Chapter Outline

The diagnostic pitfalls in cross-sectional imaging studies of the liver include variants of normal anatomy, developmental anomalies, and postsurgical changes. Others are often related to intravenous contrast material and scanning at various hepatic phases. This chapter focuses on anatomic variants and anomalies and describes how they can be recognized because they may simulate pathologic processes.

Whereas congenital abnormalities of human liver are rare, hepatic anatomic variants are relatively common and represent normal interindividual variation of liver morphology. Such variants include diaphragmatic slips, “sliver of liver” (a leftward extension of the lateral segment of the left lobe), and variants related to the papillary process of the caudate lobe.

There are many kinds of congenital hepatic abnormalities that result from disturbed development of the liver. There are many variations of the hepatic vascular anatomy that may affect liver morphology. The anomalies that result from excessive development of hepatic tissue occur as a lobar anomaly and include Riedel’s lobe as well as other accessory lobes. Those resulting from defective development of the liver include agenesis, hypoplasia, and aplasia of the right or left hepatic lobes. Agenesis refers to complete absence of a lobe, whereas hypoplasia represents a small hepatic lobe that is diminutive but otherwise normal. Aplasia is defined as a small lobe that is structurally abnormal and contains abundant connective tissue, scattered hepatic parenchyma, numerous bile ducts, and abnormal blood vessels.

The position and orientation of the liver may also be altered during embryologic development, resulting in situs inversus, situs ambiguus, and liver herniation. Bipartite liver is extremely rare and occurs when the right and left hepatic lobes are in their respective upper quadrants and are connected by a bridge of tissue.

Hepatic Embryology

During the third week of fetal life, the liver primordium appears as an outgrowth of endodermal epithelium at the distal end of the foregut. This outgrowth, known as the hepatic diverticulum or liver bud, consists of rapidly proliferating cell strands that penetrate the septum transversum, which is the mesodermal plate between the primitive heart and the stalk of the yolk sac. While the hepatic cell strands continue to penetrate into the septum transversum, the connection between the hepatic diverticulum and the distal foregut narrows, thus forming the bile duct.

With further development, the epithelial liver cords intermingle with the vitelline and umbilical veins, forming the hepatic sinusoids ( Fig. 85-1 ). The liver cords differentiate in the hepatocytes and form the lining of the biliary ducts. The Kupffer cells and connective tissue cells of the liver are derived from the mesoderm of the septum transversum.

Normal Anatomic Variants

Accessory Fissures and Diaphragmatic Slips

The two main fissures of the liver are the fissures for the falciform ligament and the ligamentum venosum. However, the liver may also contain accessory and pseudoaccessory fissures. True accessory fissures are rare and are the result of an inward folding of the peritoneum, usually involving the undersurface of the liver. The most common one is the inferior accessory fissure, which divides the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe into lateral and medial portions.

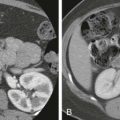

Pseudoaccessory fissures are common anatomic variants that result from invaginations of diaphragmatic muscle fibers, usually along the superior surface of the liver ( Fig. 85-2 ). They are more frequently seen involving the right hepatic lobe, but they can occur on the left as well. These infoldings of the diaphragm often seen in elderly patients can give the liver a scalloped or a lobular appearance and should not be mistaken for macronodular liver in cirrhosis. They can also be a cause of hypodense peripheral pseudomasses on CT ( Fig. 85-3 ). On ultrasound, they may occasionally appear as an echogenic focus in one plane; however, on scanning in the orthogonal plane, the true linear morphology of a fissure is revealed.

Sliver of Liver

Leftward extension of the lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe is referred to as sliver of the liver. It is a common anatomic variant and appears as a crescentic density that wraps around the spleen ( Fig. 85-4 ) and may lie lateral, medial, and even posterior to the spleen. It is important not to confuse this variant with either perisplenic or perigastric disease. On ultrasound, this variant can mimic perisplenic hypoechoic collections, and the correct diagnosis is achieved by using color Doppler imaging and documenting continuity with the remainder of the left hepatic lobe.

Papillary Process of the Caudate Lobe

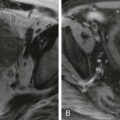

The caudate lobe is a portion of the liver that extends medially from the right lobe between the inferior vena cava and the fissure for the ligamentum venosum. On occasion, it is divided into two processes. The anterior medial extension of the caudate lobe is known as the papillary process, which extends anteriorly and to the left in the region of the lesser sac. The posterior extension is referred to as the caudate process. Below the porta hepatis, this papillary process can appear separate from the caudate process by a cleft in its inferior margin and can mimic a periportal node or a mass near the head of the pancreas or near the inferior vena cava ( Fig. 85-5 ). However, on multidetector computed tomography (CT) and by use of multiplanar reformation, this anatomic variant is easily recognizable.

Anatomic Anomalies

Riedel’s Lobe

Described by Bernhard Moritz Carl Ludwig Riedel, a German surgeon (1846-1916), Riedel’s lobe is the most common accessory lobe of the liver, and it is seen most frequently in asthenic women. It is a tonguelike projection from the anterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver that can extend quite inferiorly in some patients. It usually extends along the right paracolic gutter into the iliac fossa ( Fig. 85-6 ) and can be 20 cm or more in length. On physical examination, this anomaly can be mistaken for an enlarged liver or a right renal mass. Riedel’s lobe may be connected to the liver by a pedicle consisting of hepatic parenchyma or fibrous tissue. It is usually asymptomatic and is discovered incidentally; however, it may be complicated by torsion with gangrenous changes. On occasion, the left lobe can behave like a Riedel lobe and extend inferiorly in the abdomen.