The fallopian tubes play an important role in the fertilization process. The fallopian tubes provide a conduit for the ovum to travel from the ovary to the uterus. The ampullary portion of the fallopian tube is where fertilization of the ovum occurs. Damage to the fallopian tube can occur with infection, endometriosis, and fibrotic reaction, and can lead to tubal occlusion and peritubal adhesions. This can interfere with the normal transport of sperm, ovum, and fertilized ovum to the uterine cavity, leading to infertility. Tubal abnormalities and ovulatory failure are two of the most common causes of infertility, each of which occurs in 30% to 40% of cases. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is one of the most common causes of tubal and peritubal damage. The main source of disease is typically an ascending genital tract infection. Multiple imaging modalities can be used for the initial workup of the fallopian tubes.

Disease

Definition

PID refers to a large group of infectious conditions of the upper reproductive tract, including endometritis, salpingitis, and tuboovarian abscess (TOA). Salpingitis is an inflammation in the fallopian tubes usually caused by infection. There are two types of salpingitis: acute and chronic. Acute salpingitis causes the fallopian tube to become inflamed. The inner walls can adhere to each other, causing occlusion of the tube. The fallopian tube can also adhere to the adjacent peritoneal contents as a result of peritubal adhesions if not treated promptly with antibiotics. Chronic salpingitis is a milder form of infection with less severe symptoms that often follows an episode of acute salpingitis. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa (SIN) is a sequela of chronic infection and inflammation of the isthmic portion of the fallopian tube that manifests with wall irregularity and diverticula. SIN is associated with PID and tubal endometriosis, as well as infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Endometriosis is the presence of functioning endometrial tissue outside the uterus and can cause peritubal adhesions.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

More than 1 million cases of PID are treated every year in the United States. Approximately 200,000 women are hospitalized annually for PID. For women aged 16 to 25 years, PID is the most common serious infection. There is an increased risk and incidence for PID in this reproductive age group as a result of the effect of multiple partners, decreased awareness of symptoms, previous episodes of PID, less contraceptive use, and lower socioeconomic status. The increased incidence of PID has paralleled an increase in sexually transmitted diseases. With one episode of PID, the risk for infertility is 8% to 17%, and with three or more episodes of PID, the risk for infertility is up to 75%, although the exact risk varies with the severity of each episode. A history of PID also increase the risk for ectopic pregnancy. TOA, sequela of PID, occurs in approximately 34% of patients initially diagnosed with PID and is also associated with decreased pregnancy rates in approximately 15%.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

PID is an infection of the female genital tract. This typically results from an ascending infection of the vagina or cervix that progresses to endometritis followed by salpingitis and salpingo-oophoritis. The cause is polymicrobial with a prevalence of sexually transmitted organisms, such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae . Other pathogens include gram-negative facultative bacteria, anaerobes, and streptococci. Rarely hematogenous spread occurs. This is usually caused by tuberculosis or direct extension of an adjacent infection or abscess, such as appendicitis or diverticulitis.

Because the infection can spread via the lymph vessels, the condition is usually bilateral. Infection in one fallopian tube usually leads to infection of the other. Adhesions may develop within the fallopian tube, causing tubal obstruction, dilation, and infection. This can lead to hydrosalpinx, in which the distally blocked fallopian tube fills with accumulated intraluminal secretions and becomes markedly dilated. A fallopian tube filled with blood is a hematosalpinx , and when filled with pus is a pyosalpinx . As the infection progresses, peritubal adhesions can form causing adhesion of the fallopian tube with the ovary or other pelvic organs such as the bowel, called the tuboovarian complex . This can further progress into unilateral or bilateral TOAs or rupture, which can result in life-threatening generalized peritonitis.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

The classic symptoms and signs in PID includes lower abdominal pain or pelvic pain, cervical motion and adnexal tenderness, and fever. However, there is a wide variation of symptoms seen in this process, including abnormal smell and color of vaginal discharge, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, nausea and vomiting, and urinary symptoms. Patients with TOA most commonly present with lower abdominal pain and an adnexal mass. Diagnostic criteria that support PID include pelvic or lower abdominal pain, cervical motion/uterine or adnexal tenderness, oral temperature greater than 101° F (>38.3° C), abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge, presence of white blood cells on microscopy of vaginal secretions, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated C-reactive protein, and laboratory documentation of cervical infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis . A low threshold should be used for the diagnosis of PID because the consequences are severe and the presenting symptoms are often atypical.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Ultrasound (US) is the technique most frequently used as the first imaging test in the patient who presents with pelvic pain and fever. Endovaginal US provides detailed examination of the uterus and adnexa, including the fallopian tubes and ovaries. US is an imaging technique most frequently used to confirm a suspected TOA. Computed tomography (CT) is best used as an adjunct to sonography in atypical cases of TOA. Once the infection is treated, assessment of tubal patency is best performed using hysterosalpingography (HSG). When the HSG is abnormal, particularly in the case of peritubal collections, laparoscopy is performed for assessment of the adhesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) aids in noninvasive assessment of tubal dilatation and peritubal disease.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

HSG is the main study in the diagnostic evaluation of the fallopian tubes. This study provides information about tubal morphology and tubal patency. For tubal obstruction, HSG demonstrates no free intraperitoneal spillage of contrast material from the fallopian tubes. Hydrosalpinx is seen as dilatation of the ampullary portions of the fallopian tubes without free intraperitoneal spillage of contrast ( Figure 17-1 ). Abnormal loculated peritubal accumulation of contrast with normal-appearing fallopian tubes is usually seen with peritubal adhesions, such as PID or endometriosis ( Figure 17-2 ). In the latter case, further evaluation should be performed with pelvic MRI. On HSG, tubal irregularity and multiple irregular diverticula along the fallopian tube are seen with SIN ( Figure 17-3 ).

Ultrasound

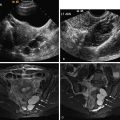

Transvaginal US provides exquisite images of the uterus and adnexa, including the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and any adnexal masses. US is readily available and noninvasive with no ionizing radiation exposure or need for iodinated contrast material. Normal fallopian tubes are not typically identified on US, unless outlined by adjacent free fluid. If the fallopian tubes are identified, they are usually associated with a pathologic process.

Early in PID, the US can appear normal. As the infection progresses, the uterus may become enlarged and ill defined with loss of the normal tissue planes. Thickening of the endometrium with fluid may be present in endometritis. With hydrosalpinx, the fallopian tube becomes fluid filled and dilated with thin or thick echogenic walls. The fallopian tube appears as a fusiform tubular structure extending between the uterus and adnexa with dark anechoic fluid and multiple folds in the tubes ( Figures 17-4 and 17-5 ). In pyosalpinx, US demonstrates a dilated fallopian tube containing complex fluid with echogenic debris (pus) ( Figure 17-6 ). A thickened tubal wall greater than 5 mm usually indicates acute disease. If left untreated, this can progress into a TOA, which appears as a retrouterine or adnexal solid and cystic complex, multiloculated mass with septations, irregular margins, and scattered internal echoes ( Figure 17-7 ). Significant blood flow is identified in most cases of TOAs with color Doppler US. US is useful in assessing the response to treatment and may be used during the percutaneous drainage of a TOA.