Anti– N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis is a severe but potentially reversible neurologic disorder that is clinically recognizable in children and adolescents. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to facilitate recovery. Treatment consists of corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasma exchange as first-line therapy followed by cyclophosphamide or rituximab, if necessary, as second-line immunotherapy. Patients with tumor-associated encephalitis benefit from tumor resection. More than 75% of patients make a substantial recovery, which occurs in the reverse order of symptom presentation associated with a decline in antibody titers.

Key points

- •

Anti– N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis is a severe but potentially reversible neurologic disorder that is clinically recognizable in children and adolescents.

- •

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to facilitate recovery.

- •

The clinical syndrome is confirmed by the presence of NMDA receptor antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid or serum.

- •

Treatment consists of corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasma exchange as first-line therapy followed by cyclophosphamide or rituximab, if necessary, as second-line immunotherapy. Patients with tumor-associated encephalitis benefit from tumor resection.

- •

More than 75% of patients make a substantial recovery, which occurs in the reverse order of symptom presentation associated with a decline in antibody titers.

Introduction

In 2005, 4 young women with a syndrome of acute psychiatric symptoms, seizures, memory loss, encephalopathy, and hypoventilation associated with an ovarian teratoma were reported. These women were found to have antibodies that reacted with neuronal cell-surface antigens. These antibodies were subsequently found out to be autoantibodies targeting the NR1 and NR2 N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors in another series of 12 women with a similar neuropsychiatric syndrome in the presence of ovarian teratoma. These reports were just the beginning of what has now turned out to be an increasingly reported new immune-mediated neurologic syndrome, anti-NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-mediated encephalitis. A seminal publication in 2008 by Dalmau and colleagues described the syndrome in great detail and outlined its salient characteristics in a large cohort of 100 patients. The majority of reported subjects in the cohort were adult females who had an ovarian teratoma in the background. Since this article was published, however, it has become increasingly clear that the syndrome is not restricted to adult females but can also be seen in adult males and children of either sex in the absence of an associated systemic neoplasm. It appears that this syndrome is still underrecognized as its existence is only being gradually appreciated. However, other previously reported disorders could perhaps have been anti-NMDAR encephalitis; these include idiopathic encephalitis with psychiatric manifestations or dyskinesias, coma associated with intense bursts of abnormal movements and long-lasting cognitive and behavioral disturbances, acquired reversible autistic syndrome in acute encephalopathic illness in children, immune-mediated chorea encephalopathy syndrome in childhood, juvenile acute nonherpetic encephalitis, and encephalitis lethargica. Moreover, with increasing literature the syndrome appears to encompass a far wider spectrum of clinical presentation than initially described. The discovery of anti-NMDAR encephalitis has led to the detection of a growing list of many other autoimmune synaptic receptor encephalitides, including those mediated by antibodies toward the 2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid (AMPA) receptor, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B receptor, and leucine-rich, glioma-B inactivated 1 (LGI1) receptor. The LGI1 receptor is the antigen previously ascribed to voltage-gated potassium channel encephalitis. These immune-mediated responses are now providing an understanding of the function of the neurotransmitter receptors affected by these antibodies. This article focuses on anti-NMDAR encephalitis in the pediatric age group.

Introduction

In 2005, 4 young women with a syndrome of acute psychiatric symptoms, seizures, memory loss, encephalopathy, and hypoventilation associated with an ovarian teratoma were reported. These women were found to have antibodies that reacted with neuronal cell-surface antigens. These antibodies were subsequently found out to be autoantibodies targeting the NR1 and NR2 N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors in another series of 12 women with a similar neuropsychiatric syndrome in the presence of ovarian teratoma. These reports were just the beginning of what has now turned out to be an increasingly reported new immune-mediated neurologic syndrome, anti-NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-mediated encephalitis. A seminal publication in 2008 by Dalmau and colleagues described the syndrome in great detail and outlined its salient characteristics in a large cohort of 100 patients. The majority of reported subjects in the cohort were adult females who had an ovarian teratoma in the background. Since this article was published, however, it has become increasingly clear that the syndrome is not restricted to adult females but can also be seen in adult males and children of either sex in the absence of an associated systemic neoplasm. It appears that this syndrome is still underrecognized as its existence is only being gradually appreciated. However, other previously reported disorders could perhaps have been anti-NMDAR encephalitis; these include idiopathic encephalitis with psychiatric manifestations or dyskinesias, coma associated with intense bursts of abnormal movements and long-lasting cognitive and behavioral disturbances, acquired reversible autistic syndrome in acute encephalopathic illness in children, immune-mediated chorea encephalopathy syndrome in childhood, juvenile acute nonherpetic encephalitis, and encephalitis lethargica. Moreover, with increasing literature the syndrome appears to encompass a far wider spectrum of clinical presentation than initially described. The discovery of anti-NMDAR encephalitis has led to the detection of a growing list of many other autoimmune synaptic receptor encephalitides, including those mediated by antibodies toward the 2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid (AMPA) receptor, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B receptor, and leucine-rich, glioma-B inactivated 1 (LGI1) receptor. The LGI1 receptor is the antigen previously ascribed to voltage-gated potassium channel encephalitis. These immune-mediated responses are now providing an understanding of the function of the neurotransmitter receptors affected by these antibodies. This article focuses on anti-NMDAR encephalitis in the pediatric age group.

Epidemiology

The incidence of anti-NMDAR encephalitis in both children and adults is unknown at present. It appears to be more common than previously thought, given the increasing literature. A retrospective study of adults with encephalitis of unknown origin identified NMDAR antibodies in 1% of patients admitted to intensive care. A multicenter, population-based prospective study of causes of encephalitis in adults and children in the United Kingdom showed that 4% of patients had anti-NMDAR encephalitis. The most common immune-mediated causes were acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, followed by anti-NMDAR encephalitis and other antibody-associated encephalitides. The California Encephalitis project tested 20 patients and identified 10 as anti-NMDAR positive. All 10 patients had negative viral studies, but 4 were positive for serum Mycoplasma immunoglobulin M antibodies. The median age was 18.5 years, with a predilection for Asians and Pacific Islanders. In a case series in children and adults in 2009, 40% were children younger than 18 years with the youngest child being only 23 months old. In the Dalmau series of 100 patients, 22 were children younger than 18 years, 55% of whom had an underlying tumor. A child as young as 20 months has been reported with symptoms and neuronal antibodies consistent with anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Clinical presentation

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis presents as a characteristic syndrome that develops in progressive stages of illness and recovery. The clinical syndrome was first defined in a series of 100 patients, which included adults and children. This study was followed by a second series that concentrated on 32 children younger than 18 years who were compared with 49 adults identified at the same time. Individual case reports and smaller case series have substantiated these findings. The phenotype in adults and children is similar, except that autonomic dysfunction and hypoventilation are probably less common and less severe in children.

Prodromal Features

At the onset of the syndrome, symptoms including fever, headache, rhinitis, vomiting, and diarrhea have been recorded in 48% of children.

Psychiatric Features

Within 2 weeks, patients usually develop psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, paranoia, fear, psychosis, mania, and insomnia. Social withdrawal and stereotypical behavior are also possible. In a series of mostly adult patients, 85% presented initially to a psychiatrist for anxiety, agitation, and visual or auditory hallucinations. Of 32 children, 87% presented with changes in behavior or personality. The recognition of psychosis in young children is challenging. The behavioral changes include increased tantrums, irritability, and hyperactivity. Behavior can be hypersexual or aggressive. Acute mania with psychosis and a catatonic state has been reported in an adolescent female with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. As patients with psychosis are often treated initially with neuroleptic medications, neuroleptic malignant syndrome can compound the clinical picture because symptoms of rigidity, autonomic instability, and elevation of muscle enzymes, typically associated with this syndrome, can occur independently in anti-NMDAR encephalitis in the absence of neuroleptics.

Neurologic Features

In children, the chief features include movement disorders, seizures and cognitive problems. Other features reported in adults appear to be less common in children such as autonomic instability and sleep disorders.

Movement disorders

Movement disorders are a very frequent neurologic feature of this syndrome and have been reported in 84% of a case series in children with orofacial dyskinesias occurring in 45%, choreoathetosis in 32%, and dystonia in 32%. Oculogyric crisis, rigidity, and opisthotonic postures are also reported. Orofacial dyskinesias are described as chewing, tongue thrusting, lip smacking, and facial grimacing movements. There are descriptions of more complex, stereotyped movements including pelvic thrusting, pseudo–piano-playing motions, and writhing of the extremities. Some movements, such as pelvic thrusting, have the potential to be considered as nonorganic phenomena. Limb movements mimicking epileptic seizures may also occur. Patients may develop episodic opisthotonus, dystonia, and oculogyric crises, associated with tachycardia and hypertension, which is suggestive of autonomic storming. Opsoclonus-myoclonus has been reported in a woman with anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Seizures

Seizures are reported in about 77% of children, and can be difficult to recognize and treat. Both partial and generalized seizures as well as status epilepticus can occur, although partial seizures seem to predominate. Abnormal repetitive movements may mimic partial seizures, necessitating video electroencephalogram (VEEG) monitoring for definitive diagnosis of seizures in some cases. The presentation of partial status epilepticus in anti-NMDAR encephalitis may lead to the consideration of a diagnosis of Rasmussen syndrome. Unexplained new-onset epilepsy in young women and adolescents may be a feature of anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Cognitive problems

Short-term memory loss is underestimated, as the assessment of memory is affected by the psychiatric symptoms and speech problems. Retrospectively, patients often report amnesia of the illness. A rapid deterioration of language, ranging from reduced verbal output and echolalia with echopraxia to frank mutism, is common. This symptom may be followed by a decreased level of consciousness and alternate periods of agitation and catatonia. Dissociative responses to stimuli are often noted.

Autonomic Dysfunction

Tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperthermia occurred in 86% of a case series of 32 children. Autonomic instability and hypoventilation are reported to be less severe, and dysrhythmias in children are less likely to require pacing than in adults. Mechanical ventilation may sometimes be needed for central hypoventilation and airway protection. Hyperthermia is common throughout the disease, frequently leading to extensive investigations to exclude infectious processes. Hypersalivation and urinary incontinence are some of the other frequently reported symptoms.

Miscellaneous Features

Insomnia is reported as an early presenting sign, at least in adults. Sleep-wake cycles are disrupted and patients arouse frequently. During recovery patients may have hypersomnia. Symptoms of hypothalamic dysfunction have been recognized in a few patients. Recurrent optic neuritis with transient cerebral lesions has been reported in one patient.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis has also been reported in an adolescent female, with recurrent relapses associated with extensive longitudinal myelitis and optic neuritis mimicking neuromyelitis optica.

Physical Examination

Systemic and neurologic signs are nonspecific. There are no markers in the clinical examination that can suggest anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Hence, a low threshold of suspicion is warranted in patients with a constellation of movement disorder, seizures, and neuropsychiatric problems. Patients show signs of a diffuse encephalopathy, indicating that there is neurologic dysfunction of subcortical, limbic, and frontostriatal circuitry. Various levels of altered consciousness are possible. Signs of increased intracranial pressure are usually uncommon, although they may be secondarily present in the wake of prolonged status epilepticus. Neurologic examination may reveal nonspecific signs of diffuse cerebral dysfunction such as exaggerated deep tendon reflexes, extensor plantar responses, and tone abnormalities, in addition to movement disorders. Soft neurologic signs such mild ataxia and difficulties with fine motor coordination can also be seen.

Investigations

Neuroimaging

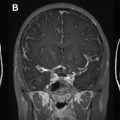

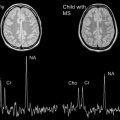

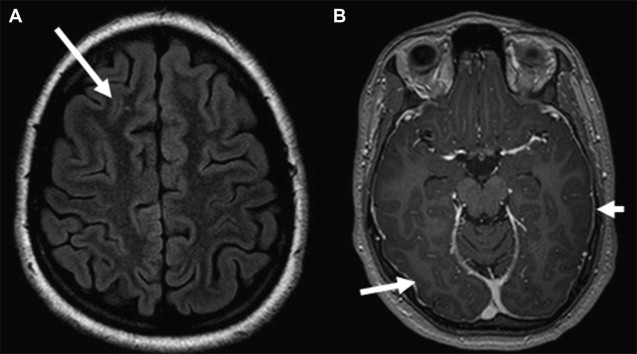

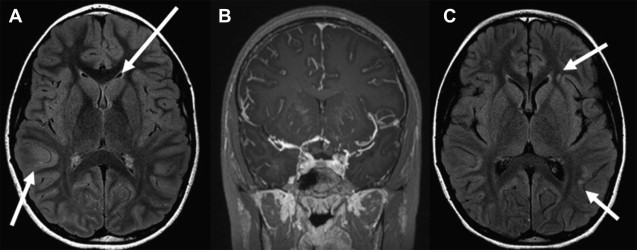

Computed tomography (CT) of the head is not useful because of its poor sensitivity. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain is unremarkable in 50% of cases. In the other 50%, MR imaging may show nonspecific T2 or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal hyperintensity within the hippocampus; cerebellar, frontobasal, or insular cortex; basal ganglia; brainstem; and, occasionally, the spinal cord. These changes are usually mild or transient, and have been associated with contrast enhancement in the hyperintense areas or the meninges. Occasionally the MR imaging shows extensive T2 FLAIR abnormalities. The radiologic differential diagnosis with these abnormalities remains broad. Follow-up brain MR imaging either remains normal or shows minimal change. Patients with refractory seizures have been reported to show brain atrophy. Lesions can be transient and nonenhancing, and may have a demyelinating appearance. MR spectroscopy has not yet been documented to be of any proven value. In short, no clear patterns of brain involvement are evident in this condition ( Figs. 1–3 ), which makes a diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis based solely on neuroimaging features rather difficult.

Functional Neuroimaging

Most of the literature on functional neuroimaging in anti-NMDAR encephalitis is case based and anecdotal. The utility of functional neuroimaging modalities has not been systematically studied. 18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging showed cortical hypometabolism in 2 young girls aged 3 years and 7 years, with relapsing anti-NMDAR encephalitis; this included the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortex, and the thalamic nuclei. PET was reportedly more sensitive than MR imaging in these patients. However, a previous report of acute anti-NMDAR encephalitis contrasted this with signs of cortical hypermetabolism. An adolescent with anti-NMDAR encephalitis was found to have abnormal cerebral blood flow in on 99m Tc-labeled d,l -hexamethylpropylene amine oxime single-photon emission CT (HMPAO SPECT). Images showed multiple focal areas of radiotracer uptake in a corticobasal hyperperfusion pattern, which suggested the possibility of frontobasal circuitry involvement. Repeated brain 99m Tc-HMPAO SPECT showed almost complete normalization.

Electroencephalography

Electroencephalograms (EEGs) are consistently abnormal in most patients, and show nonspecific slowing and disorganization of background activity. These findings may be associated with electrographic seizures, which are more common in the initial disease stage. During the catatonic stage slow, continuous, delta, or theta, rhythmic activity predominates. The slow rhythmic activity has not been associated with movement abnormalities and has not responded to antiepileptic medication. VEEG monitoring may be beneficial in diagnosing seizures appropriately.

Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum

NMDARs form part of the ligand-gated cation channels, which play an important role in synaptic transmission and plasticity. The NMDARs are heteromers of NR1 subunits that bind to glycine and NR2 (A, B, C, or D) subunits, which bind to glutamate. The presence of NMDAR antibodies was confirmed by serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reactivity with hippocampal rat brain, cell-surface labeling hippocampal neurons in culture, and reactive NR1- or NR2-transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. Definitive diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis is established by demonstrating antibodies to the NR1 subunit in patients’ serum or CSF. In a series of children with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, all patients had CSF or serum antibodies that reacted with extracellular epitopes of the NR1 subunit. Paired CSF and serum samples from 21 patients showed stronger antibody reactivity in CSF. Patients with a teratoma had higher antibody CSF titers than those without a teratoma. Seven patients treated with empiric plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins had positive antibodies in CSF, but not in serum. Antibody titers may change over time. A patient who recovered showed a high serum antibody titer and absent or barely detectable CSF antibody titer at follow-up. Although viral encephalitis, stroke, epilepsy, and systemic lupus erythematosus have been associated with NMDAR antibodies, the NR1 receptor region appears to associate uniquely with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. This finding is consistent with an immune response, systemically triggered by a tumor or another unknown cause, which is reactivated and expanded in the central nervous system (CNS).

CSF white blood cells are often increased, in the range of fewer than 200/mm 3 , and pleocytosis was found in 87% of a series of children. Protein concentration is normal or mildly increased, and CSF-specific oligoclonal bands are positive in 60%. The immunoglobulin G (IgG) index and oligoclonal band testing are clinically useful, as they can be abnormal in the setting of normal CSF cell counts and protein concentrations.

Tumor Association

Approximately 80% of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis have so far been women. The detection of a tumor is dependent on age, gender, and ethnicity. Approximately 60% of patients have tumors proven to contain nervous tissue. In women, frequency of ovarian teratoma amounts to about 62%, whereas only 22% of men have associated tumors (testicular teratoma and small-cell lung cancer). In adolescent females younger than 18 and children younger than 14 years, tumors were diagnosed in 31% and 9%, respectively. The ovarian teratomas of 25 patients studied expressed NMDARs in each case. There is one case report of a child with anti-NMDAR encephalitis and neuroblastoma. Ovarian tumors were found in a few patients who had surgery with exploratory laparoscopies and blind oophorectomies, but in others no tumor was detected.

Pelvic or testicular ultrasonography is an appropriate initial screen for ovarian or testicular teratomas. MR imaging has been used as a more sensitive test for small ovarian tumors. Yearly screening for a tumor, particularly if the patient has a recurrence or continues to be symptomatic, is recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree