Pelvic pain is a frequent problem for women and may account for 10% to 40% of all gynecologic visits. It is the most common reason for laparoscopy in the United Kingdom, and in the United States, it is the second most common reason for laparoscopy and the most common reason for hysterectomies, accounting for 12% to 19% of all hysterectomies performed.

Diagnostic considerations encompass gynecologic and obstetric causes as well as nongynecologic etiologies. Because the selection of imaging modality is determined by the clinically suspected differential diagnosis, a careful evaluation of the patient should be performed and diagnostic considerations narrowed before a modality is chosen.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and transabdominal ultrasound (TAUS) of the pelvis have the ability to narrow the differential diagnosis and are the imaging modalities of choice when a gynecologic etiology is suspected. Sonography should also be considered when gastrointestinal or urinary tract pathology is suspected in the pregnant patient. Not only is it noninvasive, radiation free, and cost effective, but sonography also accurately delineates the architecture of the uterus and ovaries. Because of better anatomic resolution, TVUS should be used whenever possible, although a routine study usually includes both techniques, and TAUS provides more information when uterine and adnexal structures are beyond the field of view of the transvaginal probe. In addition, spectral and color or power Doppler imaging can be used to characterize vascularity to the ovaries, adnexal structures, and uterus, which may also be beneficial in narrowing the field of differential considerations. The majority of patients presenting with pelvic pain who have a normal pelvic ultrasound (US) are likely to have resolution of their pain, and further imaging is unlikely to yield positive results. There are a few situations in which TVUS may be contraindicated. These include premenarchal patients, the majority of virginal patients, and any patient who does not willingly consent to a vaginal examination. The examination may need to be discontinued in the patient with a narrow introitus who experiences discomfort at the time of transducer insertion. In general, TVUS can be performed in any patient in whom a bimanual examination is appropriate.

Computed tomography (CT) is used more frequently when a gastrointestinal or genitourinary abnormality is likely, although gynecologic disease is being detected with increasing frequency by CT as a result of 24-hour accessibility in many hospitals and advances in CT technology leading to faster acquisition times and multiplanar reformats.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually favored over CT for assessing the pregnant patient because of the lack of ionizing radiation but may be hampered by its lack of widespread availability, especially in the acute setting. MRI is also emerging as a problem-solving tool for specific indications, if further characterization of a disorder is required and when US is found to be inadequate. For example, if the patient’s pain fails to resolve or is more chronic in nature, MRI is often beneficial in the evaluation of adenomyosis and endometriosis, which usually demonstrate characteristic MRI findings.

Discussions of pelvic pain generally distinguish acute pelvic pain from chronic pelvic pain. Acute pain is intense pain characterized by sudden onset. Chronic pain is typically defined as noncyclic pelvic pain that lasts 6 months or longer and that is severe enough to cause functional disability or the need for medical care. Although chronic pelvic pain may occur in as many as 15% of the population, 60% go undiagnosed, in contrast to patients with acute pain, in whom a diagnosis is more likely to be reached. The time frame for the definition of chronic pain is arbitrary, and alternative durations such as 3 months have been suggested. In addition to acute and chronic pain, some pain is cyclic, referring to pain that is associated with the menstrual cycle. Dysmenorrhea (i.e., painful menstruation) is the most common form of cyclic pain.

This chapter provides an overview and an approach to the evaluation of the female patient with acute pelvic pain, chronic pelvic pain, and dysmenorrhea. Imaging findings of the causes of pain discussed briefly here are discussed in more detail in other chapters, including specific chapters on acute and chronic pelvic pain ( Chapter 10, Chapter 11 ).

Acute Pelvic Pain

Patients with acute pain may exhibit other nonspecific signs and symptoms, the most common being nausea, vomiting, and leukocytosis. History and physical examination can often suggest one or several likely diagnoses. Laboratory evaluations such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinalysis, and urine or serum pregnancy test in women of reproductive age are often helpful, but in many women, imaging will be needed to help make a diagnosis. A serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is usually performed when a menstruating woman presents with acute pelvic pain. Knowledge of pregnancy status is of utmost importance to determine whether ectopic pregnancy should be under consideration and to indicate any added concern for fetal exposure to ionizing radiation, making US the initial imaging modality of choice. A negative β-hCG essentially excludes the diagnosis of an intrauterine pregnancy and ectopic pregnancy because it becomes positive approximately 9 days after conception.

Pelvic US is the preferred imaging modality for the vast majority of women with acute pelvic pain. It may be tempting to perform CT because of its wide availability and rapid scan time, but pelvic US is generally the most appropriate imaging modality and spares the patient ionizing radiation. CT may be a reasonable first imaging method if the pain is thought likely to be of gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract origin.

Obstetrical Causes of Acute Pelvic Pain in the First Trimester

Ectopic pregnancy and failed intrauterine pregnancy are the most common obstetric causes of pain in the first trimester of pregnancy. Patients with either diagnosis may also have vaginal bleeding. TVUS is a highly sensitive tool to diagnose an intrauterine pregnancy after 5 weeks of gestation. Absence of cardiac activity in embryos greater than 5 mm is diagnostic of a failed pregnancy. Other sonographic features of a failed intrauterine pregnancy are discussed in Chapter 21 .

Studies published in the late 1980s that correlated the presence of a gestational sac using TVUS with β-hCG levels have played a crucial role in our ability to make the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. These studies documented the presence of a gestational sac by the time the hCG level was 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL (International Reference Preparation). When the β-hCG level is above this discriminatory zone, one should expect to see a gestational sac, and if not, an ectopic pregnancy becomes a stronger consideration. Because of human variability, user dependency, and technical limitations, however, this level should not be taken unconditionally.

The high specificity of adnexal sonographic findings for tubal pregnancy, which include the classic “tubal ring,” has been widely reported in the literature in patients with a positive pregnancy test and no intrauterine pregnancy. The most specific finding is the extrauterine sac with a live embryo, but because of its lack of sensitivity, the adnexal ring and the extraovarian adnexal mass are often used as the criteria to make the diagnosis and have been found to have a specificity of up to 100% depending on the risk of the population selected ( Figure 8-1 ). Doppler evaluation is generally not helpful because flow is often seen surrounding the corpus luteum and the tubal ring so that the tubal ring must still be identified separate from the ovary.

Gynecologic Causes of Acute Pelvic Pain

The most common gynecologic causes of acute pelvic pain in women include hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and adnexal torsion, but one should also be aware of other causes, especially in the postpartum patient. One may also need to consider mittelschmerz, which is the midmenstrual cycle pain associated with ovarian follicle rupture during ovulation. Pain from mittelschmerz is usually mild to moderate, self-limited, and imaging is not typically needed.

Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cysts

Pain symptoms are variable in patients with hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, and usually there are no distinguishing clinical features. If an ovarian cyst ruptures, the pain is often similar to that with ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The pain from ovarian cysts may be caused by internal hemorrhage, rupture or leakage, or large size. Sonographically, acute hemorrhage is isoechoic to hyperechoic and may be suggestive of a solid mass. With hemolysis and retraction of clot, a reticular network of strandlike echoes ( Figure 8-2 ), fluid–fluid levels, or congealed clot, which may appear as seemingly solid areas with concave margins, may be demonstrated on US. Color and spectral Doppler evaluation is characteristic with typical findings of peripheral color Doppler signal with low impedance arterial flow. In cases of cyst rupture, intraperitoneal fluid with internal echoes resulting from hemoperitoneum may be seen with US or the hemoperitoneum may be evident by CT ( Figure 8-3 ). MRI is not generally needed to make this diagnosis, although if performed, hemorrhagic cysts will show signal variation based on the age of blood products but are usually high signal on T1-weighted precontrast images.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

PID should be considered in patients who also have fever, leukocytosis, and cervical motion tenderness. Patients with acute salpingitis typically have bilateral adnexal pain. Right upper quadrant pain caused by inflammation around the liver may occasionally occur in patients with PID (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome). PID is usually an ascending infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhea , Chlamydia trachomatis , or superinfecting organisms from the vagina. Sonographic findings of the fallopian tubes are the most specific and conspicuous indicators of PID ( Figure 8-4 ). With progression of disease, there is exudation of pus from the distal fallopian tube, and the ovary can become involved. If a separate ovary is still visualized, this indicates a tuboovarian complex. A tuboovarian abscess results in complete breakdown of tubal and ovarian architecture so that separate structures are no longer identified.

If CT or MRI is performed, a pelvic abscess usually appears as a peripherally enhancing fluid collection ( Figure 8-5 ) and may contain gas. CT can demonstrate haziness and stranding within pelvic fat with obscuration of fascial planes and thickening of local ligamentous structures. MRI may reveal high signal on T2-weighted imaging corresponding to areas of inflammation within the parametrial soft tissues or the mesenteries of adjacent bowel loops in the pelvis.

Ovarian Torsion

The type of pain is variable in patients with ovarian torsion, but torsion should be more strongly considered in a patient with abrupt onset of severe unilateral pain, typically with nausea and vomiting. The pain caused by torsion may be severe and constant or can be intermittent when there is partial torsion or if the ovary undergoes torsion and detorsion. An enlarged, abnormal-appearing ovary appears to be a common denominator in most, if not all, cases of ovarian torsion. An irregular internal texture of the ovary seems to correlate with intraovarian hemorrhage ( Figure 8-6 ). Peripherally located follicles and homogeneous echoes centrally consistent with areas of edema within enlarged ovaries have also been reported, although these descriptors are nonspecific. Free fluid within the cul-de-sac is another nonspecific finding frequently associated with cases of ovarian torsion. On the other hand, a small amount of fluid is often physiologic in females of reproductive age. Doppler findings vary depending on degree of torsion and its chronicity. Absent arterial and venous flow by spectral Doppler US is most suggestive, but absent venous flow with preserved arterial flow is a common finding The presence of flow by Doppler US also cannot be comfortably used to exclude torsion because the presence of both arterial and venous flow has been demonstrated in more than 30% of surgically and pathologically proven torsed ovaries.

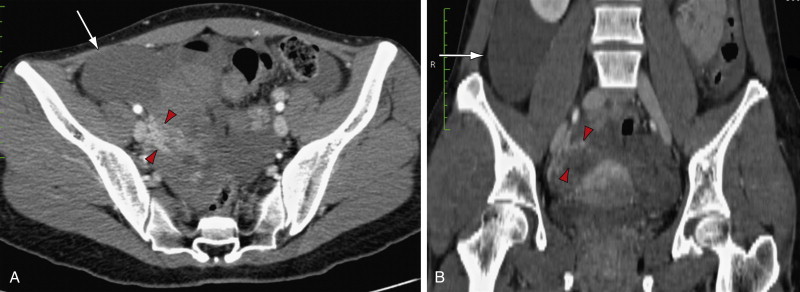

If CT is performed, findings include an ovarian mass ( Figure 8-7 ), thickened and edematous ovarian cortex, ipsilateral fallopian tube thickening, engorgement of ovarian vessels that may form a beaked configuration, ascites, abnormal position of the ovary, and ipsilateral deviation of the uterus. MRI findings of torsion are ovarian engorgement with marked increased signal on T2-weighted images, hemorrhage within the ovarian stroma, pelvic fluid, tubal thickening, ipsilateral deviation of the uterus, and twisted pedicle. In severe cases the enlarged ovary may show no enhancement.

Uterine Fibroids

Uterine fibroids may cause acute pelvic pain as a result of degeneration, torsion of a pedunculated subserosal fibroid, or uterine contractions in an effort to expel a pedunculated submucosal fibroid. Degeneration of fibroids does not necessarily cause pain, however, and many patients with degenerated fibroids are asymptomatic. US is useful to confirm the presence of fibroids, but other than for cystic degeneration, US usually does not show reliable features of degeneration. Hemorrhagic degeneration is the type of fibroid degeneration most often associated with pain, usually occurs during pregnancy, and is most readily diagnosed by MRI. There is high signal within the fibroid on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and no enhancement after administration of gadolinium chelate.

Considerations in the Postpartum Patient

In postpartum patients, entities such as endometritis and ovarian vein thrombosis should also be considered. Endometritis has variable and nonspecific imaging features on any modality and is generally a clinical diagnosis, based in part on a tender uterus and fever.

Although US is generally the initial imaging modality for postpartum complications, CT and MRI perform better for the diagnosis of ovarian vein thrombosis. Ovarian venous thrombosis appears as a tubular structure with enhancement of the periphery of the vessel surrounding a nonenhancing thrombus. The ovarian vein may be engorged, and there may be stranding surrounding the vessel, particularly in the setting of septic thrombosis. The right ovarian vein is involved in 80% to 90% of cases and can be confused with the appendix or ureter.

Nongynecologic Causes of Acute Pelvic Pain

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is the most common gastrointestinal cause of acute pelvic pain in women. The pain of appendicitis may start as diffuse and/or periumbilical pain that later migrates to the right lower quadrant. On physical examination, localized tenderness in the right lower quadrant, severe generalized muscle guarding, rebound tenderness, positive psoas sign (pain with forced hip flexion or passive hip extension), and obturator sign (pain with passive internal rotation of flexed thigh) suggest that appendicitis is likely. In adult women with these findings, contrast-enhanced CT is usually performed to exclude gynecologic and other gastrointestinal sources for pain before laparoscopy or laparotomy. In pregnant patients in whom appendicitis is a consideration, graded compression US in the right lower quadrant is often the initial imaging test but is usually inconclusive because of the enlarged uterus. MRI is the next most appropriate imaging test after US for suspected appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Appendicitis is the most common cause for emergency laparotomy during pregnancy.

Appendicitis can sometimes be recognized with either TAUS or TVUS by the presence of a thick-walled, tubular, noncompressible, aperistaltic structure measuring more than 3 mm in single-wall thickness arising from the cecum ( Figure 8-8 ). Sonographic detection of an appendicolith within the appendix, regardless of wall diameter, is highly specific in a symptomatic patient. Other findings include surrounding echogenic fat and increased color Doppler vascularity within the luminal wall consistent with inflammation. Although usually best depicted by the transabdominal approach using the graded compression technique first described by Puylaert in 1986, the proximity of bowel within the cul-de-sac to the TVUS probe may allow diagnosis by this method. Unfortunately the technique of graded compression required for this diagnosis is often not feasible in pregnant women beyond the first trimester because of the enlarged uterus.