Chapter 4 Basic Approach to Ultrasound of Other Structures in the Extremities

Cystic or Partially Cystic Soft-Tissue Masses

Simple Cyst

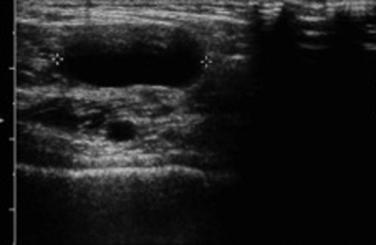

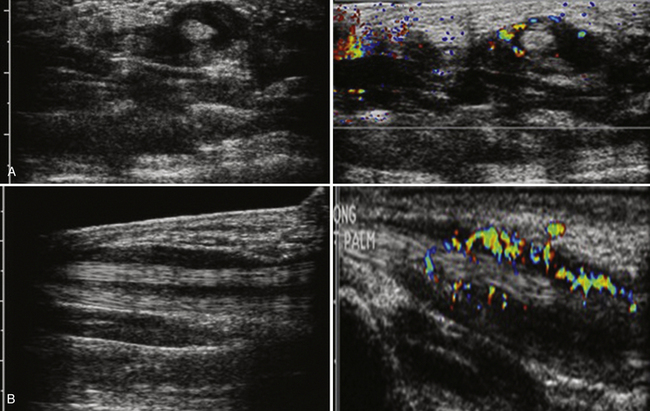

A simple cyst must have all of the following: (1) anechoic, (2) thin or barely perceptible wall, (3) posterior acoustic enhancement, and (4) no evidence of flow on color Doppler evaluation.1 If a mass has all of these features, it can confidently be called benign by the imager. Unfortunately, in the extremities, pure simple cysts are rare (as opposed to within the kidneys or liver, for example). These rules, however, are still applicable and appropriate for describing the features of cystic masses and make a good framework for a report and communication. Expert technique with the use of the appropriate frequency transducer, careful observation and analysis, and documentation of these findings are necessary to prevent errors that might falsely reassure a referring physician or lead to a failure in recognition of significant findings (Fig. 4.1).

Abscess, Cellulitis, and Foreign Body

One of the more unexpected findings for the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer can be an occult abscess. Patients who have these are often referred for limb pain and may have focal tenderness and erythema. Although systemic septicemia can hematogenously seed the soft tissues and set up the necessary components for an abscess, these patients frequently have a history of prior instrumentation (i.e., biopsy or surgery) or trauma at the site of the abscess.2,3 Careful examination to exclude the presence of a foreign body is critical because this can change management. Even without the presence of cellulitis or abscess, the most sensitive method for detection of a foreign body in an extremity is an ultrasound.

In general, foreign bodies should be seen as hyperechoic reflectors. Depending on the composition of the foreign body, this reflector may or may not have posterior acoustic shadowing. Identification of the foreign body and marking its location on the overlying skin can be invaluable to the surgeon in terms of limiting the exposure required for its removal.4 Given the high spatial resolution of ultrasonography, as well as the fact that the majority of foreign bodies are not radiopaque (i.e., wood), ultrasound is the modality of choice the majority of time for imaging small superficial foreign bodies as opposed to fluoroscopy, conventional radiographs, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

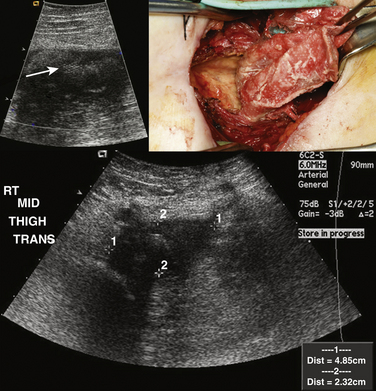

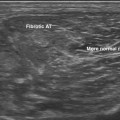

In contrast, an abscess, either with or without associated cellulitis, has a different ultrasonographic appearance. Unlike cellulitis, an abscess is typically well formed, and as a result a discrete measurement of the size and extent can be made. Usually complex in appearance, the typical abscess has a thick wall, which may have increased Doppler flow. Internally, there may be some low level echoes representing complex fluid within the abscess. Again, careful examination is necessary to exclude a foreign body because the presence of a foreign body most often necessitates surgical drainage and removal as opposed to percutaneous drainage alone (Fig. 4.2).2,5–7

Ganglion Cysts

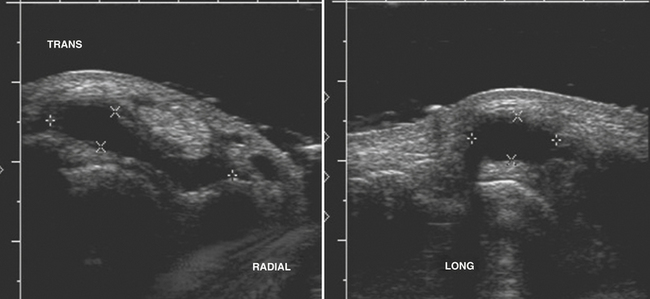

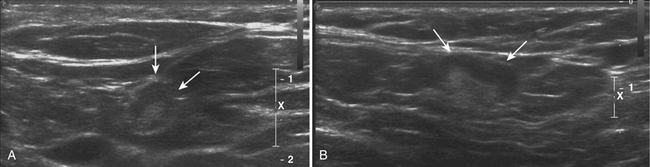

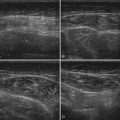

Typically located around the hand and wrist, ganglion cysts are common causes of palpable abnormalities as well as possible generators for extremity pain. The majority arise on the dorsal surface of the hand, with proximity to the scapholunate joint seen in approximately 70% of cases.8 They can also be intimately associated with the flexor tendons of the hand, most commonly around the flexor carpi radialis tendon. Ultrasonographically, these should appear as true cysts, although faint low-level echoes are allowed, given that ganglion cysts may be filled with complex proteinaceous material. Especially in cases in which faint low-level echoes are present, Doppler evaluation is crucial to exclude confusion with a profoundly hypoechoic mass, which is worrisome for a solid soft-tissue mass (Fig. 4.3).9–12

Treatment of these cysts is variable, from observation, to manual rupture, ultrasound-guided steroid injection, and surgery. Unfortunately, given their complex nature, recurrence rates can be quite high and as a result a prior history of treatment of a ganglion cyst should not exclude the diagnosis.13–15

Popliteal (or Baker’s) Cysts

A popliteal, or Baker’s cyst, arises on the posteromedial aspect of the knee within the popliteal fossa. Often a marker for degenerative changes in the knee joint, the popliteal cyst arises between the semimembranosus and medial head of the gastrocnemius.16,17 Patients can present with a palpable mass, swelling, and knee effusion, or they may be asymptomatic.18,19 In addition, given that they have a valve-like mechanism because the cyst neck is trapped between the two muscles, popliteal cysts can wax and wane both in terms of size and degree of symptoms.

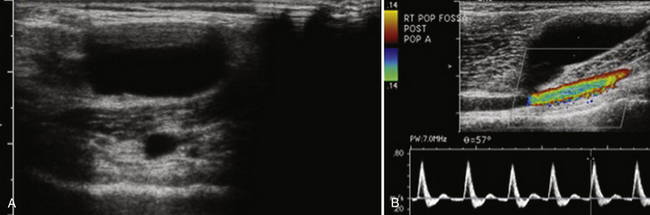

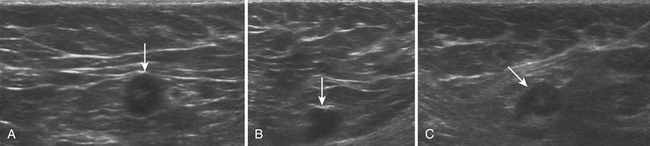

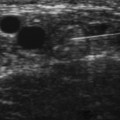

On ultrasound, popliteal cysts are typically purely cystic. The larger they get, the more likely they are to be complex and can even be multiloculated. Internal echoes can be seen, especially in the setting of hemorrhage into the cyst or joint space. Often the neck of the cyst can be identified tapering to dive between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus. Perhaps the most important thing to exclude when imaging a potential popliteal cyst is a popliteal arterial aneurysm. The main way to do this is with color Doppler demonstrating no flow within a popliteal cyst or arterial flow within an aneurysm. This differentiation, obviously, becomes absolutely critical prior to pondering an intervention (Fig. 4.4). In patients with more acute pain with a known popliteal cyst, examination for fluid around and tracking to the cyst can signify recent rupture, which may account for the patient’s symptoms.9,16,19

Treatment includes reassurance and observation, intracystic ultrasound-guided steroid injection, and surgical resection. Unfortunately, as with ganglion cysts in the wrist, recurrence rates regardless of treatment modality are high.19,20

Tenosynovitis

Tenosynovitis is an inflammatory process involving the tendons, either single or multiple, that typically manifests with pain, swelling, and tenderness of the involved tendons.21 Because tenosynovitis can only involve tendons that are encased with synovium, this condition involves primarily the wrists and, to a lesser extent, the ankles. Unfortunately, in some patients the manifesting symptoms can mimic carpal tunnel syndrome and can lead to inappropriate treatment, including surgery.

Although tenosynovitis can manifest acutely and be infectious, most often this condition is due to a chronic inflammatory process. Potential etiologies include chronic inflammatory arthritides such as psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis, overuse injury, and rarely gout. The classic ultrasound picture is that of fluid accumulation with hyperemia within the tendon sheath (Fig. 4.5). The tendon itself is often normal in thickness without hyperemia, which helps distinguish tenosynovitis from tendinosis. MRI is probably more sensitive for the detection of this condition; however, ultrasound can be invaluable in diagnosing tenosynovitis, especially in unsuspected clinical situations such as carpal tunnel syndrome evaluations. Finally, ultrasound is certainly the modality of choice for fluid aspiration for analysis in tenosynovitis.21–23

Joint Effusions

Typically, when evaluating joint effusions, the ultrasonographer examines large joints such as the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle.17,24,25 Although the distribution of the effusion varies depending on the shape of the joint and capsule, some rules for the appearance of the effusions can be made. In general, reactive effusions from associated inflammatory, degenerative, or posttraumatic causes should be relatively anechoic with few, if any, internal echoes. The more complex the appearance with internal echoes the effusion becomes, especially in the acute setting, the more one needs to worry about a potentially septic joint. The septic joint is an orthopedic emergency and needs immediate referral with consideration of ultrasound-guided aspiration for diagnosis. When suspicion is high, especially in deeper joints such as the hip, a lower-frequency transducer should be used to penetrate and better visualize the joint capsule.

Solid Soft-Tissue Masses of the Extremities

Normal Lymph Nodes

The macroscopic structure of a normal lymph node frequently can be seen with ultrasound. The typical structure includes an outer cortex of lymphoid follicles with a central medulla and a hilum composed of follicles, fat, and vessels. When examining a lymph node with ultrasound and trying to determine whether it is normal, trying to identify these two components can be invaluable. Because the central medulla is largely composed of fat, it should be hyperechoic. In addition, with the use of color Doppler, the hilar feeding vessels can be identified. The peripheral cortex gives definition and shape to the normal lymph node. Typically reniform in shape, a normal lymph node’s greatest dimension is often oriented in a craniocaudal direction with the axial dimension being the shortest dimension. The cortex should be relatively symmetric in thickness as well (Fig. 4.6).26

Pathologic Lymph Nodes

The major hallmark of pathology in a lymph node is architectural distortion. Typically this is most readily appreciated in terms of increased size. An absolute number for abnormal size is difficult to provide. Instead, a ratio of long axis to short axis of greater than 1.5 has been suggested as a potential marker for pathology. Especially in cases of suspected neoplastic disease, normal adjacent lymph nodes may be visible (especially in the neck and axilla) that can provide an internal control for what is normal and what is not. Beside overall increased size, another key feature can be asymmetric growth and enlargement of the cortex. Any nodular appearance, especially if it is more hypoechoic, should be looked upon suspiciously. This feature is typically seen in neoplastic processes rather than inflammatory/reactive nodal disease. In abnormal lymph nodes, architectural distortion can also be seen in the central medulla with obliteration of the normal fatty hilum and a loss of the normal hyperechoic appearance. Normal lymph nodes should also not have cystic areas, which will appear as anechoic areas without internal flow on Doppler, or calcifications, which will appear as areas of acoustic shadowing. Both of these features are again suspicious for malignancy with nodal involvement (Fig. 4.7). In general, when faced with a possibly abnormal lymph node, it is probably best to err on the side of describing it and suggesting further workup, short-interval follow-up, or ultrasound-guided biopsy or fine-needle aspiration.27,28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree