15 Assessment of Upper Extremity Arterial Occlusive Disease

The unique structure and function of the upper extremity create challenges for the diagnosis of vascular abnormalities. Unlike the lower extremity, where atherosclerosis or thrombi are almost always the cause of symptomatic disease, upper extremity vascular problems can be more complex. Mechanical compression occurring in the troublesome thoracic outlet region, vasospasm in digital arteries, trauma-related thrombi in the hand and wrist, and embolic thrombi from the heart or from proximal arm aneurysms all must be considered when troubleshooting in the upper extremity. Hand arterial anatomy is confusing and variable and therefore requires a high level of technical expertise. Specialized probes that are capable of resolving small vessels, and displaying flow within them, are required for optimal studies. Finally, physicians and sonographers are generally out of their comfort zone when working in the arm, because arterial disease occurs less commonly in the upper extremity than in the lower extremity. Only about 5% of arterial cases involve the upper extremities.1

This chapter provides the basics of upper extremity arterial assessment, including

1. What to look for clinically

2. What questions to ask before getting started with testing

3. The basic anatomy of the arm and hand arteries that require examination

4. What types of noninvasive tests should be used, and in what order

5. How each examination is performed and interpreted

6. How to know when you have answered the clinical question at hand

Choosing the Right Diagnostic Tool

1. Continuous-wave Doppler (with a recording device to display arterial waveforms)

2. Nonimaging physiologic tests (pulse volume recordings and segmental pressures)

3. Photoplethysmographic (PPG) sensors to detect flow in the digits

4. Color duplex imaging to directly visualize the vessels and the flow within them, and also to identify the type of pathology that is present

One or all of these tools may be needed to diagnose a given problem. For instance, if fingers are cool and discolored with exposure to cold but fine otherwise, the examination will focus on the question of whether this is a vasospastic disorder (for example, Raynaud’s disease) versus a situation in which digital thrombus is present, or a combination of the two. Extensive diagnostic work will have to be done, with close attention to each finger (usually with PPG) and then some kind of cold challenge to provoke symptoms. If cold does not seem to be a factor, the cold challenge may be omitted. If the problem is positional, a baseline PPG study should be done, followed by monitoring of flow in as many different arm positions as possible. Finally, if Doppler and PPG information suggest obstruction, duplex imaging should be done to identify the cause.

Start With the Basics

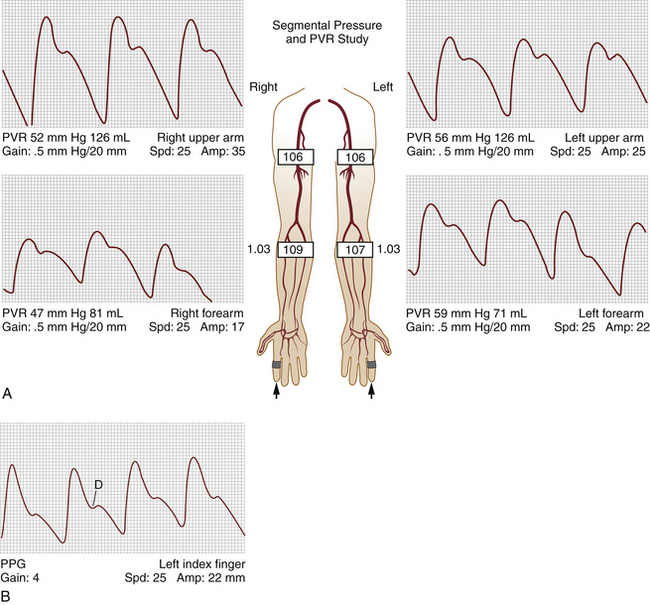

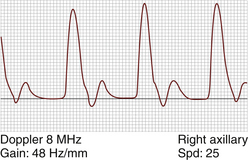

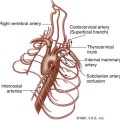

For almost every situation where arterial disease is suspected in the upper extremity, the standard noninvasive starting point is the pulse volume recording (PVR) of arm waveforms, combined with segmental pressure measurements (Figure 15-1). Continuous-wave Doppler signal assessment of the subclavian, axillary, brachial, radial, and ulnar arteries (Figure 15-2) is complementary to the segmental pressures and PVR information. If the fingers are symptomatic, PPGs (see Figure 15-1, B) of all digits should be obtained as well. With this simple group of tests, one can answer the basic clinical question: Is hemodynamically significant arterial obstruction present in a major arm artery?

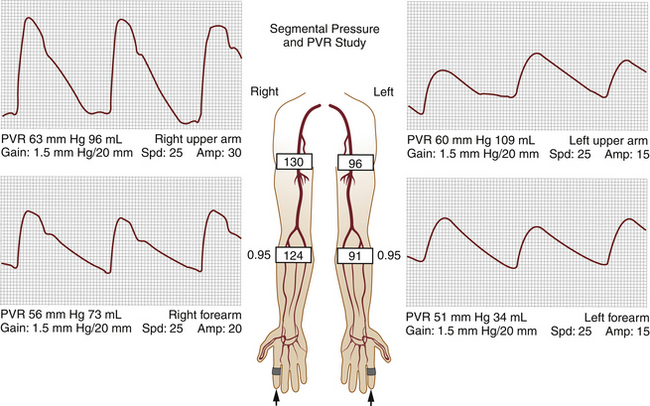

The PVR and Doppler examinations are conducted as follows. Blood pressure cuffs are placed about the midportion of the arm and the forearm, and PVR waveforms are taken at both levels. Then, the systolic blood pressure is measured at both levels, using the audible Doppler signal as an indication of systolic pressure. The measured blood pressures should be similar side to side, as well as from one level to the other (see Figure 15-1, A). A side-to-side blood pressure difference of more than 20 mm Hg or between levels, accompanied by an abnormal PVR (Figure 15-3), may indicate a hemodynamically significant lesion on the side/level with the lower pressure. This finding requires additional testing to determine the cause, usually with direct ultrasound imaging of the vessel(s) in question, as described later in this chapter.

If pressures and waveforms are normal, one can assume there is no hemodynamically significant obstruction in the arteries of the upper extremity. This observation may be an appropriate stopping point, especially if the referring physician only needs to rule out major, limb-threatening disease. It must be understood, however, that normal results of these indirect tests cannot rule out nonobstructive plaque or thrombus, aneurysm, transient mechanical compression of vessels, vasospasm, or other pathologies (such as arteritis). If any of these problems are suspected, additional testing may be required.

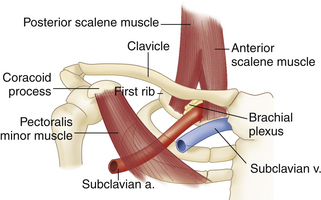

Is There a Problem at the Thoracic Outlet?

When a patient presents with an upper extremity circulatory problem, such as a cold, painful, or numb extremity that varies with limb positioning, a potential cause that should be identified or eliminated from the differential diagnosis early on is mechanical vascular compression at the thoracic outlet. As shown in Figure 15-4, the thoracic outlet is bounded by the clavicle, the first rib, and the scalene muscles. The thoracic outlet syndrome is a common problem, caused by impingement of the subclavian vessels and/or the brachial plexus as they leave the chest. Restriction at the thoracic outlet causes the vessels to be partially or completely compressed when the arm is in certain positions. The repeated vascular irritation over time may injure the artery or vein, leading to intimal damage or thrombus formation. Arterial emboli from thrombus formed in this area may travel distally to other parts of the upper extremity. Therefore, whenever emboli are found, one should consider that they might have originated in the subclavian or axillary arteries.

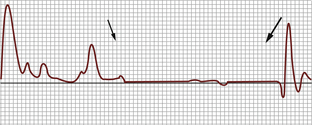

Once a good-quality Doppler signal is acquired at the radial or ulnar artery and the PVR device is adequately registering PVR waveforms, the examiner holding the Doppler probe guides the patient through the arm maneuvers. We usually start with the arm maximally abducted and externally rotated, with the shoulders pulled back as far as possible. The arm is then directed through every conceivable position, while the operators watch the PVR waveform tracing for diminished amplitude or total flattening of the waveform, accompanied by dampening or total loss of the Doppler signal. If a position is identified where such changes occur (Figure 15-5), with recovery of the signals when the arm is moved out of the position, the test is positive and indicates thoracic outlet impingement. This arm position should be repeated, however, and the findings should be the same every time the arm is moved into the obstructing position. Care should be taken to make sure the examiner did not simply move the Doppler probe off the monitored artery during positioning, as this can be a potential source of false-positive results. If the Doppler signal disappears, yet the PVR continues to be robust, recheck the Doppler probe orientation and repeat the maneuver.

Photoplethysmography of Digital Flow Evaluation

After flow in the arms has been checked, attention is next turned to the digits. If there are any problems such as cold, discolored, or painful fingers, arterial flow in the digits should be checked. This is commonly done with PPG sensors that are applied to the pads of the fingers. Double-stick tape is usually used to secure the PPG probe to the fingers. A normal digital PPG waveform has a rapid upstroke, a downstroke that bows toward the baseline, a dicrotic notch, and normal amplitude (see Figure 15-1, B). A person with normal digital arteries may have small, abnormal-looking waveforms if the extremity is cold, so care must be taken to ensure that the examination room is sufficiently warm. If there is any question of the PPG waveforms’ being adversely affected by cold temperature, have the patient warm the hands with a warming blanket before testing. If good-quality, normal waveforms are present in all of the digits, the examination is complete. If the waveforms are blunted, rounded, or absent, additional testing is required.