In this chapter, benign endometrial causes of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in premenopausal and postmenopausal women will be discussed.

Disease

Definition

AUB in premenopausal women is defined as any bleeding that is unusual for a particular woman, such as heavy menstrual cycles (menorrhagia), irregular menstrual cycles (metrorrhagia), or a combination (menometrorrhagia). In postmenopausal women (either established by hormone testing or lack of a menstrual cycle for 12 consecutive months), any bleeding is considered abnormal.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence rates of AUB, either in premenopausal or postmenopausal women, are difficult to establish. One Dutch survey put the incidence of menorrhagia as 8/1000 women aged 25 to 44 years, per year and 17/1000 women aged 25 to 44 years, per year for irregular bleeding, including intermenstrual bleeding. Another study estimated the prevalence of AUB in premenopausal women as somewhere between 9% and 30%. One survey of 257 Danish postmenopausal women aged less than 74 years found a prevalence of AUB of 15% and among 429 premenopausal women aged more than 20 years, a prevalence of AUB of 46%. This last publication may overestimate the prevalence if one assumes symptomatic women may be more likely to participate in such a survey study. What is known is that during a lifetime, many women will seek the care of a physician for AUB and that many procedures, interventions, tests, and surgeries are performed on such women.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The main benign causes of AUB vary in frequency between premenopausal and postmenopausal women but include endometrial atrophy (postmenopausal only), hyperplasia, polyps, and tamoxifen use.

Atrophy of the endometrium is assumed to be the cause of postmenopausal bleeding when the endometrium measures 4 mm or less by transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS). In one study of 1168 women, if the endometrium measured 4 mm or less, an abnormal biopsy was reported in only 4%, and none were cancer. The average endometrial thickness was 3.9 mm in atrophy versus 21.1 mm in cancer.

Endometrial hyperplasia is thought to be related to an excess of unopposed estrogens as may be seen with anovulatory cycles in premenopausal women and exogenous use in postmenopausal women; excess estrogen has also been shown to increase the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma. Endometrial polyps are also thought to be related to an excess of unopposed estrogen in postmenopausal women because certain hormone replacement regimens have been implicated in their formation. In premenopausal women, obesity has also been implicated as a risk factor.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation in premenopausal women varies from heavy cycles (menorrhagia) to irregular cycles, including bleeding between cycles (metrorrhagia) and a combination of the two (menometrorrhagia). In postmenopausal women, any bleeding, from spotting to episodes reminiscent of a menstrual cycle, is considered abnormal.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

In premenopausal women, especially those in whom hormonal causes of abnormal bleeding are excluded, imaging with pelvic ultrasound (US) is indicated as a first-line test to detect the presence of structural abnormalities that may cause bleeding. US is best performed as soon after a menstrual cycle as possible.

In postmenopausal women, an endometrial biopsy may be the first test performed; if a malignancy is found, imaging for staging may be indicated, but not for diagnostic purposes. If the biopsy is inconclusive, TVUS is the next step. If the endometrium is uniformly thin (≤4 mm), malignancy is virtually excluded, and unless bleeding recurs or persists, no further tests are necessary. Cancer risk is 7.3% if the endometrium is greater than 5 mm. Therefore when the endometrium measures 5 mm or more, additional testing is required. If the biopsy suggests the presence of polyps, hysterosonography may be preferred over routine TVUS as the next step.

Some clinicians may prefer US as the first test in a postmenopausal woman with bleeding. If the endometrium is uniformly thin (≤4 mm), malignancy is virtually excluded, and unless bleeding recurs or persists, no further tests are needed. If a diffuse process is suggested, the patient may go on to endometrial sampling. If a focal process is suggested, the patient may undergo hysterosonography to help detect any focal abnormality and guide hysteroscopy. Alternatively the clinician may elect to immediately perform hysteroscopy and biopsy.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

No indications exist at present for radiography in the diagnosis of AUB.

Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound (TAUS) of the pelvis through a full bladder may be the first imaging examination performed in women referred for AUB. TAUS is particularly good for measuring the overall size of the uterus and suggesting the presence of uterine leiomyomas.

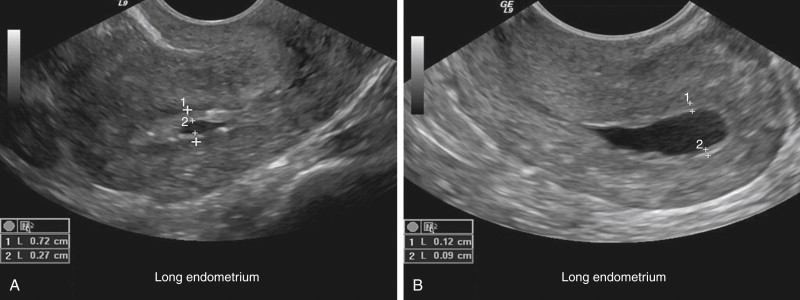

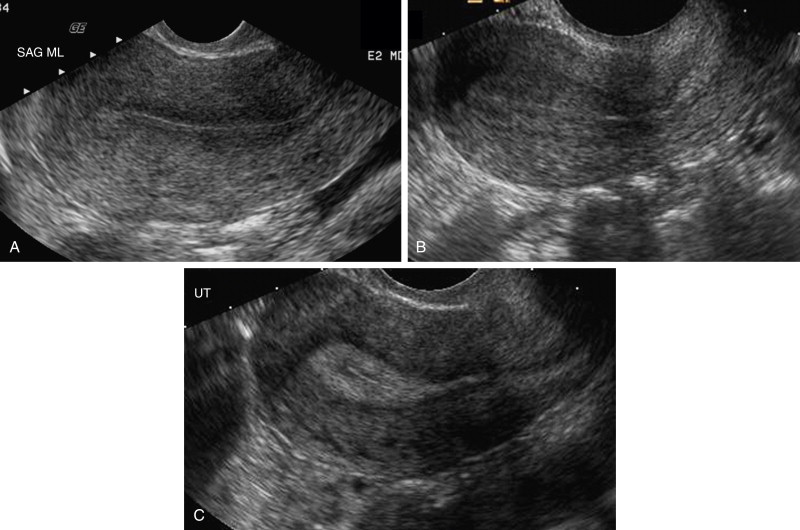

Transvaginal ultrasound is preferred for obtaining a more accurate measurement of endometrial thickness, assessment of endometrial echotexture, and for detection of any endometrial irregularity. The endometrium should be measured on a long axis (sagittal) image of the uterus at its thickest point ( Figure 13-1 ). If fluid is present within the endometrial canal, the entire endometrial thickness including the fluid is measured, and the thickness of the fluid is subtracted or the two sides of the endometrium are measured separately and added ( Figure 13-2 ). In premenopausal women, the normal endometrial thickness and echotexture vary with the menstrual cycle ( Figure 13-3 ). During menses the endometrium is thin, and fluid may be present in the endometrial cavity. During the follicular phase, the endometrium is hypoechoic and thin; during the secretory phase, it becomes thicker and more echogenic. Timing of scanning during the first week after menses may allow more optimal detection of endometrial pathology such as polyps because polyps tend to be echogenic and will be more easily visualized against the background of a thin hypoechoic endometrium ( Figure 13-4 ). In postmenopausal women the endometrium should be uniform, thin, and echogenic, measuring 5 mm or less. A small amount of fluid may be present and may indicate cervical stenosis but not endometrial pathology ( Figure 13-5 ).

Color Doppler imaging should be added whenever endometrial pathology is suspected.

Atrophy presents as a uniform, thin, echogenic endometrium generally measuring less than 4 mm on TVUS ( Figure 13-6 ). Hyperplasia may be a focal or diffuse process manifesting as echogenic thickening with or without small intrinsic cystic spaces ( Figure 13-7 ). Polyps may be sessile or pedunculated and, in up to 20% of cases, multiple. They present as focal, homogeneous hyperechoic masses that may have small cystic spaces; if no fluid is present in the endometrial canal, polyps may mimic hyperplasia ( Figure 13-8 ). Doppler imaging should be added to assess for a feeding vessel or vascular stalk, which also helps indicate from which wall of the uterus the polyp arises ( Figure 13-9 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree