Sue J. Barter, Fleur Kilburn-Toppin

Benign Gynaecological Disease

This chapter gives a brief review of common benign gynaecological disorders and presents indications for the role of ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in investigation, problem solving and management.

Imaging Techniques

Ultrasound

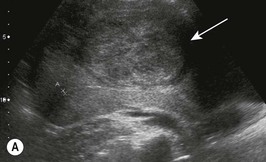

Ultrasound (transabdominal and transvaginal) is accepted as the primary imaging technique for examining the female pelvis. Indications include evaluation of a suspected pelvic mass, acute pelvic pain, causes of uterine enlargement, investigation of postmenopausal bleeding and characterisation of ovarian masses, as well as guiding invasive procedures such as biopsy and drainage.

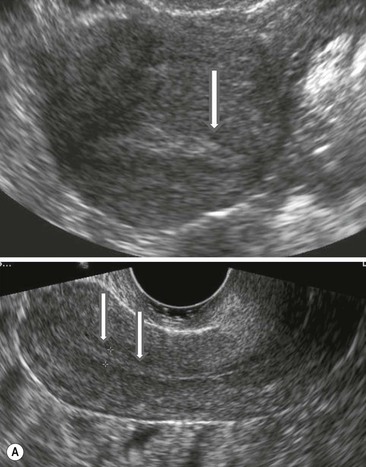

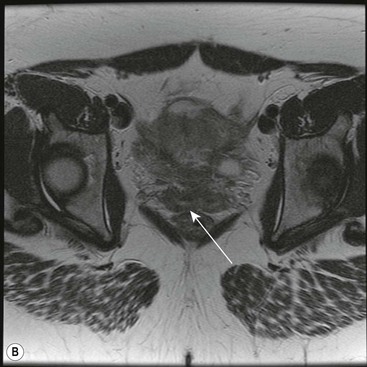

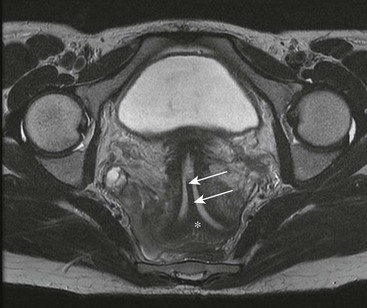

Ultrasound has many advantages in routine pelvic imaging: it is relatively inexpensive, provides multiplanar views, is widely available and lacks ionising radiation or contrast media (Fig. 42-1).

Computed Tomography

The role of CT in benign gynaecological conditions has largely been replaced by MRI, although it may be used to investigate acute pelvic pain where US has been unhelpful (Fig. 42-2).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

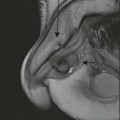

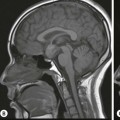

The role of MRI in gynaecology has evolved rapidly, and it is now commonly used for the investigation of Müllerian duct anomalies and benign conditions such as endometriosis and evaluation of fibroids especially before possible embolisation. It is invaluable in investigation of the indeterminate adnexal mass (Fig. 42-3).

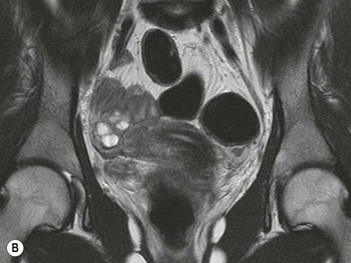

Hysterosalpingography and Fallopian Tube Catheterisation

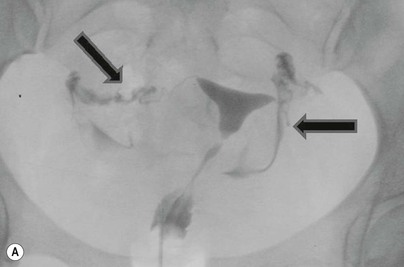

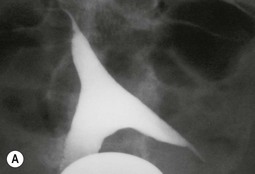

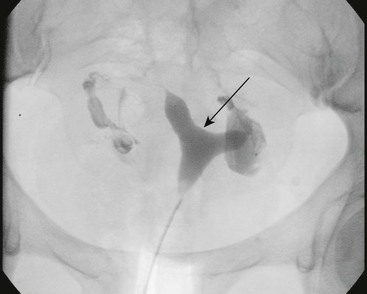

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is used mainly to investigate infertility. It is best performed in the first 10 days of the cycle, but not during active bleeding. Contraindications are pregnancy and active pelvic infection. Complications include pain, pelvic infection, haemorrhage and vasovagal attacks (Fig. 42-4).

Fallopian tube catheterisation is a technique using small catheters and guidewires to cannulate the fallopian tubes and establish patency if there is cornual occlusion in an otherwise normal pelvis. Pregnancy rates of around 60% have been reported following the procedure1 (Fig. 42-5).

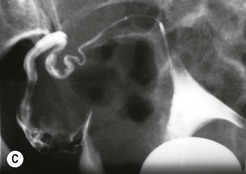

Sonohysterography

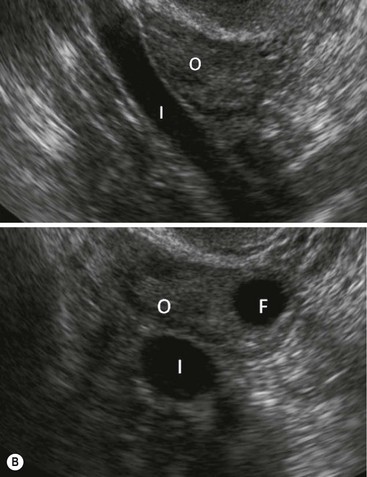

This technique involves placement of a 5F balloon catheter through the cervix and instilling sterile saline or a microbubble solution under direct ultrasound visualisation (Fig. 42-6). The procedure is well tolerated, with contraindications and complications similar to HSG.

It is indicated for evaluation of masses detected in the uterine cavity at US, and fallopian tube patency. Some fertility centres prefer HSG because of the additional information obtained despite the radiation dose.

Congenital Anomalies of the Female Genital Tract

Congenital uterine anomalies comprise a wide spectrum of disorders, occurring in 1–15% of women. Embryologically, they result from abnormal development and fusion of the paired Müllerian ducts from which the uterus, the upper two-thirds of the vagina and the fallopian tubes are derived. They are associated with menstrual disorders, infertility and obstetric complications, and a high incidence of renal anomalies, particularly agenesis and ectopia. Often, more minor Müllerian duct abnormalities are detected incidentally during investigations for other conditions.

MRI, which provides exquisite detail of pelvic anatomy, is the most accurate imaging technique for investigating and classifying congenital anomalies; classification is important as fertility outcomes and surgical management vary considerably. In addition to standard MR imaging planes, coronal oblique planes (parallel to the long axis of the uterus) and axial oblique planes (perpendicular to the long axis of the uterus) should be obtained for optimal imaging to allow for variation in uterine flexion.2 T2-weighted images are best for uterine zonal anatomy, whereas coronal oblique T1-weighted images best depict the fundal contour. A standard coronal T1-weighted image through the kidneys is important due to the high association of renal abnormalities.

Müllerian Duct Anomalies

These disorders are classified according to Buttram and Gibbons and the American Fertility Society.3

Class I: Uterine Agenesis or Hypoplasia

Uterine agenesis or hypoplasia results from failure of normal development of both Müllerian ducts. The ovaries are normal most patients, helping to distinguish the condition from other syndromes such as androgen insensitivity and gonadal dysgenesis.4

The commonest subtype of uterine agenesis is the Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. There is uterine and vaginal agenesis or hypoplasia with intact ovaries and fallopian tubes with variable anomalies of the urinary tract and skeletal system.

Detection of uterine remnants may be difficult on US and sagittal and axial MR images can more reliably detect the absence or anomalies of the uterus and vagina, respectively5 (Fig. 42-7).

Class II: Unicornuate Uterus

This results from failure of normal development of one Müllerian duct, and is associated with increased spontaneous abortion and obstetric complications, and renal abnormalities.

On T2-weighted MR images, the unicornuate uterus demonstrates a curved, elongated uterus with tapering of the fundal segment off midline (the ‘banana-like’ configuration) best seen on the axial oblique (long axis) images (Fig. 42-8).

Normal uterine zonal anatomy is maintained. If a rudimentary horn is present, it usually demonstrates lower signal intensity.

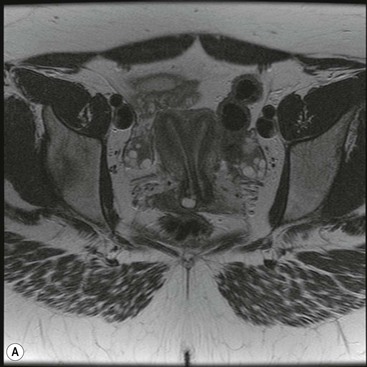

Class III: Uterus Didelphys

Non-fusion of the Müllerian ducts results in uterus didelphys with two separate normal-sized uterine horns and cervices. A longitudinal vaginal septum is present in 75% of cases. On coronal oblique T2-weighted images the two uterine horns can be appreciated, which are usually widely separated with preservation of the endometrial and myometrial widths (Fig. 42-9).

Class IV: Bicornuate Uterus

Incomplete fusion of the cephalad extent of the uterovaginal horns with resorption of the uterovaginal septum gives rise to a bicornuate uterus. Obstetric complications relate to the degree of non-fusion of the horns. T2-weighted coronal images show the communicating uterine horns with a concave fundus. They are separated by an intervening cleft longer than 1 cm in the external fundal myometrium, which demonstrates signal intensity the same as that of myometrium on all sequences. Normal zonal anatomy is seen in each horn (Fig. 42-10).

Class V: Septate Uterus

This is the commonest Müllerian duct abnormality, with incomplete resorption of the fibrous septum between the two uterine horns. The septum may be partial or complete, extending to the external cervical os. The differentiation between the septate and the bicornuate uterus is clinically important because the septate uterus has the worst obstetric outcome of all Müllerian duct abnormalities. The fibrous septum is best demonstrated on coronal oblique T2-weighted MR images, with the key differentiating factor being the external uterine contour, which is convex, flat or concave (<1 cm) in contrast to the bicornuate uterus6 (Fig. 42-11).

Class VI: Arcuate Uterus

This is considered a normal variant, and is thought to have no significant effects on fertility or pregnancy. On imaging there is a smooth, broad indentation of the fundus of the uterine cavity, with a normal external uterine contour (Fig. 42-12).

Class VII: Diethylstilbestrol Related

Diethylstilbestrol is a synthetic oestrogen which can produce uterine abnormalities secondary to in utero exposure. A T-shaped uterine cavity is the commonest finding, with uterine hypoplasia, irregular constrictions and intraluminal filling defects also seen.

Vaginal Anomalies

Defects in vertical and lateral fusion of the Müllerian ducts can result in vaginal septae formation. Along with vaginal agenesis, as seen in MRKH syndrome, these may cause obstruction, preventing loss of menstrual blood and leading to haematocolpos or haematometrocolpos.

On MRI, the septum is identified as low signal intensity fibrous tissue on T2-weighted sagittal images, with loss of vaginal zonal anatomy (Fig. 42-9B). Dilatation of the vagina with intraluminal fluid of intermediate or high signal intensity and the occasional presence of fluid/debris levels can also be shown. T1-weighted images with fat suppression confirm blood products in haematometrocolpos.

Imaging of Ambiguous Genitalia

This is a broad spectrum of disorders, including male (46 XY) and female (46 XX) pseudo and true hermaphroditism and gonadal dysgenesis, including Turner’s syndrome. Imaging is important for depicting internal genitalia and identifying gonads. US is the initial imaging investigation of choice, but MR is often used as a problem-solving tool. Streak ovaries, as seen in Turner’s syndrome, are particularly difficult to detect and appear as low signal stripes on T2-weighted MR. Additional high signal intensity foci should raise the suspicion of malignant change.7

Benign Uterine Conditions

Fibroids

Fibroids, or leiomyomas, are benign smooth muscle tumours found in up to 40% of women. They are usually multiple and are classified according to their location:

• Submucosal (projecting into and distorting the uterine cavity);

• Intramural (within the myometrium); and

• Subserosal (protruding out of the serosal surface of the uterus).

Symptoms may be caused by mass effect and location of the fibroids, and include menorrhagia, pain, urinary symptoms, infertility and obstetric complications.

Alternative procedures to hysterectomy such as myomectomy, uterine arterial embolisation (UAE) and MR-guided high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation may be appropriate for some patients wishing to preserve fertility.8,9

Ultrasound is often the initial radiological investigation in these patients, with MRI reserved for patients with inconclusive US results or for patient selection and pre-treatment planning before myomectomy and UAE.10

Ultrasound

US can accurately detect fibroids, but up to 20% of small fibroids may be occult. The fibroid uterus is typically enlarged with an irregular or lobulated outline. Fibroids commonly appear as well-marginated, hypoechoic, rounded or oval masses within the uterine body. Depending on the proportion of smooth muscle, fibrosis and degeneration, the appearance ranges from hypoechoic to echogenic, homogeneous to heterogeneous, with or without acoustic shadowing. Calcification secondary to necrosis or degeneration appears as shadowing echogenic foci (Fig. 42-13).

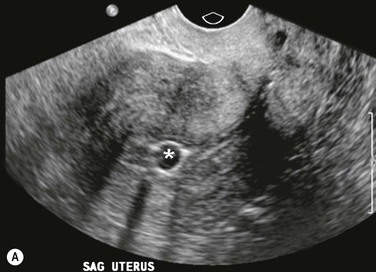

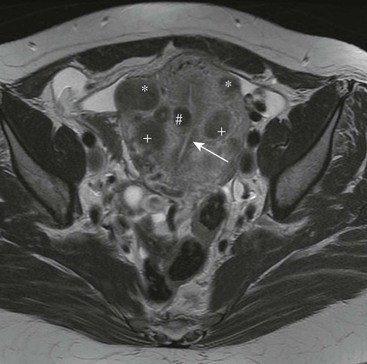

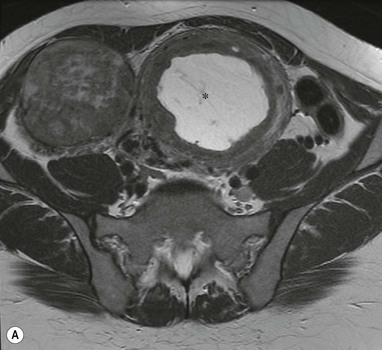

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI allows precise determination of the size, location and number of fibroids, and is useful in evaluation and monitoring response in patients undergoing myomectomy and UAE. It is the most accurate non-invasive imaging method for differentiation of a fibroid from adenomyosis.11

The commonest appearances are of well-circumscribed, rounded masses with lower signal intensity than myometrium on T2-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 42-14). Most enhance less than adjacent myometrium following contrast; however, a variety of degenerative processes can alter the characteristic appearances, making differential diagnosis more difficult.12 Cystic degeneration results in well-demarcated areas with fluid signal intensity, which do not enhance post-IV contrast medium (Fig. 42-15). Myxoid degeneration may show very high signal on T2-weighted images with minimal enhancement. Red degeneration involves massive haemorrhagic infarction and necrosis of the entire fibroid, with a peripheral rim of low signal on T2- and high signal on T1-weighted images, with no enhancement (Fig. 42-16). Fat saturation T1-weighted images may be helpful in cases of haemorrhage. Calcification usually results in areas of signal void on both T1- and T2-weighted images.

Computed Tomography

CT is not used for routine evaluation of fibroids. They are often an incidental finding on CT performed for other reasons, and usually have a soft-tissue density similar to that of normal myometrium, although necrosis or degeneration may result in low attenuation. Contour deformity is the most common sign on CT; calcification is the most specific finding.

Hysterosalpingography

HSG is no longer recommended for the evaluation of submucosal fibroids, although distortion of the cavity may been seen at HSG performed for investigation of infertility. Appearances range from a smooth and rounded filling defect of the uterine contour, to gross distortion of the cavity.

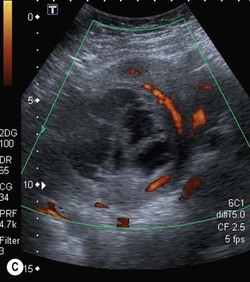

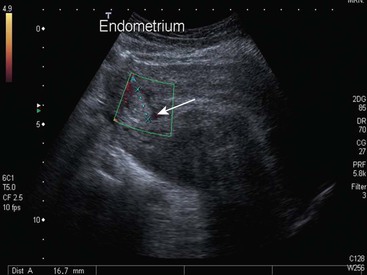

Endometrial Polyps

Benign endometrial polyps commonly occur at all ages, with their greatest prevalence after age 50. They are a common cause of postmenopausal bleeding and are often seen in patients taking tamoxifen. They must be differentiated from submucosal fibroids and malignancy. Polyps are well seen on sonohysterography. They are typically homogeneous, isoechoic to and continuous with the endometrium and preserve the endomyometrial interface. They may be centrally cystic, corresponding to dilated, fluid-filled glands. Colour Doppler may reveal a characteristic feeding vessel (Fig. 42-17).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree