spectrum from multilocular cystic nephroma to a cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma (Lowe et al. 2000). They are rare, benign encapsulated lesions consisting of multiple noncommunicating cysts of varying size (Madewell et al. 1983). This tumor has a bimodal distribution, affecting boys between 3 months and 4 years of age and women over 40 years old (Madewell et al. 1983). They are usually detected incidentally (Lowe et al. 2000).

On imaging, multilocular cystic tumors present as a unilateral, solitary, well-circumscribed mass consisting of multiple cysts of varying size. Herniation of this mass into the renal pelvis and ureter is frequently observed. Calcification, hemorrhage, and necrosis are infrequent (Prasad et al. 2005).

When the cystic spaces are small, the tumor may mimic a solid lesion.

Because multilocular cystic nephroma is extremely rare in adult males, a predominately cystic or multicystic mass lesion should be considered as a cystic RCC.

Ultrasound is the key modality to confirm the cystic nature of this lesion (Lowe et al. 2000).

On CT, there is no secretion of contrast into the cysts (Lowe et al. 2000).

On MRI, the cyst fluid can be variable in signal intensity depending on its composition. The fibrous capsule is hypointense on every sequence.

The septations are usually regular and present a variable thickness. These septations enhance moderately on contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, CT, and MR.

Cystic nephroma and cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma cannot be differentiated on imaging studies.

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) can be differentiated from a multilocular cystic tumor by the absence of normally functioning renal parenchyma in MCDK. Sometimes in MCDK, there is a central core of solid dysplastic tissue that enhances, but this enhancement is different from the enhancement of normal renal parenchyma.

Segmental MCDK occurring in the obstructed part (generally the upper pole) in patients with complete ureteral duplication may be difficult to differentiate from multilocular cystic nephroma (Hopkins et al. 2004).

Nephrectomy is curative (Prasad et al. 2005). Tumorectomy should be complete, including the suburothelial component, to avoid local recurrency.

2.8 Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) of the Kidney

In the literature, there are just a few cases reported of renal NET: renal somatostatinoma, renal VIPoma, renal carcinoid, and renal pheochromocytoma (Hamilton et al. 1980; Isobe et al. 2000; Melegh et al. 2002; Walsh et al. 1996). In the case report of the VIPoma, it was not clear if the lesion was a primary lesion or metastatic (Hamilton et al. 1980).

Primary carcinoid tumor of the kidney (Fig. 5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree